And Hannah prayed and said 'My heart exults in the Lord, my horn is held high in the Lord . . . . '

'The Lord judges the ends of the earth, and gives strength to his king, and lifts up the horn of his anointed'. 1 Samuel 2.1, 10.'Truly I tell you, wherever this good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her'. Matthew 26.13; Mark 14.9

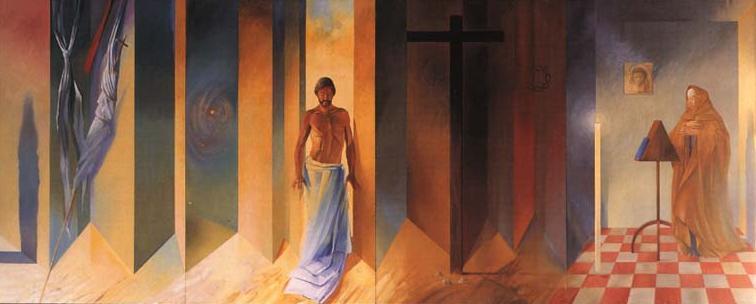

The illustration is taken from the painting of

Julian's 'Showings' in St Gabriel's Chapel, Community of All

Hallows, Ditchingham, Near Bungay, Suffolk. Painted by the

Australian artist, Alan Oldfield, it was earlier exhibited in

Norwich Cathedral. Photographed, Sister Pamela, C.A.H.

Reproduced by permission of the Community of All Hallows and

the Friends of Julian.

om Gregory Dix, O.S.B., studied the development of

the Christian sacraments, stating in The Shape of the

Liturgy and in The Theology of Confirmation in

Relation to Baptism that Christian liturgy preceded

the Gospels. For the Lambeth Greek Essay I had already

traced the simple Christian sacraments in contradistinction

to the costly Jewish sacrifices in Luke's Gospel, seeing

these as native to Mediterranean culture, John choosing free

water for baptism, Christ inexpensive wine for marriage and

daily bread for communion, but the multiplying Maries and

the other women who followed Christ purchasing costly olive

oil and rare spices for anointing. I now chose to study

anointing for the Gregory Dix Memorial Essay.

Then The Oil of Gladness came to hand.

Published in 1993, nearly fifty years later than Dom Gregory

Dix's 1946 University of Oxford Public Lecture on Confirmation

and Baptism, The Oil of Gladness also is a product of

the Anglo-Catholicism's 'Vision Glorious'. These texts look

back yet another fifty and hundred years toArthur

James Mason's 'The Relation of Confirmation to Baptism as

Taught in Holy Scripture and the Fathers' , published in

1893, again a work of Anglo-Catholicism. Anglo-Catholicism has

sought to heal the rift caused by the Reformation. This essay,

prompted by these works, will first trace unction and its

consequent 'Royal Priesthood' in the Hebrew Scriptures and the

Greek Testament as a liturgical continuum. It will also study

the association of anointing with women, first in Israel and

then in Christendom. Then it will observe the use of anointing

in the Church's liturgies of baptism and confirmation,

ordination and coronation, and of the sick and the dead. Last,

it will trace the vestiges of the 'Royal Priesthood' in the

Church of England, and suggest a revival of the Early Church's

sealing with chrism to be carried out in the great cathedrals

of our land by our bishops.

n Exodus 19.4-6, God had spoken magnificently to

Moses, saying, 'Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob, and

tell the Israelites: You have seen what I did to the

Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought you

to myself. Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep my

covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all

peoples, Indeed the whole earth is mine, but you shall be to

me a kingdom of priests [a royal priesthood], and a holy

nation'. In that passage God speaks of kings and priests in

one phrase.

n Exodus 19.4-6, God had spoken magnificently to

Moses, saying, 'Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob, and

tell the Israelites: You have seen what I did to the

Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought you

to myself. Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep my

covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all

peoples, Indeed the whole earth is mine, but you shall be to

me a kingdom of priests [a royal priesthood], and a holy

nation'. In that passage God speaks of kings and priests in

one phrase.

When we seek out the words for 'olive', 'oil', 'anoint' and 'horn' in a Strong's Exhaustive Concordance to the Bible we find that they occur in three contexts. The first is that of peace and fecundity, for example, the olive branch the dove carries back to Noah in Genesis 8.11, the land rich with wheat, vines and olive of Judges 15.5, and the children who stand about one's table like olive shoots in Psalm 128.3, all of which are 'zayith'. The fruit of that olive provided oil for lamps, for the cleansing and healing of skin, and for food; in the Mediterranean it functioned as does our beeswax and tallow for candles or electricity for lights, our soap to cleanse the skin and our butter for nourishment. The second context is that of anointing, first with consecrating priests and the furnishings of the Tabernacle of the Ark, 'mashach', that word being repeated also in the later context of the anointing of kings by priests, until the two are joined in Zechariah where the two anointed ones, Zerubbabel, Jesus' ancestor, and Joshua, Jesus' namesake, who are Priest and King rule together. From that word comes 'mashiyach', 'Messiah', the anointed one. The substance used for that anointing is the omnipresent olive oil, 'shemen', to which at times precious spices were added. It was used at God's command to anoint Aaron Israel's High Priest (Exodus 29, Psalm 133.2) and Samuel used it to anoint Saul and David, and Zadok to anoint Solomon as Israel's Kings (1 Samuel 10, 16, 1 Kings 1). An associated word is 'horn', the container for that oil, and idiomatically a way of saying that one is in a state of joy and prosperity, having an abundance of oil to pour upon oneself and others, 'qeren'.

Hannah exults over the birth of the miraculous and priestly child Samuel, speaking twice of the horn of oil, 'qeren', with which he will anoint first Saul (1 Samuel 10) and then David (1 Samuel 16). The first line in the Hebrew says 'And Hannah prayed and said ''My heart exults in the Lord, my horn is held high in the Lord'' '. The last line of her canticle, her psalm, echoes the first, saying that ' ''The Lord judges the ends of the earth, and gives strength to his king, and lifts up the horn of his anointed'' '. Hannah's song will be taken up in turn by Mary concerning the birth of her child, the Messiah, in the Magnificat (Luke 1.46-55), though it is in Zachariah's Benedictus (Luke 1.69) that the Greek reflects the Hebrew and gives again the image of the horn of the anointing 'And he raised up for us a horn, ['keras'] of salvation in the house of his servant David].

Samuel and David's Temple was the Tent of Meeting. Solomon then built the Temple of stone and cedar. Solomon married. Perhaps Psalm 45 with its lovely eighth verse, 'Therefore God, your God, has anointed you with the oil of gladness above your fellows', that oil mixed with myrrh, aloes and cassia, was written to celebrate that marriage. This psalm is in the same genre as is the Song of Solomon. And it is a genre which women composed, preparing one of their number for marriage. But its courtliness, its flattery, its elitism, counters Israel's true theology.

Israel was God's nation, his kingdom of priests, and all his people were his anointed ones, living in a theocracy. In Judaism and Christianity, there is a celebration of the 'world upside down', such as we see in Hannah's Song, in Mary's Magnificat, and in Christ's Beatitudes, where the poor and downtrodden shall be raised up from the dust and be worthy of a seat among princes (1 Samuel 2.8). In Judaism it is the mother who begins the Sabbath by blessing and lighting the lamps - now candles but once of olive oil - while the father blesses the wine and the bread - in that order - and it is the child who begins the Passover by asking a question, all of these celebrants being of the laity. Hence Mary could have dignity in Joseph's household in Nazareth and Jesus could question the doctors even in the Temple. So had Miriam (whose name is Mary), her mother, and Pharoah's daughter together saved the child Moses, allowing for the liberating Exodus from Egyptian bondage to occur and for Aaron's priestly caste to commence. So had David the shepherd boy become king. Victor Turner's anthropological studies have shown how the most powerful rituals, such as pilgrimage, interrupt hierarchies by their insistence upon liminal states in which all become equal, 'He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich empty away' (Luke 1.52-53).

That humbling of hierarchies occurs not only with

unction but also with blessing. Richard Hooker saw the Hebrew

form of blessing as continuing into Christian confirmation,

the imposition of hands as inherited from the act of blessing

conferred by Israel upon Ephraim and Manassah, Joseph's sons.

In the Hebrew Scriptures and in Jesus' Parable of the Prodigal

Son, the younger child is favoured over the elder, which

Christian exegetes would come to read as God's preference for

the Gentile as younger brother over the Jew as older brother.

Rembrandt movingly painted the scene of Jacob's Blessing with

the younger child raised above the older, hands crossed upon

his breast, head bowed in prayer, their most beautiful mother

the witness.

First John, then Jesus, sought to reform Israel back to being a priestly people that cared for the orphan and the widow. John made it possible for such cleansing to take place without blood sacrifices bought by money, but instead with the use of simple and free water, a cleansing accompanied by conversion, while he lived himself in the Wilderness in simplicity and poverty. Jesus added to John's use of water, wine and bread, available to any Mediterranean peasant. Mary (in Luke, an unnamed woman, who in the medieval tradition was thought to be Mary Magdalene), then came and added to these substances oil from the olive, mixed with precious spices.

When Christ came to be anointed by a woman at the house of Simon the Leper in Bethany, two days before the Last Supper, he chided the chiding disciples, among them Judas, saying that what she has done will be told in remembrance of her wherever theGospel is proclaimed in the whole world (Matthew 26.13; Mark 14.9; see also Luke 7.36-50, who had the event be earlier and in Galilee; John 12, who had it be six days before Passover). Jesus' words echo Psalm 44.8,18, which had described the anointing with the oil of gladness, then stated to the bride of the marriage, 'I will make your name to be remembered from one generation to another; therefore nations will praise you for ever and ever'. Jesus added, in three of the accounts, that this anointing by the woman was in preparation for his burial (Matthew 26.12; Mark 14.8; John 12.7).

In Judaism it was forbidden for a lay person to make or apply such chrism, which is olive oil mixed with myrrh and balm (Exodus 30.22-33). The tale of the anointing of Christ by a sinful woman occurs in all four Gospels, albeit with differences. That tale is followed by the 'idle' one (Luke 24.11) of the women, including Mary Magdalene, coming to the tomb with spices to anoint and embalm the corpse of Christ (Matthew 27.55-28.10, Mark 15.40-16.8 and shorter ending, Luke 23.55-24.11, John 20.1-2, 11-18), who thus become the first (though not legal), witnesses to the Resurrection. John, Jesus and whoever Mary was, whether the Magdalene or the sister of Martha and Lazarus or another, and the other women who followed Jesus from Galilee, supporting the disciples out of their resources (Luke 7.1-3), ministering to them, made it possible for all Israelites, women as well as men - and later all Gentiles - to be a priestly people consecrated to God.

Jesus' band, with John's before his, changed the

rules, reversing hierarchies into liminality, Jesus' band even

including women. John and Jesus together instituted a powerful

Messianic reform of Judaism back to its earliest theocratic

principles - which was resisted utterly by those who stood to

lose from that reform, those who had gained privileges, wealth

and power from the fear and corruption that conquest brings,

such men as the privileged Priests and Scribes, and even from

those normally opposed to them, the Pharisees, who, in this

instance, colluded with them in plotting to destroy their

critic and judge, Jesus.

In Zachariah's Benedictus or Blessing, Aaron's oil for the anointing of priests and the house of David come together splendidly in one verse, 'He has raised up for us a horn of salvation in the house of his servant David' (Luke 1.69), the priest with his words anointing the child, yet to be born, a king, as had Samuel anointed David, as is even England's Queen anointed at her Coronation. Zachariah adds that through this Saviour, the nation of Israel will be consecrated and righteous before God (Luke 1.75). When the angels told the shepherds of the birth of the child, they announced, 'that to you this day is born a saviour who is Anointed Lord, in the city of David' (Luke 2.11). When Zachariah's son, John the Baptist, heralded Christ as baptizing not with water but with the Holy Spirit and flame, he had just been asked if he were not himself the Christ, the Messiah, the Christ, the Anointed (Luke 3.15). Yet, though the Holy Spirit descended upon Christ, as had the Holy Spirit descended upon Mary his mother at the Annunciation, no physical anointing with oil occurred in the scene of baptism. Jesus next, filled with the Spirit, was driven into the Wilderness for the Temptation, returning to the Galilee region after forty days. Then, when Jesus read the passage from Isaiah in the Synagogue at Nazareth , he recited and applied to himself the words, 'The spirit of the Lord is upon me and he has anointed me to bring the Gospel to the poor' (Isaiah 61.1). His audience, his congregation in the Synagogue, would know that those verses go on to speak further of the oil of the anointing, of 'the oil of gladness instead of mourning' (Isaiah 61.3; Psalms 45, 133; Hebrews 1.9). This was Jesus' most overt 'kyrygma' in Luke, during his lifetime, announcing himself as Messiah. He immediately learned not to do so, barely escaping with his life from the enraged crowd at Nazareth.

Strangely, that anger was prompted by his preaching to them of Elijah being sent by God in time of drought not to his own people but to a Syro-Phoenician widow, a Gentile, who had only a jar of meal and a cruse of oil, and of another miracle, where Elisha healed the Syrian leper Naaman at the urging of the little Jewish slave handmaid. In the first miracle Elijah miraculously made the meal and oil continuously replenish themselves and, further, raised the widow's son from the dead (Luke 4.26; 1 Kings 17). Shortly before the second story, in that same scroll, Jesus' audience would remember, was the story of the widow of a prophet whose children were to be taken as slaves and who only had a jar of oil, which Elisha in turn had miraculously be kept replete, filling many other containers with which to pay her debts (2 Kings 4,5).

The reading of Isaiah 61.1, was a verbal proclamation, a speech act, concerning the Messianic anointing - which linked the similarly named Isaiah, 'Yeshaiah,' and Jesus, 'Yeshua'. Yet nowhere do we hear of the physical act of anointing, though often we hear of Jesus as called the Christ, the Anointed One, except in these two shadow stories concerning widows, one a Gentile, the other a Jew, and except in the story of the sinful woman who gate-crashed Simon the Pharisee's dinner party and who washed Christ's feet with her tears, dried them with her hair, and kept kissing them and anointing them from an alabaster jar of myrrh (Luke 7.38). Christ, then, turned to Simon and said among other things that he had not anointed his head with oil but that she was anointing his feet with myrrh (Luke 7.46). The oil for the anointing of priests and kings and guests and recovered lepers and the dead was concocted from olive oil mixed with myrrh and other precious spices. It is following this episode that we have Peter, another Simon, blurt out that Jesus is the Anointed of God (Luke 9.20). The Gospels collude in associating women with Christ's anointing.

On the way to Jerusalem while traveling on the border of Samaria with Galilee Jesus met a group of ten lepers. He told them they were to show themselves to the priest. One turned back on finding himself cleansed and healed and praising God, thanked Jesus, who asked where the other nine were. Jesus then told this one leper, who was a Samaritan, that his faith had healed him (Luke 17.11-19). Edersheim gave a careful account of the ritual for the cleansing of lepers-which concluded with the anointing with oil. In this instance, the tenth leper had not needed that Temple cleansing, his belief in the Christ being sufficient.

In Jerusalem, Jesus customarily spent his nights on the Mount of Olives , a 'Sabbath day's walk' from the Temple, to which he and his disciples went even following the 'Last' Supper (Luke 22.39). To cross from Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives they had to pass over the defiling, polluting tombs of the Jewish dead that lie everywhere in the ravine of Kidron, which were carefully white-washed to prevent such danger a month prior to Passover.

When next we hear of anointing it was again to be by women but this time it did not happen. The women who had followed him from Galilee at early dawn brought the spices they had prepared to anoint his body but it was gone from the tomb. Mary Magdalene and Joanna, Herod's steward's wife, and the others then told the disciples of finding the tomb empty and of the angels, the disciples considering these things but an idle tale, until Peter checked into the story himself (Luke 23.56-24.1-12,22-24).

In Hebrew, Jesus is spoken of as the Messiah, which in the Greek Gospels becomes 'Christos', both words meaning the 'Anointed One'. In the Gospels his anointing is not a priestly one by a male, but a lay anointing by a woman. While in the parable in the Gospel the anointing with oil and wine of the wounded traveler was effected neither by the priest nor the Levite but by the outsider, the almost Gentile, the Samaritan. Indeed there is a Messianic vocabulary in the Greek Testament, a clustering of words, of healing, of mercy, of coming, of freedom. And the word 'anointed', reflects as well, 'kind, loving, good, merciful'. Similarly, in Hebrew, there are echoes between the names of Joshua, 'Yehoshua,' and Jesus, 'Yeshua,' and the words for salvation, deliverance, help. Jesus Christ in his names, his words, and his deeds extended the franchise of holiness, of the royal priesthood, to all who believed on him, children, slaves, women, men, tax-collectors, lepers, paralytics, lunatics, beggars, the lame, the blind, the deaf, proclaiming, 'Whoever receives a child in my name, receives me, and whoever receives me receives the one who sent me' (Luke 9.48).

Jesus told women and men that their faith had saved

them. He did so in the double miracle (and double pollution)

of Jairus' twelve-year-old daughter raised from the dead and

the polluting woman who touched the fringe of his garment who

had been haemorrhaging for twelve years to whom Jesus said,

'Daughter, your faith has saved you; go in peace' (Luke 8.48).

He did so to the Samaritan leper. He did so to the thief on

the cross at his right hand. He implied again and again to

unclean and criminal lay women and men that they had returned,

through their faith and metanoia, as were also

children in their innocence, to being in his image who had

created them, that they were saved and healed, their sins

forgiven them, that they had entered the Kingdom of God. He

preached not a religion of Pharisaic separatedness, but one of

global inclusion.

he Epistle to the Hebrews, the Epistle of Barnabas

and the Gospel of Luke are related to each other. The Epistle

to the Hebrews was included in the scriptural canon; not so

Barnabas' Epistle. Both are, as it were, post-graduate texts,

post-catechetical texts, being essays in Comparative

Scripture, Religion and Liturgy: 'Let us bear on toward

perfection, not laying again the foundation . . . of teaching

about baptism, laying on of hands' (Hebrews 6.1-2). Cyril, as Archbishop

of Jerusalem, Jerusalem's Christian High Priest, paradoxically

made much use of the Epistle to the Hebrews in his Catechetical

Lectures. In the Gospel of Luke, in the Epistle to the

Hebrews, and in the Epistle of Barnabas there is the

demonstration, the argument, the thesis that the Levitical

priesthood, of Moses and Aaron, has somehow failed Israel, as

indeed had Aaron himself failed the Israelites with the

shaping of the Golden Calf in Exodus. (Peter, with his very

human fears [Luke 5.8], doubts [Matthew 14.22-33], and denial

[Luke 22.54-62], of Christ, reenacts Aaron's betrayal of Moses

[Exodus 32].)

he Epistle to the Hebrews, the Epistle of Barnabas

and the Gospel of Luke are related to each other. The Epistle

to the Hebrews was included in the scriptural canon; not so

Barnabas' Epistle. Both are, as it were, post-graduate texts,

post-catechetical texts, being essays in Comparative

Scripture, Religion and Liturgy: 'Let us bear on toward

perfection, not laying again the foundation . . . of teaching

about baptism, laying on of hands' (Hebrews 6.1-2). Cyril, as Archbishop

of Jerusalem, Jerusalem's Christian High Priest, paradoxically

made much use of the Epistle to the Hebrews in his Catechetical

Lectures. In the Gospel of Luke, in the Epistle to the

Hebrews, and in the Epistle of Barnabas there is the

demonstration, the argument, the thesis that the Levitical

priesthood, of Moses and Aaron, has somehow failed Israel, as

indeed had Aaron himself failed the Israelites with the

shaping of the Golden Calf in Exodus. (Peter, with his very

human fears [Luke 5.8], doubts [Matthew 14.22-33], and denial

[Luke 22.54-62], of Christ, reenacts Aaron's betrayal of Moses

[Exodus 32].)

The Epistle to the Hebrews (5.6,10, 6.20, 7.1-28) used Psalm 110.4,5's line, 'You are a priest for ever, after the order of Melchizedek', words vowed by God in the Psalm, allowing Hebrews 7.17 to stress instead the priesthood of the Gentile Priest King of Salem, Melchizedek, rather than the Jewish High Priest, Aaron, partly because its author cannot find that Jesus, from the house of Judah, had any priestly associations (Hebrews 7.13-14), but more importantly because this was a priesthood of simplicity and generosity, a mystical priesthood of the sacraments of water, wine, bread and oil, rather than of blood sacrifices, of heave and wave offerings, of sin and thank offerings, of the blood of bulls, of lambs, of goats, of birds, with scarlet wool and hyssop, today no longer carried out except by Samaritans and in Islam. It is as if the circle of Paul, if not Paul himself, with people such as Barnabas, Luke, and perhaps Apollos and Prisca, were helping shape Judaism into Christianity. This mystical priesthood of Melchizedek, in the realm of eternity rather than of time, and with the simplest sacraments, is of peaceable inclusion, rather than of rigorous exclusion.

Related to the Epistles to the Hebrews and of

Barnabas is also one written by Peter or an elder of Rome

echoing God's words to Moses, 1 Peter 2.9, 'But you are a

chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for

his possession, that you might proclaim his redemptive acts',

which it embeds in the words from Isaiah Jesus spoke

concerning the stone the builders rejected but which became

the head of the cornerstone of the new Temple (Isaiah 8.14-15,

Luke 20.17). The concept is echoed also in Revelation 5.10,

'You have made them a kingdom and priests to God and they will

rule on earth.' Israel had been conquered by Rome, but simple

fishermen like Peter and Andrew, tax collectors like Matthew

Levi (is he a tax collector for Rome or for Jerusalem, for

Caesar or for the Temple?), even Pharisaic tent-makers, like

Paul, Prisca and Aquila, came to conquer their conquerors and

under Helena and Constantine the

Roman Empire adopted for its official state religion,

Judaeo-Christianity, the religion of the oppressed, of women

and slaves.

he Gospels gave the four sacraments of water, bread,

wine and oil. The first, of water, was begun by John. Jesus

administered those of bread and wine. But it was a woman who

administered the oil of the anointing, along with the water of

her tears, in true metanoia. Her footwashing of the

Messiah at a supper was then humbly imitated by him in his

similar ministry to the disciples at the Last Supper.

he Gospels gave the four sacraments of water, bread,

wine and oil. The first, of water, was begun by John. Jesus

administered those of bread and wine. But it was a woman who

administered the oil of the anointing, along with the water of

her tears, in true metanoia. Her footwashing of the

Messiah at a supper was then humbly imitated by him in his

similar ministry to the disciples at the Last Supper.

In Christianity, Christians, women and men, follow Christ, becoming in his image, first with the cleansing from sin through baptism by water, then with the consecration into holiness through the anointing with oil, next to be sustained with the bread and wine of the Eucharist. The sacrament that once made Christians most truly 'Christian' in the early Church was decidedly that carried out with the oil of the anointing.

Gregory Dix's The Shape of the Liturgy

traced the Early Church's continuation of these Gospel

concepts, derived from Jewish liturgical practices, until the

centrality of the Bishop, representing the anointed Christ

with the power to anoint all Christians, and served by Deacons

for men, Deaconesses for women, in this task, became lost with

the introduction of Priests taking over most of the Bishop's

and Deacons' and Deaconesses' roles. (In so doing Christianity

perhaps became again Levitical and Pharisaic.) Gerald Vann in

The Divine Pity cited St Ambrose, 'We are all anointed

into one holy priesthood', and discussed at length the common

priesthood of the laity in which we all share. The High Priest

Jesus inaugurated the possibility that all humankind could be

of the Royal Priesthood, in his image, who created us and who

atoned, or, as Julian of Norwich would say, 'at oned ', for us, 'noughting our sins.

Patristic texts used typology, blending the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures. Tertullian noted of anointing, 'After we come up from the washing and are anointed with the blessed unction, following that ancient practice by which, ever since Aaron was anointed by Moses, there was a custom of anointing them for priesthood with oil out of a horn. That is why [the high priest] is called a christ, from "[chrism"] which is "[anointing"]: and from this also our Lord obtained his title'. Tertullian continued by speaking of the baptismal waters as like the Flood and the oil as like the olive branch in the dove's mouth. The Didascalia Apostolorum discussed the bishop's sealing of the baptismal candidate with the words 'You are my son: this day I have begotten you' (Psalm 2.7, Hebrews 1.5,9, 2.11-12,17, 5.5).

St Cyril of Jerusalem in his catechetical lectures told the candidates that the anointing of exorcism made them 'partakers of the good olive tree, Jesus Christ', and that they are anointed and 'properly called Christs, and of you God said ''Touch not my Christs'' (Psalm 105.15)', adding that with the anointing with chrism they are now 'Christians'. Sermons preached by St John Chrysostom, discovered in 1955, also spoke of the anointing 'for through the chrism the cross is stamped upon you'. These texts wrote, as in the Syrian 'Narsai', of the oil as a visible symbol of the Holy Spirit and of its strengthening and healing powers. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and James of Edessa similarly discussed the use of the oil of anointing in baptism.

Ambrose, who baptized Augustine, wrote of the anointing as from Psalm 133 and I Peter 2.9, of the ointment upon the head that ran down Aaron's beard, and of the chosen generation as priestly and precious. Augustine, too, described baptism as followed by anointing. He spoke of that anointing as the consecrating to the 'royal priesthood'-'just as we call all "[Christians"] by reason of the mystical chrism, so we call all "[priests,"] because they are members of the one Priest', the one Christ. He also stated, 'The anointing belongs to all Christians . . . and we all, in Him, are both christs and Christ' and 'Christ means anointed; He is called Christ from the chrism: - in Hebrew, Messias, in Greek, Christ ; in Latin, Anointed'.

The Councils also provide information concerning anointing. The First Council of Toledo, A.D. 398, decreed that the bishop shall bless the chrism and send it into his diocese by means of deacons and sub-deacons from each church before Easter. (Bishop Eric Kemp so blesses the chrism annually for the clergy of the Diocese of Chichester.) Leo spoke of the blessing of the chrism as taking place on Maundy Thursday. The First Council of Orange's Canon 2, 441, legislated that chrismation with chrism should only occur once, either at baptism, or, if omitted then, at confirmation. A letter from Pope Innocent to Decentius, 446, stated that consignation with chrism should only be carried out by bishops, not priests, citing the Acts of the Apostles which told how Peter and John were directed to deliver the Holy Spirit to Samaritans already baptized by Philip. Priests could anoint the head with the chrism but only the bishop could mark the cross upon the brow in sign of the Holy Spirit.

These Fathers and Councils described adult baptism. Confirmation was to become separated from baptism where infant baptism became the norm. Travelling through time, let us look at the later forms, for infants, first in the 'Ambrosian Manual' from Milan which, though tenth century, likely still reflected aspects of Augustine's baptism at the hands of Bishop Ambrose. It spoke of the chrism as poured into the font crosswise, then the baptism in the mixed water and oil, followed by the sign of the cross made on the infant's head with chrism. We read of this in Bede and Cuthbert. The Stowe Missal from Ireland stated the same. Likewise did the Sarum Rite. Then in Rome from John the Deacon and in Charlemagne's Empire under Alcuin of York, we learn of the use also of a chrism cloth of white linen placed on the head of the initiates as emblem of their royal priesthood.

At the Reformation, which took place in the north of

Europe where the olive does not grow, the use of oil was

dropped. In relation to this agronomy the Sarum Missal had

already introduced the use of candles in baptism which the

Alternative Service Book now, anachronistically, restores. The

Protestant Church of England only retained unction for the

anointing of the monarch. However, of the XXXIX Articles,

Article XXVII gave a trace of the earlier anointing, reading

in part 'our adoption to be the sons of God by the Holy Ghost

are visibly signed and sealed'. The ASB has restored the

anointing with oil or chrism in its rubrics for baptism and

confirmation but as an option.

t is clear that the Early Church was filled with

women in positions of responsibility and respect. Luke began

with Elizabeth as a daughter of Aaron (1.5), and with Anna the

prophetess (2.36), the Greek aspirating her name as 'Hannah',

relating her to Samuel's mother. The Acts of the Apostles told

us of the Apostles at prayer, 'together with certain women,

including Mary, the mother of Jesus' (1.14), while it was

likely under the roof of John Mark's mother, named Mary, that

the Last Supper and Pentecost took place (12.12). Acts 9.36

gave us Dorcas a disciple, Acts 21.9, Philip's four virgin

daughters who were prophets. Where Westcott and Dix argued for

the precedence of Epistle over Gospel that argument should

also prove the presence of women in the Early Church, with

Romans 16 acknowledging Phoebe, a deacon, Prisca, Mary, Junia

(unless he is Junias), an apostle, Tryphaena, Tryphosa,

Persis, Rufus' mother, Julia, and Nereus' sister, and with

Galatians 3.28 proclaiming 'As many of you as were baptized

into Christ have clothed yourself with Christ. There is no

longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there

is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ

Jesus'. Dix, in A Detection of Aumbries, describes

Early Christians, in that spirit, laity as well as clergy,

women as well as men, carrying about with them the reserved

sacrament for use by the ill and the dying as well as the

whole and well.

t is clear that the Early Church was filled with

women in positions of responsibility and respect. Luke began

with Elizabeth as a daughter of Aaron (1.5), and with Anna the

prophetess (2.36), the Greek aspirating her name as 'Hannah',

relating her to Samuel's mother. The Acts of the Apostles told

us of the Apostles at prayer, 'together with certain women,

including Mary, the mother of Jesus' (1.14), while it was

likely under the roof of John Mark's mother, named Mary, that

the Last Supper and Pentecost took place (12.12). Acts 9.36

gave us Dorcas a disciple, Acts 21.9, Philip's four virgin

daughters who were prophets. Where Westcott and Dix argued for

the precedence of Epistle over Gospel that argument should

also prove the presence of women in the Early Church, with

Romans 16 acknowledging Phoebe, a deacon, Prisca, Mary, Junia

(unless he is Junias), an apostle, Tryphaena, Tryphosa,

Persis, Rufus' mother, Julia, and Nereus' sister, and with

Galatians 3.28 proclaiming 'As many of you as were baptized

into Christ have clothed yourself with Christ. There is no

longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there

is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ

Jesus'. Dix, in A Detection of Aumbries, describes

Early Christians, in that spirit, laity as well as clergy,

women as well as men, carrying about with them the reserved

sacrament for use by the ill and the dying as well as the

whole and well.

In Hebrew and Greek cultures, though less so in Roman, a rigorous separation of gender was maintained, women and men worshipping in different parts of the synagogue and Temple. Therefore deaconesses were involved in the more intimate actions of the baptisms of women candidates, while deacons oversaw that of men. The Didascalia Apostolorum gave a careful account of these customs, while noting that for men and for women this was done 'as of old the priests and kings were anointed in Israel'. The Apostolic Constitutions noted that women deaconesses anoint women candidates 'for there is no necessity that the women shall be seen by men', but that 'in the laying on of hands the bishop shall anoint her head only as the priests and kings were formerly anointed . . . from Christ the Anointed, "[a royal priesthood and an holy nation"]'.

The Testamentum Domini showed how widows and deaconesses stood with the bishop, priests, deacons and readers at that altar. The same text gave the Offices widows and virgins, God's 'handmaidens', prayed at midnight and at dawn. The world's oldest codex is a fourth-century Psalter found in the grave of a twelve-year-old girl in a pauper cemetery near Cairo. The late fifth century Statuta Ecclesiae Antiqua's Canon 12 said 'Let widows and nuns who are chosen for ministering to female candidates for baptism be so instructed in their duty that they may be able in clear and sensible language to teach the uneducated and rustic women at the time of their preparation for baptism how they are to reply to the questions of him that baptizes them, and in what manner they are to live when they have been baptized.'

The ordination of these deaconesses spoke openly of their role as mirroring that of the prophetesses of the Hebrew Scriptures, for instance in the Apostolic Constitutions: 'Concerning a deaconess . . . O bishop, you shall lay your hands upon her, in the presence of the presbytery. and of the deacons and the deaconesses, and say: O eternal God, Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the creator of man and of woman, who filled with the Spirit Miriam, and Deborah, and Hannah, and Hulda; who did not disdain that your only-begotten Son should be born of a woman; who also in the tent of witnesses and in the temple appointed women to be keepers of your holy gates; do you yourself now look upon this your servant, presented for the office of a deacon, and give her your Holy Spirit . . .' That text continues that virgins and widows were not ordained but simply admitted into the Orders of Virgins and Widows. It was from these Orders in the Early Church that nuns and their convents had their origin. Nuns historically preceded monks. Abelard, who knew the Lives of the Desert Fathers, including the Letters of Jerome to holy women, explained to Heloise that she, as an abbess, was a deaconess.

The paradox is that, despite the importance of women

in the Early Church, there is a liturgical forgetting of

Christ's statement that the woman's anointing of him shall be

remembered wherever the Gospel is preached

in the whole earth (Matthew 26.13; Mark 14.9).

When William Sawtre, Margery Kempe' s chaplain at St Margaret's, Lynn, was condemned as a lapsed heretic on February 24, 1399, he was first fully garbed as a priest, then his chalice and paten and priestly raiment taken from him, next his Gospel as deacon, down to his candle-lighter as acolyte, and finally his keys as doorkeeper being removed from him, at which point he had become again a lay person and could be led forth to be burned at the stake. A pope is also a bishop; a bishop, a priest; a priest, a deacon. Until recently, a priest even wore the maniple of the deacon, the towel of the servant, on his arm. Cyril of Jerusalem wrote movingly of how 'King Jesus, when about to be our Physician, having girded himself with the napkin of human nature, ministered to what was sick'. Christians are likewise servants, the Pope the 'servant of the servants of God'.

In none of these explications of ecclesiastical hierarchies is anointing mentioned. However, Arthur Mason, in a footnote, explains 'that the use of unction in Ordination is modern (not earlier than the ninth century), local (unknown in the East) and partial (an unction of the hands only). That of which unction is the symbol was held to have been given once for all,' that is, to all baptized Christians as of the Royal Priesthood. The Early Church's anointing with chrism made all believers priestly. Today, however, Roman Catholic priests are anointed with the oil of the catechumens, Roman Catholic bishops consecrated with chrism.

Unlike Christendom's theocratic Royal Priesthood, the very word 'monarch' signifies 'one ruler'. Ancient Mesopotamia had anointed kings and priestesses. The Hebrew Scriptures spoke of the anointing of priests, prophets and kings and those words embed themselves in the liturgies for Christian anointing. Jeffrey John notes that the Holy Spirit 'anointed' Jesus at the Jordan the Messianic King, echoing with 'This is my beloved Son', the words of the Coronation Psalm 2, 'You are my Son, today I have begotten you.' Gerhart Ladner in The Idea of Reform studied Byzantine theocracy, where the Emperor was the 'Logomimesis', the 'Imitation of the Word', and Ernst Kantorowicz showed how even the imperial and now Christian coinage came to be stamped with the head of Christ rather than Caesar. Kantorowicz' The King's Two Bodies discussed how medieval and Tudor England - and Shakespeare - saw King and Realm as mirroring each other, each having obligations to the other. Then Kantorowicz demonstrated that system's breakdown with the Stuart adoption of the unilateral Byzantine 'Divine Right of Kings', upsetting a delicate constitutional balance and prompting Civil War and Regicide.

Despite these political changes, our Christian

monarchs of England, whether Roman or Anglican, are anointed

with oil and with chrism at their coronations. L. G. Wickham

Legg and Geoffrey Rowell have movingly discussed this national

heritage. To their discussion let us add Handel's music,

'Zadok the Priest,' its words taken from the prayer for the

consecration of the oil, its reference being to the anointing

of Solomon, Israel's wise monarch and Temple architect. Today

our anointed Head of the Church of England is the Queen.

A Roman Catholic child is baptized with salt, olive oil, water and chrism. An Anglo-Catholic child was, until quite recently, baptized just with water and words. Perhaps at Confirmation the Bishop may now sign the candidates' foreheads with the cross in chrism. Kings, Queens, Priests and Deacons are now anointed, but for the Anglican laity, until recently, there was only, and rarely at that, Extreme Unction at approaching death. Today, though there is a return to more use of the oil of anointing, we have largely lost this major Gospel sacrament in the Church of England specifically and in Protestantism generally. Partly this is because in northern Europe the olive cannot be made to grow. But today's technology, transportation and marketing once again makes it possible for those who read the Bible's pages to use also the products of which it speaks, the fruit of the Mediterranean earth and the work of Mediterranean hands. Once it was olive oil mixed with spices sealed upon the brow by the Bishop which made us 'Christian', meaning 'anointed', as does the epithet 'Christ' which we use of Jesus. It can be so again.

The 'Vision Glorious' is that we are in Christ's

image, we are, as Julian said, 'even-Cristens', equally

Christians, in God's eternity, rather than in time and space's

unfair hierarchies. Therefore Christ's anointing, by the Holy

Spirit and by Mary Magdalene and the other women, is also

ours. Jesus' 'Gospel' is that Israel's Holy Spirit cannot be

destroyed by Rome, but will convert the whole world to God,

who is 'Abba', ' Our Father '. Perhaps, in this 'Decade

of Evangelism', of this 'Good News', we could contemplate

reforming the Reformation's Church of England to be again

truly 'Christian'. Perhaps our anointed Queen as the Head of

our Church of England, with the Head Rabbi, with Cardinal

Hume, with the Archbishop of Canterbury, could inaugurate this

unction, this blessing, at her Maundy Thursday Service at Westminster Abbey , bestowing it

ecumenically upon her people. Perhaps such an anointing could

permit Anglo-Catholics to receive at Roman Catholic

Eucharists. Perhaps the Church of England could, throughout

our land, resurrect this nearly 'Lost' Sacrament, calling upon

all to become truly 'Christened' at an Order of Anointing (as

in Orders of Baptism, of Matrimony) in our Cathedrals,

restoring to these beautiful structures their liturgical

reason for being, the Order being presided over by our

Bishops, assisted by Deacons and Deaconesses, as in early

Christianity, at the same time that we give thanks to the

Peoples of the Book for what we have inherited with them, and

so become a holy people, a people reconsecrated to God.

Arthur James MasonBibliography

The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Trans.

Betty Radice. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

Adai and Mari. The Liturgies

of the Holy Apostles Adai and Mari together with the

Liturgies of Mar Theodorus and Mar Nestorius and the Order

of Baptism. Ed. Mar Thoma Darmo Metropolitan. Trichur,

South India: Mar Nasai Press, 1967.

Alter, Robert and Frank Kermode,

editors. The Literary Guide to the Bible. London:

Fontana, 1987.

The Liturgical Portions of

the Apostolic Constitutions: A Text for Students.

Trans., ed., annotated and introduced, W. Jardine Grisbrooke.

Bramcote: Grove Press, 1990. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical

Study 13-14.

Aprem, Mar. ‘The Chaldean Syrian

Church in Trichur: A Study of the History, Faith and Worship

of the Chaldean Syrian Church in Syria since A.D. 1814 to the

Present Day’, D.Th. Dissertation, United Theological College,

Bangelore, 1974.

Asch, Sholem. The Nazarene.

Trans. from Yiddish, Maurice Samuel. London: George Routledge,

1939.

Athanasius, Palladius, Jerome

and Others. The Paradise or Garden of the Fathers Being

Histories of the Anchorites, Recluses, Monks, Coenobites and

Ascetic Fathers of the Deserts of Egypt. Trans. A.

Wallis Budge. London: Chatto and Windus, 1907. 2 vols.

The Authorised Daily Prayer

Book of the United Hebrew Congregaton of the British Empire.

London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1912.

Baldovin, John F., S.J. Liturgy

in Ancient Jerusalem. Bramcote: Grove Books, 1989.

Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 9.

Balmforth, Henry. The Royal

Priesthood. London: The Church Union, 1956.

Barnabas. ‘The Epistle of St

Barnabas’. The Apostolic Fathers: The Epistles of Saints

Clement of Rome and Barnabas and ‘The Shepherd of Hermas.’

London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh, n.d. Apostolic

Fathers, Part I, Ancient and Modern Library of Theological

Literature.

Barthes, Roland. ‘La lutte avec

l’ange: Analyse textuelle de Genèse 32.23-33.’ Analyse

Structurale et exégèse biblique. Ed. François Bovon.

Neuchâtel: Delachaux et Niestlé, 1971. Pp. 26-39.

Bavidge, Nigel. A Child for

You: Baptism. Leigh-on-Sea: Kevin Mayhew, 1978.

Beckwith, Roger. Daily and

Weekly Worship: Jewish and Christian. Bramcote:

Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study, 1987. Grove Liturgical Study 49.

Bevan, Edwyn. Jerusalem

under the High Priests. London: Edward Arnold, 1904.

Bibles: Hebrew Scriptures.

Vienna: Holzhausen, 1874. The Greek New Testament, ed.

Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger,

Allen Wikgren. Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, 1983. The

New Oxford Annotated Bible, New Revised Standard Version,

ed. Bruce M. Metzger, Roland E. Murphy. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1989.

Birth and Belonging: A

Handbook on Baptism. Westminster: Church Information

Office Publishing, 1977.

Bradshaw, Paul F., ed. Essays

in Early Eastern Initiation. Bramcote: Grove Press,

1988. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 8.

Bushnell, Katherine C. God’s

Word to Women. North Collins, New York: Ray Munson,

1923.

Catholic Dictionary.

1917.

Chrysostom. On the

Priesthood. Trans. T. Allen Moxon. London: SPCK, 1907.

Clarke, W. K. Lowther and

Harris, Charles, eds. Liturgy and Worship: A Companion to

the Prayer Books of the Anglican Communion. London:

SPCK, 1964.

Clay, Rotha Mary. The

Hermits and Anchorites of England. London: Methuen,

1914.

Confirmed in Love: The Holy

Spirit and the Sacrament of Confirmation. Brentwood: St

Paul Publications, 1969, 1975.

Cooper, Henry. Holy Unction:

A Practical Guide to its Administration. Banstead:

Chrism, 1966.

Crisis for Confirmation.

Ed. Michael Perry. London: SCM Press, 1967.

Cullmann, Oscar. Baptism in

the New Testament. Trans. J.K.S. Reid. London: SCM

Press, 1950.

Cyril, Archbishop of Jerusalem.

Catechetical Lectures. London: Walter Smith, 1885. A

Library of Fathers of the Holy Catholic Church Anterior to the

Division of the East and West, Translated by Members of the

English Church.

____________________. Lectures

on the Christian Sacraments: The Protocatechesis and the

Five Mystagogical Catecheses. Ed. Frank Leslie Cross.

London: SPCK, 1951.

Daniélou, Jean. The Presence

of God. Trans. Le Signe du Temple, Walter Roberts.

London: Mowbray, 1958.

The Desert Fathers.

Trans. Helen Waddell. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,

1957.

Dix, Dom Gregory, O.S.B. A

Detection of Aumbries With Other Notes on the History of

Reservation. Westminster: Dacre Press, 1942.

________________. God’s Way

with Man: Addresses for the Three Hours. Foreword, the

Bishop of Durham. Westminster: Dacre Press, 1954.

________________. The Image

and Likeness of God. Westminster: Dacre Press, 1953.

________________. The

Question of Anglican Orders: Letters to a Layman.

Westminster: Dacres Press, 1944.

________________. The Shape

of the Liturgy. Westminster: Dacre Press, 1945.

________________. The

Theology of Confirmation in Relation to Baptism: A Public

Lecture in the University of Oxford delivered on January

22nd 1946. Westminster: Dacre Press, 1946.

Dodd, C.H. According to the

Scriptures: The Sub-Structure of New Testament Theology.

London: Collina, 1965.

_____________. The Parables

of the Kingdom. London: Collins, 1961.

Dudley, Martin and Rowell,

Geoffrey. The Oil of Gladness: Anointing in the Christian

Tradition. London: SPCK, 1993.

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping

of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Dugmore, C. W. The Influence

of the Synagogue upon the Divine Office. Westminster:

Faith Press, 1964. Alcuin Club 45.

Edersheim, Alfred. The

Temple: Its Ministry and Services as They Were at the Time

of Jesus Christ. London: Religious Tract Society, 1874.

Empereur, James. Models of

Liturgical Theology. Bramcote: Grove Press, 1987.

Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 4.

Eusebius. Ecclesiastical

History. Trans. Kirsopp Lake, J.E.L. Oulton. Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980. 2 vols. Loeb Classics,

153, 265.

Gray, George Buchanan. Sacrifice

in the Old Testament: Its Theory and Practice. Oxford:

Clarendon, 1925.

Grelot, P. and J. Pierron. The

Pascal Feast in the Bible. Baltimore: Helicon, 1966.

Gusmer, Charles W. The

Ministry of Healing in the Church of England: An

Ecumenical-Liturgical Study.Great Wakering:

Mayhew-McCrimmon, 1974. Alcuin Club 56.

Hobart, William Kirk. The

Medical Language of St Luke. Dublin: Dublin University

Press Series, 1882.

Holloway, Julia Bolton. ‘Dante’s

Commedia: Egyptian Spoils, Roman Jubilee, Florence’s

Patron’. Studies in Medieval Culture 12 (1978),

97-104.

Hooker, Richard. Of the

Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie, Eight Books. London:

William Stansby, Matthew Lownes, 1617.

Hoskyns, Sir Edwin and Noel

Davey. The Riddle of the New Testament. London: Faber

and Faber, 1958.

The Hospital Chaplain.

Birmingham: Birmingham Regional Hospital Board, 1967.

Ignatius and Polycarp. The

Epistles of St Ignatius and St Polycarp. London:

Griffith Farran, n.d. The Apostolic Fathers. Vol. II.

Jagger, Peter. Clouded

Witness: Initiation in the Church of England in the

Mid-Victorian Period, 1850-1875. Allison Park,

Pennsylvania: Pickwick Publications, 1982.

Jerome. ‘Hieronymvs ad Fabiolam

de vestitu sacerdotum’. Opus Epistolarum diui Hieronymi

Stridonensis, una cum scholiis Des. Erasmi Roterodami.

Parisiis: Guillard, 1546. Vol III. 18v-21v.

John Paul II. Apostolic Letter,

‘Mulieris dignitatem,’ On the Dignity of and Vocation of

Women. Vatican City: St Peter’s, 1988.

Josephus. The Jewish War.

Trans. G. A. Williamson. Harmondworth: Penguin, 1959, 1970.

Kantorowicz, Ernst. The

King’s Two Bodies A Study of Medieval Kingship.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Kenyon, Frederic G. Our Bible

and the Ancient Manuscripts. London: Eyre and

Spottiswoode, n.d.

______________. Handbook to

the Textual Criticism of the New Testament. London:

Macmillan, 1901.

Kimhi, David. The Longer

Commentary of R. David Kimhi on the First Book of Psalms

London, Trans. R.G. Finch, Introduction, G.H. Box. SPCK, 1919.

Klauser, Theodor. A Short

History of the Western Liturgy: An Account and Some

Reflections. Trans. John Halliburton. London: Oxford

University Press, 1969.

Küng, Hans. Christianity:

The Religious Situation of Our Time. Trans. John Bowden.

London: SCM Press, 1995.

__________. Judaism: The

Religious Situation of Our Time. Trans. John Bowden.

London: SCM Press, 1992.

Ladner, Gerhart B. The Idea

of Reform: Its Impact on Christian Thought and Action in the

Age of the Fathers. New York: Harper, 1967.

Lampe, G.W.H. The Seal of

the Spirit: A Study in the Doctrine of Baptism and

Confirmation in the New Testament and the Fathers.

London: SPCK, 1967.

Lignée, Hubert, C.M. The

Living Temple. Baltimore; Helicon, 1966.

Magonet, Jonathan. A Rabbi

Reads the Psalms. London: SCM, 1994.

Manson, T.W. The Servant

Messiah: A Study of the Public Ministry of Jesus

Cambridge: University Press, 1961.

Martin, M. M. I Was Sick and

Ye Visited Me: A Manual on the Church’s Ministry to the Sick.

Westminster: Faith Press, 1958.

Mason, Agnes, C.H.F. ‘The

Healing of the Gadarene Demoniac: Notes of an Mason, Agnes,

C.H.F. ‘The Healing of the Gadarene Demoniac: Notes of an Idiotae

on the Gospel Stories.’ Offprint from Theology

(September, 1935).

Mason, Arthur James. The

Relation of Confirmation to Baptism as Taught in Holy

Scriptures and the Fathers. London: Longmans, Green,

1893.

Merton, Thomas. The Sign of

Jonas. London: Hollis and Carter, 1953.

Metzger, Bruce M. Manuscripts

of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

_____________. The Text of

the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and

Restoration. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Morris, Joan. Against Nature

and God: The History of Women with the Jurisdiction of

Bishops. London: Mowbrays, 1973.

Morton, H.V. In the Steps of

the Master. London: Rich, 1934

_____________. In the Steps

of St Paul. London: Rich, 1936.

Moule, C.F.D. The Origin of

Christology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1977.

Oesterly, W.O.E. A History

of Israel. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932, 1948. 2 vols.

Palmer, G.H. The Order of

Tenebrae. Wantage: St Mary’s Convent, 1929.

Pseudo-Dionysius. The

Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibhead and Paul Rorem.

Preface, Rene Roques. Introductions, Jaroslav Pelikan, Jean

LeClercq, Karlfried Froelich. London: SPCK, 1987.

_______________. In Migne, J.P.

Patrologiae cursus completus: Series Graeca. Paris,

1889. Vol. 3.

Ratcliffe, Edward Craddock.

Liturgical Studies. Ed. A. H. Couratin and D. H. Tripp.

London: SPCK, 1976.

Rembrandt and the Bible:

Stories from the Old and New Testament, Illustrated by

Rembrandt in Paintings, Etchings and Drawings. Ed.

Hidde Hoekstra. Utrecht: Magna Books, 1990.

Ricci, Carla. Mary Magdalene

and Many Others: Women Who Followed Jesus. Trans. Paul

Burns. London: Burns and Oates,1994.

The Origins of the Roman

Rite. Ed. and Trans. Gordon P. Jeanes. Bramcote: Grove

Press, 1991. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 20.

Rowell, Geoffrey. The Vision

Glorious: Themes and Personalities of the Catholic Revival

in Anglicanism. Oxford: Clarendon, 1983.

Russell, D.S. The Jews from

Alexander to Herod. London: Oxford University Press,

1967.

[Seeley, Sir John.] Ecce

Homo: A Survey of the Life and Work of Jesus Christ.

London: Macmillan, 1866.

Shimun, Surma d’Bait Mar. Assyrian

Church Customs. London: Faith Press, 1920.

Some Authentic Acts of the

Early Martyrs. Trans. and ed. E. C.E. Owen. Oxford:

Clarendon, 1927.

Streeter, Burnett Hillman. The

Four Gospels: A Study of Origins Treating of the Manuscript

Traditon, Sources, Authorship and Dates. London:

Macmillan, 1926.

Talley, Thomas, J. ed. A

Kingdom of Priests: Liturgical Formation of the People of

God: Papers Read at the International Anglican Liturgical

Consultation, Brixen, North Italy, 24-25 August 1987.

Bramcote: Grove Books, 1988. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 5.

The Testamentum Domini: A

Text for Students, with Introduction, Translation, and

Notes. Ed. Grant Sperry-White. Bramcote: Grove Books,

1991. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 19.

Thomas. The Gospel According

to Thomas. Ed. Guillaumont, A, H.-Ch.Puech, G. Quispel,

W. Till and Yassah ‘Abd al Masih. Leiden: Brill and London:

Collins, 1959.

Tischendorf, C. Codex

Sinaiticus: The Ancient Biblical Manuscript now in the

British Museum. London: Lutterworth, 1934.

Tolstoy, Leo. Christ’s

Christianity. Trans. H.F. Battersby. London: Kegan Paul,

Trench, 1885.

Turner, Victor. Revelation

and Divination in Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell

University Press, 1975.

______________. The Ritual

Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine,

1968; Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

______________ and Edith Turner.

Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. New York:

Columbia University Press, 1978.

Union of Superiors General. Consecrated

Life Today: Charism in the Church for the World.

International congress, Rome 22-27 November 1993.

Middlegreen: St Pauls, 1994.

Vann, Gerald, O.P. The

Divine Pity: A Study in the Social Implications of the

Beatitudes. London: Sheed and Ward, 1946.

Vermes, Geza. The Dead Sea

Scrolls in English. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

_____________. Jesus the

Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels London:

Collins, 1973.

Westcott, Brooke Foss. The

Epistle to the Hebrews: The Greek Text with Notes and

Essays. London: Macmillan, 1903.

_____________. A General

Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament.

London: Macmillan, 1870.

_____________. An

Introduction to the Study of the Gospels. London:

Macmillan, 1872.

Whitaker, E. C. Documents of

the Baptismal Liturgy. London: SPCK, 1960, 1970.

Wilkes, David. Concilia

Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, Quattuor Voluminibus

Comprehensa. London, 1737.

Williams, C.F. Abdy. Handel.

London: J.N. Dent, 1901.

Wilson, Michael. The Church

is Healing. London: SCM Press, 1966.

Witvliet, Theo. A Place in

the Sun: And Introduction to Liberation Theology in the

Third World. London: SCM Press, 1985.

The Wonder of Divine Healing:

A Divine Healing Symposium. Ed. A. A. Jones. The Drift,

Evesham: Arthur James, 1958.

Wyman, F. L. Commission to

Heal. London: SPCK, 1954.

Zerwick, Max and Mary Grosvenor.

Grammatical Analysis of the Greek New Testament. Rome:

Biblical Institute Press, 1974.

I wrote this essay as an Anglican Novice in the Community of the Holy Family now twenty five years ago. Since then I have fled to Italy, become anointed Catholic by Don Divo Barsotti, at Candelmas, 1998, then Consecrated, at Epiphany, 1998, then repeating the Vows of Poverty, Chastity and Obedience, at Pentecost, 1999, again at the Assumption 2006, Vows I had already made to God as Anglican, 15 August 1996. There are ways, needing to be further opened up, for the Laity to be Consecrated, deepening our Baptismal Promises, our Christenings, as monasticism lived in the world.

Meanwhile,

I have changed from advocating anointing, finding this also can

be abused, to the simple blessing and giving of Gethsemane olive leaves themselves. We have now

sent these blessed olive leaves to Nairobi, Omagh, Goteborg,

Istanbul and to many individuals for trauma healing.

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |