Marie d'Oignies|| Angela of Foligno || Umilta of Faenza

Birgitta of Sweden || Catherine of Siena || Julian of Norwich

Margery Kempe ||

Chiara Gambacorta || Francesca Romana

St Birgitta giving her Revelations to Christendom.

Birgitta, Revelationes,

Ghotan: Lübeck, 1492.

he Rhineland Mystics, Meister

Eckhart , Henry Suso , John Tauler and Jan van Ruusbroec were part of an

important, and usually Dominican, network, encouraging and

influencing each others' contemplative writings and sermons.

What is not generally realised is that there is yet another

circle of mystics, women this time, on the medieval European

Internet, that stretched even farther afield, from

Scandinavia, England, Italy and even reaching Bethlehem and

Jerusalem. This circle included a Swedish noblewoman, widowed

mother of eight children, a Norwich anchoress, a Sienese

dyer's daughter, a Lynn merchant's wife who bore fourteen

children, a Pisan ruler's widowed daughter and a Roman wife

and mother of three children. They are Marie

d'Oignies , Angela of Foligno ,

Umilta of Faenza , Birgitta of Sweden , Catherine of Siena , Julian of Norwich , Margery Kempe , Chiara Gambacorta and Francesca Romana .

he Rhineland Mystics, Meister

Eckhart , Henry Suso , John Tauler and Jan van Ruusbroec were part of an

important, and usually Dominican, network, encouraging and

influencing each others' contemplative writings and sermons.

What is not generally realised is that there is yet another

circle of mystics, women this time, on the medieval European

Internet, that stretched even farther afield, from

Scandinavia, England, Italy and even reaching Bethlehem and

Jerusalem. This circle included a Swedish noblewoman, widowed

mother of eight children, a Norwich anchoress, a Sienese

dyer's daughter, a Lynn merchant's wife who bore fourteen

children, a Pisan ruler's widowed daughter and a Roman wife

and mother of three children. They are Marie

d'Oignies , Angela of Foligno ,

Umilta of Faenza , Birgitta of Sweden , Catherine of Siena , Julian of Norwich , Margery Kempe , Chiara Gambacorta and Francesca Romana .

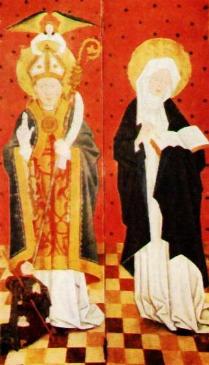

Bishop Hemming and St Birgitta, Diptych, Finland

This is what she wrote in a vision about and to King Magnus. In it she sees a lectern and a book. 'For the appearance of the lectern was as if it had been a sunbeam [of red, gold, white]. . . . And when I looked upwards, I might not comprehend the length and breadth of the lectern; and looking downward, I might not see nor comprehend the greatness nor the deepness of it . . . After this I see a Book on the same lectern, shining like most bright gold. Which Book, and its Scripture, was not written with ink, but each word in the book was alive and spoke itself, as if a man should say, do this or that, and soon it was done with speaking of the Word. No man read the Scripture of that Book, but whatever that Scripture contained, all was seen on the lectern. Before this lectern I see a king . . . The said king sat crowned as if it had been a vessel of glass closed about . . .'

She continues to describe how the king's glass globe is protected by an angel but threatened by a demon . . . 'This living king appears to you as if in as it were a vessel of glass, for his life is but as it were frail glass and suddenly to be ended'. She continues by speaking of how this king knowingly sins but that if he repents he can be saved by the angel from the fiend. Beside him is a dead king above whom is writing describing his lust, his pride, his avarice. . . but the writing is blankly gone from the part that should have proclaimed his love of God.

'Then the Word speaks from the lectern, saying "[What you see is the Godhead's self. That you cannot understand the length, breadth, depth and height of the lectern means that in God is not found either beginning or end. For God is and was without beginning, and shall be without end "]. Also the Word spoke to me and said "[The Book that you see on the lectern means that in the Godhead is endless justice and wisdom, to which nothing may be added or lessened. And this is the Book of Life, that is not written as the world's writing, that is and was not, but the scripture of this Book is forever. For in the Godhead is endless being and understanding of all things, present, past and to come, without any variation or changing. And nothing is invisible to it, for it sees all things "]. That the Word spoke itself means that God is the endless Word, from whom are all words, and in whom things have life and being. And this same Word spoke then visibly when the Word was made man and was conversant among men'. She adds to the King that she is giving him the Word's words, adding that 'few receive and believe the heavenly words given from God, which is not God's fault, but man's'.

Later, she writes 'I saw an altar and a chalice with wine and water and bread and I saw how in a church of the world a priest began the mass, arrayed in a priest's vestments. And when he had done all that belonged to the Mass, I saw as if the sun and moon and the stars with all the other planets, and all the heavens with their courses and moving spheres, sounded with the sweetest note and with sundry voices.'

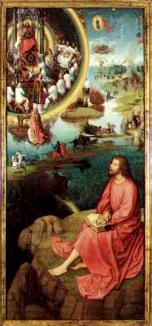

St John writing the Apocalypse, Hans Memling, St John's Hospital, Bruges

In another vision, at the end of her life, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, she sees the judgement of her wicked son Charles where her prayers and her tears for Charles cause the devil to have amnesia concerning her son's sins. First the book in which the fiend has written them down suddenly has blank pages instead of writing, then the sack in which he has placed them is empty when turned inside out, then the devil himself forgets them totally from his memory and goes wailing off to Hell, cursing Birgitta.

Much of Birgitta's visionary imagery comes from law courts, for her father was the King of Sweden's law man and her husband was likewise a law man. She both prophesied and wrote following the Black Death of 1348 when Doomsday, Judgment Day, seemed particularly near. She told King Magnus that the Black Death would happen, then left for Italy, Sweden being too dangerous for her. Birgitta set up her household in Rome, living in prayer and constantly receiving visions, having male secretaries assist her, one of them a Spanish Bishop, Alfonso of Jaén. In the last year of her life she journeyed to the Holy Land, preaching on her journey in Naples and Cyprus, prophesying the 1452 Fall of Constantinople. Her massive book of the Revelationes, which is really Julian's title of 'Showings', was copied out in illuminated manuscripts, then in print, and treasured throughout Europe.

At her death Alfonso of Jaén, Queen Joanna of

Naples, Queen Margaret of Sweden, the Emperor Charles of

Bohemia, and Cardinal Adam

Easton of England, a Benedictine from Julian's Norwich,

all sought Birgitta's canonization as a saint.

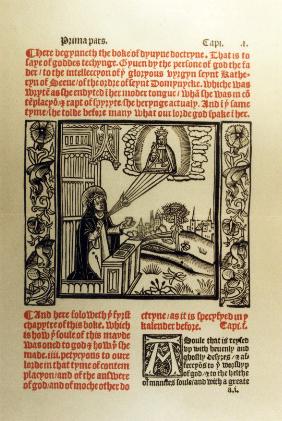

Catherine of Siena, The Orcherd of Syon (Dialogo) , London: Wynken de Worde, 1519

ope Gregory XI sent Alfonso of Jaén to Catherine of Siena at

Birgitta of Sweden's death. At that point Catherine, who had

previously been illiterate, proceeded to write important

letters to Popes and Emperors, Kings and Queens and even to

the condottiere Sir John Hawkwood, on the need for peace. We

do not think of her as part of the Dominican-inspired

Friends of God movement across Europe but this act clearly

places her in that context. Pope Urban VI wanted her to have

Birgitta's daughter, Catherine of Sweden, accompany her to

carry out diplomacy on his behalf with Queen Joanna of

Naples.

ope Gregory XI sent Alfonso of Jaén to Catherine of Siena at

Birgitta of Sweden's death. At that point Catherine, who had

previously been illiterate, proceeded to write important

letters to Popes and Emperors, Kings and Queens and even to

the condottiere Sir John Hawkwood, on the need for peace. We

do not think of her as part of the Dominican-inspired

Friends of God movement across Europe but this act clearly

places her in that context. Pope Urban VI wanted her to have

Birgitta's daughter, Catherine of Sweden, accompany her to

carry out diplomacy on his behalf with Queen Joanna of

Naples.

Catherine had been the twenty-fourth child of a Sienese dyer. Everyone had wanted her to marry but she refused, having made a vow of chastity, and instead sought to enter the Dominican Third Order, which only admitted women who were widows. She won. As a Dominican Tertiary she cared for the sick and dying, including criminals condemned to death in Siena. She was surrounded by disciples, one of them an English hermit, William Flete, whose work, The Remedies Against Temptations, Julian quotes and uses in the Showings, another a lawyer Cristofano Di Ganno, who later translated Birgitta's Revelations into exquisite Italian, another a painter, Andrea Vanni, whose delicate portrait of her survives, indeed in the very place of her major visions in San Domenico, Siena.

Andrea Vanni, St Catherine of Siena, San Domenico, Siena

Her confessor and biographer was Raymond of Capua who became head of the Dominican Order. Pope Urban VI leaned heavily upon her for his own survival. Severely anorexic, she died at the age of thirty-three, collapsing under the weight, she said, of the Church.

Besides her Letters she had also written, or, again, rather dictated, the Dialogo, the Dialogue between God and his Daughter, Catherine's Soul, in which he tells her that his Son is the bridge between God and man, a bridge that is like a stair, beginning first with the affections, then love, then peace. He adds that his Son's 'divinity is kneaded with the clay of your humanity like one bread'. This work, likely through Cardinal Adam Easton of Norwich who knew all three women, influenced Julian's Showings, her 'Revelations'. A most beautiful manuscript of the Dialogo was translated into Middle English for the Brigittine nuns of Syon Abbey and called the Orcherd of Syon. It was printed by Wynken de Worde, Caxton's successor, again with that title, in 1519. It is illustrated above. Its exemplar may well have been a manuscript Adam gave Julian.

ulian, Anchoress of St Julian's Church in Norwich,

is not normally thought to have been influenced by Birgitta of

Sweden and by Catherine of Siena, yet it is clear that her Showingsgets its concept and

its title from Birgitta's influential work while much in its

text resonates with that in Catherine of Siena's Dialogo. It is clear, too, that,

just at St Birgitta spends her a lifetime writing her Revelationes,

so does Julian spend a lifetime writing her Showings. It is

also clear, once the life of Adam

Easton, Norwich Benedictine, is known, that that

influence largely came from him. He avidly defended St

Birgitta's canonization, arguing for women and their

theological abilities, citing among other examples the four

daughters of Philip who were each prophetesses and who helped

Luke write his Gospel and Book of Acts. Adam would also have

exposed Julian to the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius

, for he owned his complete works in a manuscript that

survives today at Cambridge University, and he may indeed have

written for her the Dionysian 'Cloud of Unknowing '

and its related 'Dionise Hid Diuinite' and Epistles. Julian

thus may have had a spiritual director, Adam Easton, who

taught Hebrew at Oxford, just as Birgitta had Master Mathias

who studied Hebrew at Paris. Julian's St Julian's Church was

also next door to the Austin Friary, a Friary in contact with

the Austin Hermit William Flete, Catherine

of Siena' s disciple and executor.

ulian, Anchoress of St Julian's Church in Norwich,

is not normally thought to have been influenced by Birgitta of

Sweden and by Catherine of Siena, yet it is clear that her Showingsgets its concept and

its title from Birgitta's influential work while much in its

text resonates with that in Catherine of Siena's Dialogo. It is clear, too, that,

just at St Birgitta spends her a lifetime writing her Revelationes,

so does Julian spend a lifetime writing her Showings. It is

also clear, once the life of Adam

Easton, Norwich Benedictine, is known, that that

influence largely came from him. He avidly defended St

Birgitta's canonization, arguing for women and their

theological abilities, citing among other examples the four

daughters of Philip who were each prophetesses and who helped

Luke write his Gospel and Book of Acts. Adam would also have

exposed Julian to the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius

, for he owned his complete works in a manuscript that

survives today at Cambridge University, and he may indeed have

written for her the Dionysian 'Cloud of Unknowing '

and its related 'Dionise Hid Diuinite' and Epistles. Julian

thus may have had a spiritual director, Adam Easton, who

taught Hebrew at Oxford, just as Birgitta had Master Mathias

who studied Hebrew at Paris. Julian's St Julian's Church was

also next door to the Austin Friary, a Friary in contact with

the Austin Hermit William Flete, Catherine

of Siena' s disciple and executor.

Julian's manuscripts, like those of Catherine of

Siena, are copied out again and again in the context of Syon Abbey , the Abbey

deliberately founded in England in accordance with St

Birgitta's Rule by Henry V, in response to her desire for

peace between England and the rest of the world.

Interestingly, both Julian (circa 1413) and Syon Abbey (1434)

were visited by an indefatigable woman pilgrim, mother of

fourteen, Margery Kempe.

Hear http://www.umilta.net/soulcity.mp3

for the conversation between Julian and Margery.

These women, who left all to follow Christ in their love of God and their neighbour in God's image, were linked to each other across the map of Europe and did much for the status of women and the state of the Church. When one reads their canonization documents witnessing their miracles it is to find that the miracles centre on the powerless, on women and on children, on the condemned and the oppressed, on servants and nuns, and that these may well respond with seemingly miraculous healing because their saviour is a member of their own oppressed half of society. What is also characteristic of this network is that it is as it were a 'literacy campaign', in which women, barred from universities and education, are the writers of Sybilline books of prophecy which are more powerful even than those written by men. They are writing, Cardinal Ratzinger has said, 'revealed theology'. Saint Catherine of Siena, socially the least in this group, we do not forget, has been proclaimed by the Church a 'Doctor of the Church', the equal of the learned Saints Jerome and Gregory. Let us call them very practical mystics.

Indices to Umiltà Website's Julian Essays:

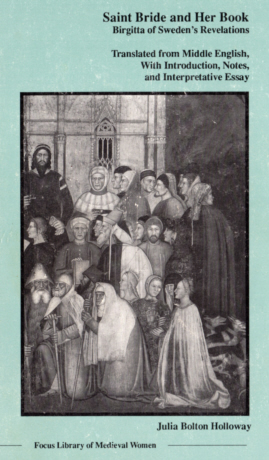

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

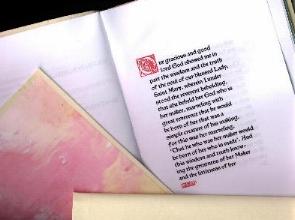

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

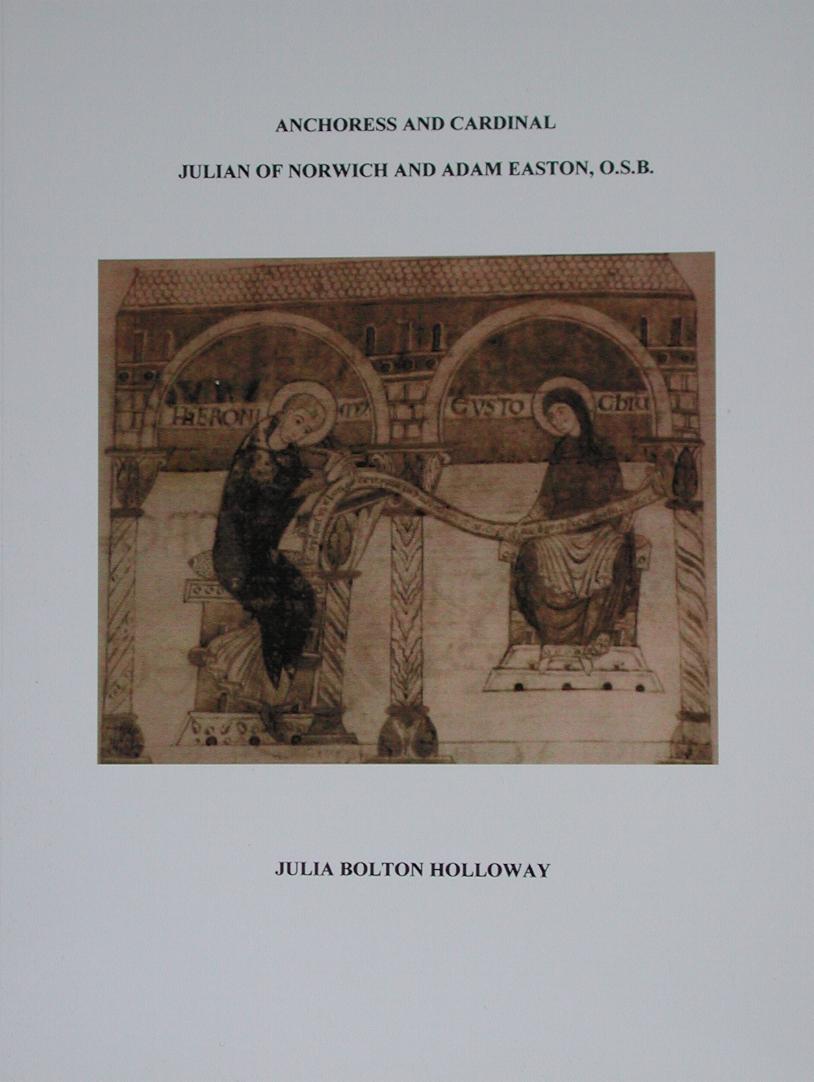

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2022 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||