♫

You can also open the sound

files of this essay, by clicking on the red arrows, or by

toggling back from Quicktime to this page by reducing but not

closing the audio file in order to experience the images,

written text, and sounds together: the Ambrosian hymn, Deus Creator Omnium, aug.mp3 (performed, Stirps Jesse, directed,

Giacomo Baroffio, included here with his permission),

|

Deus creator

omnium Artus solutos

ut quies Grates peracto

iam die Te cordis ima

concinat, |

Ut, cum profunda clauserit diem caligo noctium, fides tenebras nesciat et nox fide reluceat. Dormire mentem ne sinas, dormire culpa noverit: castos fides refrigerans somni vaporem temperet. Exutu sensu lubrico te cordis alta somnient, nec hostis invidi dolo pavor quietos suscitet. Christum rogemus et Patrem Christi Patrisque Spiritum; unum potens per omnia fove precantes, Trinitas. Amen |

♫

with this text read aloud,

augmyst.mp3. Even all three at once

can be called up and experienced on your computer in a sensual

medieval polyphony. Their manuscripts were read so, with

gold-leafed and splendidly coloured illuminations and the memory

for the reader of the music that went with the words.

Augustine,

The Confessions || Boethius, The Consolation of

Philosophy || Dionysius

the Areopagite, The Mystic Theology || Gregory on Benedict, Dialogues

|| Dante Alighieri, Vita Nuova, Commedia || Wisdom in the Bible

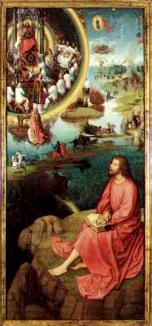

Hans Memling, 'St John

Writing Revelations', The Hospital of St John, Bruges,

Belgium

Reproduced with

permission from the Memlingmuseum, Stedelijke Musea

Brugge, Belgium

UGUSTINE, Aurelius Augustinus, was born in

Africa in A.D. 354 at a time when the Roman Empire was

crumbling. He grappled with the conflicting beliefs of that

uncertain era, coming to reject Neoplatonism and

Manicheanism for Christianity, being converted in a garden

outside Milan through reading Paul's Epistle. He had been a

Professor of Rhetoric, of Literature, he now professed

Christ, the Word. Edith Stein has

written a beautiful dialogue between Ambrose and Augustine

in her Three Dialogues. Augustine was baptised by Ambrose in

387. Returning to Africa he became Bishop of Hippo, dying as

the Vandals were besieging his beloved cathedral city. In

his Confessions

he writes his spiritual biography, much as Julian does

in her Showing of

Love. In it he explains that sin is the tending to

non-being, to diverging from God's Creation. In its Book XI Augustine presents a

heady discourse upon Time and Eternity, based upon Ambrose's

evening hymn. ♫

The entire Book XI is

given in an oral reading at augustine.mp3.

And so our discussion went on. Suppose, we said, that the tumult of man's flesh were to cease and all that his thoughts can conceive, of earth, of water, and of air, should no longer speak to him; suppose that the heavens and even his own soul were silent, no longer thinking of itself but passing beyond; suppose that his dreams and the visions of his imagination spoke no more and that every tongue and every sign and all that is transient grew silent - for all these things have the same message to tell, if only we can hear it, and their message is this: We did not make ourselves, but he who abides for ever made us.

The work is written in sections, divided between Prose and Poetry. Medieval manuscripts of the text are richly illuminated, presenting Boethius in prison, mourning on his bed, and visited by the Lady Philosophia, and from her Dante derived his consoling figure of Beatrice.

Book II, Poem 8 Philosophia: Love rules the earth and the seas, and commands the heavens.

Book III, Prose 1 Philosophia: I am about to lead you to true happiness, to the goal your mind has dreamed of. But your vision has been so clouded by false images you have not been able to reach it.

Poem 1 Philosophia: Just so, by first recognizing false goods, you begin to escape the burden of their influence; then afterwards true goods may gain possession of your spirit.

Poem 3 Philosophia: The only stable order in things is that which connects the beginning to the end and keeps itself on a steady course.

Poem 9 Philosophia: You [God] who are most beautiful produce the beautiful world from your divine mind and, forming it in your image, You order the perfect parts into a perfect whole.

Prose 12 Philosophia: Then it is the supreme good which rules all things firmly and disposes all sweetly (Wisdom 8.1). Boethius: I am delighted not only by your powerful argument and its conclusion, but even more by the words you have used. And I am at last ashamed of the folly that so profoundly depressed me. Philosophia: Then can God do evil? Boethius: No, of course not. Philosophia: Then evil is nothing, since God, who can do all things, cannot do evil. Boethius: You are playing with me by weaving a labyrinthine argument from which I cannot escape. You seem to begin where you ended and to end where you began. Are you perhaps making a marvelous circle of the divine simplicity? Philosophia: As Parmenides puts it, the divine essence, is 'in body like a sphere, perfectly rounded on all sides'.

Book IV, Prose 6 Philosophia: Consider the example of a number of spheres in orbit around the same central point: the innermost moves toward the simplicity of the center and becomes a kind of hinge about which the outer spheres circle; whereas the outermost, whirling in a wider orbit, tends to increase its orbit in space the farther it moves from the indivisible midpoint of the center. If, however it is connected to the center, it is confined by the simplicity of the center and no longer tends to stray into space. In like manner whatever strays farthest from the divine mind is most entangled in the nets of Fate; conversely, the freer a thing is from Fate, the nearer it approaches the center of all things. Therefore, the changing course of Fate is to the simple stability of Providence as time is to eternity, as a circle to its center.

Book V, Prose 6 Philosophia: Eternity is the whole, perfect, and simultaneous possession of endless life. The meaning of this can be made clearer by comparison with temporal things, For whatever lives in time lives in the present, proceeding from past to future, and nothing is so constituted in time that it can embrace the whole span of its life at once. It has not arrived at tomorrow, and it has already lost yesterday; even the life of this day is lived only in each moving, passing moment. But God sees as present those future things which result from free will. If you will face it, the necessity of virtuous action imposed upon you is very great, since all your actions are done in the sight of a Judge who sees all things.

Boethius Diptych

Boethius Diptych

Gothic Architecture, Norwich Cathedral

But Abelard, while a monk at St Denis, denounced Dionysius's identity as fraudulent. Meanwhile, the Victorines also discovered and used the Dionysian corpus of writings. Cardinal Adam Easton, the brilliant Benedictine of Julian's Norwich, owned the complete works of Pseudo-Dionysius, in a fine thirteenth-century manuscript giving some of the Greek text as well as all the Latin translation, the invocation to the Trinity being most beautifully illuminated with a gold-leafed, intertwined 'T' at folio 108v. That manuscript is today, Cambridge Ii.III.32.

Here is the Invocation to the Trinity:

Trinitas supernaturalis, et supraquam divina et supraquam bona theosophiae Christianorum praeses, dirige nos ad mysticorum oraculorum plus quam indemonstrabile, et plus quam lucens et summum fastigium, ubi simplicia, et absoluta, et immutabilia theologiae mysteria, aperiuntur in caligine plus quam lucente silentii arcana docentis, quae in obscuritate tenebricosissima plusquam clarissime superlucet, et in omnimodo intangibilitate atque invisibilitate, praepulchris splendoribus mentes oculis captas superadimplet.

Meanwhile, the Cloud of Unknowing Author (but whom I suspect to have been Adam Easton, the owner of this stunning manuscript), translated the Mystic Theology into Middle English as Deonise Hid Diuinite for a woman contemplative. To do so he converted the Trinity into an invocation to divine and feminine Wisdom.

Gregory on Benedict, The Dialogues

REGORY the Great (c.

540-604) wrote an account of the Life and Miracles of St

Benedict (c.480-547), casting these in the form of

Dialogues between himself and Peter, a fellow monk. In

these Dialogues there is a most moving account of

Benedict and of his twin sister Scholastica and how

she is able to force her brother to break his Rule and

stay over night at her convent at Subiaco so that they may

converse all night upon God. She prays to God for a storm

which he grants. Three days later she dies.

That account is followed by one of Benedict's vision of God as greater than all his Creation. He is standing in prayer at a window of a great tower, apart from his sleeping disciples, when suddenly there is a great light, greater than that of the sun. As he marvels he suddenly sees as it were the whole world collected into one ray of light before his eyes.

Gregory and Peter discuss that vision, Gregory explaining that to the soul who sees the Creator all Creation becomes small, 'animae uidenti creatorem angusta est omnis creatorem'. He goes on to explain that it is not that the world contracts, but that the soul, seeing God, expands above the world, becoming greater than itself. 'Quod autem collectus mundus ante eius oculos dicitur, non caelum et terra contracta est, sed uidentis animus dilatatus, qui, in deo raptus, uidere sine difficultate potuit omne quod infra deum est'. And he further discourses upon the interior light and that of the eyes in this vision. The male abbot has experienced Mary's Magnificat in his prayers. 'My soul doth magnify the Lord'. Smallness become largeness; darkness, light; humility, power.

Gregory's Dialogues was, of course, a staple in Benedictine circles. The lovely dialogue, within the Dialogues, of brother and sister was sung antiphonally on the feast day of Benedict and Scholastica by Benedictines, celebrating the breaking of their sacred Rule. And that served to make Benedict's following vision concerning prayer the more memorable.

Christina of Markyate refers to it, where she sees in a flash of light the whole world.

And Julian of Norwich refers to it - and especially in connection with the Virgin at the Annunciation and Nativity,

and with the hazelnut passage,

and then again and again fugally throughout her text.

For Julian, whose anchorhold at St Julian's

Church is under the Benedictines of Carrow Priory, who are

in turn under the Benedictines of Norwich Cathedral Priory,

is seeped in Benedictinism. It is possible that her

Benedictinism is taught her by the brilliant Norwich

Benedictine Adam Easton. It is

even possible that Adam Easton might be her brother, might

even be her twin. There is a medieval manuscript referring

to a devout person desirous to know God's wounds, whose name

is given as ' Mary Oestrewick'. Adam Easton so spells his own name in one

manuscript 'Adam Oeston ', the 'wick' of the Scandinavians perhaps

being changed by him to the 'town' or 'ton', more common in

other parts of England.

It is not likely that Julian was influenced by

Dante except, perhaps, through Cardinal Adam Easton,

who quotes from him in his own writings. What is important

is that they share the same principles derived from these

preceding mystic theologians, participating in a past

'Internet' of God's Wisdom. Common also to many of these

mystics, these Friends of God,

is the sense of drawing apart, as to Mount Tabor with

Christ, only to descend the Mountain again to be with all

people in God's image, to be both chosen and universal, to

treasure these things in their heart as had Mary, their task

to seek Wisdom, amongst women and amongst men, and with her

to be part of God's sweet ordering of the cosmos.

All these writers, Augustine, Boethius, Dionysius, Dante and Julian, are influenced by the Hebraic and feminine figure of God's Wisdom, God's Daughter.

Augustine. Confessions.

Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961.

Baker, Denise Nowakowski. Julian of Norwich's Showings: From Vision to Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy . Trans. Richard Green. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1962.

CETEDOC, CLCLT.

Cloud Author. Deonise Hid Diuinite and Other Treatises on Contemplative Prayer Related to The Cloud of Unknowing. Ed. Phyllis Hodgson. London: Oxford University Press, 1958. Early English Text Society, 231.

Dante Alighieri. Tutte le opere . Florence: Sansoni, 1981.

Jantzen, Grace. Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian. London: SPCK, 1987

Long, Asphodel P. In a Chariot Drawn by Lions: The Search for the Female in Deity. London: The Women's Press, 1992.

Nolan, Edward Peter. Cry Out and Write: A Feminine Poetics of Revelation. New York: Continuum, 1994.

Nuth, Joan. Wisdom's Daughter: The Theology of Julian of Norwich. New York: Crossroad, 1991.

Pseudo-Dionysius. The

Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibheid. New York:

Paulist Press, 1987. Classics of Western Spirituality.

![]()

| If you have used and enjoyed this page please

consider donating to the research and restoration of

Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery by the Roma and its Library through our Aureo Anello Associazione's account with PayPal: Thank you! |

![]()

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2022 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS

|| HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF

SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST

MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER||

CATALOGUE AND

PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||