JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2022 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY || Benedictinism Website To reproduce

Amherst Manuscript, Add. 37,790, fols. 97-97v, apply to The

British Library, The Picture Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1

2DB.

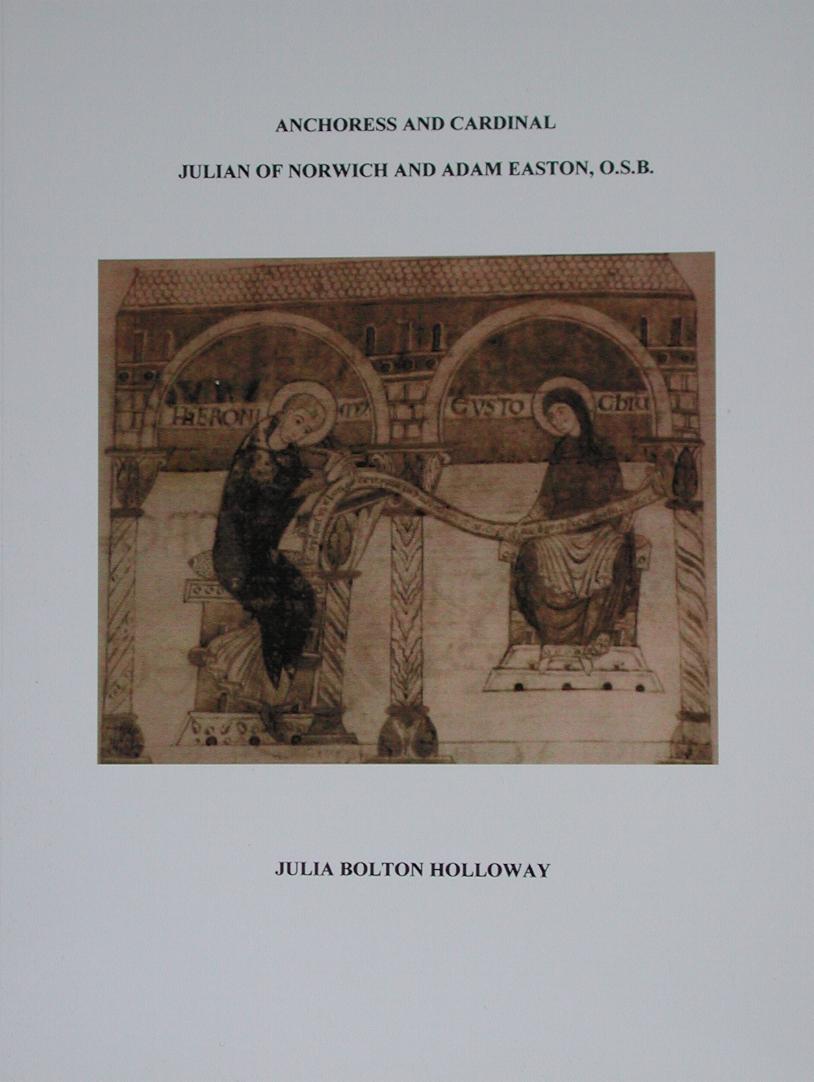

ANCHORESS AND CARDINAL:

JULIAN OF NORWICH AND ADAM

EASTON O.S.B.

LECTURE, NORWICH CATHEDRAL,

1 DECEMBER 1998

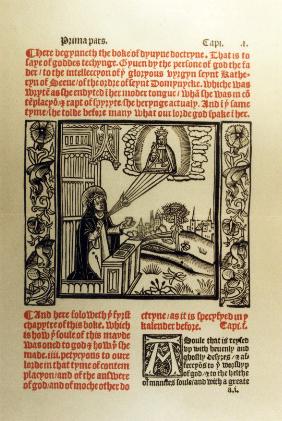

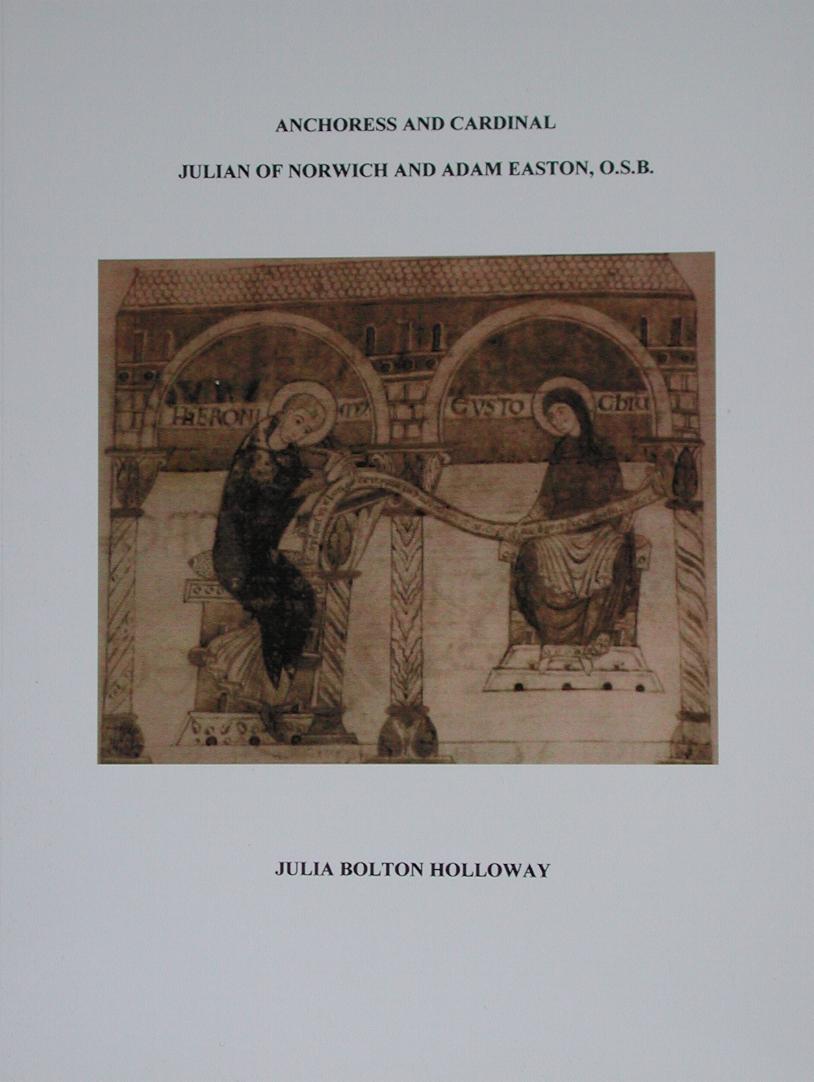

St Birgitta presents her Revelationes to

Christendom, the Cardinal at her right, Adam Easton, O.S.B.,

of Norwich. From the editio princeps, Lubeck: Ghotan,

1492.

Birgitta of Sweden, Revelationes , Lübeck:

Ghotan, 1492

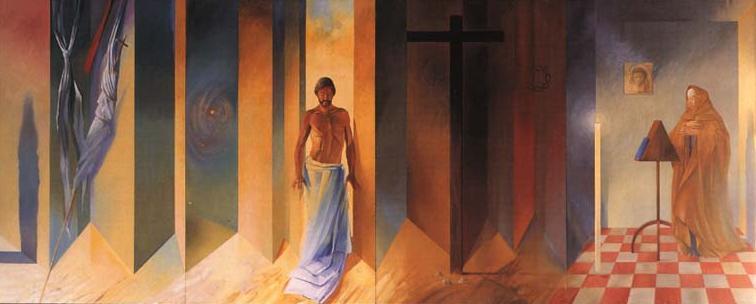

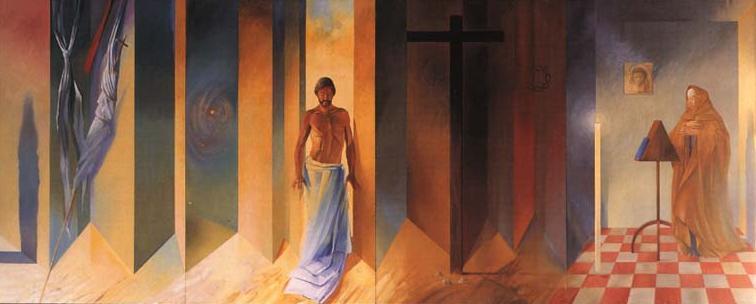

HEN I last visited Norwich /* Alan Oldfield, 'Revelations of Divine

Love', owned by Friends of Julian of Norwich, in St

Gabriel's Chapel, All Hallows Convent, Ditchingham, Suffolk.

Rubricated footnotes with * (doubled for two images),

describe the slides used in 1 December 1998 Lecture, Norwich

Cathedral./ vergers were

telling me of the exhibition held in this Cathedral of vast

canvases painted by an Australian painter, Alan Oldfield.

They thought it very strange that an Australian from far

away and down under would be painting such huge pictures

about a mere Norwich girl. Here we see an aged Julian the

Anchoress in her cell before her lectern, a cross, a

veronica veil - and then through the aperture comes the

young handsome Christ in Mary's

blue , in Aaron's blue ,

while beyond the whole cosmos wheels away. Julian is of all

time and all space.

HEN I last visited Norwich /* Alan Oldfield, 'Revelations of Divine

Love', owned by Friends of Julian of Norwich, in St

Gabriel's Chapel, All Hallows Convent, Ditchingham, Suffolk.

Rubricated footnotes with * (doubled for two images),

describe the slides used in 1 December 1998 Lecture, Norwich

Cathedral./ vergers were

telling me of the exhibition held in this Cathedral of vast

canvases painted by an Australian painter, Alan Oldfield.

They thought it very strange that an Australian from far

away and down under would be painting such huge pictures

about a mere Norwich girl. Here we see an aged Julian the

Anchoress in her cell before her lectern, a cross, a

veronica veil - and then through the aperture comes the

young handsome Christ in Mary's

blue , in Aaron's blue ,

while beyond the whole cosmos wheels away. Julian is of all

time and all space.

Alan Oldfield, 'The Revelations of Julian of

Norwich', Friends of Julian of Norwich, St Gabriel's Chapel,

Community of All Hallows, Ditchingham, Bungay, Suffolk.

This paper will discuss our anchoress, Julian of

Norwich; a lawyer's daughter, Birgitta of Sweden ;

a dyer's daughter, Catherine

of Siena ; a mayor's daughter, Margery

Kempe of Lynn; and a cardinal, Adam

Easton , O.S.B., who may have linked them all together

in a pan-European textual community, of women, literate and

illiterate, who wrote visionary books./1

/1.The term 'textual community' used by Brian

Stock, Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models

of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983); it works equally

well for the theological writings of the fourteenth-century

Friends of God movement by women and men, some of whose texts

are in the Amherst Manuscript with Julian's earliest surviving Showing,

British Library, Add. 37,790./

There are four manuscript versions of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love

,/2

/2. Westminster Cathedral , MS Treasury 4

(siglum W), on loan to Westminster Abbey; Paris , Bibliothèque Nationale,

MS anglais 40 (siglum P); British Library, Sloane 2499 (siglum S1);

British Library, Amherst , MS

Add. 37,790 (siglum A). Sigla established by Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds, C.P., University of Leeds, M.A. Thesis, 1947.

Citations in this paper will be by siglum and folio, e.g.

P141v./

further copies of two of these,/3

/3. Sloane 3705 (siglum S2),

actually copies an exemplar rather than S1; Stowe 42 (siglum C1), copies

exemplar to P or fair copy to Serenus Cressy's 1670 editio

princeps. SS are shorter versions of the Long Text, but

with added chapter descriptions; P,C1 and the Serenus Cressy

1670 editio princeps are a longer version of the Long

Text without chapter descriptions./

two manuscript fragments,/4

one report of a conversation held with her,/5

/5. The

Book of Margery Kempe ,

British Library, Add. 61,823 (siglum M), M21-21v; ed. Sanford

Brown Meech and Hope Emily Allen, Early English Text Society

(EETS) 212.42-43./

and four wills naming her. None of these are written

in her own hand. There are no editions in print today that

faithfully render what we have of Julian's Showing.

There may however be a

manuscript that is written by her, in her own hand, though

it is not Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love. It is

in Norwich Castle and is a

collection of texts written by an anchoress for anchoresses.

It is beautiful, beginning with a lovely Gothic letter  in gold leaf on a

purple ground./6

in gold leaf on a

purple ground./6

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 1

/6.

Norwich Castle Museum, MS 158.926 4g.5, Theological Treatises in

English. The use of gold on purple reflects imperial codices,

adopted in Christianity for Bibles, and noted by St Boniface as having been

particularly the production of English nuns./

St Birgitta at Prayer, Revelationes ,

Lübeck: Ghotan, 1492

In the work of editing the Julian manuscripts,

published by SISMEL in 2001, I encountered difficulties in

dating the versions of her text. In 1990 I asked Westminster Cathedral if I could

see their manuscript. the following year, after an awkward

silence, for it had been safely placed in a safe and its

whereabouts forgotten, then found again, I was told I could

come back and edit it./7

/7.

Translated, Betty Foucard, 1955; edited, Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds, C.P., Leeds University Doctor of Philosophy Thesis,

1956, Appendix B; Julia Bolton Holloway in Edward P. Nolan, Cry

Out and Write: A Feminine Poetics of Revelation (New York:

Continuum, 1994), pp. 139-203; Hugh Kempster, Mystics

Quarterly 23 (1997); it may have returned to England from

Lisbon's Syon Abbey in the nineteenth century./

The manuscript begins with the date '1368', though

it is copied out later than that.

Westminster Cathedral Manuscript, date of '1368',

bottom first folio.

It is the second-oldest manuscript we have of

Julian's Showing. It has no reference to the death-bed

vision of 1373. In it Julian speaks of her desire to die when

young, and God tells her this will happen soon. Julian in 1368

was just 25 years old. Yet the theology of this manuscript is

brilliant. It opens with the Great O Antiphon, of '{ OUre gracious god

', as Wisdom and

Truth, it shows the Nativity of the Word, surrealistically

going backwards in time, becoming the Annunciation, the Word

within Mary's Soul, like the book within Julian's and our

hands. The Long Text refers back to this scene as its First

Showing (P8-9,10v, 11-11v,13v-14,47v-48v,128v), which it is

not there. It next includes the hazel nut passage, and it

quotes again and again from St Gregory's Dialogues

on the Life of St Benedict

, on how when the soul sees the Creator all that is created

seems little. Then it turns that inside out, like the

Beatles' pocket, and speaks of God in a point, from Pseudo-Dionysius ,

the Greek Church Father, and from Boethius , the Latin

Church Father. It discourses upon prayer, using Origen and

William of St Thierry's Golden Epistle. It talks to

us of Jesus as Mother

, partly from John Whiterig's Meditationes,/8

/8.

John Whiterig, 'The Meditations of the Monk of Farne', ed. Hugh

Farmer, Studia Anselmiana 41 (1957); The Monk of

Farne: The Meditations of a Fourteenth-Century Monk, ed.,

Dom Hugh Farmer, O.S.B., trans., a Benedictine of Stanbrook

(Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1961), p. 64./

reflecting back to that opening of God and

Mary being 'oned ' in the Great O Antiphon of Wisdom , rather than the

noughting of this world. Throughout is the theme of Wisdom and

Truth and the discoursing upon prayer. Julian uses the

concept, from Pseudo-Dionysius, Marguerite Porete and Dante

Alighieri, of the Holy Trinity, to which this Cathedral is

dedicated, having the attributes of Might, Wisdom and Love. I

dedicate this talk to God as Almighty, as all Wisdom and as

all Love.

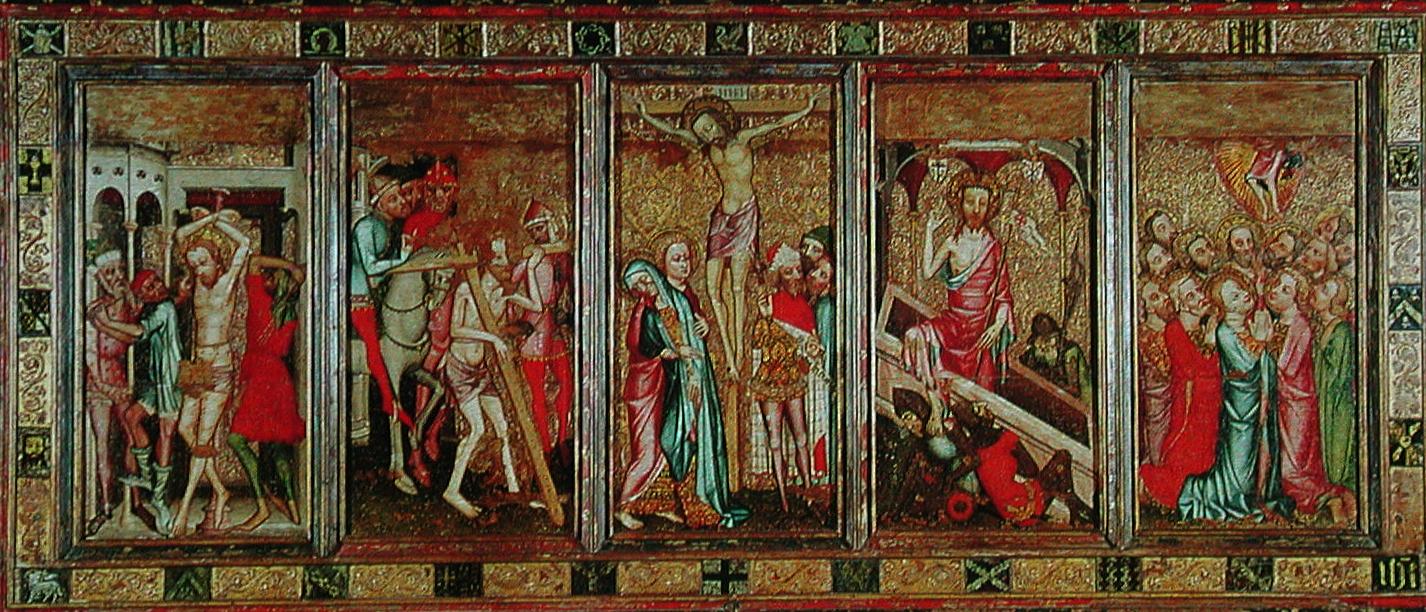

The Long Text version of Julian's Showing

is copied out abroad, first by Syon Brigittine nuns in exile,

then by Cambrai Benedictine English nuns in exile, in four

manuscripts and was first printed in 1670. This version is

structured as XV+I Showings (lacking as such in W and A) based

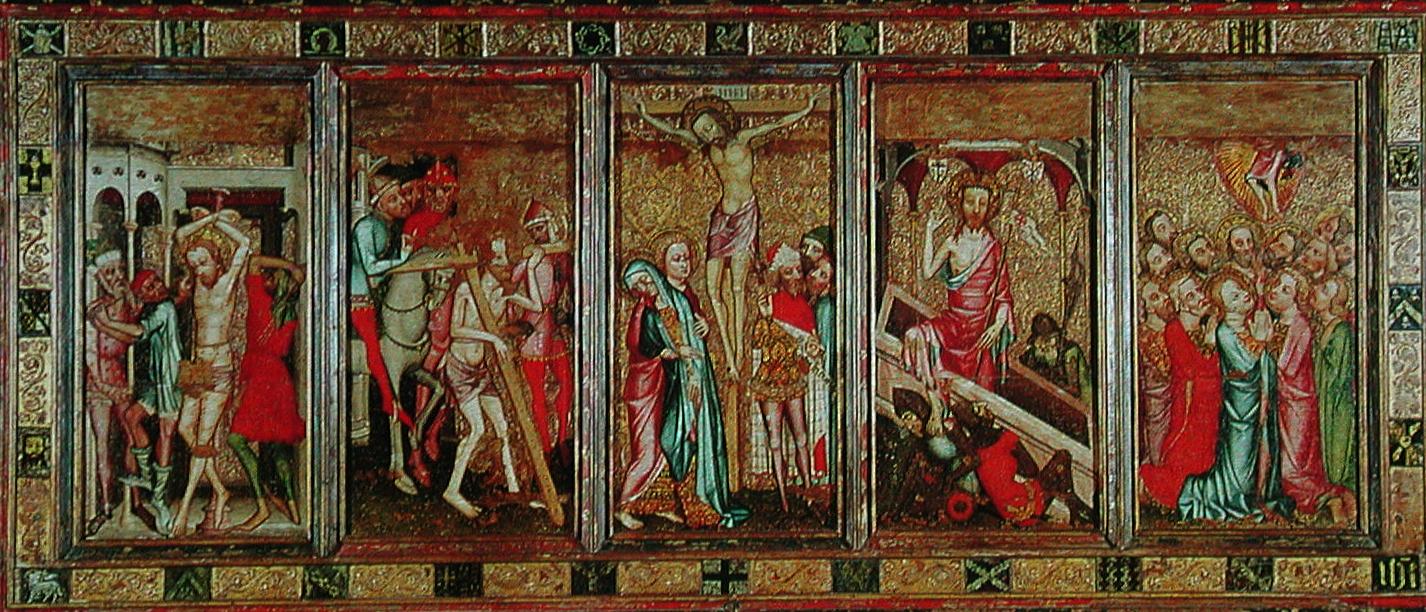

upon the Crucifix and its bleeding that Julian saw when it was

held before her as she and those with her thought she lay

dying. Julian says within this version of her text that she

wrote it 15-20 years minus three months after that 'death-bed'

vision at 30 and a half, on 13 May 1373, thus writing it when

she was 45-50, from 1388-February 1393. This version includes

the Lord and the Servant Parable. What I especially like about

this Long Text is that in the Brigittine Paris Manuscript Christ's words to

Julian are given by the scribe in

red , like a Red Letter Bible

. We hoped to publish our edition of the manuscripts

replicating those pages that way for you. Failing that, at

least the paperback translation of the manuscripts.

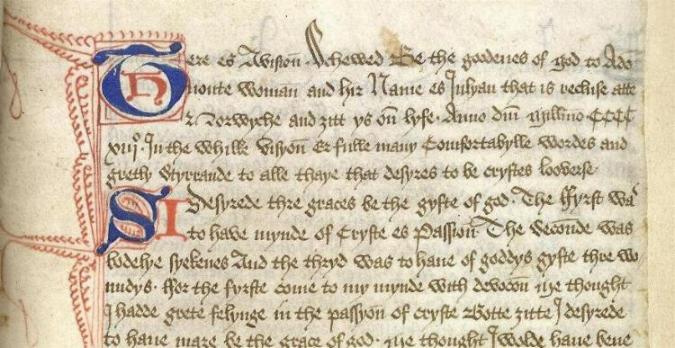

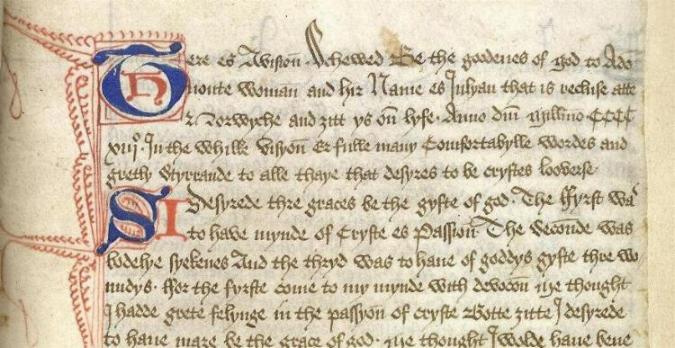

The Short Text of the circa

1435-50 Amherst Manuscript of

the Showing says that its one vision, 'Avisioun,'

was shown to 'Julyan that is

recluse atte Norwyche and 3ett ys oun lyf', and thus 70, its text being written out

in 1413.

{

ere es Avisioun. Shewed Be the goodenes of

god to Ade=

ere es Avisioun. Shewed Be the goodenes of

god to Ade=

uoute woman and hir Name es

Julyan that is recluse atte

Norwyche and 3itt ys oun

lufe. Anno domini millesimo CCCC

xiij [1413]. In the whilke

visyou n er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and

and gretly Styrande to all they

that desyres to be crystes looveres.

By Permission of the British Library, Amherst

Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97.

This Showing of Love manuscript version

Julian scholars currently believe was written soon after the

'deathbed' vision of 1373, almost forty years earlier than

1413. But Nicholas Watson, in Canada, has been finding that it

reflects the greater anxiety typical of that later period,

when Chancellor Archbishop Arundel

, countering John Wyclif's Lollard Movement, was prohibiting

lay people from teaching theology, especially women, and from

their using the Bible in the English language./9

/9.

Nicholas Watson, 'The Composition of Julian of Norwich's Revelation

of Love', Speculum 68 (1993), 637-683; 'Censorship

and Cultural Change in Late-Medieval England: Vernacular

Theology, the Oxford Translation Debate, and Arundel's

Constitutions of 1409', Speculum 70 (1995), 822-864. He

argues as do others that Julian's Long Text is written later

than the Short Text. I believe he is correct about the Short

Text as late, but that instead the Long Text's

traditionally-held dating is right, their order needing to be

reversed. Julian would surely have been too old at 85-90 for

such a drawn-out magnum opus. Similarly

with Piers Plowman drastic revision is now in order:

Jill Mann, ' The Power of the Alphabet: A Reassessment of the

Relation between the A and B Version of Piers Plowman' The

Yearbook of Langland Studies 8 (1994), 21-50, discusses A

as not the first but a later edition of Piers Plowman,

where Langland shortened and toned down his magnum opus to

comply with political changes, and yet preserve it, allowing it

continued circulation/

In 1401 the death penalty, De

Heretico Camburendo, the Burning of Heretics, had been

instituted for such teaching, and William Sawtre, Margery

Kempe's curate of St Margaret's Church, Lynn, had already been

so burned in chains at Smithfield./10

/10.

David Wilkins, Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae

(London, 1737), III.252-260: William Sawtre first on trial

before Bishop Le Despenser of Norwich in Lynn, 1 May 1399,

renouncing his errors, amongst them stating Christ in flesh and

blood was more worthy of worship than the mere wood of a cross,

25 May 1399, two years later burned, 26 February 1401, as a

relapsed heretic, Despenser bringing evidence to his London

trial. Augustus Jessop, Diocesan Histories: Norwich

(London: SPCK, 1884), pp. 137-138: 1389, Despenser only Bishop

suppressing Lollardy; 1399, opposed Henry IV, arrested,

imprisoned, 1401, reconciled./

In 1405 Archbishop Richard le

Scrope was executed at York, by order of King Henry IV,

following a scaffold sermon on the Five Wounds, it taking

three blows of the sword to kill him, which Brigittines then

took up as part of their propaganda for founding Syon

Abbey./11

/11.

Bodleian Library, Lat.lit. f.2=Arch.f.F.11, fols. 58v-60,146v;

John Rory Fletcher, Syon Abbey Notebook 3, Exeter University

Library./

In 1407-09, Chancellor Archbishop Arundel published

his Constitutions , requiring the

licensing of preachers and ownership of vernacular Bibles,

prohibiting the translating of the Bible into English and

limiting writing in the vernacular to such texts as the Creed,

the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, and standard

doctrine. In 1411 at the Carfax at Oxford, and in 1413 in

front of St Paul's, John Wyclif's books were publically

burned. In 1413 there was further alarm as the Lollard Sir

John Oldcastle escaped from the Tower and the Oldcastle Rising

was in full swing./12

/12. We

see evidence of the censorship in Nicholas Love's license from

Archbishop Arundel for his Myrrour of the Blessed Lyf of

Jesu Crist, and in Syon Abbey's Myroure of oure Lady,

the latter noting no one 'shulde haue ne drawe eny texte of

holy scryptyre in to englysshe wythout lycense of the bysshop

dyocesan ', which its writer has obtained, 'therfore I

asked & haue lysence of oure bysshop to drawe suche thinges

in to englysshe to your gostly comforte and profyt. so that

bothe oure consyence in the drawynge and youres in the hauynge.

may be the more sewre and clere ', ed. John Henry Blunt,

EETS Extra Series 19, p. 71./

Therefore, given such a context, I concur with

Nicholas Watson's observations concerning a later date for the

Short Text, and take very seriously indeed the Amherst Manuscript version's own

date of 1413, believing that it was written then, or rather

dictated to a scribe, by a most courageous Julian at 70.

For in the Short

Text Julian seems to comply with Archbishop Arundel's

1407-1409 Constitutions: revising the text; excising swathes

of scriptural material; adding and engrossing a sentence on

the Pater Noster,

the Ave and the

Creed (A109v); also adding and engrossing St Cecilia's three

neck wounds, seeming to conflate those of the Roman martyr,

who went on preaching for three days despite those mortal

wounds, with those of the English Archbishop of York Richard

le Scrope's three neck wounds at his 1405 execution, saying

she has been told of St Cecilia by 'a man of Holy Kirk

', (A97.8-9); speaking of the now-mandatory worshipping of ' Payntyngys of crucefexes', albeit with some distaste (A97.16-17), and

protesting she had never meant to teach theology (A101.4-16).

The penalty for teaching or writing theology in English from

the Bible at this date was death, either by being burned in

chains or by hanging, drawing and quartering or both, the

crime and the punishment being simultaneously heresy and

treason. Such statements would not have been made at an

earlier time, either close to 1373 or between 1388-1393, when

scriptural study was instead encouraged rather than condemned.

Moreoever the coeval Norwich Castle Manuscript complies with

writing on the Lord's Prayer, and giving Carmelite Richard

Lavenham's doctrinal Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins. It was

around 1413 that Margery Kempe

from Lynn visited Julian in her anchorhold at St Julian's and

even courageously visited Archbishop Arundel himself at

Lambeth Palace, those two talking theology in the Palace's

garden under the stars ./13

/13.

The Book of Margery Kempe, EETS 212.42-43, 36-37. She is

threatened by another woman at Lambeth with being burned at

Smithfield. For evidence of the difficulties for women studying

theology, see Ralph Hanna III, 'Some Norfolk Women and Their

Books, ca 1390-1440,' The Cultural Patronage of Medieval

Women, ed. June Hall McCosh (Athens: University of Georgia

Press, 1996), pp. 288-305, where he discusses Margery Baxter and

Avis Mone on trial, their leader William White burned, under

Bishop Alnwick of Norwich, 1428-31./

Sawtre, Margery's curate, had

been the first person executed in England during these purges.

Margery herself was often imprisoned, put on trial by bishops,

and frequently threatened with death. The words of the two

texts, Julian's Amherst Showing of Love and The Book of Margery Kempe resonate

with each other, almost as if we are listening to Julian in

stereo. Both texts speak of God in the city of our soul, the

body as its temple. Both thus argue from Paul in the Bible, at

the risk of their lives, that their women's bodies do not

exclude them from Christ's Church. Both texts quote material

concerning the Discernment of Spirits (A114v-115, M21) from Birgitta of Sweden 's

Revelationes, in its Epistola

Solitarii , written not by Birgitta of Sweden

herself, but by her editor, Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jaén,/14

/14.

Eric Colledge, 'Epistola solitarii ad reges : Alphonse of

Pecha as Organizer of Birgittine and Urbanist Propaganda', Mediaeval

Studies 18 (1975), 19-49; Arne Jönsson, Alfonso of

Jaén: His Life and Works with Critical Editions of the

'Epistola Solitarii', the 'Informaciones' and the 'Epistola

Serui Christi (Lund: Lund University Press, 1989); St

Bridget's Revelationes to the Popes: An edition of the

so-called Tractatus de summis pontificibus (Lund:

University Press, 1997); Hans Torben Gilkaer, The Political

Ideas of St Birgitta and her Spanish Confessor, Alfonso Pecha:

Liber Celestis Imperatoris ad Reges, A Mirror of Princes,

Odense University Studies of History and Social Sciences 163;

Hope Emily Allen, Book of Margery Kempe, EETS 212,

pp.lviii-lix, noting connections between Adam Easton, Alfonso of

Jaén and Margery Kempe; Rosalynn Voaden, 'The Middle English Epistola

solitarii ad reges of Alfonso of Jaén: An Edition of the

Text in British Library MS Cotton Julius F ii, Studies in St

Birgitta and the Brigittine Order, ed. James Hogg

(Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 1993),

I.142-179./

and echoed in turn in the Defensorium Sanctae

Birgittae, written by a Norwich Benedictine, one Adam

Easton.

Of interest also is that

this Amherst Manuscript, the earliest extant of Julian's Showing

of Love, survived because it was safely within the

cloisters of Brigittine Syon Abbey

and Carthusian Sheen Priory,/15

/15.

Michael G. Sargent, James Grenehalgh as Textual Critic,

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universität

Salzburg, 1984, 2 vols, gives the Amherst Manuscript's

Syon/Sheen matrix. The manuscript is not in Julian's Norwich

dialect but that of Grantham, Lincolnshire: Margaret Laing,

'Linguistic Profiles and Textual Criticism: The Translations by

Richard Misyn of Rolle's Incendium Amoris and Emendatio

Vitae ', Middle English Dialectology: Essays on Some

Principles and Problems, ed. Margaret Laing (Aberdeen:

Aberdeen Univesity Press, 1989), pp. 188-223, its first two

texts being the Lincoln Carmelite Prior Richard Misyn's

translations of Richard Rolle for the recluse Margaret

Heslyngton, 1434-1435, later than Julian's dates. The subsequent

library of texts in the Amherst, which could represent Julian's

own contemplative library, here copied for female contemplative

readership, such as the nuns at Syon, may initially have reached

Lincoln through Bishop William Alnwick's calling in of

theological texts written in English when he was Bishop of

Norwich, in compliance with Arundel's Consitutions. Bishop

Alnwick, after first placing Margery Baxter and Alis Moon on

trial for daring as women to propogate theology, 1428, was

translated to Lincoln. Furthermore Carmelite Richard Misyn went

from Lincoln to York, becoming Archbishop Richard le Scrope's

Suffragan. Present in East Anglia, York and Syon were Brigittine

monks, among them Brother Katillus Thorberni, seeking to

establish a foundation in England. The Lincolnshire Amherst

scribe is responsible for two other manuscripts, one of them,

Mechtild of Hackeborn's Book of Ghostly Grace , for

Richard and Ann of York. Mechtild's text was also present in the

Vadstena library, Sweden, in numerous copies, its earliest one

bound together, like Amherst, with Richard Rolle, Uppsala

University Library, C17, transcribed by Brother Katillus

Thorberni, who was at York, East Anglia, and Syon, 1408-1421.

This same Brother Katillus is the scribe of Uppsala University

Library, C193, which gives Cardinal Adam Easton and Hildegard of

Bingen: Monica Hedlund, 'Katillus Thorberni, A Syon Pioneer and

His Books', Birgittiana 1 (1996), 67-87./

following that, in the hands of recusant families in

England. The earlier exemplars in Norwich were destroyed,

likely either by Arundel's Constitutions for being Lollard, or

by the Reformation for being Catholic. Though Ian Doyle cannot

rule out the possibility that this section of this manuscript

was written, as it says, in 1413.

Clustered with Julian's text in the Amherst

Manuscript are others of great interest, one of them Marguerite Porete

's Mirror of Simple Souls,/16

/16.

Published as by a male Carthusian, and with the imprimatur,

in the same series of Orchard Books, as which presented Julian's

Showing in our century being then unaware that first the

text and then its authoress had been burned at the stake in 1310

in Paris: [Anonymous], The Mirror of Simple Souls, ed.

Clare Kirchberger (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1927; Revelations

of Divine Love Shewed to a Devout Ankress, by Name Julian of

Norwich, ed. Dom Roger Hudleston, O.S.B. (London: Burns,

Oates and Washbourne, 1927). Its Middle English version in the

Amherst Manuscript and in two others is accompanied by an

authorizing gloss written by one' M.N.' Paul Verdeyen, 'Le

procès d'inquisition contre Marguerite Porete et Guiard de

Cressonessart, Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique 81

(1986), 47-94./

who was condemned on the basis of XV Articles by 21

doctors of theology of the university for the writing of that

book, her Inquisitors including Victorines, Carmelites, Austin

Canons, Cistercians and Benedictines, the Franciscan Nicholas of Lyra among them.

Scholars on the Continent now claim that Marguerite Porete

's Mirror of Simple Souls, influenced by Guillaume de

Thierry's Golden Epistle and Pseudo-Dionysius'

writings, next influenced Meister Eckhart and

the Friends of God movement.

Another work called the Golden Epistle, Marguerite Porete

's Mirror of Simple Souls, Jan

van Ruusbroec 's Sparkling Stone and an extract

from Henry Suso 's Horologium

Sapientiae, in Middle English are all included with the

earliest surviving Julian's Showing text in the Amherst Manuscript.

With this hypothesis, of

a woman able to write outstanding theology at 25, in 1368, in

the Westminster Manuscript

(W); at 45-50, in 1388-1393, in the Paris Manuscript (P); and at

70, in 1413, in the Amherst

Manuscript (A), I next sought not just the evidence

within her surviving manuscripts, where I first encountered

it, but that of her own life's context. /* Fresco, Westminster Abbey, of Benedictine

monk in prayer. Westminster and Norwich were both Benedictine

houses in the Middle Ages. /

And that was when I discovered a similarly brilliant Norwich

Benedictine. Let me introduce you to a young working class

novice named now Adam Easton

, but who wrote his name as 'OESTONE' or 'Eston', perhaps from

the village six miles to the west of Norwich, or who could

have been 'OEstrewyk', 'Westwick', in Norwich's Jewry, whose inhabitants once paid

for the building of this Cathedral, who would have paced the

floors of this cathedral, and of this cloister, and read the

manuscripts in its library and written manuscripts in its

scriptorium./17

/17. De

S. Birgitta vidua, Acta

Sanctorum [ASS]

(Paris: Victor Palme, 1867), October 8, Oct IV, vol. 50, 369A,

412A, 468A, 473C; Leslie John MacFarlane, 'The Life and Writings

of Adam Easton, O.S.B.', University of London, Doctoral Thesis,

1955, 2 vols; Eric College, A Syon Centenary (Syon

Abbey, 1961), pp. 5-6; Margaret Harvey, The English in Rome, 1362-1420:

Portrait of an Expatriate Community (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 188-237. Adam Easton now

has a website: http://www.adameaston.info/

whose webmaster has also published this material as a book.

Amongst his schoolboy

manuscripts are studies of Arabic mathematics and astronomy.

One of these, now at Cambridge University Library, has his

drawings of how to measure the height of the spire of this

Cathedral and of the walls of Norwich Castle, in which these

structures are clearly recognizable,/18

___

___

/18.

Cambridge University Library Gg.VI.3, fols. 318,320, Norwich

Cathedral Priory shelfmark, X.clxx. Another Easton manuscript on

astronomy is Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 347, mentions St

Dionysius, fol. 156v./

while also giving Grosseteste's Tractate on Squaring

the Circle.

Adam Easton, together with

Thomas Brinton, was sent to study at Oxford in 1350 where he

was soon teaching the Hebrew of the Old Testament. He also

discovered during this period the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius ,

who was thought in the Greek and Latin Churches to be the

Dionysius converted by Paul on the Areopagus in Athens,

together with the woman Damaris, in Acts 17./19

/19.

Thomas Aquinas quoted Pseudo-Dionysius 1,700 times, believing

him to be the Dionysius of Acts 17.34, and therefore an

Apostolic Father; John Whiterig discusses him and Julian of

Norwich also wrote of ' Seynte dionisi of france whyche

was that tyme a paynym ' (P37-37v)./

Actually Pseudo-Dionysius is a Syrian

theologian, who lived several centuries later, and who

pretended to be the converted Athenian Dionysius. That's why

we call him 'Pseudo-Dionysius'. He wrote marvellous but flawed

theology. He invented, for instance, the most un-Christian

word and concept, 'hierarchy '. Unlike Christ's Gospels, he believed

intensely in hierarchies in the Church and among Angels. For

this reason Emperors and Kings, both East and West, sought his

collected Works and propagated them in manuscripts,

one of which Adam Easton himself owned. It's a beautiful

manuscript, in Latin and Greek, and the prayer to the Trinity as Wisdom is

illuminated with a most lovely Romanesque

in gold

leaf, lapis lazuli blueand leafy green

intertwines./20

in gold

leaf, lapis lazuli blueand leafy green

intertwines./20

/20.

Cambridge University Library Ii.III.32, fol. 108v, Norwich

Cathedral Priory shelfmark X.ccxxviii (highest surviving

manuscript number of the six barrels of books Easton willed to

his monastery). Another of Easton's manuscripts, Origen, Homelia

in Leviticum, Cambridge University Library, Ii.I.21,

Norwich Cathedral Priory shelfmark X.cxx, includes, ' Aut tibi

videtur Paulus cum ingressus est theatrum, vel cum ingressus est

Areopagum, et praedicavit Atheniensibus Christum, in sanctis

fuisse? Sed et dum perambulasset aras et idola Atheniensium ubi

invenit scriptum ''Ignoto Deo'''; Origen's texts, written

for nuns, are particularly sensitive to women in the Bible,

discussing for instance the woman touching Christ's fringed

garment. Both the Cloud Author and Julian also use that

episode. Easton makes notes in the manuscript on priesthood./

Recall that the Kings of France are buried at

the Benedictine Abbey of St Denis outside Paris, the French

believing that this St Dionysius, their patron, St Denis, had

written the theology Adam and Julian used, and even that he

was also the martyred Apostle to France, who was beheaded on

Montmartre, then picked up his head and carried it about, all

as well as having been Paul's convert in Athens! The Gothic style, and its later

ramifications, which this Cathedral and East Anglian churches

came to use, /* Walsingham's

Slipper Chapel, which survived the Reformation. I photographed

it on pilgrimage there./ and

which I showed at the lecture with a slide of Walsingham's

Slipper Chapel, but which I can illustrate here with the

cathedral itself in which this lecture was given,

_

_

Walsingham, Slipper

Chapel

Norwich Cathedral, West Nave and Window

began at the Benedictine Abbey of St Denis in

response to Pseudo-Dionysius' Neoplatonist delight in

hierarchy, mirroring it in stone tracery and glass. Similarly

the Victorine monks poured over Pseudo-Dionysius, weaving from

the text an elaborate theology, Easton himself being

thoroughly immersed in the writings of Hugh and Andrew of St

Victor on the priesthood. Abelard, alone, himself a monk of St

Denis, observed the fraudulence of all this legendary material

- for which he was not popular. The King of France's authority

and the hierarchy of the French church and state greatly

depended upon it. Interestingly, Julian does not like

hierarchies but speaks instead of our 'even-Christians'. Nor

does she appreciate the way clerks revere the ranks of angels,

and she says so in the Showing of Love (P166v), in

what is perhaps a dig at Pseudo-Dionysius,

Adam Easton and Walter Hilton

, all of whom were writing on angelic hierarchies, Julian

speaking instead of our 'oneing' as Adam, directly with God, who created us

in that image, which is his own.

Adam Easton was very happy at Oxford. Arabic

mathematics, Hebrew philology, and Greek theology suited him

fine. He was fascinated with time and eternity, with how to

measure smaller and smaller amounts of time. He was also

intrigued by time's immensity and writes out dates in arabic

numerals, including those we would expect, 1368, 1373, but

going on to not just our year 2000, but the years 40,000,

80,000, 100,000. He hated wasting time. Julian shares that

concern (P134,141v,160v). Adam Easton was as well deeply

versed in spirituality. A Benedictine student who overlapped

with Adam Easton at Oxford was John

Whiterig , who later became a Hermit on Farne Island,

writing on St Cuthbert, and in the Meditationes, on

Jesus as Mother, which Julian will quote in her Showing.

Amongst Easton's lost Dionysan/Victorine writings, perhaps

destroyed at the Reformation, are a work on the 'The

Perfection of the Spiritual Life', and translations into the

vernacular./21

/21.

'Totum vetus Testamentum ex Hebraeo vertit in Latinum', De

perfectione vite spiritualis, 'De diuersitate

translationum', 'De communicatione ydiomatum', 'De sua

calamitate', amongst numerous other titles: John Bale, Scriptorum

Illustrium Maioris Brytannie, quam nunc Angliam et Scotiam

vocant: Catalogus (Basle: Opinorum, 1557-1559); Ioannis

Pisei Angli, Relationvm Historicarvm de Rebus Anglicis

(Paris: Thierry and Cramoisy, 1619), I.548-549; Index

Britanniae Scriptorum, ed. Reginald Lane Poole and Mary

Bateson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902), pp. 4-6./

He lived an active life as teacher and diplomat but

yearned, too, like John

Whiterig , to be a solitary, a hermit, an anchorite. I

believe he was to make Julian be his contemplative surrogate

while he paced corridors of power.

However, the Bishop of Norwich wanted him back

from Oxford, along with a fellow Benedictine, ' Jo', likely the

brilliant John Stukley. In 1352, Adam wrote to the Pope

begging to be allowed to continue working towards his degree,

appealing against his Bishop./22

/22.

Joan Greatrex, Biographical Register of the Priories of the

Province of Canterbury circa 1066-1540 (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1997), pp. 502-503; John Lydford's Book, ed.

Dorothy M. Owen, Historical Manuscripts Commission, Devon

and Cornwall Record Society 19 (1974), 201, p. 106; 202,

p. 107; ' A de E, monk of Norwich appeals again to Holy

See to remain at Oxford until 12 June 1352', 20

(1974), 202. For a sense of the intellectual milieu of medieval

Norwich Cathedral Priory, see William Courteney, Schools and

Scholars in Fourteenth-Century England (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1987), p. 275: ' Stuckely

discussed the infinite capacity of the soul for beatitude, the

latitude of forms, finite and infinite intensities, the

augmentation and diminution of grace, maxima and minima,

modal and tensed propositions, qualitatitive and quantitative

infinites, the relation of grace and free will, predestination,

divine responsibility for sin, and the possibility of the

meritorious hatred of God' ./

The Prior of this Cathedral next demanded he and

Thomas Brinton return and that they bring back with them all

their books and plate. Benedictines must obey their Abbot or

Prior as if he were Christ. So Adam and Thomas now dutifully

came back to Norwich and were here from 1356 to 1363./23

/23.

Joan Greatrex notes Easton preached in Norwich, Feast of

Assumption, 14 August 1356, Norwich Record Office [NRO], DCN

1/12/29. Brinton's sermons survive, but not Easton's, The

Sermons of Thomas Brinton, Bishop of Rochester (1373-1389),

ed. Sister Mary Aquinas Devlin, O.P., Camden Third Series 85

(London: Royal Historical Society, 1954); Langland, Piers

Plowman, ed. Walter W. Skeat, I.14-18, B. Prologue

139-215, based on Brinton's Sermon 69, II.317, allegory of

Parliament and John of Gaunt, where rats and mice debate belling

the cat; motif on Malvern Priory misericordia. Norman Tanner

says Benedictines' sermons to the laity were lively, learned and

appreciated, The Church in Late Medieval Norwich 1370-1532

(Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1984), p.

11; William Courtenay notes commitment to Biblical study,

encouraged by the Papacy and the laity, including translation

into the vernacular, excellent preaching, production of

devotional treatises and participation in the controversy raging

about Wyclif, characterized this period, 'The 'Sentences' -

Commentary of Stukle: A New Source for Oxford Theology in the

Fourteenth Century', Traditio 34 (1978), 435-438; Schools

and Scholars, pp. 275, 373; Grace Jantzen, Julian of

Norwich (London: SPCK, 1987), p. 22./

The Prior needed Adam Easton and Thomas Brinton to

preach to the Norwich laity to woo them back from the

Franciscans and the Dominicans, from the Carmelites and the

Augustinians, who were becoming far too powerful and casting

this vast Benedictine Cathedral into the shadows./24

/24.

Prior of Norwich explains to Prior of Students at Oxford that he

cannot yet send Adam Easton back to incept at Oxford, as he is

needed at Norwich to help with the preaching and in silencing

the Mendicants, promises to restore him to the bosom of the

university in a year: Documents Illustrating the Activities

of the General and Provincial Chapters of the English Black

Monks 1215-1540, ed. William Pantin, Camden Third Series

45, 47, 54 (London: Royal Historical Society, 1931-1933, 1937),

3.28-29, from Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 682, fol. 116./

We learn that the sermons of the two young men were

lively and well-attended by the laity. Adam's sermons could

have included such material as Pseudo-Dionysius on God in a point , on God as

'I am' (Julian's 'I it am

'), on God as Mother ,

on the Bible text translated directly from Hebrew into Middle English, and on

the Trinity as Might,

Wisdom and Love. All of this material is in Julian's '1368' Westminster Manuscript . During

this period Easton copied out polemical works against the

Franciscans, even illuminating in one of them grey-clad

Franciscans, black-and-white clad Dominicans, white-clad

Carmelites and grey-clad Augustinians, with devils at their

throats./25

/25.

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 180, Richard FitzRalph, Bishop

of Armagh, writing against the Friars, Norwich Cathedral Priory

shelfmark, X.xlvi, LIBER:DNI/DE:OESTONE:/MONACHI:

NOR/WICENSIS' at fol. 88. The illumination of the opening

folio recalls Julian's account of the devil at her throat

(P142v, A111v), while a similar 1350 Norwich episode is given in

Lambeth MS 432, fol. 87-87v. A companion manuscript is William

St. Amour, Bodleian Library, Bodly 151, 'Liber

ecclesie Norwycensis per magistrum Adam de Estone monachum dicte

loci ', Norwich Cathedral Priory shelf mark X.xlvi./

Finally he was able to return to Oxford being Prior

of Students there, 20 September 1366./26

/26.

Greatrex, citing Pantin, Black Monks , 3.60./

We have a huge bill paid for the shipping by wagon

of the manuscripts, 113 shillings and threpence./27

/27.'In expensis

Ade de Easton versus Oxoniem et circa cariacionem librorum

eiusdem, cxiijs iiid '. Greatrex notes total cost, 154s. 8d,

NRO DCN 1/12/30, Sacrist contributes to his inception, NRO DCN

1/4/35, Refectorer, NRO DCN 1/8/42, Master of Cellar, 30s, to

'master of divinity', NRO DCN 1/1/49./

Julian's largest legacy, from Isabelle, Countess of

Suffolk, was a mere 20 shillings. Among those manuscripts

would have been Pseudo-Dionysius' Works, Origen on

Leviticus, perhaps one by Rabbi

David Kimhi on Hebrew philology, in Hebrew,/28

/28.

David Kimhi, Sepher Ha-Miklol (Book of Perfection) Sepher

Ha-Shorashim (Book of Roots), Cambridge, St John's College

218 (I.10); The Longer Commentaries of R. David Kimhi on the

First Book of the Psalms, trans. R.G. Finch, intro. G.H.

Box (London: SPCK, 1919), p. 16, noting of Deuteronomy 32.18, ' He is to

you as a father, and the one that gave thee birth - that is the

mother'. Easton's schoolboy manuscripts, now in

Cambridge University, are on time, originally written here. He

came back again to Norwich, in 1367-1368, and at the same time

that Julian may have been writing the Westminster

Cathedral Manuscript (W)'s original version at 25.

Next, and now addressed as 'Master', Adam Easton

left Norwich to work for Cardinal Langham at Avignon where the

Pope was then residing. It was at Avignon that Master Adam

Easton came to own John of Salisbury's Policraticus,

now at Balliol, by writing it out himself./29

/29.

Oxford, Balliol 300b, Norwich Cathedral Priory shelfmark

X.clxxxxiii, with Easton's marginalia to passages used in Defensorium

Ecclesiastice Potestatis, such as, 'Respublica

beata est quando per sapientiam gubernatur ', fol.

63./

Julian will use its political language again and

again in her 1388-1393 Long Text. Adam Easton was

professionally jealous of his Oxford colleague, John Wyclif,

and wrote to the Benedictines at Westminster Abbey asking that

they send him reports on Wyclif's Oxford lectures against the

Benedictines./30

/30.

Westminster Abbey Muniment 9229*. Its scribe is the second, and

un-English, hand in Easton's John of Salisbury's Policraticus

, Balliol 300b, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol

College, Oxford , ed. R.B. Mynors (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1963), p. 320./

Wyclif and Julian were for Gospel equality, Easton

for Dionysian hierarchy. While at the Papal Curia in Avignon

and later in Rome, when the learned and ambitious Adam Easton

himself became Cardinal, he came to know Birgitta of Sweden

and Catherine of Siena

, and learned to admire them for their visionary writings.

Perhaps because he already knew of a Norwich lass, writing a

similar book. And perhaps because he already knew of Birgitta's Revelationes .

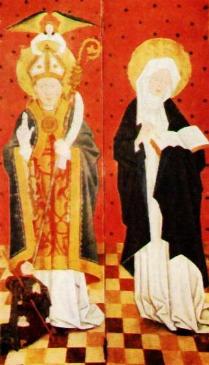

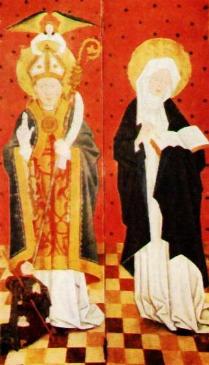

Diptych of Bishop Hemming of Turku, Birgitta of

Sweden, Urdiala, Finland

At this point we need to voyage across the

Northern Sea to Scandinavia, to Finland and Sweden. /* Urdiala, Finland, Diptych of Bishop Hemming

of Åbo, Finland, being mitred by an angel, and Birgitta of

Sweden, in the act of writing the Revelationes . For a

study of Birgitta in art, especially as writing her Revelationes

, see Mereth Lindgren, Bilden av Birgitta (Hoganas:

Wiken, 1991)./ This diptych shows

Bishop Hemming of Abo, Finland, and

Birgitta of Sweden , whom he

encouraged to write her Revelationes, her visions.

Birgitta was a Swedish noblewoman, mother of eight children,

widowed young, who had had an important vision in Arras in

France when returning from pilgrimage to Compostela in 1342,

the year Julian was born, and in which St Dionysius had

spoken to Birgitta of the need for peace between the Kings

Philip VI of France and Edward III of England./31

/ 31. Revelationes

IV.104-5 ; Bodleian, Ashmole Rolle 26 (olim 27), verso,

gives letter/vision for Edward III, Philip IV, 'Orante xi

sponsa Beata Birgitta vidit in visione qualiter beatus Dionisius

orabat pro Regno francie ad virginem mariam Libris Xo Celestium

Revelacionem '; Colledge, 'Epistola', cites similar

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 404, fol. 102v./

Birgitta even sent envoys from Sweden to the Kings

of England and of France and to the Pope, in 1347-1348,

pleading for peace in Europe and the end to the Hundred Years'

War, those envoys including Prior Petrus and this Bishop Hemming , who conveyed the

text of her visions, the Revelationes, or Showings,

introduced by Magister Mathias , a Swedish

scholar who had studied Hebrew in Paris./32

/32. Revelationes

I.3.8-9: ' Iste fuit quidam sanctus vir, magister in

theologia, quo vocabatur magister Mathias de Suecia, canonicus

Lincopensis. Qui glosauit totam Bibliam excellenter. Et iste

fuit temptatus a diabolo subtilissime de multis heresibus contra

fidem catholicam, quas omnes deuicit cum Christi adiutorio, nec

a demone potuit superari, ut in legenda vita domina Birgitte hoc

clarius continetur. Et iste magister Mathias composuit prologum

istorum librorum, qui incipit 'Stupor et mirabilia' etcetera.

Fuit vir sanctus et potents spiritualiter opere et sermone'

Magister

Mathias ' commentary on

Apocalypse, based in part on that of Nicholas of Lyra under whom he

studied, influenced St Bernardino of Siena, Colledge, '

Epistola', p. 22, likely reaching Siena by way of Alfonso of Jaén who had Sienese

ancestry and who returned there in connection with Catherine

of Siena. Magister Mathias refers to Cardinal Jacques de

Vitry's support of the beguine Marie

d'Oignies , a model Margery Kempe's scribe also used./

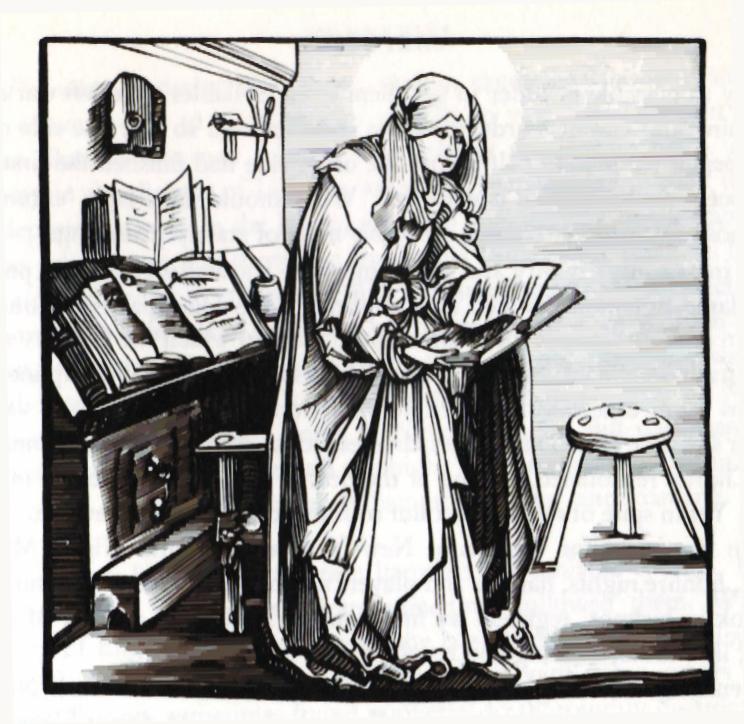

/* Manuscript illumination, Birgitta of

Sweden's Revelationes, Book V./ Magister Mathias was brilliant, filled with

doubts, and Birgitta proceeded to teach him his theology,

writing this out in her vision of the ladder in Book V, the 'Book of Questions ', of the Revelationes,

which came to her while journeying to the King's Palace at

Vadstena, to be given to her for her convent. Julian, and her

editor, will quote this text in her Long Text and Short Text Showing

of Love (P59,93,153-155v, A107).

St Birgitta, Revelationes V, Book of the

Questions, Doubting Monk (Magister Mathias) on Ladder,

Nurenberg: Anton Koberger, 1500.

Thus England had already known of a woman's

text called the Revelationes, the Showings, twenty

years before Julian's hypothetical writing of the initial

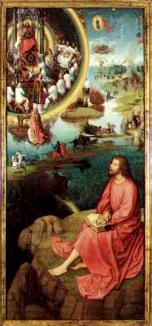

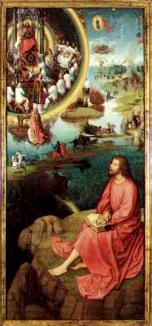

version of her Revelations or Showings./* Hans Memling, 'John Writing Revelation on

the Island of Patmos', St John's Hospital, Bruges./

Hans Memling, St John Writing Revelation, St John's

Hospital, Bruges

Birgitta's Revelationes are modeled upon

John's Revelation, the Book of the Apocalypse, but written by

a woman instead of a man. including the theme of theological

doubting by men, countered by women's faith. It is also likely

that those Baltic envoys disembarked at one of the Norfolk

ports like Lynn. (In 1415 the Swedish Brothers and Sisters

from Vadstena's Abbey so came to help Henry IV/Henry V found

the English Brigittine Syon Abbey

where Julian's manuscripts were to be so carefully preserved,

Katillus Thorberni, coming from Vadstena on preparatory

mission in England, 1408.) Perhaps the embassy visited

Norwich, then the second largest city in England, on their way

to King Edward III. The young Benedictine, Adam Easton, had

not at that date left Norwich Cathedral Priory for Oxford

University. Prior Petrus and Bishop Hemming could have been

here, within these very cathedral walls, with that early

version of Birgitta's Revelationes or Showings in

their hands .

Spanish Chapel, Santa Maria

Novella,

Florence X See

detail below

/** 'Via Veritatis' fresco, Spanish Chapel,

Santa Maria Novella, Florence, of Birgitta's prophecy of Pope

and Emperor meeting, as they did in 1368, with Birgitta as

black and white clad widow, her beautiful, simply-clad,

daughter, Catherine of Sweden, beside the crowned Queen Joanna

of Naples and behind Lapa Acciaiuoli, extreme right./ During the Black Death Birgitta herself left

Sweden herself and came to Italy in 1350. In this political

allegory painted on the walls of the Spanish Chapel in Santa

Maria Novella, in Florence, we can see to the extreme right Catherine of Siena ,

Birgitta of Sweden , her daughter

Catherine of Sweden, Queen Joanna of Naples and Lapa

Acciaiuoli, sister of Nicolo Acciaiuoli, who out of his guilt

for his sins, had built the vast monastery of Certosa outside

of Florence and who had died in Birgitta's presence, 8

November 1366./33

Queen Joan of Naples, Catherine

of Sweden, Birgitta of Sweden, Lapa Acciauoli

/33.

Millard Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the

Black Death: The Arts, Religion and Society in the

Mid-Fourteenth Century (New York: Harper and Row, 1973),

pp. 86, 88, 91, 125; Anthony Luttrell, 'A Hospitaller in a

Florentine Fresco: 1366/8', Burlington Magazine 114

(1972), 362-66; Julia Bolton Holloway, 'Saint Birgitta of

Sweden, Saint Catherine of Siena: Saints, Secretaries, Scribes,

Supporters', Birgittiana 1 (1996), 29-45./

Birgitta continued writing her

Revelationes, her Showings, throughout her whole long

life, now with the assistance and oversight of a Spanish

Bishop become Hermit, Alfonso of Jaén, who first was drawn

into her circle in 1368, the year that Birgitta of Sweden

succeeded in bringing both Pope Urban V from Avignon and the

Emperor Charles from Prague, to Rome.

St Birgitta, Revelationes,

Nurenberg: Anton Koberger, 1500.

Birgitta of Sweden gives her completed Revelationes

to her editor, Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jaen, the friend and

associate of Cardinal Adam Easton, Benedictine of Norwich,

from Lubeck: Ghotan, 1492 editio princeps.

/** Illuminated manuscript page in Siena,

showing Birgitta in the act of writing the Revelationes,

within the Revelationes./

Another illustration of Birgitta in the act of writing comes

from a manuscript written for Cristofano Di Gano, one of St Catherine of Siena 's

disciples and scribes, giving the entire Revelationes

of St Birgitta, translated into Sienese Italian and today

still in Siena;/34

/34.

Siena, Biblioteca Communale degli Intronati, I.V.25/26,

Colophon: 'Compagnia de la vergina maria di siena, posta

nell ospedale di sancta maria della scala. E fecelo faro Ser

xpofano di gano da siena. Frate notaio del detto spedale.

Pregate dio per lui'. This is Catherine's cenacolo, which

had accompanied her to Avignon in 1376, and which is still

active eighteen years after her death, this manuscript being

written out in 1399 and still in Siena./

while Christopher Di Gano's translation into Latin

of Catherine's Dialogo in Sienese Italian will come to

England and eventually be printed as The Orcherd of Syon./35

/35. The

Orcherd of Syon ed. Phyllis Hodgson and Gabriel M. Liegey,

EETS 258; Phyllis Hodgson, 'The Orcherd of Syon and the

English Mystical Tradition', Proceedings of the British

Academy 50 (1964), discussing its likeness to Julian's Showing.

A similar cross-fertilizing occurs between Sweden and England,

as between England and Italy, with Vadstena treasuring the

writings of English mystics Richard Rolle and Walter Hilton

amongst their manuscripts./

Another disciple to Catherine of Siena ,

and indeed her executor, was the Englishman, William Flete , who became an

Augustinian Hermit at Lecceto, outside Siena, who had, like Walter Hilton , been educated

at Cambridge,/36

/36.

Catherine of Siena's Letters 64, 66, 227, 326, etc., are to

William Flete. He wrote Remedies Against Temptations

before leaving England, he sent 'Three Letters to the Austin

Friars in England' from his hermitage in Italy: Aubrey Gwynn, The

English Austin Friars in the Time of Wyclif, pp. 96-210,

esp. 193-210/ and whose text, Remedies Against Temptations/37.

'Remedies Against Temptations : The Third English Version

of William Flete', Archivio Italiano per la Storia della

Pieta 5 (Rome, 1968), p. 223./

Julian quotes from Flete again and again in the

W,P,A Showing of Love.

Master Adam Easton returned again to England and

Norwich that same year, with a letter from Pope Urban V to

Edward III, dated 3 May, 1368. He was back in Avignon in 1369.

Julian's Westminster Cathedral

Showing version of her text was perhaps written in 1368.

I have told of its lovely opening invoking ' {O Ure gracious and

good lord ', and its vision of the Virgin at the

Nativity and the Annunciation, spoken of in the Long Text as

the First Showing (P128v).

Then we move into her most moving vision. /* Michelangelo's David's hand, which is his

own./

Hebrew has the letter that begins God's name, and

Jerusalem's and Judea's and Joshua's and Jesus's and Julian's

be the smallest letter of all yod, - and be the letter

that means ' hand '.

/* God holding Cosmos He has created, as a fragile

glass orb./

__

__

We have in medieval iconography the image of

God holding in his hand all that is, the entire universe of

which he is king, the whole cosmos as a ball, even as a

fragile glass ball, surmounted by a cross. /* Richard II, Coronation Portrait,

Westminster Abbey./

Similarly Richard II and Elizabeth II and countless

other kings and queens have held orbs,

the globe with the cross of Jerusalem at its top, in their

imaging of God at their Coronation. But here it is not God or

Edward III who holds all this fragile globe, this blue marble

astronauts see from space.

It is Julian the Anchoress, and she holds in her

hand a small thing, the quantity

of an hazelnut , and she is told generally in her

understanding - by God - that it is all that is made.

Julian, like Wisdom in Proverbs 8, like Gregory on Benedict , is

playing with God marvellous sacred cosmic games of proportion.

And she and God invite us to join in. Easton wrote that Adam

was the first High Priest. We are the Royal Priesthood,

priests and kings, each of us, being descended from Adam, in

Julian's thought.

In the following year 1370 Birgitta

of Sweden presented Pope Urban V and Cardinal Beaufort,

who was to become the next Pope, Gregory XI, another edition

of her massive book, the Revelationes , or Showings,

and in that year the Dominican Thomas Stubbes and the

Carmelite Richard Lavenham were lecturing on Birgitta's Revelationes

or Showings at Oxford./37

/37. ASS

October 4:409A: ' revelationes in scholis Oxoniensibus et

in cathedris publicis magistralibus exposuerunt magni sua aetate

doctores Thomas Stubbes, Dominicanus, Ricardus Lavynham,

Carmelita, et adhunc alii ejus generis multi circa annum domino

MCCCLXX'. /

In that year, too, the Pope appointed Henry le

Despenser Bishop of Norwich who had fought beside Sir John

Hawkwood in Italy. /* Fresco by

Paolo Ucello in Duomo, Florence, of Sir John Hawkwood.

Florence had agreed to pay Sir John Hawkwood in part with a

marble equestrian statue in his honour. They only

half-honoured that debt with a seeming marble statue./

So we now begin to see that Julian's homely

Norwich is really pan-European, with important links to

Scandinavia and to Italy. The Italians call Sir John Hawkwood,

'Gianni Acuto', whom we see here in the fresco by Paolo Ucello

in Florence's Cathedral, the Duomo. /** Ambrogio Lorenzetti's frescoes of Siena

at Peace and War, in the second where condottieri, hired

mercenary soldiers, are about to commit rape./ In Siena's Sala della Pace we can see

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's depiction of Siena at Peace, and of

Siena at War, during warfare waged by these English

condottieri. Terry Jones in Chaucer's Knight describes

them well. St Catherine of Siena was so appalled at their

brutality that she wrote to Sir John Hawkwood begging that he

take such soldiers as Henry le Despenser away from Christian

Tuscany and have them wage a Crusade instead against the

Saracen. This enthronement as bishop of a condottiere came

about because the Pope received word of the previous Bishop of

Norwich's death while Henry le Despenser was standing before

him and whom he had to pay. He did so with the Bishopric, and

constantly called upon Bishop le Despenser to wage Crusades

against fellow Christians who had elected an opposing Pope to

himself. It is not likely that Bishop le Despenser, who was

unlettered and martial, would have initially allowed Julian to

become an Anchoress in the Anchorhold at St Julian's Church in

Norwich. St Julian's Anchorhold and Church were under the

patronage of the Benedictine nuns of Carrow Priory which in

turn was under the patronage of the Benedictine monks of

Norwich Cathedral Priory./38

/38.

David Knowles, The Religious Houses of Medieval England

(London: Sheed and Ward, 1940), p. 65; Roberta Gilchrist and

Marilyn Oliva, Religious Women in Medieval East Anglia

(Norwich: University of East Anglia, 1993)./

The Benedictines of Norwich Cathedral Priory and

Bishop le Despenser thoroughly hated each other and were only

reconciled years later. It is at this point we find the first

references to Julian as being left money in wills to carry out

her work of prayer at St Julian's. She may have earned her

keep earlier, as had been typical for anchoresses, in teaching

children their ABC and their

Catechism. Under Archbishop Chancellor Arundel's Constitution

such teaching came to be forbidden by the laity.

In 1371-1373 Cardinal Simon Langham and Master Adam

Easton were asked by Pope Gregory XI to work on peace between

England and France, /39

/39.

Devlin, Sermons of Thomas Brinton, p. xiv/

in accordance with Birgitta of Sweden 's

1342 Revelation, which is copied out in English manuscripts,

giving St Dionysius

speaking to Birgitta in Arras of the need for peace between

the Kings of France and England. We have further evidence of

Easton's presence in England at this time./40

/40.

Greatrex, noting Thomas Pykis, precentor of Ely, paying 40s to

Easton's clerk, 1371-2, Cambridge University Library Add. 2957,

fol. 45./

Easton would again have returned to his mother

house, Norwich Cathedral Priory, around 1371-1373. He could

even have been the 'religious person' at Julian's supposed

deathbed, in May of 1373, for that is the term typically used

of a Benedictine monk living under vows of religion. Julian

tells us that when she told this person of her vision, of the

Crucifix 'bleeding fast', he suddenly stopped laughing and

took her very seriously indeed, of which she was greatly

ashamed (P141v, A111v). Adam Easton at this time would have

taken very seriously indeed a woman's vision, especially of

the Crucifix, /* St Birgitta's

Vision of the Crucifix Which Spoke to Her. Its iconography

collapses the 'Crucifix in San Damiano Speaking to St

Francis', with 'St Francis Receiving the Stigmata at

L'Averna'./ for that was a most

famous and recent vision his friend Birgitta of Sweden had

had, of the Crucifix which spoke to her at St Paul's Outside

the Walls at Rome, in 1368. But he would not have been the

appropriate person to whom she could then make her confession

concerning the Discernment of Spirits

, and she is greatly troubled about making that confession.

Yet Julian's vision in Norwich

is quite different from that of Birgitta's 1368 vision in

Rome. As she gazed upon the Crucifix

Julian began to see the blood flow from the garland of

thorns about Christ's head. She describes it as like the

rain upon thatched eaves - and we know that St Julian's

Church roof was thatched at this time - /41

/41.

Francis Blomefield, An Essay Towards a Topographical History

of the County of Norfolk (London: William Miller,

1805-10), IV.79; British Library, MSS Add. 23,013-65, give these

volumes with further annotations, sketches in colour, of which

the relevant materials for Julian are in Add. 23,016./

_

_

/** Medieval Norwich's riverfront Dragon

warehouse./ and she describes it

also as like the scales of herring that would have been

brought up the river so near to her church and along whose

shores merchants built vast storage barns. Along that street

also parchment was made for use by monks and friars and such

like who would have been literate in Julian's day in Norwich.

The parchment for Julian's own book, her Showing,

would have been bought by her maid in that street. For

Julian's maids Sara and Alice are named in wills made in her

favour. She herself was enclosed and could do no shopping. One

of the maids in turn perhaps became an anchoress, Alice

Hermit, leaving a silver chalice to a Norwich church in her

will. Julian simply refuses to make her crucifix vision

political in the way that Birgitta of Sweden does. Instead she

has it be homely and familiar, likening it to rain and

herring. And she also evades it, distancing herself from it,

speaking in the Amherst

Manuscript even, like a Lollard, like the executed

William Sawtre, Margery Kempe's St Margaret's chaplain, with

distaste of the now legally mandated prayers to 'paintings of

crucifixes'/42

/42.

David Aers and Lynn Staley, The Powers of the Holy:

Religion, Politics, and Gender in Late Medieval English

Culture (University Park: The Pennsylvania State

University Press, 1996), pp. 77-178./

Julian also describes what she saw in relation to

the Veronica Veil shown to pilgrims in Rome's Vatican Basilica

on Good Friday. Sister Ritamary Bradley suggests from her

words that Julian had actually travelled to Rome and seen this

precious relic. If she had so travelled to Rome she would have

likely stayed under the aegis of Cardinal Adam Easton and his

household, composed of many people from Norwich, as we see

from his Roman will, and which was headquartered at his

titular church of St Cecilia in Trastevere. Much of that

church has been altered. But to this day one can see in its

crypt the ruins of a Roman house and bath with hot springs,

the Sudatorium which features in the legend of

Cecilia's martyrdom, the fine

Byzantine apse showing the togaed Christ with scroll, Christ

as Teacher, flanked by Paul and Peter, by Cecilia and

Valerian, and by Pope Pascal I (816-821) carrying the model of

this church, and St Agatha, whom Pascal made co-patroness of

this church, as well as medieval buildings more in English,

than in Italian, style, clustering about the now Baroqued

Basilica.

In Julian's day an entire series of frescoes existed

giving the life and miracles of St

Cecilia , the marriage feast of Valerian and Cecilia,

Cecilia having Valerian seek Pope Urban I, Valerian riding to

Urban, Valerian's baptism, the angel crowning Valerian and

Cecilia, Cecilia converting her executioner, Cecilia in the

bath, the execution of Cecilia, her burial, then Pascal's

dream, of which only the last fresco survives, copies of those

which were destroyed being kept in the Barberini Library. Pope

Pascal I described how he had a vision in St Peter's of St

Cecilia where she appeared to him in golden robes telling him

of her burial place, beside her husband and brother-in-law, in

St Callixtus' Catacombs. He found them and brought them to her

church the following day, reburying her there as she was. A

sixteenth-century Cardinal then exhumed her, finding her

incorrupt lying on her side robed in gold tissue, and

commissioned Maderno, likewise an eyewitness, to sculpt her

so. The mosaic similarly garbed Christ, Cecilia, Pascal and

Agatha in cloth-of-gold./43

/43.

Augustus J.C. Hare, Walks in Rome (New York: Routledge,

n.d.), pp. 677-682, who notes English Chaucer's contemporary use

of St Cecilia, and that Cecilia is one of the few saints

commemorated daily in the Canon of the Mass, the other women

commemorated so being Felicita, Perpetua, Agatha, Lucia, Agnes,

and Anastasia./ .

St Cecilia, mosaic at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere,

Rome, commissioned by Pope Pascal I, on finding her incorrupt

body at St Callixtus

In the Renaissance that body was again found to be

incorrupt and Stephano Maderna sculpted it so, the head turned

in shame, the sword wounds upon its neck:

If Julian had been a pilgrim guest at Santa Cecilia

in Trastevere, walking beside the Tiber to Vatican St Peter's

one Good Friday, these Roman memories would have heightened

her use of the Veronica Veil, St Cecilia's martyrdom of three

neck wounds and her three days' preaching,

By Permission of the British Library, Amherst

Manuscript, Additional 37,790

and Julian's own ever-present theme of Christ as

Teacher,/44

/44. Ritamary

Bradley, 'Christ the Teacher in Julian's Showings: The

Biblical and Patristic Traditions', The Medieval Mystical

Tradition in England: Papers Read at Dartington Hall, July,

1982. Ed. Marion Glasscoe (Exeter: University of Exeter,

1982), pp. 127-142. Sister Ritamary Bradley communicated to me

that she believed Julian visited Rome, seeing the Veronica Veil

there.

Another

Roman relic Julian compellingly palimpsests upon her vision of

the Crucified Christ is that of a tawny board. 'Adam' in

Hebrew means 'tawny'. Birgitta's board of walnut upon which

she ate, wrote, and it is even said was laid at her death, is

still kept as a relic in the room become a chapel where

Birgitta lived and wrote and died, and which Margery Kempe

memorably visited, perhaps on Julian's recommendation, Santa

Brigida, Piazza Farnese, Rome, Book, EETS 212, ed.

Allen, p. 95.. See Andersson and Franzen, Birgittareliker,

pp. 33-44, 58-59./

of Christ as Master, the Galilean/Palestinian

'Master Jesus', shadowed by that of her Norwich/ Oxford

/Avignon/Rome Master Adam, become Cardinal of Santa Cecilia in

Trastevere and supporter of Birgitta of Sweden.

Birgitta

of Sweden died the same year and in the month following

Julian's illness, 23 June 1373, the vigil of Mary Magdalen,

following her return from Jerusalem in Rome, /* St Birgitta's board for writing and eating,

sleeping and dying, today still preserved in the room in which

she lived and died in Rome./

her body first being laid upon this board upon

which she customarily ate and wrote the Revelationes, /* Birgitta's Shrine in the Blue Church at

Vadstena, Sweden./

then brought home to Sweden and laid to rest in this

sumptuous shrine at Vadstena where her monastery was founded.

Catherine of Siena

was examined by the Dominicans in that year in the Spanish

Chapel, Santa Maria Novella, Florence, amidst its frescoes of

herself, her friend Catherine of Sweden and of Birgitta of

Sweden. Birgitta's director and her appointed executor, the

Hermit Bishop Alfonso of Jaén, gave Birgitta's Revelationes

to Pope Gregory XI and was next appointed by the Pope to serve

as Catherine of Siena's director./45

/45.

Alfonso of Jaén served as spiritual director to Birgitta of

Sweden, her daughter, Catherine of Sweden, also to her friend,

Catherine of Siena, and to Chiara

Gambacorta of Pisa: Ann M. Roberts, 'Chiara Gambacorta of

Pisa as Patroness of the Arts', Creative Women in Medieval

and Early Modern Italy: A Religious and Artistic Renaissance,

ed. E. Ann Matter and John Coakley (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1994), pp. 120-154./

At which point the illiterate Catherine miraculously

began writing, or rather dictating, sometimes to three

secretaries at once, letters to Popes and Emperors and even to

our King Richard II and to the Englishman Sir John Hawkwood,

the martial Bishop of Norwich's former companion as

condottiere in Italy. Catherine of Siena, like Birgitta, next

composed a theological visionary work, the Dialogo,/46

/46.

Suzanne Noffke, O.P., The Texts and Concordances of The

Works of Caterina da Siena: Il Dialogo, Le Orazioni,

L'Epistolaria ; Letters 133, 138, 143, 312, 317, 348, 362,

are written to Queen Joanna of Naples./

a copy of which which was brought here to

England, likely by Adam Easton who knew her, and translated

into Middle English, perhaps by Easton himself who is

noted to have made such translations: 'De communicatione

ydiomatum', 'De diversitate translationum', 'De perfectione

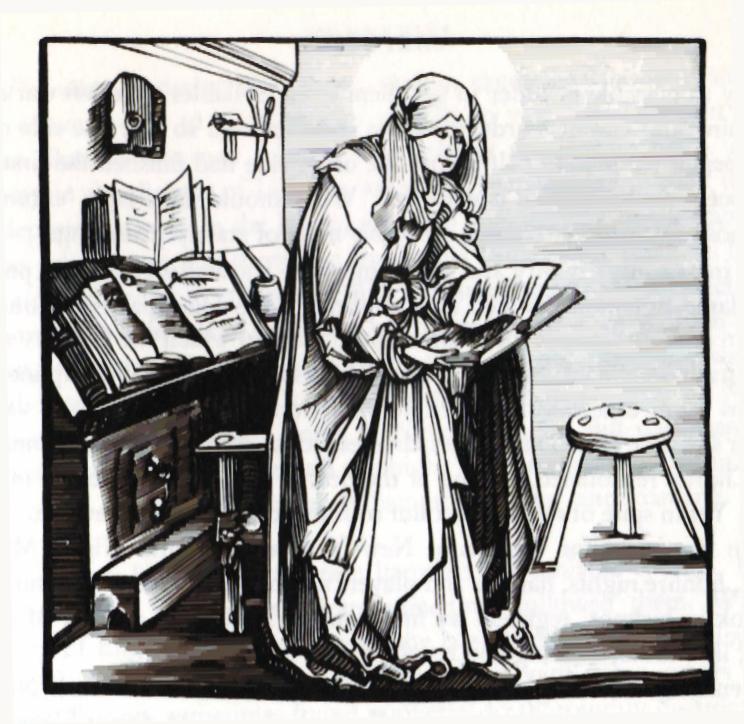

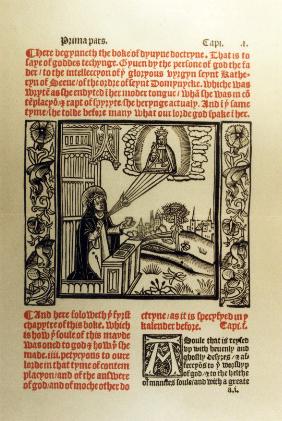

vite spiritualis'. /* Engraving

in printed Orcherd of Syon of St Catherine of Siena

receiving divine doctrine, reflecting her receiving the

Stigmata, Santa Cristina, Pisa, 1375./ , later to be printed as The Orcherd of

Syon by Wynken de Worde for Syon Abbey./47

/47. The

Cell of Self-Knowledge: Seven Early English Mystical Writers

Printed by Henry Pepwell MCXXI, ed. Edmund G. Gardner

(London: Chatto and Windus, 1910), p. xviii, notes Catherine of

Siena's connections with England though her Cambridge

University/Augustinian Hermit disciples, William Flete and

Giovanni Tantucci, and her Letter 14 to Sir John Hawkwood, and

to Richard II, the latter not surviving; David Wallace, 'Mystics

and Followers in Siena and East Anglia: A Study in Taxonomy,

Class and Cultural Mediation', The Medieval Mystical

Tradition in English: Papers Read at Dartington Hall, July

1984, ed. Marion Glasscoe (Exeter: University of Exeter

Press, 1984), pp. 169-191; Jane Chance, 'St Catherine of Siena

in Late Medieval Britain: Feminizing Literary Reception through

Gender and Class', Annali d'Italianistica 13 (1995),

163-203; Phyllis Hodgson, ' The Orcherd of Syon and the

English Mystical Tradition,' Proceedings of the British

Academy 50 (1964), 229-249. Both Vadstena and Syon had

cloistered orchards, pleasure gardens ('örtagärd',

'viridiarium'), in which the nuns could walk and talk. Alfonso

had written the Viridiarium compiled from Birgitta's Revelationes

of visions concerning Christ and Mary especially for the nuns of

Vadstena: Colledge, 'Epistola', p. 34. The connections,

as with The Orcherd of Syon , are far closer than

commonly realized between Birgitta and Catherine, Alfonso and

Adam. Vadstena in 1391 and Syon in 1415 were granted pardons,

indulgences, equivalent to St Francis' Portiuncula, Margery

Kempe mentioning this Pardon of Syon./

Transcription: ¶Here begynneth the boke of dyuyne doctryne. That

is to/ saye of goddes techyng. Gyuen by the person of god

the fa/der to the intelleccyoun of the gloryous

vyrgyne seynt Kathe-/ryn of Seene/ of the ordre of seynt

Domynycke. Which was/ wryte n as she endyted in

her moder tongue. Wha n she was in con/templacyon

& rapt of spyryte she herynge actualy. And inthe

same/ tyme she tolde before many what our lorde god spake in

her.

And here foloweth the fyrst/ chapytre of

this boke. Which/ is how the soule of this mayde/ was

oned to god & how then she/ made .iiii. petycyons

to oure/ lorde in that tyme of contem/placyon and of the

answere/ of god and of moche other do/ctryne: as it is

specyfyed in the/ kalender before. Capt.1.

A soule that is reysed

up/ with heuenly and/ ghostly desyers & af-/feccyo n

s to the worshyp/ of god 000& to the helthe/ of mannes soules with a

greate . . .

________

The Orcherd of Syon (Westminster:

Wynken de Worde, 1519), Catherine of Siena's Dialogo

in Middle English, its colophon: 'a

ryghte worshypfull and deuoute gentylman mayster Rycharde

Sutton esquyer stewarde of the holy monastery of Syon fyndynge

this ghostely tresure these dyologes and reuelacions . . . of

seynt Katheryne of Sene in a corner by itselfe wyllynge of his

greate charyte it sholde come to lyghte that many relygyous

and deuoute soules myght be releued and haue comforte therby

he hathe caused at his greate coste this booke to be prynted'.

In 1379 Alfonso of Jaén, 3

March, Adam Easton, 9 March, and Catherine of Sweden,

Birgitta's daughter,10 March, all testified on behalf of the

validity of Pope Urban VI's election./48

/48. Vatican Secret Archives, Armarium

LIV.17, fols. 46-7, 'Venerabilis et reverendus pater et

religiosus honestus magister Adam de Eston, magister magnus et

profundus in sacra pagina, monachus Norwicensis, ordinis Sancti

Benedicti, etatis XL et ultra, nacione Anglicus ';

Colledge, 'Epistola', p. 35./

Adam Easton presented to Pope Urban VI his

magnum opus, the Defensorium Ecclesiastice Potestatis,

'The Defense of Ecclesiastical Power', based on Dionysian

hierarchies, /* Dante Alighieri

in a fresco painted by Andrea del Castagno for the Cenacolo of

Sant'Apollinare, Florence./ and

for which he read - and countered - Dante Alighieri .

It ends with the Augustinian, 'Thou

hast created us for Thyself, O Lord, and our hearts can find

no rest, until they rest in Thee',

a passage Julian uses in the Westminster and subsequent Showings

(W75-75v,P10,A99v-100). In that same year Alfonso of Jaén

wrote the Epistola Solitarii,

in defence of Birgitta's visions, and he edited her entire Revelationes, in preparation for

her canonization. The material of Alfonso of Jaén's Epistola

Solitarii on the discernment of spirits is found in William Flete 's pre-1379 Remedies

Against Tempations; in the Cloud

Author 's treatises on Discernment of Spirits; in the

treatise on Catherine of Siena found in East Anglian Cloud

manuscripts;/49

/49.

Oxford, University College 14, ' doctrine schewyd of god to

seynt Kateryne of seen. Of tokynes to knowe vysytacions bodyly

or goostly vysyons whedyr thei come of god or of the feende ', East

Anglian manuscript; British Library, MS Royal 17 D v, ' Here

folowen dyuerse doctrynys deuowte and fruytfulle taken oute of

the lyfe of that glorious virgyn and spowse of our Lorde Seynt

Kateryne of Seenys './

in Adam Easton's 1390 Defensorium Sanctae

Birgittae; in the Chastising

of God's Children ;/50

/50. The

Chastising of God's Children, ed. Joyce Bazire and Eric

Colledge (Oxford: Blackwell, 1957), uses William Flete , Jan van Ruusbroec , Alfonso de Jaén,

and significantly adds an interpolation to Ruusbroec's text of

'Cardinals', p. 35/ in Julian's 1413 Showing

(A114v,115); and in Julian's conversation with Margery Kempe (M21)./50. British

Library, Add. 61,823, fols. 21-21v; The Book of Margery Kempe,

EETS 212, pp. 42-43. Among the materials is Alfonso's statement

that writings by visionary women be examined by literate men of

the Church. It is likely that the writings of all three women,

Birgitta, Catherine and Julian, received that examination - and

approbation. The Sloane Manuscripts give such a a statement as

colophon, echoing that found in the Cloud of Unknowing

and in Marguerite Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls./ A

manuscript of the Chastising, which had been at Sheen or

Syon, was noted as uniquely attributed to Walter Hilton in the

Schøyen collection at http://www.nb.no/baser/schoyen/5/5.13/index.html,

a link which no longer functions.

The Epistola solitarii also exists

translated into Middle English in a Norfolk manuscript of

Birgitta's Revelationes./51

/51.

Rosalynn Voaden, God's Words, Women's Voices: The

Discernment of Spirits in the Writing opf Late-Medieval Women

Visionaries (York: York Medieval Press, 1999), and 'The

Middle English Epistola Solitarii ad Reges of Alfonso of

Jaén: An Edition of the Text in British Library MS. Cotton

Julius F ii', Studies in St Birgitta, ed. Hogg,

I.142-179. The Norfolk manuscript in question also includes Magister Mathias' Prologue , and

much of the Revelationes. Hope Emily Allen had earlier

hoped to publish it. Of interest is that Syon manuscripts in

English, such as the Princeton University Garrett Revelations,

use the Swedish form in English 'Birgitte ', while