BOOK REVIEWS: JULIAN OF NORWICH

Christopher Abbott || David

Aers and Lynn Staley || Wendy Love

Anderson || Denise Nowakowski Baker

|| Frances Beer || Ritamary

Bradley || Martin Buber || Robert H. Calderwood || Cloud of Unknowing, ed. Gallacher || Marion Glasscoe || Walter

Hilton, ed. Bestul || Julia Bolton

Holloway, ed. St Bride || Julia Bolton

Holloway, ed. Julian || Rosemary Horrox,

ed. || Jarena Lee in Spiritual Narratives || Deeana Copeland Klepper, ed. || M. Diane F. Krantz || C.S.

Lewis || Asphodel P. Long || Sandra J. McEntire, ed. || Ralph Milton || Bridget

Morris || Edward Peter Nolan || William F. Pollard, ed. || Ambrose Tinsley, O.S.B. || Lynn Staley || Karen

Sullivan || Sheila Upjohn || Vadstena Customary || Rosalynn

Voaden || Rosalynn Voaden,

ed || Nicholas Watson

Christopher Abbot. Julian of Norwich: Autobiography and Theology. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1999. Studies in Medieval Mysticism 2. xiv + 197 pp. Bibliography, index. ISSN 1465-5683

When Catholic Sister Ritamary Bradley titled her book, Julian's Way: A Practical Commentary on Julian of Norwich, she called attention to the need to not only study, but live, Julian's contemplative life, not only to analyse, but to practice it. On the other hand, Anglican Sister Benedicta Ward proclaimed that Julian was never a nun. Christopher Abbott has bravely sailed into the eye of this storm and written an academic book that overflows narrow boundaries, bringing to it his sharing of Julian's contemplative life, himself knowing both worlds, of the university and of the monastery. He reads Julian in lectio divina and his reading is wide and deep.

Much Julian scholarship is secondary, scholars quoting scholars, and thus building upon faulty premises. The major fault of most of these studies is the commonly believed ordering of the texts, the Short Text first, the Long Text later, and the Westminster Text ignored. A thorough study of all the Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love, manuscripts and their true ordering, garnered from primary research, is about to be published. Christopher Abbot has mercifully not set about proving the progress from one text to the other, but instead has sought to understand Julian.

On page 8, Christopher Abbot queries 'xxx' as being 'yowth'. But in the Lynn, Norfolk, Promptorium Parvulorum (Early English Text Society, Extra Series 102, 'Agis sevyn', column 7), we are given the Roman sense of youth as up to fifty, certainly beyond thirty, years of age. In his careful reading of her text he becomes aware that she is speaking of an earlier time and desire, prior to her vision and her writing of the Showing. He parallels her autobiographical strategy to John in his Gospel. He notes parallels also to Catherine of Siena and Birgitta of Sweden 's writings. And he speaks of Benedict's Rule, Guigo II's Scala, Augustine's Confessions, Bernard's On the Song of Songs, Aelred's De Institutione Inclusarum, Catherine of Siena's , on contemplative lectio divina .

Especially fine is his perception, albeit pretentiously worded, p. 45, 'The mystical coinherence through Christ of the personal and the ecclesiological implies a dissolution of the gap between Julian as differentiated subject of religious experience and the total community of her fellow Christians'. His chapters on Incarnation I. the Lord and the Servant, use Anselm and Augustine, and are especially illuminating on the slade as also the Virgin's womb, as Julian states, and II. The City of God, enclosing Adam/Christ. 'Human nature was/is created in a primary sense for Christ himself so as to be shared with all human beings, the adopted children of the Father and Christ's own brothers and sisters', p. 114, then citing Julian, 'Thus our lady is our moder in whome we are all beclosid and of hir borne in Christ; for that she is moder of our savior is moder of all that shall be savid in our savior', p. 160. He continues by saying, 'much more imporant to Julian than the details of Mary's appearance are "the wisedam and the trueth of hir soule', for she is 'fulfillid of grace', translating Gabriel's words 'Ave Maria, gratia plena', p. 161. He ends with the womb image, the birthing, the beginning, citing the work of my former colleague, Edward P. Nolan .

This book is highly recommended for all

Julian scholars and lovers.

David Aers and Lynn Staley. The Powers of the Holy: Religion, Politics and Gender in Late Medieval English Culture. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-271-01542-X. 310 pp. Bibliography, index.

A English Marxist and an American Feminist come together to do Theory upon Wyclif, Piers Plowman, Julian of Norwich and Chaucer. The Powers of the Holy: Religion, Politics and Gender in Late Medieval English Culture is thus an important, and deeply scholarly, book. But excised from it is the Power of the Holy, the reason for being of medieval literature, architecture and art, which then so clearly transcended merely mortal authority that it has now become suppressed everywhere. Today's fashionable academic discourse upon Julian is clearly uncomfortable with theology, and struggles, paradoxically, to win authorized approval through having co-opted Marxism, while obliterating its Gospel, and Feminism, while obliterating its Liberation. Nevertheless, in the final pages of this book all these obtain a shadow victory.

What is especially interesting in many of the scholarly books that follow in these review pages, by Baker, Beer, Glasscoe, is their thesis that the Short Text is earlier than the Long Text. Nicholas Watson in two brilliant Speculum articles has argued for the Short Text as later, but still earlier than the Long Text. In Aers and Staley there is uneasiness about the accepted paradigm, but not yet a willingness to shift, this anxiety being particularly noted in the footnote to p. 79, where they take issue with Watson's pushing of the dating of the Long Text into the reign of Henry V. Far better would be for all concerned to returned to what Julian's texts and manuscripts themselves say, that the Long Text was originally finished 20 years after the 1373 Revelation, in 1393; and that the Short Text was originally finished when Julian was still alive, 'yet on live', the manuscript's text giving that year as 1413. That date accords with everything that Watson has demonstrated concerning the anxiety of that period. While the Long Text accords with everything that Watson says about the halcyon confidence of the earlier period about 1393. Had this brilliant pair worked with the other, and historically likely, ordering they could have carefully demonstrated the suppression that takes place, in lieu of 'development', within Julian. And they could have celebrated Julian's courageous St Cecilia-like compliance/countering even of that suppression. The paradox is that it is in countering that censorship against women doing theology that Julian autobiographically enters the foreground of her text as visionary, as censored, as gendered. She is seventy. She will not be silenced. She speaks like Anna in the Temple, like Magdalen in the Garden.

David Aers, p. 95, rightly senses Julian's use of Piers Plowman's allegorical mode of thought in her Chapter 51 on the Lord and the Servant. Both texts are seeped in Wyclif's milieu. (Lynn Staley will note the relation to orthodox Thomas Brinton's Sermons 99, 100, pp. 151-152.) He also brilliantly notes how Julian counters other women's feminist use of milk and blood in relation to Christ. Lynn Staley begins her Julian chapter discussing the chronology of the writing of the various layers of the Showings, again with the premise that the Short Text is early. As before, Watson is discussed, pp. 110-112. By p. 126, Staley states correctly that the Long Text is clearly of the fourteenth, rather than the fifteenth, century, in so doing disagreeing with Watson, because its serenity would not be appropriate to the tensions of the Lancastrian period. On pp. 118-120 she falls into the slade of misreading 'soul' as 'soil', excrement. There is only one reading in the Middle English Dictionary of 'soul' in any way connected with filth, where 'foul' was written of a festering wound, but where the 'f' failed to get crossed, leaving it a long-tailed 's'. This accident has given rise to a generation of textual misreading that fall foul of the substance of what Julian wrote. Staley is particularly good on the context of the 'Lord and Servant' Parable. Indeed, throughout, the pairing of their work is always complementary one to the other.

Aers and Staley are correct in their dating

of the Long Text's composition, Watson, in his of the Short

Text. However, the proof of this ordering is given in the

publication of the 2001 edition and translation of Julian of

Norwich's Showings.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Anderson, Wendy Love.

<i>The Discernment of Spirits. Assessing Visions and

Visionaries in the Late Middle Ages</i>. Series:

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation/Studies in the Late

Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation 63. Tübingen, Germany:

Mohr Siebeck, 2011. Pp. x, 266. EUR 89.00. ISBN-13:

9783161516641.

Reviewed by Debra L. Stoudt Virginia Polytechnic Institute and

State University dstoudt@vt.edu

The discernment of spirits is central not only to the experience

of the visionary but also to that of the prophet, the reformer,

the magician--and occasionally the heretic. Identified by St.

Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians (12:10) as a gift of

the Holy Spirit, the ability to discern spirits serves as a

token of divine favor, one bestowed on a variety of individuals

throughout history. These men and women, clerics and laypersons

are remarkable not only for the gift they have received but for

its unique manifestation in their lives. In her engaging study

Wendy Love Anderson traces how prophecies and visions are

"received and understood by the visionaries themselves and by

the people around them between the twelfth and the fifteenth

centuries in Christian Europe" (2). The examination is an

outgrowth of Anderson's 2002 University of Chicago dissertation,

the title of which, "Free Spirits, Presumptuous Women, and False

Prophets: The Discernment of Spirits in the Late Middle Ages,"

draws attention to the marginal role in society played by many

recipients of the gift. The revised title and the study itself

give precedence to the historical context of the experiences and

the tradition of commentary that evolved concerning the

<i>discretio spirituum</i>.

The introduction begins with the response of delight by

Christina of Markyate around 1115 to a vision of the Virgin Mary

alongside the skeptical reaction of Veronica Binasco in the

second half of the fifteenth century to a similar experience.

What transpired in the intervening centuries? What

criteria merged by which true revelations could be distinguished

from false ones? What authority did religious and secular

powers wield concerning such matters? In the subsequent

chapters Anderson undertakes a contextualization of the

responses to these queries, linking the responses of succeeding

generations to explain the remarkable shift over time.

Anderson proposes the rediscovery of prophecy by European

Christians in the twelfth century as the impetus for change. The

visionary experiences of Franciscan clerics stimulate debate on

the topic in the thirteenth century, and by the fifteenth

century it is the visionary experiences of lay women take center

stage. The shift attests to the gendering of theological

discernment discourse and results in a multifaceted discourse on

the <i>discretio spirituum</i> in terms of gender,

ecclesiastical status, and the struggle for symbolic power by

the early fifteenth century (11). Anderson argues that the

question of authority maintains preeminence over that of gender

with regard to the gift of discernment (7), but it might be

contended as well that the two are inextricably intertwined.

In a section on the visionary context of discernment (4-8)

Anderson references recent literature, including Nancy Caciola's

<i>Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in

the Middle Ages</i> (2003)

and Dyan Elliott's <i>Proving Woman: Female Spirituality

and Inquisitional Culture in the Later Middle Ages</i>

(2004). She identifies the scholarly niche her study fills,

namely that "[t]he late medieval discourse on the discernment of

spirits was a visionary project (in both senses), a series of

reactions to key events in the history of Christianity, and a

dynamic conversation across several centuries addressing widely

diverse claims to religious authority within late medieval

Christendom" (8).

The first chapter outlines the biblical and patristic origins of

the Christian characterization of the discernment of spirits,

with its occasional exhortations to beware of false prophets and

claims that the clergy possess the gift <i>ex

officio</i>. Augustine's tripartite understanding of

visions--corporeal, spiritual, and intellectual--remains an

essential concept through the Middle Ages, but the advent of the

monastic tradition introduces a difference nuance to

<i>discretio spirituum</i>, one that reflects

"communal moderation" (36). The chapter concludes with the

advice of Bernard of Clairvaux on the subject and a brief

examination of the reception of the visionary

experiences of Hildegard of Bingen, Joachim of Fiore and

Elisabeth of Schönau at the end of the eleventh and the

beginning of the twelfth century, focusing on the question of

whether each is expected to prove her or his prophetic status

and how each understands that status.

Chapter 2 explores the impact of the new order and

the new mysticisms on discernment in the thirteenth century.

What proof is needed to confirm an individual's status as

prophet and who evaluates that proof become central themes of

papal letters and canon law. The diverse opinions within the

Franciscan Order are exemplified by the skeptical stance of

David of Augsburg toward the trustworthiness of revelations and

visions as well as the more defensive posture of Peter of John

Olivi. In the course of the fourteenth century Olivi's writings

are interpreted by other authors, e.g., Arnald of Villanova and

Augustinus of Ancona. Anderson situates the writings of this

time in the context of the historical ages set forth by Joachim

of Fiore at the close of the twelfth century and the growing

instability of the Church that culminated in the Avignon papacy

of the fourteenth century.

The focus of Chapter 3 lies squarely on the writings of a number

of Germanic theological figures. Henry of Friemar "the Elder"

sets forth criteria for the discernment of the spirits in the

tradition of the medieval scholastics. However, his critique of

the "philosophers" in favor of the holy men inspired by grace

serves as a precursor to the mystically informed writings of a

number of Dominicans, especially Henry Suso and John Tauler.

Suso uses the Middle High German

<i>underscheit/d</i> to translate Latin

<i>discretio</i> as well as

<i>distinctio</i> and touts the potential role of

visionary experiences in the spiritual guidance he offers. In a

similar vein, Tauler provides homiletic advice as to how to

distinguish the divine from the diabolic. The Dutch mystical

tradition is exemplified by Jan Ruusbroec, who examines

discernment as part of the inward life, providing direction for

those who might be tempted to spiritual error. Anderson

underscores the didactic nature of the writings of these figures

and examines the impact of the pronouncements in light of the

Free Spirit heresy, which she links to the "misapplication of

reason" in understanding spiritual teachings (122).

Chapter 4 is concerned with three individuals caught up in the

historico-religious events of the time: Birgitta of

Sweden, Pedro of Aragon, and Catherine of Siena. All are

advocates of the return of the papacy to Rome, and their

influence is examined in view of their authority as shaped by

"the proper place of revelation within the institutional Church"

(126). In all three cases the experiential relationship with

Christ serves a pivotal function. Anderson ascertains a shift to

a post-Schism idea of discernment, in which an outside authority

is called upon to validate the visionary experience.

Chapter 5 explores the role of medieval universities during the

years of the Great Western Schism in the debate regarding

discernment. Most prominent reformers are university-based

theologians eager to participate in church affairs. Drawing on

the commentary of previous, they conclude that the right to

determine the authenticity of visions and revelations is indeed

their prerogative (189). In this regard Anderson examines the

influential comments of Pierre d'Ailly on the question of true

and false prophecy as well as the doctrine of discernment of

Henry of Langenstein, who identifies false prophets as those who

lack <i>ratio</i> as well as

<i>discretio</i> (175). It is left to the pupil of

both men, Jean Gerson, to champion their ideas. The chapter

concludes with an excursus on critiques by various scholars of

the last century concerning the writings of the above- mentioned

theologians and reformers, with a focus on medieval women's

spirituality and the gendering of discourse. There have been

similar debates regarding the central figures in other chapters,

and one may wonder why only in this particular case the topic is

explored in depth.

Anderson's argument for a nuanced understanding of Gerson's

ideas and their evolution over time provides the context for the

first part of Chapter 6. The mature Gerson is convinced that

theologians must not

only be educated, they must also have an "ineffable encounter

with the divine" in order to provide guidance regarding

<i>discretio spirituum</i> (224). He becomes

increasingly moralistic as he compares theologians and

visionaries and ever more systematic as he establishes authorial

hierarchies for discerning spirits. Anderson interprets Gerson's

disparaging comments toward visionary women as more of a

critique of male confessors and the institutional church than of

the females themselves (213). However, at this time the topic of

female visionaries is a contentious one--as it has been

throughout history-- exemplified by the case of Joan of Arc,

whom Gerson defends in <i>Super facto puellae</i>,

although his arguments are misrepresented at her trial two years

after his death. The concluding pages review the salient points

of the study. Anderson also offers a glimpse into the "Future of

Discernment," with references to Savonarola as well as

Reformation and post-Reformation debates on the subject.

Anderson's presentation of the topic is even-handed, but any

study is selective by necessity. Women's spirituality is

explored at various points but seldom takes center stage.

Although devils are given their due, the topic of witchcraft is

avoided. Notably absent from discussion are representatives of

the English mystical and theological tradition, aside from the

introductory reference to Christina of Markyate. Likewise the

voices of female spiritual charges of the German Dominicans of

the Rhineland might have been heard or evidence from their

writings presented to support (or refute) the efficacy of the

spiritual advisors' guidance. Given the introductory chapter

summaries (13-16), there may have been the expectation of more

extensive commentary regarding certain topics, e.g., the choice

of vernacular languages among German and Dutch writers in the

thirteenth

century. However, these <i>desiderata</i> do not

detract from the argument the author sets out to make. Anderson

achieves her stated goal: she succeeds in neatly fitting

together selected pieces of the history of discernment of

spirits to provide a valuable, readable description of the

contours of its evolution in the late Middle Ages.

_________________________

<i>Responsiones Vadstenenses: Perspectives

on the Birgittine Rule in Two Tracts from Vadstena and Syon

Abbey. A Critical Edition with Translation and

Introduction</i>. Ed. Elin Andersson. Stockholm: Acta

Universitatis Stockholmiensis/ Studia Latina Stockholmiensis LV,

2011. Glossary, Index, Bibliography, Abbreviations, 3 b/w

Manuscript Plates. vi + 260 pp. SEK 375. ISBN 078-91-86071-59-2

I had earlier reviewed <i>Liber usuum fratrum monasteri

Vadstenensis/ The Customary of the Vadstena Brothers: A Critical

Edition with an Introduction</i>, edited by Sara Risberg

(Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 2003). Both

these books are of great usefulness for a study of London's Syon

Abbey, for the pair, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe of

Lynn, and for the cross currents of contemplative manuscript

compilations between Syon and Vadstena, between England and

Sweden..

<i>Responsiones Vadstenenses</i> at first hand

documents the resolution of tensions between the Brigittine

monasteries of Vadstena in Sweden, founded by Saints Birgitta

and Catherine, her daughter, and Syon Abbey in England, desired

by Henry IV and founded by HenryV in 1415. The 60 Sisters of

each house were intensely cloistered, the 25 Brothers not so

much and able to travel from one monastery to another and to

Rome. The Abbess, Christ tells Birgitta

[<i>Revelaciones</i> X Latin text: Sancta Birgitta,

<i>Opera Minora</i> I: <i>Regvla

Saluatoris<i/>, ed. Sten Eklund (Stockholm: Almqvist &

Wiksells, 1975); electronic version:

http://www.umilta.net/bk10.html], represents Mary, the Confessor

General, Christ. Two Syon brothers, one of them the future

Confessor General, Robert Bell, the other, Thomas Steryngton,

present their written questions to the Vadstena brothers who

respond to them, likewise in writing, keeping copies for their

own later use with the <i>Liber usuum</i>, etc. Two

years later than these documents, Syon was to absent itself from

the 1429 Brgitine General Chapter at Vadstena amicably but in

deference to the consecrated women's inability to travel and to

participate in the deliberations.

The Annales school and the work of André Vauchez on

canonizations have taught us upstairs/ downstairs history. James

Hogg at the University of Salzburg tirelessly and usefully

published texts and studies on monasticism, particularly

Carthusian, but also Brigittine. Roland Barthes' 1980

<i>Sade, Fourier, Loyola</i>, focussed on human

group constructs. <i>Responsiones Vadstenenses</i>

is a splendid book, combining textual editing with a window onto

international formation taking place through the universality of

the Latin language for western Europe. As with

<i>Revelaciones</i> V, the book in which Birgitta

resolves Magister Mathias’ theological doubts with questions and

answers in her vision while on horseback to the Castle of

Vadstena King Magnus granted her for her abbey, this book is in

the form of Latin questions and answers, in this case on how

best to interpret the Rule Christ gave Birgitta in visions while

she and her husband were at the Cistercian monastery of

Alvastra, despite the complications that Popes only allowed it

as a customary alongside the Augustinian Rule, and at times

officially ruled against the Brigittine espousal of the double

monastery form. During this international and friendly dialogue

between persons who have not met each other, references are made

to the libraries which both possess, copies of the Rule and the

<i>Revelaciones</i>, comments made on these by Prior

Petrus Olavi (<i>Addiciones</i>, often derived from

the <i>Extravagantes</i>) and by Bishop Hermit

Alphonso of Jaén (<i>Declarationes Dominorum</i>),

and even giving descriptions of his magnificently illuminated,

now lost, <i>Liber Alfonsi</i> codex, that Vadstena

had possessed before the Reformation, as well as to the papal

documents, <i>Mare Magnum</i> (1413) and

<i>Mare Anglicanum</i> (1425), concerning the

Brigittine abbeys and their indulgences. There were later to be

the Syon Additions, of which the nuns of Syon Abbey showed me

Tudor fragments they discovered in their attic at Totnes, these

likewise seeking to return to the charisma of their Mother

Foundress Birgitta and her Regula Salvatoris.

Though this is a conversation, an international written Latin

dialogue between men, it is carried out on behalf of the women

they serve, the Abbess and the nuns of the respective

communities of Vadstena in Sweden and Syon in England and

consequently it is women-centered, even feminist. It emphasizes

the architecture, the women’s choir above, the men’s beneath,

how communion is given to the nuns, to whom they confess, how

they profess, how they are buried, all this in relation to the

carefully planned Brigittine architecture. A later parallel to

such concerns can be seen in American Shaker architecture where

women are separate from men but equal if not higher in rank.

Conversations are to be held to a minimum, whether within

community or with outsiders, and to be opened with 'Benedicite'

with the response, 'Dominus', as with Benedictines (important in

Julian of Norwich), or with 'Ave Maria'. Both men's and women's

communities were bookish, the extensive catalogue of the men's

library surviving, though not that of the nuns'; however there

was to be no discrimination against an illiterate nun. Vincent

Gillespie and Christopher De Hamel have studied the men's

library survivals. I have instead been interested in those of

the women, finding that the <i>Revelaciones</i>, the

<i>Liber Celestis</i>, the <i>Orcherd of

Syon</i> and the <i>Myroure of oure Ladye</i>

(Early English Text Society O.S. 291, 178, 258, E.S. 19), as

well as early Julian of Norwich manuscripts, were treasured and

in some cases edited and prepared for publication by the

Sisters. While Uppsala University now has Vadstena manuscripts

confiscated at the Reformation where Katillus Thorberni and

others copied out texts from England: Richard Rolle, Mechtild of

Hackeborn, Walter Hilton, Adam Easton, etc (C1, C17, C159, C519

C621, C631).

The <i>Responsiones Vadstenensis</i>, written dually

by the Syon and Vadstena monks is accompanied in the volume by a

'Collacio' on the text, 'Vide, Domine et considera',

written by the Abbot of St Albans, John Whethamstead ('Excerpta

paucula de prima part Granarii Johannis de Loco Frumenti'), for

Syon's first acting Confessor General, Thomas Fishbourne, and

presented to Vadstena, likewise commenting on the Brigittine

Rule, attacking the corrupting indulgences, but written in such

a florid aureate Latin that it conceals more than it reveals of

community life. Both works are given in parallel text with

translation into English (rather than Swedish), and with textual

and explanatory notes, after an excellent introduction. The

source manuscripts are Uppsala University Library C74, C363 for

the <i>Responsiones</i> and British Library Arundel

11 for the <i>Collacio</i>.

Sadly, during the writing of this review I received a letter

from the former Abbess of Syon, explaining they are now closed

as an Abbey, the three remaining Sisters living quietly

elsewhere, their marble gatepost on which a part of St Richard

Reynolds’ quartered body had been placed, given away. Younger

branches of Brigittines, nuns and monks, however, continue

worldwide.

Reviewed by Julia Bolton Holloway

University of Colorado, Boulder

holloway.julia@tiscali.it

Denise Nowakowski Baker. Julian of Norwich's Showings: From Vision to Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-691-03631-4. xi+215 pp. Bibliography, Index.

A young scholar's book, and perhaps the one which most profoundly discusses the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius and other Patristic material upon Julian of Norwich's Showings. Yet its thesis could have benefitted from even greater scholarship, combining its theological study with that of paleography and codicology, questioning its own thesis about the development of 'From Vision to Book'. An investigation of the Amherst, Westminster, Paris, Sloane and Stowe Manuscripts themselves of Julian's text of the Showings, or of their contexts, or of both, seriously undermines the standard assumption of Julian's textual development, of Vision, then Short Text, then Long Text, all of which is the premise of this particular book. Princeton University Press 'spams' the Internet with this book rather annoyingly!

One hopes Denise Baker will continue to write on Julian of Norwich, deepening her insight through the study of Julian in her medieval context, as well as that of the patristic world.

Frances Beer. Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love, Translated from British Library Additional MS 37790; The Motherhood of God, an Excerpt, Translated from British Library MS Sloane 2477, with Introduction, Interpretive Essay and Bibliography . Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1998. The Library of Medieval Women. ISBN 0 85991 453 4. viii + 93 pp. Bibliography and index.

Frances Beer had already edited the Amherst Manuscript Short Text of Julian of Norwich's Showings, from British Library Additional Manuscript 37,790, excellently, publishing that work in 1978, with Carl Winter of Heidelberg. This introduction and translation gives both that text and an excerpt from British Library Sloane 2477 on the Motherhood of God. Throughout, Frances Beer acknowledges the pioneer editing carried out by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. She observes that the Short Text is a fine introduction to Julian studies.

Like most modern scholars, though not earlier ones, Frances Beer considers the Short Text early, the Long Text late and the work of Julian's 'greater spiritual maturity'. (Yet she puts the XVI Showings of the Long Text, into the Short Text's 25 chapters, indicating these in square brackets, as if the XVI Showings' structure already existed at the time of the supposed earlier writing.) She adheres to Julian as having participated in Benedictine contexts, which Sister Benedicta Ward, S.L.G., denies. She carefully notes Augustine and Dionysius on mystical experiences as used by Julian. She also discusses the Ancrene Wisse cluster of texts, Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton and the Cloud of Unknowing cluster of texts in relation to Julian. (In this last instance the bracketed citation to 'Johnston' has one hunt in the Bibliography to find 'Johnson' given as translator of The Cloud of Unknowing, the reference being to William Johnston, S.J.; likewise 'Sara McNamer' p. 74, versus 'McNamer, Sarah', p. 86, both of which can be corrected in a subsequent printing. ) She discusses the careful attention given to autobiographical detail characteristic of the Short Text, and elaborately plots out the correspondences between the two versions. But she does not mention or study the second earliest Julian manuscript, that of Westminster , which again is different from the Short or Long Texts, and likewise a fine introduction for students to Julian, concise, yet giving the hazel nut/Nativity/Annunciation scene, God in a circle and as 'I it am' and the entire presentation of Jesus as Mother.

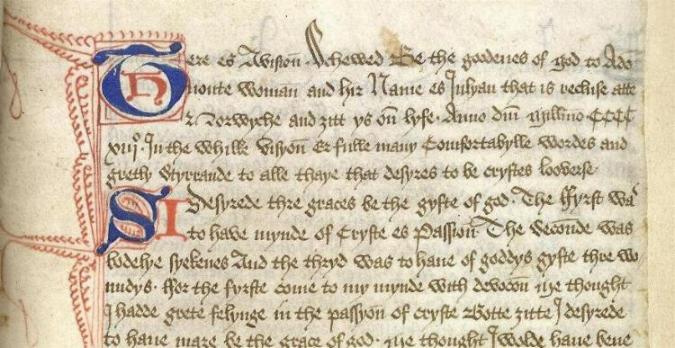

Francis Beer's translation begins with the head note about Julian being alive in 1413 at the time of the text's writing. She footnotes that statement to say it is not the date of composition but the year in which this copy was made. Yet the Amherst Manuscript begins, in the same hand, with texts dated as written in 1434 and 1435, and which are Richard Misyn's translations of Richard Rolle for the anchoress Margaret Heslyngton. The possibility Julian could have written or dictated this text when she was seventy is not entertained at all. The next footnote is to the 'paintings of crucifixes', noting that Norwich had fine wall paintings, but not discussing Archbishop Arundel's stress upon worshiping painted rood screens in churches as indicative of orthodoxy in this later period. The footnote to St Cecilia could have noted that the Norwich Benedictine, Adam Easton, friend of Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena, was Cardinal of the Basilica of St Cecilia in Rome, and by 1413, buried near St Cecilia's tomb. It was in this period also that Archbishop Arundel sternly forbade laypeople, especially women, from teaching theology and reading the Bible in the vernacular. In a note Frances Beer discusses Nicholas Watson's arguing for a later date for the Short Text.

The translation is excellent and a labour of love. As one reads it one is struck again by Julian's brilliance and compassion. A similar note to 'I it am', here translated 'It is I', could have been given on the order of that for 'reparation' as having been 'aseth'. For Julian's 'I it am' transcends gender yet stresses presence, oneness; the modern rendition changing the 'I am' of God into 'it is' thus branching away from Julian's stress upon the Hebrew meaning of God's name.

This shall be a fine volume to put into

students' hands. But could Boydell and Brewer reconsider the

cover? It presents four faces taken from different periods and

different countries, one an angel, the others of women, as a

quatrefoil upon black. Excellent for the Short Text would have

been the Crucifixion from the Despenser Retable in Norwich

Cathedral. It and Julian's coeval writing belong together.

I remember first reading Julian's Way: A Practical Commentary on Julian of Norwich in St Deiniol's Library in Wales and being entranced by it. In my poverty I am afraid I shamelessly begged Sister Ritamary Bradley for a copy. I here attempt to repay a debt

Ritamary Bradley, having given on its cover a painting of a wise woman, book and medicinal jars at hand, begins with the paradox that the practical mystic is the one who is the real mystic, while the one who studies mysticism theoretically remains outside of its hermeneutic circle of meaning.

Ritamary Bradley brings to her reading of

Julian profound depths of theology and poetry, ancient and

contemporary. A subtle, unacknowledged, and splendid agenda is,

of course, that in Julian's Way we have a woman writing

on a woman writing on God. Because the context of both women,

the one in the fourteenth, the other in the twentieth, is that

of monasticism, being oned with God, the first as authorial

anchoress, the second as professor and nun, this subtle

awareness works. It has all the openness and humility of Mary at

prayer, and of her Magnificat. Quietly, the title takes over as

Julian and Ritamary together live theology, not merely study it,

and with their words the reader too is swept up into the circle

of Wisdom.

Martin Buber. Ecstatic Confessions: The Heart of Mysticism. Ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr. Trans. Esther Cameron. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996. The Martin Buber Library. ISBN 0-8156-0422-X. xxxv + 160 pp. Bibliography.

I am asked to review this book for 'Mystic-L: Academic Discussion of Mysticism', and I realize that in that context both this book and I transgress boundaries. In Academicism the first person is expunged as being too emotionally involved to see issues objectively and clearly, and such writing, such study, is condemned as the 'personal heresy'. In my work on medieval pilgrimage poets I have discussed how the presence within the poem of the poet as pilgrim, as with Brunetto Latino, Dante Alighieri, Juan Ruiz, William Langland, Geoffrey Chaucer, Christine de Pizan, creates a sacred paradigm in which what is said in the first person of the poet is mirror-reflected within the soul of the reader of the poem, engendering mystical experiences shared by writer and reader. Similarly, for this ecumenical collection of first person mystical experiences collected and introduced by Martin Buber, the reader finds him/herself gazing into first the kindly eyes of the editor himself, pictured on the paperback cover, then into the souls of the writers whom he bares in this text. This book is a living confession with God and neighbour, of 'I and Thou', across time, space, religion, gender, death itself.

Paul Mendes-Flohr's brilliant introduction tells us that Martin Buber's Ekstatische Konfessionen was first published in an exquisite art volume in 1909. Martin Buber's doctoral dissertation had been on individuation in Nicholas of Cusa and Jakob Böehme, then, following a study of Jewish mysticism, he had also worked in Chinese, Finnish and Welsh literatures, including the Kalevala, the Mabinogion. Martin Buber in general translated his selections himself, Esther Cameron translating these likewise from his German into our English. Martin Buber's own introduction interrupts itself with the story of St Bernard's sermon interrupting itself while it was being preached, to confess in first-person ectasy, '"When I gazed out, I found it beyond all that was outside me; when I looked in, it was further in than my most inward being. And I recognized that what I had read was true: that we live and move and are in it; but he is blest in whom it lives, who is moved by it.'"

Martin Buber's Selections from Ecstatic Confessions, which repeat in a myriad ways Bernard's ecstatic confession, begin with Indian mystics, then Sufi, for whom the only example is the woman Rabi'a, Greek, then European monastic mystics, such as Hildegard von Bingen, the Franciscans, Mechtild von Magdebourg, Mechtild von Hackeborn, Gertrud von Helfta, Heinrich Seuse (Suso), Cristina and Margareta Ebner, Adelheid Langmann, a song attributed to John Tauler, entries from the German Sister Books, many of these from the convent of Töss written by Elsbeth Stagel, Suso's friend and supporter, Birgitta of Sweden, Julian of Norwich, Gerlach Peters, Angela of Foligno, Catherine of Siena, Catherine of Genoa, Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi, Teresa de Jesus, Anna Garcias, Armelle Nicolas, Antoinette Bourignon, Jeanne Marie Bouvieres de la Mothe Guyon, Elie Marion, Jakob Boehme, Hans Engelbrecht, Hemme Hayen, Anna Katharina Emmerich, with a Supplement of selections from the Mahabharatam and from Chinese and Jewish mystics, from the Church Fathers as mystics, and from the 'Sister Katrei' ascribed to Meister Eckhart. That the entries may be so heavily overweighted on the distaff side is likely due to women's exclusion from university training, and thus, as with monastic men, being drawn more purely from lectio divina , from contemplative practices. Strangely the volume lacks the major exemplar, Augustine's Confessions. But then so does Dante's Commedia.

Though first published almost a hundred years ago this book is both mint-new and transcends beyond the bounds of time. Unerringly Martin Buber has chosen the best passages both for himself and for us, in a marvellous generosity. Let me select from his selections from Julian of Norwich's Showings:

Because of the great, infinite love which God has for all humankind, he makes no distinction in love between the blessed soul of Christ and the lowliest of the souls that are to be saved . . . . We should highly rejoice that God dwells in our soul and still more highly should we rejoice that our soul dwells in God. Our soul is made to be God's dwelling place, and the dwelling place of our soul is God who was never made. [XIV.liv.113]

God is much closer to us than our own soul, for he is the ground in which our soul stands. [XIV.lvi.118]

Our Lord

opened my spiritual eye and showed me my soul in the middle of

my heart, and I saw the soul as wide as if it were an infinite

world, and as if it were a blessed kingdom. [XVI.lxviii.143v]

Robert H. Calderwood. Julian's Challenge. New York: Vantage Press, 1995. ISBN 0-533-11143-9. 102 pp. Appendices, Bibliographies.

This book came to me from Stella Maris, from two Anglican Hermits closely associated with Roman Carmelites, in the wilds of Canada.

The book is written by a male Anglican clergyman who delights in Julian's Wisdom of God as Mother and Wisdom and in her cherishing of the sacredness of the 'person' in relation to the cosmos. He places Julian of Norwich in the context of modern feminist theology and current issues, such as abortion, and he employs strategies similar to Julian's own, presenting arguments 'doubly', giving both what is acceptable and what is challenging, allowing the two sides of the debate full play against each other, while omitting his own determination concerning them, a strategy Julian had needed to employ in her day.

I was concerned to find on page 75 that Rev. Robert H. Calderwood gives the Hebrew for Wisdom as 'Hokinah'. Had he given his printer or typist a manuscript with 'Hokmah ' and not adequately proofread the text? Or is the error his own? I quibble over these jots and tittles, because he is right where he sees that Julian had had 'well-learned cleric tutor', p. 2. Julian's Master and Rabbi was likely the Norwich Benedictine, Oxford Master, and Roman Cardinal Adam Easton, whose Hebrew was better than that of St Jerome, the translator of the Vulgate Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin. For the Lady Julian displays a better knowledge of the Hebrew Bible than does the clerical writer of this book. This is not Rev. Robert H. Calderwood's fault so much as it is that of the Church of England, which is the one Lutheran Church that has officially abandoned the study of Hebrew and Greek for priestly ordination.

The author of this study is right to see that 'shalom' in its sense of wholeness, wellness, peace, is a concept in Julian's vocabulary of ideas. With only a little further study the book's author could have recognized that phrase, 'Shalom' 'All is well', 'And all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well' as from 2 Kings 4. 23, 26, where it is used concerning Elisha and the raising of the dead child of the Shunamite woman, at first with the greatest sarcasm, then the word coming into its true and peaceable meaning.

I had treasured that use by Julian of 'Shalom', for it embodies the grief, then joy, not only of the Shunamite, but of her Syro-Phoenician counterpart, and of the widowed mother of the dead son at Nain, and of Mary's own loss of her cherished son to the Roman soldiery's cruelty in Jerusalem, followed by Easter joy. Then, the other day, at an old Carmelite monastery here, now inhabited by Australian nuns, I looked at the frescoes, realising that one is of Mount Carmel and of Elisha and his raising of the dead child. We know that Julian not only had Benedictine associations but that also Margery visits her straight after talking with a saintly Carmelite in Norwich, William Southfield, who had likely sent Margery on to Julian for counselling and consoling.

Though Rev. Robert H. Calderwood's book is somewhat loose in its structure, and perhaps too careful in not giving an opinion to issues that it raises, it does point to another area in which Julian's wisdom can console: to the parents of dead, even aborted, children, who carry with them a haunting burden of guilt, blame, and sorrow. In this Rev. Calderwood is not unlike his predecessor, the saintly Norwich Carmelite William Southfield, who understood that women are in need of the wise counsel of women.

The Cloud of Unknowing. Ed. Patrick J.

Gallacher. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University,

1997. TEAMS: Middle English Texts. ISBN 1-879288-89-3. ix + 132

pages. Introduction, Bibliography, Text with Textual Gloss,

Notes, Glossary.

The Middle English Texts Series is designed for classroom use, making available texts adjacent to the readily available classics by Chaucer, Langland, the Pearl Poet and Malory. The Cloud of Unknowing is already available in an excellent edition by Phyllis Hodgson for the Early English Text Society, Original Series, 218, and thus shelved in most academic libraries. But the present edition has an excellent introduction placing the Middle English text in the context of mystical theological writings, Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite , the Victorine, Thomas Gellus and the Carthusian, Hugh of Balma, an up-to-date, though brief, bibliography. Its text, presented without the Middle English manuscripts' thorns, yochs, and italicized contractions, makes for easier reading for the undergraduate student. It is pleasing that the editor chose to bold the chapter headings, which the EETS editor had not done. Medieval manuscript scribes took care to differentiate their scripts by engrossing, bolding or rubricating in this manner.

Phyllis Hodgson consulted all manuscripts but chose as base text one that did not reflect East Anglian/Scandinavian area characteristics. Similarly the three manuscripts Gallacher consulted do not come from those families. The manuscripts of those families tend also to include 'doctrine schewyde of god to seynt Kateryne of seene [Catherine of Siena ]. Of tokynes to knowe vysytacions bodily or goostly vysyons whedyr thei come of god or of the feende'. Neither Hodgson nor Gallacher comment on the probable gender of the recipient of this and its related texts. A lively literature had grown up in the British Isles and elsewhere in which men counseled women how to live the anachoritic or enclosed life. Where they did so to fellow men they wrote in Latin. But to women they wrote generally in the vernacular, referred to both 'men and women' in their examples, and cited scriptural texts concerning women. All this the Cloud Author likewise does in his texts. The Cloud Author is himself shrouded in a cloud of unknowing. But there was a Norwich Benedictine, Adam Easton , who taught at Oxford University, became Cardinal of St Cecilia in Trastevere, defended St Birgitta of Sweden' s canonization on the basis of her visionary writings, the Revelationes, who also knew St Catherine of Siena and the spiritual director to both women, the Bishop Hermit, Alfonso of Jaén, whose text on spiritual discernment was copied out in its own right into Middle English in a Norfolk manuscript, as well as being restated in the Cloud Author's Epistle, and being repeated in Julian of Norwich's Showing.

Adam Easton wrote many works, some extant, others lost. Among those which are lost is a Treatise on the Spiritual Life of Perfection and various other texts in the vernacular. Besides all of which Adam Easton, O.S.B., when preaching to the laity in Norwich and later, owned and intensely used a thirteenth-century manuscript of Pseudo-Dionysius ' Works, now at Cambridge University Library. Its prayer invocation to the Trinity in the Mystic Theology has a most beautiful Gothic T intertwined in green and gold leaf. That invocation the Cloud Author feminized for his recipient, having the Trinity become the Sovereign Goddess Wisdom, where he translated that text in Dionise Hid Diuinite. He had also addressed her in the opening of the Cloud of Unknowing as the Bride of Christ, language frequently used of anchoresses and by Saints Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena. It is just possible that the Cloud Author and the Cardinal are the same person. It is even just possible that he wrote for a Norwich anchoress who may have once been herself a Benedictine at Carrow. St Julian's was under Carrow's Benedictine Priory, which in turn was under Norwich Cathedral's Benedictine Priory. Again and again reading the texts of Julian of Norwich and of the Cloud Author one comes across the same words, oneing, noughting, sovereign, and the same concepts. Especially these swirl about the feminizing of the Trinity, of God as Mother. Likewise the Prologue to the Cloud is echoed in the Envoi to the Sloane Manuscripts' Showing.

This review, in a shorter version, is appearing in Arthuriana, which graciously gives permission for its republication.

Membership in the International Arthurian Society-North American Branch, and its Journal, Arthuriana, may be obtained by writing to Professor Joan Grimbert, Department of Modern Languages, Catholic University, Washington, DC 20064.

Marion Glasscoe. English Medieval Mystics: Games of Faith. London: Longman, 1993. xii+359 pp. ISBN 0-582-49517-2. Bibliography, Index.

Reviewed originally for Medium Aevum.

The Virgin at the Annunciation , when told of the Word become Flesh, was often shown as in the act of reading, and as reading Isaiah's contemplative prophecies concerning the Messiah. St Augustine in his Confessions spoke of his conversion wrought through a child's voice, as if in play, telling him to take up a book and read. Marion Glasscoe has written such a playful book about books of contemplation, games of spirituality, for us to take up and read. She studies in turn (and closely studies their texts), fourteenth-century Richard Rolle and Walter Hilton writing for women recluses, the unknown author of the Cloud of Unknowing writing supposedly for a Carthusian novice, and East Anglian Julian and Margery's books of showings of revelations, written for women and men everywhere.

Marion Glasscoe has access to important materials, her University of Exeter having inherited the Syon Abbey library of Brigittine books: Danzig/Gdansk, to which Margery went on pilgrimage, was and is a major Brigittine pilgrimage shrine; St Birgitta's marriage to Christ was the model for Catherine of Siena and for Margery Kempe. This study could have discussed the pattern in which books self-referentially prompt books, engender books, for instance St Birgitta's Revelationes as model for Julian and Margery's Showing and Book.

Marion Glasscoe has written a finely detailed book on the English Mystics, playfully harnessing for her purpose T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets as touchstone and some, but not all, modern critical theory. One can read this book as a scholar, or one can read this book as a contemplative, and, in either category, gain from it a fresh vision of the authors and texts it discusses.

Its extensive and careful use throughout of

manuscript texts is of great value (though it omits the

Wesminster Cathedral Julian Showing manuscript). The

typesetting is sometimes difficult to read. The cover design,

with the Virgin at the Annunciation from Thomas Boleyn's

alabaster tomb in Wells Cathedral, repeated again on the book's

spine, is excellent and well encloses this timely book.

Hilton, Walter. The

Scale of Perfection. Edited by Thomas H.

Bestul. TEAMS: Middle English Texts Series.

Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. Pp.

vii + 289. $18.00 (pb). ISBN 15804406801.

Reviewed, June-Ann Greeley, Sacred Heart University, greeleyj@sacredheart.edu

The image of Western Europe in the fourteenth century has been properly etched in modern consciousness as a civilization trembling into disarray from the successive shocks to the contemporary ethos. Familiar cultural patterns, social traditions, and essential assumptions about truth and reality, were continuously disturbed throughout the century, and thereupon often transformed with the accretion of change. Certainly all civilizations experience challenges to established norms, and all civilizations respond to such challenges according to different strategies: by rejecting out of hand any changes that might emerge; by adopting certain aspects of some changes while decrying others; and, finally, by fully absorbing such transformations into the existing patterns and parameters of culture. Fourteenth-century Europe, however, witnessed a civilization in such broad disarray that it seemed perched on the very edge of final dissolution. The disquiet was a widespread social and spiritual disorder that reached into every village and city of Western Europe. Although the history of the period may be overly familiar, a few critical events bear repeating.

From 1337 until well past the turn of the fifteenth century, the Hundred Years War ravaged the nations of England and France, and caused not only carnage to peoples and places, but gradually corrupted as well the human spirit with despair and cynicism. Within a decade after the inception of the Hundred Years War, the Black Death began its gruesome stalking of Europe, and before it settled into its tentative dormancy by the 1360s, it had consumed nearly a third of the total population of Europe. Moreover, the plague had so savaged the populations of cities and villages that, in many places, a brutal lawlessness and general disregard for order reigned. Such dissolution of accustomed standards and the blatant rejection of traditional figures of authority had impetus from another catastrophic disturbance to the societal structures and religious parameters of the fourteenth century. The spiritual edifice that was Rome was crumbling before the stunned gaze of the faithful. Early in the century, the papacy had suffered the grievous humiliation of the "Babylonian Captivity" in the dislocation of the papal court to Avignon. Thereafter, in the latter quarter of the century (in fact, until 1417), western Christendom staggered under the onus of what would be known as "the Western Schism," the implausible horror of the Church enduring the presence of two popes: the lawfully (although, subsequently, for many of the cardinals, regrettably) elected Urban VI and, by 1378, the more compliant, yet finally moot, Clement VII of Avignon. The schism thrust many believers into a spiritual confusion and a hardened distrust of ecclesiastical process that eventually emerged as desperate complaints for reform, as well as open challenges to papal authority, and for some, to the very legitimacy of the papacy. A noxious chill of fear and bafflement crept through and among the peoples of Western Europe in the fourteenth century and addled despair to the soul of a civilization already besieged with too many disturbances.

In addition to the general discord of the time, England suffered as well from her own particular set of troubles. During the course of the fourteenth century, two anointed monarchs of Great Britain (Edward II, d. 1327, and Richard II, d. 1399) were deposed, imprisoned and murdered; moreover, throughout the century, there were significant episodes of political intrigue and competition, social unrest, and class hostility that troubled the governance of the realm. Smoldering resentment of the imperial rule, notably that of the Commons with the royal courtiers, resulted in louder voices of rebellion against and impeachment of the authority of the throne. Adding a bitter sting to English woes was the persistence of Scotland, under Robert the Bruce and later under his son David, in its bid for independence; throughout the century, Scotland continued to worry England, especially in the villages of her northern border. In 1381, sparked by the final insult of the levying of a poll tax on a population already fueled with angry discontent and unrest, the common people of England erupted into the Peasants' Revolt, propelling a stormy mob of frustrated commons towards London and towards the hapless young King Richard II. However, it was not only in the political arena that the general populace felt betrayal, disconnection, and frustration. Among the faithful in England, there had been a growing discontent with the power and wealth of the clergy and, in 1327, as the monarchy was overthrown, so also were both Bury St. Edmunds and St. Albans abbey the scenes of mob violence and attack. Yet dismay with the church reached far more deeply than the secularized affairs of the clerical hierarchy. A robust movement for ecclesiastical and theological reform took hold of English souls; indeed, the rise of John Wyclif and the Lollards, England's first 'real" heresy, can be considered a response to the troubling disorder and anarchy and confusion of the times. The fourteenth century in England then, as throughout Europe, was a time of turbulence, awakening, fearsomeness, fearfulness, and possibility. It was in this world in which Walter Hilton lived and wrote.

Walter Hilton, like his European contemporaries Johannes Tauler, Henry Suso, and Catherine of Siena, and his countryfolk Richard Rolle, Julian of Norwich, and the anonymous author of the Cloud of Unknowing, responded to the general social unrest and religious dissatisfaction by turning away from the public, ecclesiastical forms of Christianity, and toward the more affective tradition of Christianity, the interior path of the mystic that relies upon personal reflection and private contemplation for spiritual nourishment and enlightenment. While never divorcing themselves officially from the Church and from the essential doctrine of Church teachings--indeed, most remained steadfastly committed to the authority and primacy of Rome--the mystics of the fourteenth century opted for a spirituality as old as Christianity itself, yet roundly discounted by ecclesiastical authorities and influential schoolmen as bending too far from approved church structure and, therefore, from the necessary direction of the ordained clergy. Still, impassioned mystics like Rolle and spiritual directors like Walter Hilton encouraged the validity of personal devotion, and wrote treatises that posited the interior life of the individual believer as an authentic locus of salvation. They insisted that the pedantic intellectualism of the schools were insufficient to sustain the life of the spirit, and must be enriched by a program of humble penance, devout prayer, and loving contemplation of the person and the passion of the Christ. Only through an active participation of the spiritual faculty in Christ, they emphasized, can an individual achieve the full measure of a meaningful existence. Hilton himself wrote that:

Jhesu is tresoure hid in thi soule; thanne yif yow fynde

myght Hym in thi soule,

and thi soule in Him, I am siker

for joie of it thou

woldest gyve alle the likynges of alle

ertheli thinges for to

have it. Jhesu slepeth in thyn

herte gosteli...Doo

thou so stire Him bi praiere and waken

Hym with criynge of

desire,and he schal ryse sone and

helpe thee. (I, 49,

1437-1442)

As the Hilton excerpt indicates, the use of the vernacular was fundamental to the intent of the spiritual guidance, for texts written in the contemporary language of the people would be available to a more broadly based and more diverse audience than if they had been written only in the traditional Latin. In fact, by the fourteenth century, it was quite likely that few prelates in England, except those in the highest clerical ranks, and even fewer lay people, with the obvious exception of illustrious scholastics, were thoroughly conversant in Latin. Therefore, in order to facilitate its access by both clerical and lay devotees, a book of spiritual direction such as the Scale would find its widest distribution if it were composed in the language of the people. A treatise that instructs the faithful how best to pray should, reasonably, be in the language in which the faithful will pray.

To their great credit, Thomas Bestul and the TEAMS committee have provided both students and scholars with an edition of Walter Hilton's Scale of Perfection in its original Middle English, and the distinctions in tone, idiom, meaning, and affect between the many modern English "translations" and the authentic ME text are remarkable, to say the least. With the turn of each page, the text and its author, and the fourteenth-century panorama of faith and spiritual practice, come to life as never a modern reading would be able to capture. In addition, Bestul has wisely provided the modern reader with both a linguistic apparatus of modern English, on the bottom of each page, for those words and phrases that are the least accessible or intelligible to the modern idiom, as well as an abbreviated but quite welcome glossary of about 150 of the most frequently cited words. For those readers of Scale who are not scholars of Middle English dialects or medieval English literature, such as scholars of religious history or medieval spirituality, the availability of such critical details will prove invaluable in making use of the TEAMS text. Also for novices to the intricacies of fourteenth-century English Christianity, Bestul has appended to the fourteen page Introduction a five page "select" bibliography which affords the student fundamental sources and secondary references for further study of Hilton and his works. The bibliography is serviceable, but somewhat dated, and should not be considered (nor does it claim to be) an exhaustive review of Hiltonian studies; nevertheless, it offers the reader new to Hilton's Scale essential secondary references to Hilton, his works, and the context of medieval English mysticism.

Still, the author

of Scale endures as a shadowy figure in the realm of

medieval writers. Little can be actually verified about

the life of Walter Hilton-- which is, as one suspects, as he

preferred. It is generally accepted that by 1375 or so, he

was a canon of the Augustinian Priory of Thurgarton in

Nottinghamshire; it is also likely that, much prior to his

residence at the Priory (where he continued to live until his

death in 1395/96), he had been a student of theology at

Cambridge. Less verifiable, but not at all unlikely, is

the speculation by some scholars that Hilton himself had, at

some point, led an eremitical life, a life not dissimilar from

the one led by the anchoress whose need for spiritual counsel

formed the pretext for the composition of Scale.

While there is no proof of that possibility, the text itself

does evidence an authentic ease with and clear-sighted

understanding of the spiritual life of a solitary, as well as a

keen regard for the psychological and physical complications

that trouble the isolated pilgrim. Whatever the facts of

his life, Hilton's Scale of Perfection is known to have

been one of the most popular spiritual texts in late medieval

England, as the number of extant manuscripts (about

forty-five) demonstrate. It was translated into Latin by

about 1400, and it was that Latin version that soon found its

way to Europe, particularly among communities of (male and

female) Benedictines and their more ascetic brothers, the

Carthusians. In England, the original Middle English tract was

copied and "amended" over successive centuries, with the

result that no one manuscript can claim primacy. For the

TEAMS volume, Dr. Bestul selected a fifteenth-century

manuscript from Lambeth Palace, London, MS 472. This

manuscript is, in fact, a collection

of works by Hilton, including Eight Chapters on Perfection

and Mixed Life, as well as Scale.

Bestul

notes (8) that the Lambeth manuscript he used is interesting for

reasons apart from its contents. MS 472 exists, in fact,

as an example of a fifteenth-century "common profit" volume,

that is, a manuscript incorporating several spiritual writings

and works of religious counsel that was commissioned by a lay

person (in this case, one 'John Killum, grocer') hoping to

enrich his/her life of faith, and the lives of those descendents

to whom the original owner later bequeathed the manuscript.

The textual history of the Scale is complicated not merely by scribal emendation, or geographical and cultural variance. At some later date from the initial publication, Book One of the two-book Scale seems to have undergone a revision, an embellishment of the original text with a more personal Christology, with the result that at least two versions of Book One of the Scale are extant. Some scholars suggest that Hilton himself may have revisited his work, in his later and, possibly, wiser years, and altered the text himself; however, most scholarship rejects that claim and prefers to attribute the apparent changes in language and focus to the deliberations of zealous scribes. Nevertheless, it is indeed a testimony to the fluidity of the treatise, in consonance with the spiritual journey it delineates, that Hilton (purportedly) advised his readership that, "thise wordes that I write, take hem not to streiteli, but there as thee thenketh bi good avysement that I speke to schorteli...I prey thee mende it there nede is oonli" (Scale, I, 92). Hilton understood that the spiritual advice he was providing would probably not be effective simply as a fixed manual of instruction, but must be able to evolve continually as the context and culture demanded.

That Hilton's work today no longer enjoys the popular esteem in which it was held in its own time is due in no small part, it seems, to the proclivity of the modern age to be overly impressed with Richard Rolle's mystical passion or to be absorbed by Julian of Norwich's evocative examination of her vibrant "showings." Walter Hilton's style is one which bespeaks a teacher: deliberate and considered, almost placid in its order and rationale, and generous in its broad applicability, notably to the laity. Written ostensibly to a cloistered anchoress who sought from him guidance in her chosen devotion to the contemplative life, Hilton's Scale of Perfection opens with a tacit recognition of the universal application of its rationale: one must embark upon the interior journey of spiritual perfection because

...a wrecchid man or a woman is he or sche that leveth al

the inward kepinge of

hymself and schapith hym withoute

oonli a fourme and

likenes of hoolynesse, as in habite and

in speche and in bodili

werkes... wenynge hymsilf to be

aught whanne he is

right nought, and so bigileth hymsilf.

Do thou not so, but

turne thyne herte with thy body

principali to God, and

schape thee withinne to His

likenesse bi mekenesse

and charite and othere goostli

vertues, and thanne art

thou truli turned to Hym.

(I,1)

Hilton asserts that it is incumbent upon every Christian to "turn" heart and body to God; each Christian, he insists, and not just those literally walled from society, enjoys the capacity of that turning (conversio) to God, which is the familiarly medieval paradigm of the ascent to the Divine. The activity of the ascent must be motivated toward the sure condition of authentic contemplation, which Hilton accords three parts aspects: the "knowing" of God and spiritual matters through study, instruction, and rational discussion of Scripture, cognition empty of true emotion, "unsavery and cold" (I, 4); the pure "affection" for God, most apparent among the devout who, though sincere, possess faith without "undirstondynge of gosteli thynges" (I, 5), and, thirdly, the contemplation of God that lies in both cognition and affection, "in knowyng and in perfight lovynge of God" (I, 8). However, such a contemplative state is, as Hilton says, like a "mark bifore the sight of thi soule" (I, 14), resting on a spiritual height that requires preparation for the soul for so lofty a climb. The individual must first work toward an inner transformation, a personal reformation of his/her condition of virtues, for, as Hilton laments:

(t)here is many man that hath vertues, as lowenesse,

pacience,...and siche

othere, onli in his resoun and wille

and hath no goostli

delite ne leve in hem...he doth hem by

strenghte and stirynge

of resoun for drede of God. This

man hath vertues in

resoun and in wille, but not the love

of hem in affeccion...

(I, 14)

Walter Hilton rightly distinguishes between the life of virtue based on reason and fear, which is, in fact, not true virtue at all and so would impede the journey to God, and the life of virtue based on affection and love, which is essential to aid the questing soul toward contemplation, and its final resting in God. The virtues to which he refers are common enough, although Hilton makes a particular point to emphasize meekness, spiritual patience, and purity of heart. Indeed, it is perhaps a cautionary reminder for the modern age that Hilton singles out "meekness," or humility, as the virtue upon which all others build, and the one to which all other tend.

This partie of mekenesse thee bihoveth for to have in thi

bigynnynge, and bi this

and bi grace schalt thou come to

the fulhede of it and

of alle othere vertues...(a)s mykil

as thu hast of

mekenesse, so mykil haste thou of charite,

of pacience, and of

othere vertues...(mekenesse) is the

first and the laste of

alle vertues...(d)oo thou nevere so

many good dedis,...yif

thu have no mekenesse it is nought

that thou doost. (I,18)

One cleanses and thereby strengthens the soul through the authentic inculcation of loving virtues, gifts of the Holy Spirit, a continuous process that does include activities commonly associated, but not exclusively, with the cloistered life, particularly study of the sacred w(W)ord (Lectio), meditation (Meditatio), and prayer (Oratio). Hilton centers true spiritual growth on meditatio and oratio especially, the one a thorough appraisal of one's character, faith life, and capacity for change, and the other a formal recognition of being ultimately helpless in the spiritual journey without being "touchid and lightned of the goostli fier which is God", which "lightening" occurs most at the core of prayer.

Book One of Scale, then, delineates quite carefully the arduous ascent to God by extolling the purification of the soul in stages, and, thereupon, by assessing the spiritual activities of study, meditation, and prayer, that ready the soul for loving contemplation of God. Book II focuses with greater clarity and even urgency upon the human soul as image of God, and the need for reforming one's soul corrupted and lost in sin and debasement. In Book II, Hilton acknowledges with the conviction of experience that such spiritual reform cannot be achieved by humanity itself, but must rely upon the abiding presence of Jesus Christ to affect change: "...for I wot wel that oure Lord Jhesu bringeth al this to the ende...(f)or He dooth al; He formeth and he reformeth. He formeth oonli bi Hymsilf, but He reformeth us with us..." (II, 28). The soul restored to its original condition of light in all its simplicity and love is then able to contemplate by means of grace the Love that is God/Christ, and so abide perfectly in eternal peace and joy.

Julia Bolton Holloway. Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden 's Revelations. Translated from Middle English, With Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Newburyport: Focus Texts, 1992; Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1998. xv + 164. Now Boydell and Brewer.

Of use for placing Julian's Showings

in her context of continental writings by women of Revelations,

including Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes. The text

translates a manuscript at Princeton University which originally

came from Syon Abbey, whose nuns also preserved Julian's texts,

in the Amherst, Westminster and Paris

versions. She was asked to write this book by Professor Jane

Chance, the series' editor, because of her previous work, The

Pilgrim and the Book: A Study of Dante, Langland and Chaucer.

Julian of Norwich. Showing of Love.

Translated by Julia Bolton Holloway. London: Darton Longman and

Todd, 2003; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2003.

Reviewed, JNL

The definitive scholarly edition of Showing of Love is here presented in a form for the general reader, without sacrificing academic rigour. One is able to flow into her mind, for, as far as possible, the rhythms, style and dialect of Julian's East Anglian English of c1400 have been retained. To have translated her slavishly into modern English would have negated that closeness with her experiences and meditations which we enjoy here. A twenty-seven page Preface provides more than adequate background information about Julian, her contemporaries, the theology she and they expound, and the history of the manuscripts used. The 'chapters' into which her meditations were divided, permit leisurely and profound 'lectio divina'.

Horrox,

Rosemary and Sarah Rees Jones, eds. Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities,

1200-1630. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2001. Pp. ix + 286. $60.00 (hb).

ISBN: 0-521-65060-7.

Reviewed, Jesse G. Swan University of Northern Iowa

jesse.swan@uni.edu

A festschrift, by definition, celebrates and honors a scholar

of immense noteworthiness by publishing, ideally, exceptional

essays by equally exceptional intellectuals on topics or

methods drawing on those of the honoree. Impressively,

Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones have accomplished this

with their volume for Barrie Dobson, Pragmatic Utopias.

As a practice of

interpretation, historical criticism is a matter of

reading. What is read and how one reads usually

distinguishes historians, and it is one of this volume's best

qualities to provide an ample complement of readings.

Accordingly, the volume presents essays that deal with

non-literary documents -- by far the bulk of the collection--

as

well as some that treat literary texts. Such a division

between literary and non-literary texts is not the editors'--

they organize the essays chronologically according to subject

matter-- but it highlights many important issues the book

engages, including the modern disciplinary division that the

honoree variously contributed to and sought to cross, the

different sorts of conclusions usually drawn from various

forms and genres, the value of crossing disciplines by

thinking of

individual texts in terms usually applied to other documents,

and, perhaps most suggestively, the possibilities available to

those who can advance from crossing disciplinary manners of

reading into transcending them.

Some essays express

overtly an anxiety over crossing lines, such as when, in

attempting to resolve the apparent "historical

paradox" of the decision of Hugh of Balsham, Bishop of Ely, to

found a college "not for his monastic brethren, but for

secular

clerks," despite his order's concern "to provide a university

education for its most promising young monks" (60), Roger

Lovatt denigrates the evidence of "tone and language" in favor

of "precise injunctions" (77), a methodological gesture that

removes him from paradox and places him in singular, if

qualified, conclusions, such as, "We can only say with

reasonable certainty that he founded in Cambridge an

independent college-- its independence perhaps forced upon him

against his better judgment-- for poor, secular scholars who

were to follow as appropriate the rule of Merton" (77).

Similarly pursuing "continuity and singleness" (175), Peter

Biller's "Fat Christian and Old Peter: ideals and

compromises

among the medieval Waldensians" deals with, in order

implicitly to reject, the records that remain-- they are only

"the views

of the extremists, the polemicists and the dreamers" (184)--

so as to propose a vision of most Waldensians as compromising

their ideals in order to continue as an order. Biller

writes that the "frustration is that there is only silence

from men of

probably middling views, such as Fat Christian and Old Peter"

(184), by which he means there is no document purporting to

report first-hand the views of these two dissenters, who are

referred to by others in the inquisitorial records.

Other essays draw on

various non-literary records in an effort to re-appreciate

experiences of groups of people or people's

experiences of certain late medieval and early modern

institutions. Janet Burton, in "The 'Chariot of

Aminadab' and

the Yorkshire priory of Swine," shows how, in "acting under

acute financial pressures," "the way in which [the prioress

and

nuns of Swine] responded somewhat redresses the picture of

medieval religious women as unable to act for themselves"

(38).

Burton accomplishes this by suggesting that the "evidence from

wine does not suggest that the canons were there in order to

occupy positions of authority, but rather to provide spiritual

succour and literacy" (37). Also taking finances to be

of

prime, real importance in defining significance, rather than

spiritual or academic "ideals," Malcolm G. Underwood's "A

cruel

necessity? Christ's and St John's, two Cambridge

refoundations" and R. N. Swanson's "Godliness and good

learning: ideals and

imagination in medieval university and college foundations"

compare the foundations to modern business and suggest how the

statutes for the universities are not prescriptions as much as

safeguards against economic difficulties. Also

addressing a

perceived problem with previous readings of records, but

addressing the issue of popular relations with the nascent

judiciary, Anthony Musson, in "Social exclusivity or justice

for all? Access to justice in fourteenth-century

England,"