THE JULIAN OF NORWICH

BRITISH LIBRARY

AMHERST MANUSCRIPT

(ADDITIONAL 37,790) PROJECT

Dearworthy Reader,

ILLIAM Langland

in Piers Plowman wrote movingly about

monasteries and schools of learning as not being places of

polemic. He was looking back rather to Benedictinism's contemplative,

book-producing-and-reading, monasteries, rather than towards

the seething universities of his day, where Benedictines,

Cistercians, Carmelites, Augustinians, Dominicans, and

Franciscans, could unite in condemning a woman, Marguerite Porete , to burning at the stake,

when not brawling against each other. Yet, in reaction

perhaps to that holocaust, Dominican men and women, the Friends

of God, came to

collaborate, across the face of Europe, in the writing of

contemplative texts, texts that will later be treasured,

Julian's among them, by exiled English Brigittine and Benedictine nuns on the Continent. While in England those texts follow in

the footsteps of Richard Rolle writing for Margaret Kirkeby

and were to be treasured in Carmelite and Carthusian

settings where men were encouraging women's contemplative

lives of prayer. These are rich textual communities,

shattered by the gender apartheid of the Universities, the

Renaissance and the Reformation.

ILLIAM Langland

in Piers Plowman wrote movingly about

monasteries and schools of learning as not being places of

polemic. He was looking back rather to Benedictinism's contemplative,

book-producing-and-reading, monasteries, rather than towards

the seething universities of his day, where Benedictines,

Cistercians, Carmelites, Augustinians, Dominicans, and

Franciscans, could unite in condemning a woman, Marguerite Porete , to burning at the stake,

when not brawling against each other. Yet, in reaction

perhaps to that holocaust, Dominican men and women, the Friends

of God, came to

collaborate, across the face of Europe, in the writing of

contemplative texts, texts that will later be treasured,

Julian's among them, by exiled English Brigittine and Benedictine nuns on the Continent. While in England those texts follow in

the footsteps of Richard Rolle writing for Margaret Kirkeby

and were to be treasured in Carmelite and Carthusian

settings where men were encouraging women's contemplative

lives of prayer. These are rich textual communities,

shattered by the gender apartheid of the Universities, the

Renaissance and the Reformation.

In the essay that follows, take the scholarly words as the least important of all, centring instead on the scraps and fragments of Julian's theology in Julian's words, that are present especially in manuscript form in this essay. So wrote a contemplative and anonymous monk as preface to our forthcoming edition of all the extant Julian manuscripts. And we warmly invite your participation in this Godfriends' project, as contemplative, as scholar, as general reader.

e

earliest surving Julian of Norwich manuscript may contain the

latest version of her Showing of Love. It is the Short

Text version, giving the date of its writing '1413', in its

97th folio, third and fourth lines as: 'Anno domini

millesimo.CCCC/xiij'. It was purchased at the Lord

Amherst Sale in 1910, becoming British Library Additional

37,790.

e

earliest surving Julian of Norwich manuscript may contain the

latest version of her Showing of Love. It is the Short

Text version, giving the date of its writing '1413', in its

97th folio, third and fourth lines as: 'Anno domini

millesimo.CCCC/xiij'. It was purchased at the Lord

Amherst Sale in 1910, becoming British Library Additional

37,790.

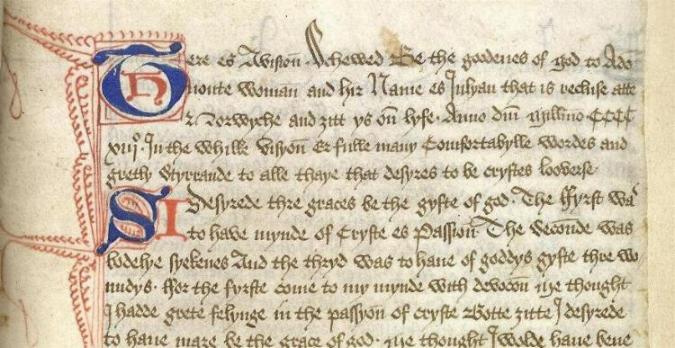

{

ere es Avisioun Schewed Be

the goodenes of god to Ade=/uoute womann. and hir

Name es Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt. ys

ou n lyfe. Anno domini millesimo

CCCC/xiijo. In the whilk visyoun Er fulle many

Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to alle thaye

that desyres to be crystes loovers.

ere es Avisioun Schewed Be

the goodenes of god to Ade=/uoute womann. and hir

Name es Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt. ys

ou n lyfe. Anno domini millesimo

CCCC/xiijo. In the whilk visyoun Er fulle many

Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to alle thaye

that desyres to be crystes loovers.

{  Desyrede thre graces be the

gyfte of god The ffyrst was/ to have mynde of Cryste es

Passioun. The Secounde was/ bodelye syekenes And the

thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=/undys. ffor the

fyrste come to my mynde with devocoun me thought/ I

hadde grete felynge in the passyou n of cryste Botte

3itte I desyrede/ to haue mare be the grace of god. me

thought I wolde haue bene

Desyrede thre graces be the

gyfte of god The ffyrst was/ to have mynde of Cryste es

Passioun. The Secounde was/ bodelye syekenes And the

thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=/undys. ffor the

fyrste come to my mynde with devocoun me thought/ I

hadde grete felynge in the passyou n of cryste Botte

3itte I desyrede/ to haue mare be the grace of god. me

thought I wolde haue bene

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

This first folio is tantalizingly marred by a repair, a strip of paper pasted to its edge taking the place of now lost annotations. They were likely made by the Carthusian James Grenehalgh, to be discussed later in this essay.

The whole manuscript is a florilegium assembled by one scribe whose dialect is of Grantham, Lincolnshire,

Miles Stapleton's Book of Hours inclusion of the Passion told from the four Gospels in Latin by an Augustinian Hermit seems influenced by Julian's vision:

aaa

[For more information on the Carmelites Richard Misyn and Adam Hemlyngton and the recluses Margaret Heslyngton and Emma Stapleton, see the Oxford M.Phil thesis by Johan Bergstrom-Allen online at http://www.carmelite.org/jnbba/thesis.htm§]

This same Amherst scribe, according to A.I. Doyle, also writes out Mechtild von Hackeborn, Book of Gostlye Grace, British Library, Egerton 2006 (owned by King Richard III and his wife, Anne Warwick) and a Middle English translation of Deguileville, St John's College, Cambridge, G.21.

THE SHOWING OF LOVE'S CORRECTOR

There are interesting corrections made to the Amherst Julian of Norwich Showingof Love text but not elsewhere in Amherst in a hand that reminds one of the Norwich Castle Manuscript . Given that the Showing of Love text itself stresses that it is being written in '1413' during Julian's lifetime, it is just within the realm of possibility that we have her here correcting her scribe, completing his lacunae, his eye-skips. This hand also seems to match that of the rubricator to this part of the manuscript.

Fol. 101v. +therfore it semed to me that synne is nou3t. ffor in all e thys synne

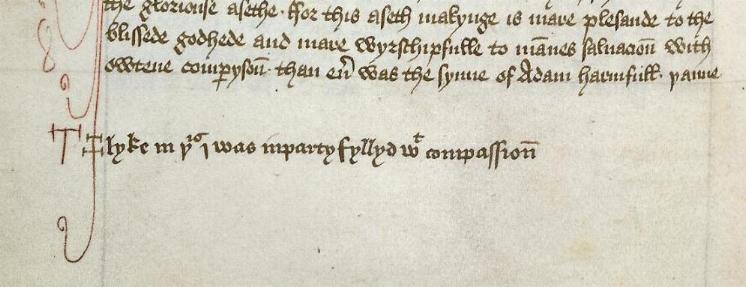

Fol. 106v . T+ lyke in this i was inparty fyllyd with compassioun

Fol. 107 . + & it langes to the ryalle lordeschyp of god for to haue his prive consayles

Fol. 108v . +what may make me mare to luff myne evencristen

As with the Westminster Cathedral and British Library Amherst Manuscripts the Norwich Castle Manuscript (Norwich Castle 158.926/4g.5), is a florilegium of contemplative and catechetical texts. It is said to contain 'Theological Treatises', specifically 'An Epistle of St Jerome to the Maid Demetriade who had vowed Chastity', a 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins', a 'Treatise on the Pater Noster', and 'Pore Caitif'. Richard Copsey, O.Carm. notes that the 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins' is written by Richard Lavenham, O.Carm., who lectured on Birgitta's Revelationes at Oxford and who was Richard II's confessor. The work is dated by paleographers as written in the beginning of the 15th century. Its dialect is of the Norwich region. This gives us a manuscript produced during Julian's lifetime, in the region where she was enclosed and, like Amherst, with both Carmelite and Brigittine associations. It begins with a letter written, it says by Saint Jerome (though actually by Pelagius) to the maid Demetriade who had vowed virginity. Its other texts are of interest for catechetical purposes, the Pore Caitif, the 'Treatise on the Lord's Prayer'. Much of its wording directly reflects that in Julian's Long Text Showing of Love .

It begins with a

lovely Gothic letter { in

gold leaf upon a purple ground:

in

gold leaf upon a purple ground:

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 1

It also has

another letter { given in a less florid decorative manner at folio

31:

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 31.

It seems worthwhile to compare these capitals with those in Amherst:

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol 97. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

The scribes of the two manuscripts are

clearly not the same but their layout is similar, as if the

writer of the Norwich Castle Manuscript had had the employment

of the scribe of the Amherst Manuscript, perhaps for the

production of a book for one Emma Stapleton who would later

become an enclosed anchoress with the Carmelites in Norwich.

Both manuscript texts begin, not with thorn, but with TH.

Another most beautiful manuscript Julian likely saw, owned by

Adam Easton, O.S.B., of Norwich, has a similarly beautiful

Gothic { for Trinitas, in gold leaf with green intertwines,

beginning its invocation to Wisdom, the Prayer of St

Dionysius, in its fine thirteenth-century Victorine

manuscript, now at Cambridge University Library. Amusingly,

Amherst's {

for Trinitas, in gold leaf with green intertwines,

beginning its invocation to Wisdom, the Prayer of St

Dionysius, in its fine thirteenth-century Victorine

manuscript, now at Cambridge University Library. Amusingly,

Amherst's { ,

with the smaller

,

with the smaller  nestling within, is unwittingly

replicated on the present gate to THE

BRITISH LIBRARY at St Pancras.

Perhaps nothing but coincidences, but nevertheless Italians

would call these, 'elegant combinations'.

nestling within, is unwittingly

replicated on the present gate to THE

BRITISH LIBRARY at St Pancras.

Perhaps nothing but coincidences, but nevertheless Italians

would call these, 'elegant combinations'.

If we compare the hand of the corrector to the Amherst Showing of Love to that of the scribe of the Norwich Castle Manuscript we see some similarities. They share a squarishness. (Likewise the hand of Cardinal Adam Easton of Norwich, who predeceased Julian, has a squarish, Tudor-seeming, quality to it. The Amherst corrector and the Norwich scribe share similar m's, n's, l's, k's, d's, a's, e's, &'s and yochs. However the Norwich Castle Manuscript is written in a deliberate bookhand with differently formed thorns, w's, s's and y's to those of Amherst's corrector, the h's and ff's having different descenders.

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 101v. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 31.

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 108. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Likely in neither the corrector to Amherst nor in the Norwich Castle Manuscript do we see Julian's actual hand. Nevetheless it is possible that Dame Emma Stapleton could have corrected Dame Julian's text, having another at hand from which to supply lacunae. Or that these corrections are made later at Syon Abbey where the largest secure collection of Julian's Showing of Love manuscripts came to hand, in the Sisters' library there (it is not listed in the surviving Catalogue for the Brothers' Library), until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

THE AMHERST FLORILEGIUM'S CONTENTS

The Amherst Manuscript florilegium is intended for a Latin-less woman contemplative, likely of the generation following Julian's. The manuscript may include translated texts originally in Julian's own contemplative library, then recycled by copying it out for a later anchoress. One can envision Julian herself leaving instructions as to what it should contain. This entire manuscript, and another by this scribe, are worthy of study in the collaborative spiritual direction of women anchoresses, and of their own production of theological texts, by Marguerite Porete, Julian of Norwich, Birgitta of Sweden, Mechtild of Hackeborn. With the inclusion of the works by Porete, Suso and Ruusbroec this collection is also related to the Dominican movement on the continent, known as the Friends of God , where Porete was influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius and William of St Thierry, her clandestine work influencing in turn Meister Eckhart and his disciples such as John Tauler and Henry Suso, a movement characterized by deep respect for women and indeed collaboration with them in the creation of contemplative theological texts. This movement, in turn, through Magister Mathias, who associated with the Dominicans in Paris and Stockholm, strongly influenced Birgitta of Sweden.

Among the texts now transcribed from the Amherst Manuscript on this Website are those of Froidmont , Ruusbroec , Suso , but not Porete :

Bernard of Clairvaux [Thomas de Froidmont] The Golden Epistle, Written for His Sister Margaret of Jerusalem (A95v-96v). [Other related texts are the Life of Christina of Markyate and the Flemish account of the Life of Jan van Beverley, John of Beverley, whom Julian mentions in her Long Text.]

Jan van Ruusbroec Sparkling Stone Complete (A115-130)

Brief excerpts from St Birgitta of Sweden

An amateurish drawing on the final folio of a mother and child where the mother is cross-nimbed, the cross made from three great nails, but not the child. The Short Text omits Julian's discussion of 'Jesus as Mother'. Yet this drawing appears to know of that theological argument and to portray it. This knowing is possible if the manuscript came to rest in a communal setting with access to the other versions of Julian's text. The manuscript drawing is especially intriguing in a Brigittine context where the Sisters wear white crowns with crosses, five red roundels at the interstices upon their black veils, in memory - and contemplative knowing - of the Five Wounds of Christ.

Courtesy, Juliana

Dresvina

Courtesy, Juliana

Dresvina

In relation to these see also John Whiterig, Contemplating the Crucifixion , Durham Manuscript B.IV.34.

THE '1413' SHORT TEXT'S CONTEXTS

I. EUROPE

Julian is writing her Short Text in a context that is both Continental and Insular, both European and English. If she is having it written in 1413, her likely former patron, certainly a 'Aman . . . of halye kyrke ', Cardinal Adam Easton of England, Benedictine of Norwich, is dead. His titular basilica in Rome was Santa Cecilia in Trastevere.

The Short Text manuscript of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love stresses St Cecilia by engrossing that name at fol. 97v, and the text makes use of St Cecilia's three neck wounds,

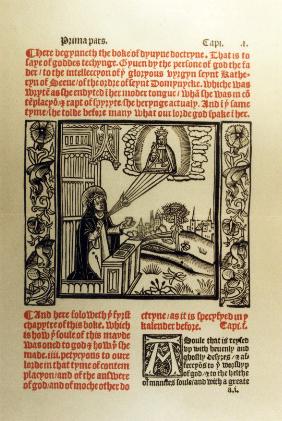

And here foloweth the fyrst/ chapytre of this boke. Which/ is how the soule of this mayde/ was oned to god & how then she/ made .iiii. petycyons to oure/ lorde in that tyme of contem/placyon and of the answere/ of god and of moche other do/ctryne: as it is specyfyed in the/ kalender before. Capt.1.

{A} soule that is reysed up/ with heuenly and/ ghostly desyers & af-/feccyons to the worshyp/ 00Oof god & to the helthe/ of mannes soules with a greate . . .

________

|| The Orcherd of Syon (London: Wynken de Worde, 1519); The Orcherd of Syon, ed. Phyllis Hodgson and Gabriel M. Liegey (London: Oxford University Press, 1966), EETS 258.18:11.||

Related to the three wounds of Cecilia are also the five wounds of Christ. Several English manuscripts speak of a solitary and recluse woman who sought to know Christ's wounds: Oxford, Bodleian Library, Lyell 30, XV Os of St Birgitta, ' A woman solitari and recluse covetyng to knowe cristis woundus '; British Library, Add. 37,787, fols. 71v-74, ' Femina quedam solitaria et reclusa vulnerum xristi scire cupiens ', waiting thirty years to do so, 'Sciendum est ante quod signis in peccatis esset triginta annis '; Harley 172, fol. 3, on Orysons on wounds shown to a solitary and recluse woman, 'She covetynne to knowe the nombre of the wondys of oure lord Jhesu cryst oftyne tymes she prayede God of his specyal grace that he wolde vouchsafe to shewe hym to hire '; Harley 494, fols. 61-62, echoes Amherst's ' Ade=uoute womann, and hir Name es Julyan that is recluse atte Norwyche ', and crystallizes all the above when speaking of ' Certaine prayers shewyd unto a devote person called mary Oestrewyk '. For Julian of Norwich lived near Westwick Street and Gate in Norwich and Adam Easton wrote his name 'OESTONE'.

New material in this version of the Showing of Love, added to its ending, and not in the Westminster or Paris texts, is from Alfonso of Jaén, Epistola Solitarii ad reges (1373), discussing the Discernment of Spirits and written in defense of Birgitta of Sweden's visionary Revelationes ,

The text is also to be found in Cambridge University Library, Ff.VI.33, fols. 38v-39, clustered with manuscripts which came there from Adam Easton's library at Norwich Cathedral Priory and from Syon Abbey.

II. ENGLAND

There was already anxiety, as well as support, on the Continent for women's visionary writing. It was to particularly be seen in the later condemnation by Jean Gerson, Chancellor of the University of Paris, of Marguerite Porete, Birgitta of Sweden and Jan van Ruusbroec. Though he was to amicably resolve his debate with Christine de Pizan, both agreeing to loathe the lecherous, sexist Roman de la Rose.

In England this anxiety and debate was further complicated by the political situation where John Wyclif's Lollardy was seen as instigating the Peasants' Revolt and the Oldcastle Uprising. Lollardy became punishable as both treason and heresy. Particularly singled out were lay persons, above all women, daring to teach theology, to write books and to translate the Bible into the vernacular. For the document promulgating and confirming censorship for the period 1401 through 1413 in England, see Archbishop Chancellor Arundel, Constitution, 1408.

It is generally held that the greater simplicity, childishness and recall of the Amherst Julian Short Text indicates that it was written earlier, immediately after the 1373 'death-bed' vision it describes. While the Long Text's self-proclaimed dating of 1387-1393 is accepted at face value. Scholars have paid little heed to the Amherst date, '1413'. But a study of the 1413 context shows tremendous anxiety, and indeed one medievalist, Rita Copeland, speaks of deliberately instilled 'infantilism' during this period. The drastic changes between the Long Text and the Short Text are that the Long Text gave vast swathes from the Bible in the most exquisite English, while the Short Text excises most of these - as was required by Arundel's 1408 Constitution and for which transgression had been punishable since 1401 with De heretico comburendo , as was indeed done to William Sawtre, Margery Kempe's curate at St Margaret's, Lynn. William Sawtre, through St Margaret's Church, Lynn, is also connected to Adam Easton's Benedictine Priory in Norwich (which also had oversight over Carrow Priory and St Julian's Church) which had its oversight. Julian would probably have known of both Marguerite Porete and of William Sawtre's grim fates.

Pageant XLVII. King Henry VI is crowned king of France in Paris, by his great-uncle, Cardinal Beaufort, 16 December 1430

Another illumination in Beauchamps' Pageants shows the Earl being made a Knight of the Garter after he has been successful in putting down the Lollard uprising, contemporary with the dating of the Amherst manuscript's version of the Showing of Love:

Courtesy of the British Library. Pageant XXIV. Henry V with the lords of his council and Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, in armour, after he had been instrumental in suppressing the Lollard rising, 1414.

JULIAN AND MARGERY: SHOWING AND BOOK

Around the date of '1413', Margery Kempe from Lynn visited Julian in her Norwich Anchorhold and later gave a remarkable account of their conversation together. The two texts, Julian's and Margery's tally, and they especially tally for the '1413' Short Text rather than for the more sophisticated Westminster and Paris/Sloane Long Text Versions whose manuscripts give dates of '1368' and '1387-1393'. Under Arundel there was great danger where a woman anchoress was perceived as subtle and sophisticated in her reasoning. Julian, circa 1413, in response to such exigencies, simplifies and crystallizes her teaching. But she does not fall silent. Comparing Julian's Showing of Love to The Book of Margery Kempe, we especially see Margery's account of her conversation with Julian to centre on the topic both the Short Text and this conversation share, the burning topic of the day, the 'Discerning of Spirits'.

Moreover, in The Book of Margery Kempe, it is not without interest that Margery's visit to Julian is immediately preceded by that to the saintly Carmelite. William Southfield of Norwich: 'a Whyte Frer in the same cyte of Norwyce whech hyte Wyllyam Sowthfeld', who died, 26 August 1414. Margery's spiritual direction comes from Carmelites, such as 'Maystyr Aleyn'. D.D., of Lynn, who compiled indices of St Birgitta's Revelationes, and Dominicans mainly, in the latter case, with close connections to Catherine of Siena through Raymond of Capua.

The comparison of these texts, transcribed directly from their manuscripts is given in The Soul a City: Julian and Margery .

The Amherst Manuscript was later annotated untidily by the Carthusian James Grenehalgh for the Brigittine Joanna Sewell of Syon Abbey.

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 108v. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Here we see where the tortured and sinning James Grenehalgh, who marred many contemplative books in this way (he was eventually literally sent to Coventry by his brethren), responds to Julian's text, written out collaboratively between two scribes, one correcting the other and of whom the second may have been Julian herself at 70. Here, Grenehalgh writes untidily in the margin, as well as underlining these words the text, 'contrition', 'confessyon', 'penaunce', and for 'domesmann', 'gostly father'. Julian's discussion of the sacrament of penance looks back to the beginning of her text concerning her desire to know Christ's wounds, and those of St Cecilia, defouling ' the fayre ymage of god' which the original rubricator to the text underlines in red . We recall Julian's anguish about not confessing her vision when one ' growndyd in haly kyrke' suddenly became interested in it, back in May, 1373, now fifty years earlier than this manuscript version's stated date of 1413.

Francis Blomefield, closer to Julian's

time, spoke of Carrow Priory as having been a school for young

women. Then Julian had likely earned her keep, Dom Jean Leclercq

reminds us, as a grammar teacher of small boys and as a

catechism teacher, until Archbishop Arundel's stern prohibition

was promulgated against women teaching theology. At which point

her name appears in Wills, for she has lost her livelihood and

means of support, given the draconian measures against Lollards.

We see in the eyeskip corrections to the text a hand that is

like a woman's, squarish, a bit amateur, but proficient in Latin

abbreviations, nevertheless. We also see in these excerpts from

this manuscript that Julian and her text function somewhat like

a confession manual, the Middle Ages' psychiatry, probing and

healing the wounds of the soul, giving 'comfortable words to

Christ's lovers', both women and men, as the male scribe

observes above in the introductory preface to her text. In doing

so he authorizes her. Indeed, we see in this collection of texts

associated with her echoes of such Church Fathers as Dionysius,

Augustine and Jerome/Pelagius, and more contemporary theologians

such as William Flete and Richard Lavenham. Women were not

permitted to teach theology (though in the Early Church women

were catechists to women) or to administer the sacraments (and

especially not confession), with the exception of baptism, or to

translate the Bible into the vernacular (though Paula and

Eustochium collaborated with Jerome with the Vulgate from Hebrew

and Greek into Latin). Women were, however, honoured for their

visions, revelations, showings, from God. Jerome praised those

of Paula at Calvary and in Bethlehem. Cardinal Jacques de Vitry supported

those of Mary of Oignies, this fact being noted by Birgitta of

Sweden's and Margery Kempe's spiritual directors concerning

their written revelations. Mary and John were equally shown

beneath the now mandatory medieval Roods, representing our

stance as women and men who are ' Christ's lovers'. Julian casts

her work in the form of the Revelation, the Showing of Love,

that she receives in illness from seeing the bleeding Crucifix,

but this is frame to her excellent teaching of the catechism

concerning the sacraments, especially, in this text, that of

penance. The Anchoress in her Norwich Anchorhold is a doctor of

the soul to such as Margery Kempe .

Even this manuscript's use of a male and clerical scribe may be

in response to her need for authorization, given Arundel's 1408

Constitution. Similarly Margery resorts to male and

clerical scribes to authorize her text. (Though I suspect her

initial scribe, whom she gives as her son, was her

daughter-in-law from Gdansk, where Birgitta's Revelationes

were especially cherished, both Margery and her daughter-in-law

needing to conceal the gender of the Book's writer.) We

see Julian's male scribe, who may be Carmelite, acknowledge

Julian's efficacy. We see a male reader, a Carthusian, do the

same. Her text attests, like a legal document for a canonization

process, to her saintliness. It also functions like a priestly

confession manual. Indeed, we still turn to it today for our own

soul healing.

THE MANUSCRIPT'S SUBSEQUENT HISTORY

Most Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love manuscripts which survive demonstrate connections with contemplative and Brigittine Syon Abbey, where they were clearly read, annotated and treasured by its Sisters. James Grenehalgh's annotations for Joanna Sewell connect it with Carthusian Shene Charterhouse and Brigittine Syon Abbey. Syon's downfall was to come about through the Benedictine nun from Canterbury, Elizabeth Barton, being encouraged by Dr Edward Bocking, O.S.B., likewise of Canterbury, to come to Syon Abbey and to write there a massive book, her Revelations, modeled on St Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes , St Catherine of Siena's Dialogo , and other women's books made available to her there in English. In her text she dared to prophesy against Henry VIII's impending marriage to Anne Boleyn. Every copy of her printed book was destroyed by Act of Attainder (25 Henry VIIII c.12), and she and her editor were executed. Following those executions would be that of St Thomas More who also frequented the library of Syon Abbey. The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript florilegium including Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love came into the recusant Lowe family, which continued their strong association with Syon Abbey, despite the drawing, hanging and quartering or imprisonment of several of its members, finding its way to Syon Abbey in Lisbon, then back to England. The Paris Manuscript of the Showing of Love was written out by the Brigittine Sisters in exile in Flanders, then left behind by them in Rouen when they had to flee precipitously to Lisbon. The Norwich Castle Manuscript has remained in Norfolk since its origins. The Amherst Manuscript, the only one by a male scribe, was also the only Showing of Love Manuscript that survives that has remained continuously in England.

Francis Blomefield noted that in his day the manuscript was owned by Francis Peck, a Leicestershire antiquary. It was Francis Blomefield who first discovered the Paston Letters. He responded to Julian's text with the greatest admiration, copying out its incipit, carefully, though erring as to its date, and speaking of her great reputation for holiness:

THE MANUSCRIPT'S EDITIONS

Sister

Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever

had. During the war years she was transcribing the extant

microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds

University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based

on her meticulous work.

Sister

Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever

had. During the war years she was transcribing the extant

microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds

University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based

on her meticulous work.

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

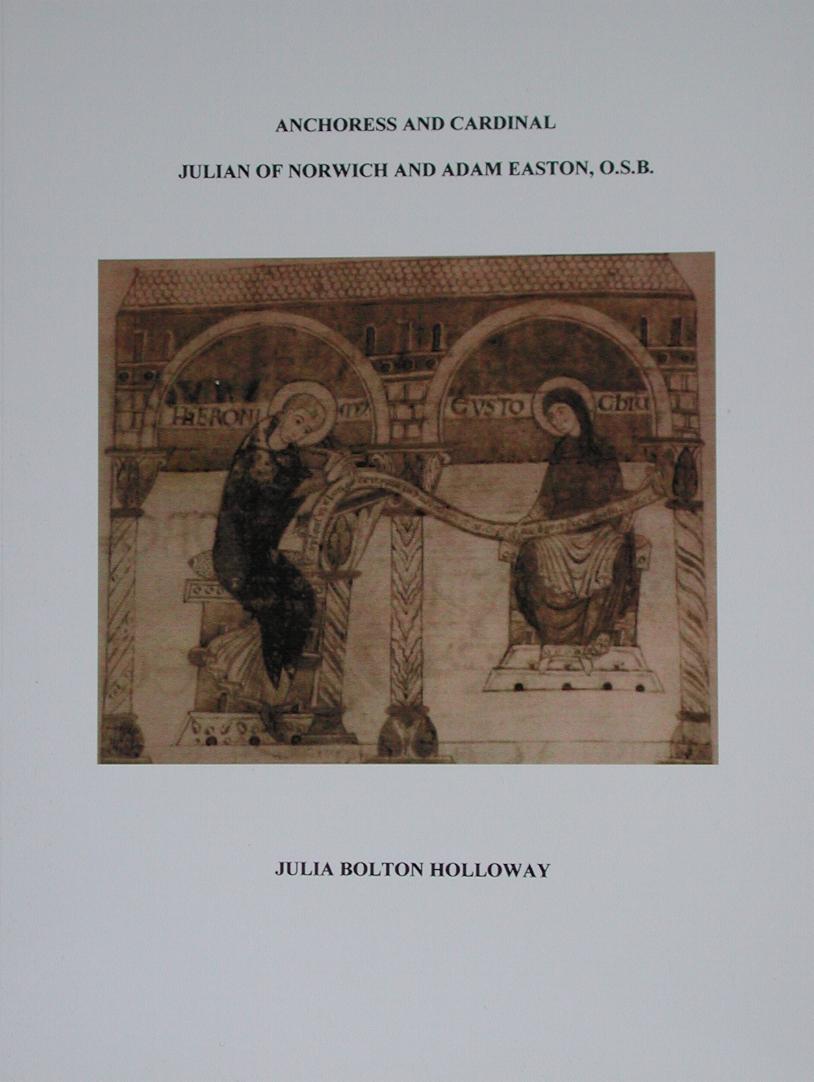

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Three: Divine Love in

Julian of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

UMILTA

WEBSITE, JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS

|| HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF

SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS,

BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||