JOHN WHITERIG, O.S.B., HERMIT OF FARNE

The Ruins of Lindisfarne

♫

here are

strong similarities between the contemplations of an

Oxford-educated Benedictine, likely named John Whiterig, who

had become a hermit on to the Island of Farne, 1363, dying

there in 1371, and Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love

. When a student at Durham College (for he mentions being

saved from drowning in Oxford's Cherwell River), he would

have overlapped with Adam Easton, a student at Gloucester

College, both colleges established for educating young

Benedictines at Oxford. The Durham Benedictines first

settled at Wearmouth and Jarrow in memory of St Benet Biscop

and St Bede, then were invited in 1083 to Durham where they

served at the shrine of St Cuthbert, who had died on Farne

in 687. St Godric (mentioned in Richard

Methley's Epistle to Hew Heremyte) )visited St

Cuthbert's cell on Farne before becoming himself a hermit at

Finchale (1065-1170). Lindisfarne, at some distance from the

island of Farne, also continued as a monastic site until the

Reformation, though like Whitby with gaps following Viking

arrivals. Durham typically kept two monks on Farne, where

they supported themselves by fishing and lived intense lives

of prayer.

here are

strong similarities between the contemplations of an

Oxford-educated Benedictine, likely named John Whiterig, who

had become a hermit on to the Island of Farne, 1363, dying

there in 1371, and Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love

. When a student at Durham College (for he mentions being

saved from drowning in Oxford's Cherwell River), he would

have overlapped with Adam Easton, a student at Gloucester

College, both colleges established for educating young

Benedictines at Oxford. The Durham Benedictines first

settled at Wearmouth and Jarrow in memory of St Benet Biscop

and St Bede, then were invited in 1083 to Durham where they

served at the shrine of St Cuthbert, who had died on Farne

in 687. St Godric (mentioned in Richard

Methley's Epistle to Hew Heremyte) )visited St

Cuthbert's cell on Farne before becoming himself a hermit at

Finchale (1065-1170). Lindisfarne, at some distance from the

island of Farne, also continued as a monastic site until the

Reformation, though like Whitby with gaps following Viking

arrivals. Durham typically kept two monks on Farne, where

they supported themselves by fishing and lived intense lives

of prayer.

In the following, the Latin text derives from 'The Meditations of the Monk of Farne', ed. David Hugh Farmer, O.S.B., Studia Anselmiana 41 (1957), 141-245; the English translation from Christ Crucified and Other Meditations, ed. David Hugh Farmer, Trans. Dame Frideswide Sandemen, O.S.B. (Leominster: Gracewing, 1994). The complete paperback book is available: UK, ISBN 0 85244 266 1; USA, ISBN 0 87061 202 6. Dame Frideswide Sandeman well represents the continuing tradition of Julian's association amongst contemplatives, for she is a Benedictine at Stanbrook Abbey, which was founded from Cambrai, where exiled English nuns, including several descendants of St Thomas More , under the guidance of Dom Augustine Baker , O.S.B., had studied, copied and contemplated upon such texts, including Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love, eventually preparing it for publication in 1670, with Dom Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., as ostensible editor. Benedictinism is about Eternity, more than time, a contemplative choral dialogue of men and women across centuries. P. Franklin Chambers drew attention to the similarities between the two contemplative writers, John Whiterig and Julian of Norwich, in his Juliana of Norwich: An Introductory Appreciation and an Interpretative Anthology (London: Gollancz, 1955). The manuscript transcribed is Durham B.iv.34, fols. 5v-75, and which is the only extant manuscript with this text.

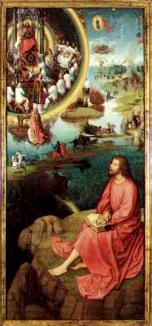

David Hugh Farmer mentions the self-identification of the Hermit of Farne with St John the Evangelist on the Isle of Patmos, to whom he addresses a 'Meditacio Eiusdem ad Beatum Iohannem Ewangelistam'.

Hans Memling, 'St John Writing Revelation,' St

John's Museum, Bruges

Reproduced with permission,

Memlingmuseum, Stedelijke Musea, Brugge, Belgium

John Whiterig, while Hermit on Farne, also began to write a poem in praise of St Cuthbert, perhaps dying before it could be finished.

Parallel

passages in Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love will be

added more completely at a later date, noted here with 'Julian '. My profound thanks to Catherina Lindgren,

Sweden, and to Iain Bruce, Oxford, for making these texts

available. The passages that follow can be read by both

contemplatives and scholars, and perhaps contemplatives and

scholars could even change places with each other to the

profit of both modes of thought and of being.

AD CRUCIFIXSUM

MEDITACIONES CUIUSDAM MONACHI APUD FARNELAND QUONDAM SOLITARII

tudy then, mortal, to know

Christ: to learn your Saviour. His body hanging on the

cross, is a book, opened before your eyes. The words of this

book are Christ's actions. as well as his suffering and

passion, for everything that he did serves for our

instruction. His wounds are the letters or characters, the

five chief wounds being the five vowels and the others the

consonants of your book . . .

tudy then, mortal, to know

Christ: to learn your Saviour. His body hanging on the

cross, is a book, opened before your eyes. The words of this

book are Christ's actions. as well as his suffering and

passion, for everything that he did serves for our

instruction. His wounds are the letters or characters, the

five chief wounds being the five vowels and the others the

consonants of your book . . .However much else you may know, if you do not know this, I count all your learning for naught, because without knowledge of this book, both general and particular, it is impossible for you to be saved. So eat this book which in your mouth and understanding shall be sweet, but which will make your belly bitter, that is to say your memory, because he that increases knowledge increases sorrow too.

May this book never depart from my hands, O Lord, but let the law of the Lord be ever in my mouth, that I may know what is acceptable in thy sight.

isce ergo homo Christum,

cognosce Saluatorem tuum, corpus etenim eius pendens in

cruce uolumen expansum est coram oculis tuis; uerba uolumina

huius sunt actus Christi, dolores et passiones eius. Omnis

enim Christi accio nostra est instruccio, litere seu

carateres uoluminis huius vulnera eius sunt, quorum quinque

plage quinque sunt uocales, cetere uero consonantes libri

tui . . .

Quidquid scis, si hoc nescis, nichil reputo quod scis; quia sine sciencia huius libri uniuersali uel particulari inpossibile est te saluari. Comede ergo uolumen hoc, quod dulce erit in ore tuo et intelectu, sed amaricabit uentrem tuum, id est memoriam, quia qui addit scienciam addit et dolorem . . .

Non recedat, Domine, liber uoluminis huius de manibus meis, sed ut lex Domini iugiter sit in ore meo, ut sciam quid acceptum sit in oculis tuis.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 53, fols. 29v-30

__________

'Thy body, sweet Jesus, is like a book all written with red ink ; so is thy body all written with red wounds . . . grant me to read upon thy book, and somewhat to understand the sweetness of that writing and to have liking in studious abiding of that reading'

'More yit, swet Jhesu, thy body is lyke a boke written al with rede ynke ; so is thy body al written with rede woundes . Now, swete Jhesu, graunt me to rede upon thy boke, and somwhate to undrestond the swetnes of that writynge, and to have likynge in studious abydynge of that redynge. And yeve me grace to conceyve somwhate of the perles love of Jhesu Crist, and to lerne by that ensample to love God agaynwarde as I shold. And, swete Jhesu, graunt me this study in euche tyde of the day, and let me upon this boke study at my matyns and hours and evynsonge and complyne, and evyre to be my meditacion, my speche, and my dalyaunce.'

Richard Rolle, Meditations on the Passion

Vowels are the soul, consonants the bones and flesh of words.

Spinoza on Hebrew

On Jesus shadowed in Isaac:

Thou art Isaac, who didst make laughter for us by offering thyself to God in sacrifice upon a mount called Calvary. Thou art the ram, caught by the horns amidst the briers, and sacrificed in place of the son; for that which thou hadst assumed succumbed to death, but thou who didst assume it couldst not succumb. And yet thou art not two but one; according to thy human nature thou didst die and wast buried, according to thy divinity thou didst remain unhurt. And thus, O good Jesus, thou didst make laughter for us amidst tears and music for us in thine own lament.

Fourteenth-Century Icelandic Manuscript, Bible in Icelandic, Abraham sacrificing Abraham, stopped by angel grabbing his sword, ram caught by horns in thicket. Árni Magnússon Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland.

u es Isaac, qui risum nobis

fecisti, quando te ipsum tradidisti sacrificium Deo super

unum moncium qui Calvarie dicitur. Tu es ille aries inter

uepres herens cornibus, qui pro filio immolatur: quia quod

assumpsisti morti succubuit, sed qui assumpsisti morti

succumbere non potuisti; et non duo tamen sed unus, qui

secundum humanum naturam mortuus es et sepultus, et secundum

Diuinam mansisti illesus. Risum igitur, bone Ihesu, nobis in

lacrimis suscitasti, et musicam in luctu tuo.

u es Isaac, qui risum nobis

fecisti, quando te ipsum tradidisti sacrificium Deo super

unum moncium qui Calvarie dicitur. Tu es ille aries inter

uepres herens cornibus, qui pro filio immolatur: quia quod

assumpsisti morti succubuit, sed qui assumpsisti morti

succumbere non potuisti; et non duo tamen sed unus, qui

secundum humanum naturam mortuus es et sepultus, et secundum

Diuinam mansisti illesus. Risum igitur, bone Ihesu, nobis in

lacrimis suscitasti, et musicam in luctu tuo.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 2, fol. 7

Julian on Christ and

laughter

On Jesus shadowed in Jacob

Thou hast beguiled the devil, through whose envy death entered into the world; and this thou didst do so wisely and fittingly, that life rose up from thence whence death had sprung, and he, who by a tree had gained his victory, was likewise by a tree overcome.

. . . delusisti diabolo, cuius inuidia more introiuit in orbem terrarum: et tam prudenter hoc fecisti et conuenienter, ut unde mors oriebatur inde uita resurgeret, et qui in ligno uicerat per lignum quoque uinceretur.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 3, fol. 7

On Jesus shadowed in Joseph

Thou shalt no longer be called Jacob, Lord, but Joseph shall be thy name, which is interpreted 'increase' or 'joining'. Either meaning is more fitting, because thou hast increased thy people exceedingly, and thou wast thyself joined to us, when the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, that that man could in very truth say unto thee: 'This is now bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh'.

on vocaberis ultra Domine

Iacob, sed Ioseph erit nomen tuum, quod augmentum siue

apposicio interpretatur; qui utraque nominis interpretacio

optime tibi conuenit, siue quia auxisti populum tuum

uehementer, siue quia appositus es nobis quando Verbum caro

factum est et habitauit in nobis, ita ut dicere ueraciter

poterit homo tibi: Hoc nunc os ex ossibus meis, et caro de

carne mea.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 3, fol. 7v

Remember us then, O Lord, when it shall be well with thee, for thou art our brother and our flesh; suggest to the Father that he should fill the sacks of thy brethren - fill them, I mean, with that wheat which, once it had fallen into the ground and died, brought forth much fruit, and filled every living creature with blessing. Thou who knowest no ill-will towards thy brethren, grant us our measure of wheat. For we have no other advocate who has been made unto us justice and sanctification, and whom the Father always hears for his reverence, but thee, good Lord, who art the propitiation for our sins. Remember then, O Lord, when thou standest in the sight of God, to speak well on our behalf. Ask thy Father to give me that wheat which with desire I have desired to eat before I die.

emento nostri ergo, Domine,

dum bene tibi fuerit, quia caro et frater noster es, ut

suggeras Patri two quatinus impleantur sacci fratrum tuorum

illo dico frumento, quod dum semel cadens in terra mortuum

fuit, multum fructum attulit et omne animal benediccione

repleuit. Qui igitur nescis inuidere fratribus illius,

tritici mensuram impertire nobis. Non enim alium habemus

Aduocatum, qui nobis factus est iusticia et sanctificacio,

quem semper audit Pater propter suam reuerenciam, quam te,

bone Domine; et tu propiciacio es pro peccatis nostris.

Recordare ergo, Domine, dum steteris in conspectu Dei, ut

loquaris pro nobis bonum. Postula Patrem tuum ut michi donet

triticum, quod desiderio desideraui manducare antequam

morior.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 4, fol. 8

Julian on Christ as our

brother

I wish for no other wheat but thee: give me thyself, and the rest take for thyself. For what have I in heaven, and what have I desired more than thee on earth? Whatever there is besides thee does not satisfy me without thee, nor hast thou any gift to bestow which I desire so much as thee. If therefore thou hast a mind to satisfy my desire with good things, give me nought but thyself. For my desire would not be pleasing in thy sight, if I longed for something other than thee more than thee.

liud nolo triticum nisi

temetipsum: da michi ergo teipsum, et cetere tolle tibi.

Quid enim michi est in celo, et quid plus quam te optaui

super terram? Certe quicquid est preter te non michi

sufficit preter te, nec est munus apud te quod tantum

desidero sicut te. Si ergo uelis replere in bonis desiderium

meum, nichil aliud michi des nisi temetipsum. Non enim coram

te cupiditas mea placeret si aliquid aliud, quod tu non es,

plus quam te optaret.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 5, fol. 8

od for your goodness give to

me yourself. For you are enough to me. And I may ask nothing

that is less, that may be full worthy of you. And if I ask

anything that is less, ever I shall want, but only in you I

have all. And these words 'God of your goodness' are very

lovely to the soul and very close to touching our Lord's

will. For his goodness comprehends all . . .

Julian of Norwich,

Prayer, Showing of Love, Westminster Manuscript

On Jesus Shadowed in Moses

Thou art the brazen serpent hung upon the gibbet, a remedy to all believers against the bites of the devil. Thou art the lonely sparrow upon a house-top, and thou hast found a nest for thyself which is the Virgin's womb. Thou art the scapegoat, and hast carried our sins into the wilderness of eternal oblivion, so that as far as the east is from the west, so far should our iniquities be from us. Thou art the lamb of God who takest away the sins of the world . . .

u es ille serpens eneus

suspensus in patibulo, in quem credentes curantur

omnes a morsu diabolico. Tu es enim ille passer in tecto

solitarius, et nidum tibi inuenisti, qui Virginis est

uterus. Tu es hircus emissarius, qui peccata nostra tulisti

in desertum obliuionis perpetue, ut quantum distat ortus ab

Occidente longe fierent a nobis iniquitates nostre. Tu es

agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi . . .

u es ille serpens eneus

suspensus in patibulo, in quem credentes curantur

omnes a morsu diabolico. Tu es enim ille passer in tecto

solitarius, et nidum tibi inuenisti, qui Virginis est

uterus. Tu es hircus emissarius, qui peccata nostra tulisti

in desertum obliuionis perpetue, ut quantum distat ortus ab

Occidente longe fierent a nobis iniquitates nostre. Tu es

agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 6, fol. 8v

. . . all things work together for good; not only good works, but even sins. For example, one of the elect who is somwhat elated on account of an outstanding virtue is tempted by the devil to impurity and allowed to fall, so that the memory of so shameful a sin may for the future preserve him from pride, and give him rather, what is safer, a fellow-feeling for the lowly.

. . . omnia cooperantur in bonum, hiis qui secundum propositum uocati sunt sancti, non tantum bona opera sed eciam peccata. Verbi gracia: aliquis electus a diabolo temptatur per luxuriam, qui ex aliqua uirtute qua forte pollet aliqualem habet elacionem, permittitur cadere, ut quam uile se meminerit flagicium perpetrasse: de cetero numquam habeat materiam superbie, immo, quod est tucius, humilibus consentire.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 9, fol. 10

Julian, 'All Shall Be

Well'

On Jesus Shadowed in Jonathan

Let us by no means bring to naught in our city the likeness of those whom we have made to our own image and likeness, but rather let thy wisdom prevail over the malice into which they have falled through their proud self-love, desiring to become like gods, knowing good and evil. Let it reach from thee, the end, for thou are both beginning and end, unto the end of all creation, that is to say man, who was created last of all, and let it dispose all things sweetly.

uos ad ymaginem et

similitudinem nostram fecimus, eorum ymaginem in ciuitate

nostra nullo modo ad nichilum redigamus; sed pocius uincat

sapiencia tua maliciam eorum, in quam proprie superbiendo

impegerunt, cupientes fore sicut dii, scientes bonum et

malum. Attingat ergo a te fine, qui principium es et finis,

usque ad finem tocius creature, hominem uidelicet qui ultimo

creatus est, et disponat omnia suauiter.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 11, fol. 11

Julian, on God in the

City of the Soul, on Wisdom

Thou art Christ, Son of the living God, who in obedience to the Father hast saved the world.

u es Cristus Filius Dei uiui,

qui precepto Patris mundum saluasti.

u es Cristus Filius Dei uiui,

qui precepto Patris mundum saluasti.

Despenser Retable, Norwich Castle, Contemporary with Julian

I see thee, O good Jesus, nailed to the cross, crowned with thorns, given gall to drink, pierced with the lance, and for my sake . . . upon the gibbet of the cross.

uideo te, Ihesu bone, cruci conclauatum, spinis coronatum, felle potatum, lancea perforatum, et omnibus membris super crucis patibulum propter me diuaricatum.

. . . being thyself most beautiful, for me thou hast desired to be accounted as a leper and the last of men;

. . . cum speciosus sis, ut leprosus et uirorum nouissimus pr me reputari uoluisti;

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 13, fols. 11v-12v

In thy head I perceive wondrous multiplicity of suffering, for in all thy five senses thou didst feel indescribable Pain. Thou didst see thyself crucified and hanging between thieves, thy friends deserting thee, thine enemies gathering round, thy mother weeping, and the corpses of condemned criminals strewn round about; whatever met thy gaze was a source of pain and sorrow, of horror and dismay.

n capite tuo admirabilem

penarum intueor multitudinem, quia per omnia organa quinque

sensuum inena rrabilem sensisti dolorem. Te ipsum enim

uidisti crucifixsum atque pendentem in medio latronum,

amicos uidisti fugere, inimicos appropinquare, matrem

uidisti flere, atque cadauera dampnatorum in circuitu

iacere, et quicquid uisu traxisti pena fuit et dolor, tremor

et horror.

n capite tuo admirabilem

penarum intueor multitudinem, quia per omnia organa quinque

sensuum inena rrabilem sensisti dolorem. Te ipsum enim

uidisti crucifixsum atque pendentem in medio latronum,

amicos uidisti fugere, inimicos appropinquare, matrem

uidisti flere, atque cadauera dampnatorum in circuitu

iacere, et quicquid uisu traxisti pena fuit et dolor, tremor

et horror.

Thou didst hear threats, murmuring, sarcasm and taunts from the bystanders; threats, when they cried out: 'Away with him, away with him; crucify him'; murmuring, when they said: 'He saved others, himself he cannot save', and some had said before that: 'He is good', while others said: 'No, he seduceth the multitude'. Sarcasm, when the soldiers, being their knees, greeted thee with: 'Hail, king of the Jews'; for sarcasm is a covert sort of mockery, when one is ironically called something by the scoffer, other than what he believes to be true. They believed him indeed to be a criminal rather than the king of the Jews, and yet they spoke the truth although with false intent. Thou didst hear taunts, when they said: 'Vah! Thou who dost destroy the Temple and in three days rebuild it!'

udisti timorem et susurrium,

subsannacionem et derisum ab hiis qui in circuitu stabant.

Timorem, inquam, audisti quando dixerunt: Tolle, tolle,

crucifige eum. Sussurium audisti quando dixerunt: Alios

saluos fecit, seipsum non potest saluum facere, et ante

quidam dixerunt quia bonus est, alii autem non, sed seducit

turbas. Subsannacionem tunc audisti quando geniculantes

dicebant Aue rex Iudeorum, quia subsannacio oculta est

derisio, cum aliud uidelicet aliquis uocatur ironice quam a

deridente fore creditur. Credebant enim eum pocius maleficum

quam regem Iudaeorum, et tamen uerum dicebant quamuia

menciendo. Audisti, Domine, derisum quando dicebant: Vah qui

destruit templum et in tribus diebus reedificat.

Thou didst taste bitterness, O Lord, when they gave thee gall for thy food, and in thy thirst gave thee vinegar to drink. Thy nostrils, O Lord, breathed in the stench of the corrupting corpses of executed criminals lying round about. Thy sense of touch felt fierce pain in thy head, for the crown of thorns pierced it so grievously that thy blood flowed down in torrents through thy hair even to the ground. And so, good Lord, whatever thou didst look upon was terrible, whatever thou didst hear was horrible, whatever thou didst taste was bitter, whatever thou didst smell was putrid, and whatever thou didst touch was painful.

ustasti Domine amarum, quando

in escam tuam dederunt fel et in siti tua potauerunt te

aceto. Per nares, domine, traxisti fetorem ex cadaueribus

putridis morte punitorum, que in circuitu iacebant. Per

tactum uero in capite sensisti asperitatem, quia corona

spinarum in tantum pungebat capud tuum ut cruorem habunde

per crines in terram currere faceret. Bone ergo Domine,

quicquid uidisti fuit terribile, quicquid audisti fuit

horribile, quicquid gustasti fuit amarum, quicquid odorasti

fuerat fetidum, et quicquid tetigisti fuit ualde asperum.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 14, fols. 12-12v

One thing, O good Jesus, I would know of thee; namely what reward will be bestowed on thee for all that thou hast suffered for us, since we have nothing that we have not received from thee. All gold is but as a grain of sand in thy sight, and silver would be accounted as mud in compensation for thy passion.

num a te, Ihesu bone, scire

uellem, qua uidelicet mercede donaberis pro hiis que passus

es pro nobis, cum nos nichil habeamus nisi quod a te

accepimus. Omne enim aurum in conspectu tuo arena est

exigua, et tamquam lutum estimabitur argentum in

recompensacione tue passionis.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 15, fol. 12v

Julian on Passion

Speak, Lord, for thy servants listen, ready to receive the engrafted word which is able to save their souls. If thou desirest to know this plainly, call thy husband, that thou mayest understand aright. Let him who hath ears to hear, hear what Christ saith now to the churches.

oquere, Domine, quia audiunt

serui tui, parati suscipere institum uerbum quod potest

saluare animas eorum. Si hoc aperte scire desideras, uoca

uirum tuum ut recte inteligas. Qui ergo habet aures

audiendi, audiat quid modo ecclesiis Christus dicat.

oquere, Domine, quia audiunt

serui tui, parati suscipere institum uerbum quod potest

saluare animas eorum. Si hoc aperte scire desideras, uoca

uirum tuum ut recte inteligas. Qui ergo habet aures

audiendi, audiat quid modo ecclesiis Christus dicat.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 16, fols. 13-13v

I know well, O Lord, that thou desirest my whole self when thou askest for my heart, and I seek thy whole self when I beg for thee.

cio Domine, scio, totum me

cupis cum cor meum petis, et totum te desidero cum te ipsum

postulo.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 18, fols. 13v-14

Julian's Prayer

. . . even if he at times out of his goodness enters under our roof to abide with us. This he does especially according to that operation whereby he enables us to taste the first-fruits of the Spirit, by breaking for us a little of the bread which is himself, and saying: 'Taste and see that the Lord is sweet'.

. . . et si aliquando propter suam bonitatem intret sub tectum nostrum ut maneat nobiscum, secundum illam maxime operacionem qua nos facit probare de primiciis Spiritus frangens nobis modicum de pane seipso et dicens: Gustate et uidete quoniam suauis est Dominus.

Julian

Thou canst, O good Jesus, most clearly be recognized in the breaking of this bread, which no one else breaks as thou dost. For thou dost visit the soul with such joy, and fill it with such ineffable delight and indescribable love, that for one who loves such favours the enjoyment of so gracious a visit from such a guest, were it only for the space of a day, would surpass all physical love and a whole world full of riches. This is not surprising, since it is a sort of beginning of eternal joys, a sign of divine predestination and pledge of eternal salvation; it is a grace rendering us pleasing to God, and bestows on us a new name, which no one knows save he who receives it, and apart from the sons and daughters of God none can have a share in it.

iquidissime, Ihesu bone,

cognosci poteris in fraccione panis, quem nemo alius sic

frangit sicut tu. Quam enim sic uisitas animam iubilo, et

ineffabili uoluptate ac inenarrabili reples amore, ut

delicias amanti delectabilius foret tanti hospitis tam

iocunda frui uisitacione, saltem per diei medium, super

omnem amorem mulierum et totum orbem terrarum diuiciis

repletum. Nec mirum cum sit de eternis gaudiis inicium

aliquod, argumentum Diuine predestinacionis, et arra salutis

perpetue, gratia gratum faciens et nomen nouum, quod non

nouit quis nisi qui accipit, cui non communicat alienus a

filiis Dei et filiabus.

iquidissime, Ihesu bone,

cognosci poteris in fraccione panis, quem nemo alius sic

frangit sicut tu. Quam enim sic uisitas animam iubilo, et

ineffabili uoluptate ac inenarrabili reples amore, ut

delicias amanti delectabilius foret tanti hospitis tam

iocunda frui uisitacione, saltem per diei medium, super

omnem amorem mulierum et totum orbem terrarum diuiciis

repletum. Nec mirum cum sit de eternis gaudiis inicium

aliquod, argumentum Diuine predestinacionis, et arra salutis

perpetue, gratia gratum faciens et nomen nouum, quod non

nouit quis nisi qui accipit, cui non communicat alienus a

filiis Dei et filiabus.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 20, fol. 14v

here may no man entere the

sayde exercyse be cunnynge

here may no man entere the

sayde exercyse be cunnynge

ffor

contemplatyfe

lyfe

may nought be taught oone be anothere

bot

where

as

god whiche es verrey trowthe manyfestys hym

selfe

in

spirit.

ther all necessaries moste plentevously are lerned

and

that

is

that the spirit says in the Apochalips vincenti

says

he

schalle

gyffe hym a litil white stone and in it a newe

name

the

whiche

no man knowes but who that takys it. This

litel

stone

promysed

to a victorious man it is called. Calcalus.

for

the

litelnes

ther of. ffor yyf alle a man trede it with his fete

yit

he

is

not hurte th er with. This stone it is red with a schyny

nge

witness

to

the lykenesse of a flawme of fyre. litylle and

rownde

and

be

the serkle ther of it is playne and smothe. Be this

litel

stone

we

vndyrstande oure lorde ihesu cryste. whyche by

his

dyuynyte

is

the whitnesse of euer lastande lyght and the

schynere

of

the

ioye of god. Also the myrroure withoute spotte

in

the

whiche

alle thynge hase lyfe. Whosumeuere therefore

[A118]

For God hateth none of those things which he has made.

uia Deus nichil odit eorum que

fecit.

Julian

The Will of God is independent of any cause, since it is itself the first cause of all things, visible and invisible, which the Creator has made.

. . . cuius uoluntatis non est causa cum sit ipsa prima causa uisibilium omnium et inuisibilium a Creatore conditorum .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 22, fols. 15-15v

Moreover he created all other beings to serve you, desiring that nothing should be superior to you save himself alone, and in order to show you still further the exceeding greatness of his kindness and condescension, he emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, and was found in appearance just like other men. He who in the beginning created heaven and earth, was afterwards seen upon the earth, and conversed with men for thirty-two years and three months. Even this would not satisfy him, but he must needs be put to death in the cruellest and most shameful way for the salvation of your soul.

niuersam insuper creaturam tui

in obsequium creauit, et te superius nichil esse uoluit,

ipso solo excepto qui ut nimietatem bonitatis et humilitatis

sue adhuc tibi demonstraret semetipsum exinaniuit formam

serui accipiendo, et habitu inuentus est homo; atque qui in

principio creauit celum et terram, postea in terra uisus est

et cum hominibus conuersatus est triginta et duobus annis ac

tribus mensibus. Nec hoc sibi suffecit, nisi morte

turpissima crudelissime occideretur pro salute anime tue.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 24, fols. 16-16v

Julian, Lord and Servant

Why love gold more than God, silver more than Christ, vanity more than Trinity, the creature more than the Creator? Do you think he who formed the ear does not hear, or that he who fashioned the eye is not watching what you do? Do you suppose that, although he is silent now and holds his peace, he will not speak out like one in labour?

ur aurum plus diligis quam

Deum, argentum quam Christum, uanitatem quam Trinitatem,

creaturam quam Creatorem? Putasne quia qui plantauit aurem

non audit, aut qui finxit oculum non considerat que tu

facis? Putas etsi tacet nunc atque silet, quod non sicut

parturiens loquetur?

. . . If you ascend into heaven, there you will find him whom you flee; if you descend into hell, he is there; if you take the wings in the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even thence will his hand retrieve you . . .

quia si in celum ascenderes, illic quem fugis reperies, si descenderis in infernum adest, si sumpseris pennas tuas diluculo et habitaueris in extremis maris, etenim illinc manus eius educet te . . .

Julian on the Deep Sea Bed, using this Psalm

I fix my inward gaze upon the circle of the divine life, and behold my own nature so united to God in personal union, that we should think it not robbery to be equal with God, whose good pleasure it is to dwell in him bodily according to the whole fullness of the Godhead; when I see flesh and blood sitting upon the throne of the Trinity, how greatly do I then rejoice in his glory and exult in God my Jesus! . . . Which of the angels would dare to say to him: 'Thou art my brother as well as my God'? Not one of them. It is enough for them to adore the man Christ, their Lord and ours.

. . . cum oculos mentis in orbem fixero Diuinitatis, et naturam meam uidero coniunctam esse Deo in unitatem persona, ita ut rapinam non arbitretur homo esse se equalem Deo, cui beneplacitum sit habitare in eo secundum omnem plenitudinem diuinitatis corporaliter, carnem et sanguinem sedere in trono Trinitatis; quantum tunc credis eius glorie congaudebo et exultabo in Deo Ihesu meo, quia quicquid sibi uidero concessum, totum illud michi reputabo factum, qui licet Deus sit cuius nature non sum, idem tamen est homo cuius nature sum et ego. Quis hoc et audeat dicere angelorum: 'tu es enim frater meus ipse qui et Deus meus?' Certe nullus. Sufficet eis adorare hominem Christum Dominum suum atque nostrum.

Julian on on the 'eye of the mind', on Christ our Brother, us his throne

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 23, fols. 16v-17

As for that sin of which we are speaking, namely the sin against the Holy Ghost, which the Truth says shall be forgiven neither here nor hereafter, I would say that Christ declares that it is not forgiven here, not because it cannot be forgiven here, if anyone repents of it before death and begs pardon; but it is said not to be forgiven here, because seldom or never is forgiveness for it sought . . .

unc ad hoc de quo loquimur

peccato uidelicet in Spiritum Sanctum, quod Veritas dicit

nec hic remitti neque in futuro, dico non ideo dicit

Christus illud hic non remittitur quod non possit hic

remitti, si de eo penituit quis ante mortem et ueniam

petierit; sed ideo dicitur quod hic non remittetur

quia uix uel numquam pro eo uenia postulatur: sic enim

solebant homines dicere: ideo non habuit quia non petiuit.

unc ad hoc de quo loquimur

peccato uidelicet in Spiritum Sanctum, quod Veritas dicit

nec hic remitti neque in futuro, dico non ideo dicit

Christus illud hic non remittitur quod non possit hic

remitti, si de eo penituit quis ante mortem et ueniam

petierit; sed ideo dicitur quod hic non remittetur

quia uix uel numquam pro eo uenia postulatur: sic enim

solebant homines dicere: ideo non habuit quia non petiuit.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 30, fol. 19v

Would that my longing might imprint its own characters on the hearts of them that hear, just as the hand that writes presents them to the eyes of the readers; but this belongs to the Trinity alone, the husbandman; for neither is he anything who plants, nor he who waters, but God who gives the increase.

tinam haberet affectus

caracteres suos in cordibus audiencium, quales tradit manus

scribens ad oculos hec legencium; sed quia hoc soli conuenit

Agricole Trinitati, quoniam neque qui plantat est aliquid,

neque qui rigat, sed qui incrementum dat Deus.

Thus David is wont to emply the past tense, in for instance: 'they gave me gall for my food' and other similar passages which, as no one doubts, were spoken of Christ.

inc familiare est Dauid uerbis

uti de preterito sicuti est illud: 'dederunt in escam meam

fel', et cetera his similia, que de Christo fuisse dicta

nullus est qui ambigat.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 38, fols. 22-22v

Julian and Adam Easton, from Rabbi David Kimhi, discussing Psalm of David

'All day long I stretch out my hands on the cross towards thee, O man, to embrace thee, I bow my head to kiss thee when I have embraced thee, I open my side to draw thee into my heart after this kiss, that we may be two in one flesh.

ota die expando in cruce manus

meas ad te homo ut te amplexer, capud meum inclino ut

amplexatum deosculer, latus meum aperio ut osculatum

introducam ad cor meum, et simus duo in carne una.

ota die expando in cruce manus

meas ad te homo ut te amplexer, capud meum inclino ut

amplexatum deosculer, latus meum aperio ut osculatum

introducam ad cor meum, et simus duo in carne una.

Julian on side wound

Lo, he offers us embraces and kisses who by a mere word created the universe.

n profert nobis amplexus et

oscula, qui solo sermone creauit uniuersa.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 39, fol. 23

Even so is it with mothers who love their little children tenderly; if these happen to be at a distance from them, and want to run to them quickly, they are wont to stretch out their arms and bend down their heads. Then the little ones, taught in a natural way by this gesture, run and throw themselves into their mothers' arms . . .

ic denique solent matres

filiolos suos tenere diligentes, si forte distantes ad se

eos cicius uellent currere, brachia statim expandere, capud

inclinare, quo signo paruuli naturaliter edocti ad oscula

festinant, atque currentes matrum ruunt in amplexus . . .

Christ our Lord does the same with us. He stretches out his hands to embrace us, bows down his head to kiss us, and opens his side to give us such; and though it is blood which he offers us to such, we believe that it is health-giving and sweeter than honey and the honey-comb.

ta et nobiscum facit Christus

Deus noster. Ad amplexandum uero nos manus expandit, ad

osculandum nos capud demittit, atque ad suggendum latus

nobis sperit; et licet sanguis sit quem propinat ad

suggendum, salutiferum tamen illum credimus et dulciorem

super mel et fauum.

ta et nobiscum facit Christus

Deus noster. Ad amplexandum uero nos manus expandit, ad

osculandum nos capud demittit, atque ad suggendum latus

nobis sperit; et licet sanguis sit quem propinat ad

suggendum, salutiferum tamen illum credimus et dulciorem

super mel et fauum.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 40, fol. 23

Anselm, Ancrene Wisse, Julian on Jesus as Mother

And to speak of how after kissing us he was to draw us into his body: there are indeed other sacraments which are means of drawing us into the mystical body of Christ, that is the Church, but the sacrament by which we believe it is brought about was especially set forth at the Last Supper, and he who instituted this same sacrament speaks thus: 'He who eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood abideth in me and I in him'.

qualiter post osculum

nos introduxerit in corpus suum, non obstantibus aliis

sacramentis per que in corpus Christi misticum quod Ecclesia

est introducimur, in cena Domini specialiter commendatum est

sacramentum per quod hoc fieri credimus, unde eiusdem

institutor sacramenti ita dicit: Qui manducat meam carnem et

bibit meum sanguinem, in me manet et ego in illo.

qualiter post osculum

nos introduxerit in corpus suum, non obstantibus aliis

sacramentis per que in corpus Christi misticum quod Ecclesia

est introducimur, in cena Domini specialiter commendatum est

sacramentum per quod hoc fieri credimus, unde eiusdem

institutor sacramenti ita dicit: Qui manducat meam carnem et

bibit meum sanguinem, in me manet et ego in illo.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 43, fol. 24v

Free from confusion because of their hope, they hasten to the embraces of the Saviour, for hope confoundeth not, and by charity they receive the kiss which the bride in the Canticle seeks when she says: 'Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth'.

. . . inconfuse per spem in amplexus ruunt Saluatoris quia spes non confundit, atque per caritatem osculum accipiunt quod petiuit sponsa in Canticis dicens: Osculetur me osculo oris sui.

What should we understand by the mouth of the Father but the Son, and what by the kiss of the mouth but the Holy Ghost? This kiss was solemnly imprinted on the mouth of the Church when the Holy Ghost came down in tongues of fire upon the Apostles, who may well be called the mouth of the Church, for their sound has gone forth into all the world and their words unto the uttermost ends of the earth. One of them, speaking of the bestowal of this kiss, says: 'The love of God is poured abroad in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who is given to us'. and again: 'God hath sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying: 'Abba, Father', and yet again: 'Whoever hath not the Spirit of Christ is none of his'.

uid per os Patris inteligere

debemus nisi Filium, et quid per osculum oris nisi Spiritum

Sanctum? Quod ori Ecclesiae solempniter tunc impressum fuit

quando super Apostolos in linguis igneis descendit Spiritus

Sanctus, qui bene os Ecclesie uocari possunt, quia in omnem

terram exiuit sonus eorum et in fines orbis terrae uerba

eorum. De huius osculi dono quidam eorum loquitur dicens:

Caritas Dei diffusa est in cordibus nostris per Spiritum

Sanctum qui datus est, et iterum: Missit Deus Spiritum Filii

sui in corda nostra clamantem: Abba, Pater, et iterum adhuc:

Qui Spiritum Christi non habet, hic non est eius.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 44, fols. 25-25v

What does it mean that those who have fled to Christ, and been embraced, kissed and drawn into his body, are suckled by him, to follow up the order of the aforesaid metaphor, and what precious gift do they receive from him? If I wished to speak the exact truth, I should say plainly that I do not know how to answer this. For all that, however, I will be no means hold my peace on this account, but like a blind man I will now set myself to tapping at it with my stick.

uid est quod isti ad Christum

fugientes amplexati, osculati, in corpus Christi introducti

de ipso sugunt, ut iuxta processum antedicti loquar signi,

uel quale iocale ab illo recipiunt? Si enim quod uerius est

uoluero dicere, dicam plene quod ad hoc nescio respondere.

Nichilominus propter hoc omnino non tacebo, sed uelud cecus

baculum ad hoc iactare nunc curabo.

To the question what they suck from him, I reply with the Scriptures: 'Honey from the rock' and sweetness from Christ. Only those who have actually experienced the sweet saviour of this rock know the sweetness, for it is a hidden manna, unknown to all who have not tasted it. [The text goes on to compare this sweetness to the pearl of great price, of the kingdom of heaven, for which the merchant gave up all else as dross.]

d hoc denique quod queritur

quid de ipso sugunt, respondeo cum Scriptura: mel de petra

et dulcedinem de Christo, quam quidem dulcedinem tantum hii

nouerunt qui dulcorum huius petre didicerunt, quia manna est

absconditum quod non nouit quis, nisi qui gustauit.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 45, fol. 25v

. . . quam Spiritum Sanctum qui Patris atque Filii connexio esse constat ac amor utriusque, unde scribitur: In Patre manet eternitas, in Filio equalitas, in Spiritu Sancto eternitatis equalitatisque connexio. Aliud ergo osculum, aliud Christi et Ecclesie uinculum nemo potest ponere preter id quod positum est, quod est Spiritus Sanctus qui nos transferet in eandem ymaginem ad quam facti sumus, secundum influenciam Ymaginis in ymaginem: Potencie in memoriam, Sapiencie in intellectum, Bonitatis uel Amoris in uoluntatem, quibus fit anima deiformus et similis Deo inter filios Dei . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 47, fols. 26v-27

Victorines, Abelard, Marguerite Porete, Dante and Julian on Power, Wisdom, Love

And Paul refers to the great sacrament of Christ and the Church the words that Adam spoke when he awoke from sleep, concerning himself and his wife. What words? The following: 'This is now bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, for which cause a man shall leave father and mother and cleave to his wife, and they shall be two in one flesh', and Truth speaking to us all in the person of the apostles, has commanded us saying: 'Abide in me'.

t hoc dicit Paulus magnum esse

sacramentum in Christo et Ecclesia quod post soporem dixit

Adam de se et uxore sua. Quid dixit? Certe hoc: nunc os ex

ossibus meis et caro de carne mea, propter quod relinquet

homo patrem et matrem et adherebit uxori sue, et erunt duo

in carne una; unde Veritas precipit omnibus nobis in

apostolis dicens: Manete in me . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 49, fol. 27v

. . . it is the greatest delight to me to suck the breasts of the king who has been my hope from the bosom of my mother, and upon whom I was cast from the womb. But I also need to enter again into the womb of my Lord, and be reborn into life eternal, if I am to be amongst the members of the Church whose names are in the book of life. For the Church must return thither whence she came forth, and to enter into her reward must be born again of him who first gave her birth . . .

. . . et delectabile nimium michi est mamillam regis suggere, qui spes michi est ab uberibus matris mee et in quem proiectus sum ex utero; sed et necessarium michi esse constat in uentrem Domini mei iterato introire et renasci in uitam eternam, si aliquis fuerim illius Ecclesie quorum nomina sunt in libro uite. Unde enim Ecclesia processit, necessarium habet iterum reuerti illuc atque per quem primo genita fuerat ad meritum, iterum per eundem nascatur ad premium.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 50, fol. 28

Julian on birth/death deliverance

So, precisely because I am a sinner, I have fled to thee; since there is nowhere I can flee from thee save to thee. Thou dost stretch out thine arms to receive me and bend down thy head to kiss me; thou dost bleed that I may have to drink, and open thy side in thy desire to draw me within.

uia ergo peccator sum, ad te

confugi; quoniam a te nisi ad te impossibile est me fugere.

Hinc manus expandis ut me suscipias, capud inclinas ut

osculum michi porrigas, sanguine cruentas ut me potes, latus

aperis ut te uelle introire me illuc insumes.

What shall then separate me from the love of Christ, and prevent me from casting myself into his embrace, when he stretches out his hands to me all day long.

uid ergo separabit me a

caritate Christi, ut non ruam in amplexus eius qui tota die

expandit ad me manus meas?

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 51, fol. 28v

That is why it is said that the dove in the clefts of the rock is the Church in the wounds of Christ, for just as Eve came forth from the side of her husband, so the Church, Christ's bride, came forth when the water and blood flowed from his pierced side.

oc est quod dicitur: Columba

mea in foraminibus petre Ecclesie in uulneribus Christi; de

latere enim Christi Ecclesia Christi, sponsa Christi, uelud

Eua de latere uiri sui egressa est, quando fluxit aqua cum

sanguine de latere lanceati.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 52, fol. 29

. . . for that was my petition. Merrily and with mild countenance thou didst call out in reply: 'Love, and thou shalt be saved'.

. . . quod et fuit peticio mea. Hillariter enim et uultu placido proclamando sic respondisti: Dilige et saluus eris.

This treasured visit of thine, O Lord, and thy salutary counsel do indeed compel me to love thee, but when I recall the gaiety and kindness with which thou didst utter these words, then does gladness truly fill my heart. For thou didst speak as though thou wert laughing.

ec tua, Domine, desiderabilis

uisitacio et ista salutifera doctrina te diligere me

compellunt, sed et protinus letus reddor cum reminiscor

hillaritatis et beneuolencie quibus hec uerba pronunciasti.

Quasi enim ridendo ista dicebas.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 55, fol. 30v

Julian and Christ as merry

It is not love of that sort [that which is merely not hated] which the Lord has chosen, but such as he wrote with his finger for Moses on the summit of Mount Sinai, for him to teach to the children of Israel using these words: 'Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart and with thy whole soul and with all thy strength. This is the first and greatest commandment'. Such is the love which I have chosen, saith the Lord.

on est ergo dileccio hec quam

elegit Dominus, sed est hec quam digito scripsit Dominus

Moysy in summitate montis Sinay, quam doceret filios Israel

et diceret ad eos: Diliges Dominum Deum tuum ex toto corde

tuo et ex toto anima tua et ex tota uirtute tua. Hoc est

primum et maximum mandatum. Talem dileccionem elegi, dicit

Dominus.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 57, fol. 31v

Julian and the Shema

For there are nine degrees of love which lead up to God, like Jacob's ladder reaching from earth to heaven. Three are comprised within the affections of the heart, three in the love of the soul, and three in the love of strength, that is of fortitude, as it is written: 'Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart'. which refers to the affections, 'with thy whole soul', which refers to spiritual love, and 'with all thy strength', which refers to the steadfast love of choice.

ouem enim gradus sunt diuini

amoris quibus ad Deum ascenditur tamquam per scalam Iacob de

terris ad celum, quorum tres continet affectus cordis, tres

amor anime, et tres dileccio uirtutis, puta fortitudinis,

quamadmodum scriptum est: Diliges Dominum Deum tuum ex toto

corde tuo, quod ad affectum pertinet, ex tota anima tua quod

pertinet ad amorem, ex tota virtute tua quod concernit

dileccionem.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 59, fol. 32

Birgitta, Revelationes V , Julian and the Ladder

Quoting St Bernard:

I believe that the chief reason why God who is invisible, willed to be seen in the flesh and to converse with men as man, was that in the case of carnal men, who could not love save in a carnal way, he might first attract all their affections to a salutary love of his humanity, and so gradually leave them on to spiritual love.

go hanc arbitror precipuam

inuisibili Deo fuisse causam quod uoluit in carne uideri et

cum hominibus homo conuersari, ut carnalium uidelicet qui

nisi carnaliter amare non poterant, cunctas primo ad sue

carnis salutarem amorem affecciones retraheret, atque ita

gradatim ad amorem perduceret spiritualem.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 60, fol. 32v

And again:

To sum up briefly; to love with one's whole heart is to disregard for love of the sacred humanity all that is attractive whether in one's own person or in that of others, including also the pride of this world.

uibus premissis talem iugit

conclusionem dicens: Ergo ut breuiter dicam, 'toto corde

diligere' est omne quod blanditur de carne propria uel

aliena, sacrosancte carnis amori postponere, in quo et

comprehendo gloriam mundi.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 62, fol. 33v

The soul of the just person is the throne of wisdom.

Anima iusti sedes est sapiencie.

Repeated, Norwich Castle Manuscript , fol. 78v, from Proverbs 10.25b; cited, Gregory, Hom. XXXVIII in Evang . PL 76, 1282:'. . . iusti sedes est sapiencie. ffor as seith holy write the soule of the ry3tful man or womman is the see & dwelling of endeles wisdom that is goddis sone swete ihe If we been besy & doon our deuer to fulfille the wil of god & his pleasaunce thanne loue we hym wit al our my3te'; in Walter Hilton in Westminster Manuscript; in Julian's conversation with Margery Kempe of Lynn. Integral to Julian's thought.

. . . the sons of Belial, who, puffed up with knowledge, are wont to despise simple, unlettered folk who are not so learned as they are. Let the meek hear it too, and rejoice that there is a knowledge of holy Scripture which is to be learnt from the Holy Ghost and is manifested in good works. Often enough a layman has it while a clerk has not, a fisherman has acquired it but not a doctor of theology. Its name is love or charity, for according to Gregory: 'Love itself is knowledge' - that is knowledge of the one towards whom the love is directed.

. . . filii Belial, inflati sciencia, qui simplices quosque et idiotas contempnere solent, quia non pollent litterature sicut et ipsi. Audiant quoque manueti et letentur, quod est quedam sciencia sacre Scripture que a Spiritu Sancto didiscitur et per bona opera manifestatur, quam sepe nouit laicus et nescit clericus, nouit piscator et ignorat retor, didicit uetula et non doctor in teologia, que dicitur amor siue caritas, quia secundum Gregorium amor ispe noticia est et eius in quem diriuatur.

Take the case of a very learned man who does not love God. What does he know about God? Let him answer that himself, and be ashamed in future to despise others. He may see their faces, but he does not see their hearts, in which a precious treasure may lie hidden, namely that very unction which would teach him all things, and without which the prudent is rejected by the Lord. This unction is rightly believed to be the Holy Ghost . . .

. . . quid si nichil amat aliquis magne literature Deum, quid nouit ille de Deo, respondeat ipse et erubescat ceteros de cetero despicere; quorum licet faciem uideat, non tamen uidet in corde, in quo abscondi poterit tesaurus desiderabilis, ipsa uidelicet unccio quo doceat eum de omnibus, sine qua perditur sapienciam sapiencia et prudencium intelectus a Domino reprobatur, que recte fore creditur Spiritus Santus . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 63, fols. 34-35. Especially intriguing in this comment, that John Whiterig earns his keep as a fisherman, has studied theology at Oxford, combining Benedictine work, study, prayer.

'For God loves a cheerful giver'. See what cheerfulness wins for the worker, the love of God himself.

ilarem enim dateram diliget Deus'. Ecce quid

mereatur hilaritas operantis, amorem uidelicet Diuinum.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 67, fol. 36

I am therefore of the opinion that cheerfulness adds just as much to an action as action adds to right intention, for cheerfulness in the doer is at once both a sign and an effect of a loving heart, and if we have not got that, all we do goes awry.

antum reor ergo hilaritatem

addete operi quantum addit opus bone uoluntati, quia

hilaritas factoris signum simul est et effectus cordis

diligentis, sine qua prauum est quicquid agimus.

antum reor ergo hilaritatem

addete operi quantum addit opus bone uoluntati, quia

hilaritas factoris signum simul est et effectus cordis

diligentis, sine qua prauum est quicquid agimus.

Julian on a cheerful giver

. . . and so the Church sings of our most blessed patron Cuthbert:

Rejoicing he did e'er fulfil

The

law of God throughout his days,

With

bounteous, radiant, gay goodwill;

His

merits won him lasting praise.

nde et de beatissimo patrono

nostro Cuthberto canit Ecclesia et dicit:

Legis

mandata Domini

letus

inpleuit opere,

largus,

libens, lucifluus,

laudabatur in meritis.

Lindisfarne Gospels, created on St Cuthbert's Lindisfarne and placed in his coffin when it was brought back to Durham for protection from Vikings, note stating it fell into the sea during the voyage, then was miraculously recovered, 'quod demersus est in mare'. Manuscript opening of Luke's Gospel, 'multi cona[n]ti sunt ordina[re n]arrationem', in which Luke writes to Theophilus, 'Friend of God ', telling him that many have sought to narrate the Life of Christ as their Gospel ministry, and he is assembling and organizing these accounts after verifying them. Old English interlinear gloss. By Permission of the British Library, Lindisfarne Gospels, St Luke's Gospel, MS Cotton Nero D.IV.fol 139.

See also Maria Makepeace, Codex Amiatinus, related to Lindisfarne, now in the Laurentian Library, Florence.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 68, fol. 36

The third degree is reached when a man is so fired with the love of God that he is neither elated by prosperity nor cast down by adversity, and if riches abound, he by no means sets his heart on them; if he happen to lose them, it causes him no regret at all.

ercio uero amoris gradus est

quando tantum incanduerit aliquem amor Dei ut neque eleuatur

prosperis neque deiciatur aduersis, et diuicie si affluent,

in nullo cor apponat, ac si eas perdere contigerit, nichil

pro illis doleat . . .

ercio uero amoris gradus est

quando tantum incanduerit aliquem amor Dei ut neque eleuatur

prosperis neque deiciatur aduersis, et diuicie si affluent,

in nullo cor apponat, ac si eas perdere contigerit, nichil

pro illis doleat . . .

. . . Attachment to temporal goods distracts the mind from love of divine things, and it is evident that the more intense delight a man takes in the things of this world, the less he loves God. . . . The Venerable Bede explains this as follows: 'No one can serve two masters, because no one can love at the same time both things transitory and things eternal. For if we love eternity, we make use of all temporal things without becoming attached to them.

ffeccio denique temporalium

dissoluit mentem ab amore diuinorum, et tanto Deus

comprobatur ab aliquo minus diligi, quanto diligens

reperitur terrenis delectari . . . quod exponens Venerabilis

Beda ita dicit: Nemo potest duobus dominis seruire, quia

nemo ualet simul transitoria et eterna diligere. Si enim

eternitatem diligimus, cuncta temporalia in usu non in

affectu possidemus.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 70, fol. 37

. . . those who, though their tonsure marks them as liars, seem to be able to say to the Lord: 'Behold we have left all things and have followed thee'. They have not really done so, for their hearts are still attached to the things which their habit proclaims them to have abandoned, and in their avarice they fly from him whom have ostensibley made profession of following in the way of love.

. . . qui per tonsuram quamuis mencientes, posse uidentur Domino dicere: Ecce nos reliquimus omnia et secuti sumus te, quod uere non faciunt dum hiis que habitu uidentur reliquisse animo coniunguntur, et quem per amorem uidentur professione sequi auaricia fugiunt.

St Augustine says of such men: 'Just as I know none better than those who have gone forward in the religious life, so I know none worse than those who have made a failure of it'. And St Gregory in one of his homilies says: 'I do not think that anyone in God's Church does more harm than the man who wears a religious habit, and, though behaving unworthily, enjoys a reputation for sanctity'.

. . . de qualibus ita dicit Augustinus: Sicut non noui meliores hiis qui in religione profecerunt, sic nec peiores hiis qui in religione defecerunt. Vnde beatus Gregorius in omeliis ita dicit: Nemo credo in Ecclesia Dei magis nocet quam qui sub habitu religionis indigne agendo nomen sanctitatis tenet.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 71, fols. 37v-38

Reason tells us that a man possessed of freedom does only what he chooses to do; but where there is love of God, there too is the Holy Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom; therefore whoever loves God possesses freedom. Whoever fulfils the law is no longer subject to it . . . Whoever loves fulfils the law, and so the just man is free to do what he will because he desires no evil.

acio enim docet quod nichil

facit homo libere potestatis nisi quod uult, sed ubi amor

Dei est, ibi et Spiritus Sanctus est, ac ubi Spiritus

Domini, ibi est libertas; qui ergo Deum diliget libere

potestatis est, quia qui legem inpleuit iam legi non

subiacet . . .et qui diligit legem inpleuit; ergo libere

potestatis est iustus facere quod uult, quia nichil mali

uult . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 76, fol. 39v

'Pray without ceasing, giving thanks in all things', . . . as it is written: Hide your alms in the lap of the poor man, and they will pray to God for you'.

ine intermissione orate, in omnibus gracias agite',

. . . hinc scriptum est: 'Abscondite elemosinam in sinu

pauperis, et ipsa pro uobis orat ad Dominum'.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 77

Julian on Prayer

It is, however, worth noting that no one who arrives at this degree lives for long, and so it was that this very saint never finished his commentary on the Canticle, for when he was just explaining the meaning of the opening words of Chapter 3: 'In my bed by night I sought him whom my soul loveth', he died . . .

otandum uero est quod non diu

uiuit qui ad hunc gradum uenit, unde et idem sanctus opus

super Cantica non compleuit, quia exponendo principium

tertii capituli quod est 'in lectulo meo per noctem quesiui

quem diligit anima mea, ibi moriebatur . . .

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 81, fol. 41v

Julian, End of Westminster Manuscript

[Tale of the holy solitary and the young noble maiden, who told him:]

'all the laughter and gaiety which make people think me frivolous arise from joy caused by the exceeding great love which I have for Jesus, my spouse, whom I love above all things. to whom my virginity is pledged, and to whom I have dedicated myself with complete devotion, for he is my spouse, and I am his bride.' The hermit was amazed at her words, and asked her in astonishment whether she really did love Christ as much as she said. 'Indeed I do,' the girl replied, and so saying fell to the ground and breathed her last in the hermit's arms.

mnis risus meus et leuitas, quibus me putant homines

dissolutam, ex nimii amoris oriuntur gaudio, quo sponsum meum

Ihesum super cuncta diligo, cui et seruo uirginitatem meam,

atque me tota deuocione committo, quia ille meus sponsus est

et ego sponsa sua'. Hiis denique stupescens sermonibus,

anachorita pre admiracione interrogauit eam si Christum tantum

diligeret sicut dixit. Cui cum uirgo respondisset 'Immo

diligo', statim cecidit in terram et inter brachia heremite

spiritum exalauit.

mnis risus meus et leuitas, quibus me putant homines

dissolutam, ex nimii amoris oriuntur gaudio, quo sponsum meum

Ihesum super cuncta diligo, cui et seruo uirginitatem meam,

atque me tota deuocione committo, quia ille meus sponsus est

et ego sponsa sua'. Hiis denique stupescens sermonibus,

anachorita pre admiracione interrogauit eam si Christum tantum

diligeret sicut dixit. Cui cum uirgo respondisset 'Immo

diligo', statim cecidit in terram et inter brachia heremite

spiritum exalauit.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 85, fol. 44

[This Parable in Whiterig functions like that of the Lord and the Servant in Julian]

. . . John Crysostom is right in saying: 'Whoever despises the whole world is greater than the whole world'.

i uero qui contempnit, ut

dicit Iohannes Crisostomus, totum mundum, melior est toto

mundo.

For the world was made for man, not man for the world, and as Hugh says in the Bethrothal Gift of the Soul : 'The wicked exist, not for their own sake, but in order that they may try God's elect'.

uia enim non homines propter

mundum sed mundus propter homines, nec reprobi propter se

uiuunt, ut dicit Hugo de Arra Anima, sed propter electos Dei

exercendos.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 96, fol. 49

Julian quotes Bethrothal Gift of the Soul

O if only I knew one of God's friends, who was ever filled with ardent love for him, how gladly would I submit to his teaching, and how eagerly hearken to his glowing words!

si unum amicorum Dei

nossem qui iugitur eius arderet amore, quam libenter dictis

eius obtemperarem et ignitum eius eloquium audirem

uehementer! quia reuera non potest igneum pectus nisi ignita

prodere uerba . . .

si unum amicorum Dei

nossem qui iugitur eius arderet amore, quam libenter dictis

eius obtemperarem et ignitum eius eloquium audirem

uehementer! quia reuera non potest igneum pectus nisi ignita

prodere uerba . . .

And now in conclusion I beg thee, sweet Jesus, who art both the beginning and the end, grant that I myself may have such an end, . . . and may so pass through the good things of this world that I may not at the last lose those of the next.

inc in fine deprecor te, Ihesu

bone, qui es in principium et finis, ut tali me fine facias

potiri quo unus de grege electorum merear inueniri, atque

sic transire hic per bona temporalia ut finaliter non me

contingat perdere eternalia.

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 97, fols. 49-49v

Julian, End of Westminster Manuscript

Pray

protect us, e'er direct us, and at death's decisive hour,

Stay

prevailing, lest we failing should succumb to Satan's power.

Fiends'

disguises, wiles, surprises, banish from us far away,

Lest

they tear us and ensnare us, making us their helpless prey.

Saving

power, Mary's flower, bear us up to Heaven high,

Where

the seeing of God's Being will our longing satisfy.

Amen.

n presenti nos conserua,

atque mortis termino

n presenti nos conserua,

atque mortis termino

Sis tu

prope, ne Minerue demur tirocinio;

Fuga

laruas et proteruas demonum astucias,

Ne nos

soluant ac inuoluant suas per decipulas.

Custos

pie, flos Marie, porta nos palacio

Trinitatis cuius satis esta beata uisio.

Amen

Here ends the Contemplation Addressed to Christ Crucified.

EXPLICIT MEDITACIO AD CRUCIFIXUM

John Whiterig, Meditacio ad Crucifixum, Chapter 98

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

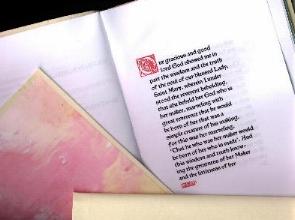

To see an example of a page inside

with parallel text in Middle English and Modern English,

variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a page inside

with parallel text in Middle English and Modern English,

variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton

Holloway. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e

Archivi 8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To

see inside this book, where God's words are in red,

Julian's in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

To

see inside this book, where God's words are in red,

Julian's in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville: Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp.

Index.

To view sample copies,

actual size, click here.

To view sample copies,

actual size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian

of Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20

Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook.

Preface, Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen

Press, 2010. x + 310 pp. ISBN-13:

978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10: 0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in

Julian of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates,

59 Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano.

Analecta Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und

Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN

978-3-903185-07-4. ix + 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of

Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to

its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||