This text is also an audio

book for which click on this red arrow: ♫

The

essay is based on the premise, not held by all Julian

students, that the Amherst Manuscript, as it itself declares,

presents a text written in 1413 and under Arundel's censorship

of women teaching, especially theology. It is dedicated to the

memory of my paleography professor, Jean Preston, who owned

two Fra Angelico side panels of the San Marco altarpiece which

present a pair of Dominican saints.

argery Kempe visited Julian of Norwich perhaps

before 1413 and later reported their conversations, thus

providing for us not only the early written texts we now

have, the Amherst, Westminster,

Paris Texts, but also an Oral Text, spoken just prior to

the time that the 1413 exemplar to the Amherst Text was

being written. Margery's Manuscript thus allows us to go

back to fifteenth-century East Anglia with, as it were, a

tape-recorder or an IPod. For this reason we present this

essay in an oral recording at soulcity.mp3

which can be read simultaneously with this text, giving

the various Julian and Margery texts, on the screen.

Julian functioned in her community much like a

psychiatrist, healing souls, that Greek word, in fact,

meaning 'soul doctor'. For the Middle Ages theology was

psychiatry, making use of the Book

of Job and of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy.

Julian helps heal Margery's soul, perhaps too by

suggesting the therapy of the Jerusalem pilgrimage and the

writing of the vast book of her travels, The Book of Margery Kempe.

Both the Amherst and the Butler-Bowden Manuscripts, of Julian's Showing and Margery's Book, are now in the British Library. This essay transcribes directly from the manuscript texts. The letter þ 'thorn' is the Middle English form for th, the letter 3, 'yoch', is g, y or gh, the median letter ∫ the scribal s. Contractions are spelled out in italics. The foliation of the manuscripts is cited, preceded by A for Amherst (the Julian Showing Manuscript in the British Library, Additional 37,790), W for Westminster (the Julian Showing Manuscript owned by Westminster Cathedral and on loan to Westminster Abbey), P for Paris (the Julian Showing Manuscript in the Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Anglais 40) which can all be retrieved from the edition by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway, published by SISMEL, Florence, 2001), and M for The Book of Margery Kempe (the Butler-Bowden Manuscript, now British Library, Additional 61,823, discovered in 1934, and retrieved from the manuscript rather than from the edition by Sanford Brown Meech and Hope Emily Allen, Oxford: Early English Text Society, 212, 1939, 1961). Letters and words rubricated here are so in the manuscripts. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_61823_fs001r

Margery has her scribes tell us (M, folio

21r)

Margery and Julian's conversation continues

Julian next is reported as citing her authorities, Paul and Jerome, to Margery, who perhaps misremembers one of them:

Julian next discusses evil:

Apart from the Hilton and Julian texts in the Westminster Manuscript, making this same point are other texts associated with Julian: Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 78v: . . . iusti sedes est sapiencie. ffor as ʃeith holy write the ʃoule of the ry3tful man or womman is the ʃee & dwelling of endeles wiʃdom that is goddis ʃone ʃwete ihe If we been beʃy & doon our deuer to fulfille the wil of god & his pleaʃaunce thanne loue we hym wit al our my3te; and likewise John Whiterig, Contemplating the Crucifixion; from Anima iusti sedes est sapiencie: Proverbs 10.25b; cited, Gregory , Hom. XXXVIII in Evang. PL 76, 1282.

With that last comment, '& ʃo I truʃt, ʃyʃter, þat 3e ben', we realise that we are certainly listening to reported speech and that Dame Julian addressed Dame Margery, her 'evyn cristen', even as 'Sister'. The discussion of evil reminds one more of William Flete's Remedies Against Temptations than it does of Julian's 'sin as nought'. Interestingly, this phrasing concerning the soul as a city is closer to that of the Sixteenth Showing in the 1393/1580 Paris Manuscript, P143v-145v, and the 1413/1450s Amherst Manuscript, A112, which both give vestiges of the Lord and the Servant Parable, with their echoes from Angela of Foligno and Catherine of Siena, than it is to the earlier version, the Fourteenth Showing, present in the Westminster, W101-102v, and Paris, P116-119, Manuscripts.

liance þer with:

It behouyth

to ʃeke into

oure lord god in

whom it is

encloʃyd. And an=

nentis oure

ʃubʃtance it may

ryghtfully be

called our ʃoule.

and anentis our ʃenʃualite

it

may ryghtfull

be called our

ʃoule. and

þat is by þe

onyng

þat it hath

in god. That wur=

ʃhypfull cite

þat our

lord ihesu

ʃyttith in.

it is our ʃenʃualite.

in whiche he

is encloʃed. and

our kyndely

subʃtance is beclo=

ʃyd in ihesu criʃte. with þe bleʃʃed

ʃoule of

criʃte ʃyttyng in reʃte

in þe godhed.

And I ʃawe ful

ʃurely þat it

behouyth nedis

dalliance

therewith, it is right to seek into our lord God

in whom it is enclosed. And then our substance

may rightfully be called our soul, and then our

sensuality may rightfully be called our soul,

and that is by the oneing that is in God. This

worshipful city that our Lord Jesus sits in, it

is our sensuality, in which he is enclosed, and

our natural substance is beclosed in Jesus

Christ, with the blessed soul of Christ, sitting

in rest in the Godhead. And I saw full surely

that it is needful

þat we ʃhall be in longynge

and in penance. into þe tyme

þat we be led ʃo depe in to god

þat we may

verely & truely

know oure

owne ʃoule. And

ʃothly I ʃaw

þat in to thys

high depenes

oure lorde hym

ʃelfe ledith

vs in þe ʃame loue

þat he made

vs. and in þe

ʃame

loue þat he

bought vs. bi his

mercy &

grace þrough vertue

of his

bleʃʃed paʃʃion. And

not withʃtondyng all

þis we

may neuer comme to the

full

knowyng of

god. tyll we firʃt

know clerely

oure owne ʃoule.

ffor into þe

tyme þat

it be in

the

that we shall be in longing and in penance, until the time that we be led so deep in to God that we may verily and truly know our own soul. And truly I saw that into the great deepeness our Lord himself leads us in the same love that he made us, and in the same love that he bought us, by his mercy and grace through virtue of his blessed Passion. And notwithstanding all this we may never come to the full knowing of God, until we first know clearly our own soul. For until the time that it be in the

ffull myghtis we

may not be

all full

holy. and þat is þat oure

ʃenʃualite.

by þe vertue of criʃtis

paʃʃion be

brought up into þe

ʃubʃtance with all the profitis of

oure

tribulacion þat

oure lorde

ʃhall make vs

to gete by mercy

& grace.

full strength we

may not be all fully holy. And that is that our

sensuality by the virtue of Christ∫€™s Passion

be brought up into the substance with all the

profits of our tribulation that our Lord shall

make us to get by mercy and grace.

Of interest, too, is that the Amherst Manuscript contains not only Julian's Showing of Love but also Jan van Ruusbroec's Sparkling Stone, translated into Middle English. Both Julian's Sixteenth Showing, P146, and the Sparkling Stone make use of Revelation 2.17. The Amherst Manuscript, A118, gives the text from Ruusbroec's Sparkling Stone discussing the Apocalypse of St John as the 'Book of the Secrets of God' addressed 'To him that overcometh', in which 'the ʃpirit ʃays in the Apocalyps vincenti ʃays he ʃchalle gyffe hym a lytil white ʃtone and in it a newe name the whiche no man knowes but he that takys it' . This is material Julian well could have shared with Margery.

Julian continues:

1st Gent. An ancient land in ancient oraclesJulian and Margery inscribe within the pages of their books their souls and their cities, black-clad Julian in her anchorhold in Norwich inscribing within that small space all the cosmos and its Creator while Margery in her white pilgrim robes trudges to Jerusalem and back.

Is called "law-thirsty:" all the struggle there

Was after order and a perfect rule.

Pray, where lie such lands now? . .

2nd Gent. Why, where they lay of old - in human souls.

Until Hope Emily Allen

identifed the Butler-Bowden manuscript in 1934 this was

all that was known of The Book of Margery Kempe. She next edited it for the

Early English Text Society, which has yet to edit the text

of Julian of Norwich.

Notes

1 CETEDOC CLCLT, Université de Louvain, CD

2 Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations, trans. Julia Bolton Holloway, pp. 113-119.

3

St Birgitta gives her Revelations to

Christendom

Revelationes, Ghotan:

Lũbeck, 1492

Sister

Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian

ever had. During the war years she was transcribing the

extant microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for

her Leeds University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent

editions by men based on her meticulous work failed to

credit her.

Sister

Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian

ever had. During the war years she was transcribing the

extant microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for

her Leeds University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent

editions by men based on her meticulous work failed to

credit her.

Indices to

Umiltà Website's Essays on Julian:

Preface

Influences

on Julian

Her

Self

Her

Contemporaries

Her

Manuscript Texts ♫ with recorded readings of them

About Her

Manuscript Texts

After

Julian, Her Editors

Julian in

our Day

Publications related to Julian:

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a page inside with

parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants

and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a page inside with

parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants

and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

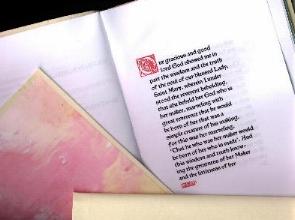

To see

inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's

in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

To see

inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's

in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2022

JULIA

BOLTON HOLLOWAY

||| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS

|| HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF

SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST

MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS,

BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||

http://www.umilta.net/soulcity.html

External Links:

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_61823_fs001r

http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/kempint.htm