Rose and trunk

We were all used to scrubbing floors, polishing and cleaning and black-leading grates. In the last year we were taught basic cookery and spent one day a week in the laundry, learning how to wash, starch and iron - with heavy flat irons, which were heated on a red-hot stove in the ironing room. Yes, I'd learned a lot, and I knew it all. I was sixteen years old, and looked forward to going out in the world. What a shock I had in store. It hadn't occurred to me that one day I might be on my own. In the Institution I had my friends. We had learned, worked and played together for over thirteen years. Soon, I'd have no one.

"You're very lucky, Rose. You have been chosen." Everything moved very quickly. I was taken to a clothing store in town and fitted out with two of everything. These clothes were put into a tin trunk. How I got to this place of work, I do not remember. The Assistant Matron had brought me, and in saying "Goodbye," reminded me yet again how lucky I was to have been chosen. Then she was gone, and I was alone. I hadn't felt so alone since my mother had left me at the Institution all those many years before. But this time I didn't cry. I went to my bedroom. It was in the attic. In the room was a bed, a wooden chair and a table with a basin and water jug, a rail to hang my clothes on and in the corner my tin trunk. I remember looking out of the window and seeing buses and cars going by, and a newsboy on the corner calling out to buy his papers. So much noise. This was indeed a new world!

*

The lady called. She wanted me to change into my working dress to start right away. I quickly did her bidding. She told me what was expected of me. I was to rise at half past five in the morning and most days I would not be finished before eleven at night. I'd have half a day off weekly and Sunday evening to go to church. She would pay me five shillings a week. Up to now, apart from the dollar my brother sent me for Christmas, I had never had that much money all at once and I thought it was a fortune. I was really going to work hard for this in return. I soon found out just how hard I must work to earn it.

*

I was sixteen years old when I was given that tin trunk and a change of clothing and sent to a family in Blackheath as a domestic servant for five shillings a week. I worked daily from five in the morning until eleven at night with one half-day off a week, and two hours off on Sunday evening to go to Church.

*

That first night in service I thought I was going to die of loneliness and my early days in service I found a nightmare. I had to work to the clock. The routine went something like this:

Cleaning the grate

Rise at five thirty, clean the kitchen boiler and fire grate in the sitting room and all coal fire grates throughout the house, clearing away the ashes and relaying the fires. Furniture and ornaments had to be dusted. I'm afraid I broke some of the ornaments in my haste, so after a while I was not allowed to touch them. The breakfast table was to be laid, the hall tidied, front steps and brass on front door cleaned, all the shoes were to be cleaned. I cooked breakfast, then made myself presentable to serve it. After breakfast, made the beds, cleaned the bedrooms, landing and stairs, emptying chamberpots. Then at this time a weekly job was done, Monday washing, Tuesday ironing, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday spring cleaning each room. Next I would prepare and serve a light mid-day lunch. Afternoons were spent cleaning silver and makings scones and cakes for tea. These were always made fresh each day. This was followed by cooking a large evening meal, with endless pots and pans to wash. After which, wood, coke and coal had to be brought up from the cellar for the boiler and fires for the next day. Then I went to bed if the Mistress did not want me anymore.

"You will call me Madam and my husband the Master. You will not speak unless spoken to." (I was used to that.) "You will always stand if you are sitting when we enter the room. Knock on the door before you enter and never open the door if you are not told to do so. You will wear your cap and apron at all times."

Scrubbing the steps

After I had been in service a week, I seemed to have worked non-stop with no time for food, although none was really left for me. I ate left-overs if there were any. One midday I was so hungry I ate a whole small loaf of bread, nothing on it, just bread. At tea time the lady rang her bell to tell me she was having a visitor to tea and would I serve some bread and butter. "Where's the bread?" I asked. "There's a small loaf in the larder," she answered. "Oh, I ate that," I said. "I was hungry." "All of it?" she asked; her face showed signs of disbelief. However, it seemed to make her realize I had to eat and from then onwards she would leave some food for me.

*

Every Monday I did the big weekly wash. Sheets, table cloths, towels and personal clothing. The sheets and linen I boiled in a copper, heated with a wood fire. I did the rest of the washing by hand. I used soda and Sunlight yellow soap and a blue bag to whiten the sheets. Which at first turned out more blue than white. I used a large wooden mangle. I would hang the wash in the garden whatever the weather. In winter, the washing would freeze and hang like boards on the line. I expect I didn't mangle enough water out, but the mangle was large and hard to turn. My hands were red, and chapped with the wind and soda and the broken chilblains that covered them and my feet.

Rose and mangle, wringing the laundry

*

You may ask why I did not leave, but where would I go? As the time went by, the hours of drudgery, physical and social isolation, long hours of work, over a hundred each week, I got to wondering how long I would last. I had nowhere to go, I was alone, so like thousands of other orphans all over the country, in the same position as I was, I learned to keep my voice low and respectful and never to reply without a "Sir" or "Madam," never to talk, unless it would be to deliver a message or ask a necessary question, and then do it in as few words as possible. If I asked Madam a question and she was with anyone else, she would just ignore me. If I ever had to carry a case or parcel for the mistress, when she was going anywhere, I had to walk behind her. She would never be seen walking with a servant. The rule was accept your station in life without complaint!

*

When I had been in service about six weeks, the mistress' baby was born. I had been woken up at four o'clock, and told to make some tea. The Master went for the doctor. The Mistress sat on the stairs crying with pain. I just didn't know what to do to help, I was so frightened, as I didn't know what was happening. But then the doctor arrived and soon the baby was born. Then I really knew why the Mistress needed a servant. Baby clothes and nappies made a daily wash necessary, and to tend the baby's needs were added to my other duties. I remember clearly one evening after the baby was born, Madam went out to a party. I was left to look after the baby. At ten o'clock in the night I went and laid on my bed to wait for their return, and fell asleep. The next thing I heard was this woman shouting at me for being asleep. I jumped up and my foot gave way, my toe joint coming out of its socket. Not knowing what I had done, it was never seen to. The bone joint is out to this day, as later was too late to set it right.

The mistress would bath her baby in front of a gas fire in the nursery. I remember one day I heard a cry. I went rushing into the room to see what had happened. The baby had a six-inch long burn on its bottom. The Mistress had sat the little girl on her potty too near the fire. I rushed for the doctor, but the baby was in so much pain it couldn't stop crying and the burn was so deep she would be scarred for life.

The doctor left soft coverings and bandages, and I had another job. Four times a day I would stop what I was doing and dress the baby's wound. Even on my half-day off, if I'd gone out, I'd come back to dress it. This went on for many weeks. I grew very fond of the child. I'd say, "Hello, little someone," and Little Someone she became. I found myself doing more and more for her. She would laugh and smile everytime I went near her and cry when I left the room.

*

When it was my half-day off I would leave the evening meal all ready to put on the table, so there was no work for the Mistress to do. When I returned, I'd have to clear the table and wash up. Sometimes I'd show how cross I was about this situation by banging the pots and pans and making a lot of noise with the dishes. But it didn't do any good. Sometimes I got the comment of, "Do you feel better this morning?" I hadn't the nerve to tell her I wasn't going to wash up on my half-day off.

I can remember losing my temper many times. Madam would always ring a little hand bell when she wanted me. One day I was very busy. The Mistress had rung her little bell all day for this, or that. I'd got behind with my work, so I was late making the scones for tea. I had my hands in the flour, when the bell rang. I quickly washed my hands, and made myself presentable. I went and knocked on the door. She kept me waiting, then I heard, "Come." I went in. "Ah, Rose," she said, "Put a piece of coal on the fire." I just couldn't control myself. "Couldn't you even do that?" "Rose, how dare you . . . ." But I was gone with a slam of the door.

*

Everything always had to be perfect. I remember one time, there was a luncheon party. As well as my other duties I had to cook a four-course meal for ten people. I tried so hard but I remember that as I was serving the meal I dripped some gravy onto the table cloth. The Mistress was furious. She shouted at me to take everything away and change the cloth. But I burst into tears and ran from the room. I went to my room and cried and cried. I just couldn't take any more. Was so tired, I fell asleep. I woke about half past nine in the evening and went down stairs. I was so worried, I felt sure I would be given notice. I went into the kitchen to get something to eat. Madam was in there. She didn't say a word. I opened a tin of sardines and made a sandwich. I shared the rest with the cat. The Mistress said, "Your cat never does what it is told!" "It's not always easy," I said softly. She looked at me and burst out laughing. "Let's forget it," she said.

*

My first Christmas was a great come-down to what I had been used to at the Institution. There we would wake on Christmas morning to the sound of Carols. The boys would walk round the cottages with their band singing and playing. In our stockings we would find an orange and six boiled sweets. Paper-chains were hanging on the walls and we had fried bacon for breakfast. After Church, we had roast beef and Christmas pudding for lunch. We'd play musical chairs after lunch, and then we'd have tea with some of the boys. My first Christmas in service was a cold foggy day, the Master and Mistress were going out for the day, so I was left to look after the baby. Before she went out the Mistress gave me a present, a little working apron, as she said I needed a new one, and I was very down-hearted, and after they had gone out I had a good cry. Then I felt better. We went out and spent most of the day in Greenwich Park.

*

I remember a nice light moment that gave me great joy. (Young girls today would not believe it.) I was sent out on a message in my cap and apron, and I was hurrying along the road when a lorry-load of young workmen drove by and started cheering and whistling at me. I turned and they waved at me, and I waved back. They never knew what joy and uplift they gave me. I felt so good that someone had even noticed me.

*

It was unheard of to be ill in anyway, and if I had a cold or flu, the Mistress would say, "Go to bed when you have finished your work," or "Stay in bed on your half-day off." Which I did many times anyway, because I was so tired or because I had no money to spend.

I remember one time I worked for three weeks covered with spots, and nothing was said until one morning the Mistress said, "Oh, your spots have gone. You must feel better."

*

I was allowed to go to the evening service at church on a Sunday evening, but not allowed to sit where I wanted to. The churchwarden would be at the door, to show people to their seats. Grand ladies and gentlemen would be shown to the front rows of the church with great ceremony and smiles, and they would point to the back rows for such as myself. I would also be one of those who didn't get a handshake and smile from the priest on the way out, just a nod of the head, and he never once asked my name or where I worked. It was of no importance to him. I could not have given him the money he needed to keep his church going.

But for me prayers and faith are more important and that's just what I had. They couldn't take that away. Jesus and I worked together. When sometimes I found I couldn't go on, or everything was on top of me, it was because I hadn't talked to him about my days' work for fear of not getting all the work finished in time. I would start work the moment I got out of bed, but I learned after a time to pause and lift my eyes to heaven and pray for help, and as the day passed I would talk to Jesus all the time. I knew many hymns and would hum them all the time. No pop music, radio or television was to be had in my world of work.

*

When I had been in my first job for eighteen months I was given notice. The excuse was that I was getting too fond of the baby. I looked around for another place of work. This was not as easy as it sounds. By the end of the week I had to have at least a roof over my head, having no relatives or any one to turn to who would take me in for a while. The hunt was on. This time I had to find myself a job, and inwardly I felt a bit of panic. Where was I to start? The Mistress gave me two hours off in the afternoon to look for a job. In the Post Office I found out where there was a servants' registry office. I could put my name down for a day's pay. When I told the lady who ran the agency my wage was five shillings a week, she asked for one shilling, and said I should do better for wages in my next job as my face fell when she asked for a shilling. She had nothing on her books at the moment but perhaps she might if I called the next day. Asking for time off to find a job was a great worry, for all the work had to be fitted in somehow. Then at the end of the week the unbelievable happened. I was promised a job at twelve shillings and six pence a week. Then the lady I was working for changed her mind, and said she would like me to stay and would raise my wage to ten shillings weekly. I told her it now wasn't possible as my future employer was coming to see her that afternoon for my references.

*

I had been in service about three years, when a lady called to see me. She said she was an Inspector from the Institution, to see how I was getting on. I was so taken aback, I said, "What, after all this time?" "Yes," she said, "there are so many of you, I have only just been able to get around to you." I wondered, after she had gone, what awful misery most of us put up with, without anyone knowing anything about it.

*

About a month after the visit of the Inspector of the Institution something very exciting happened. I received a letter from her which said because I had stayed over a year in the service job the Home had found me I had been chosen to meet the Duchess of York at the Guild Hall in London (with, of course, many other orphans from other Homes in the country). There was a meeting point for us all to meet. This was very early in the day. That would mean I would have to ask for a whole day off. This was unheard of for a half day a week only was allowed.

This meant I had to ask Madam for extra time. It took me a long time to pluck up enough courage to ask her and when I did she said, "What do you want the whole day off for?" "I am going to visit the Duchess of York." She looked at me as if I had gone raving mad.

So I showed her the letter. I am sure she wasn't believing what she read. She said, "You can take a friend with you if you want to. Who are you asking to go with you." I said, "No one, I have no one to ask. I'll go on my own." Then she said, "You can have the day off." After that she kept coming in and out of the kitchen as if she wanted to say something. Then around ten o'clock when I was just bringing up the coke from the cellar to top up the boiler for the night she rang the bell. I quickly washed my hands, took off my apron and went to see what she wanted. I knocked on the door. She said, "Come in." And right away, she said, "Rose, I have been thinking. It will be much better if I go to the Guild Hall with you, when you see the Duchess of York." I couldn't believe it. I said, "Oh no, if you did you would have to stay in the gallery and any way it's only for servant girls." She said, "Don't worry. Nobody will mind." Under my breath I thought, "I will."

Anyway the next worry I had to think about was what would I wear. Everything I had was very worn and thin and all the brushing and cleaning wouldn't make it fit to see the Duchess in. I had no money to spend even if I had thought of buying something new.

Then I had an idea. Why not wear my Girl Guide uniform. At least it was the best I had. It wasn't worn that much and I kept it lovely and clean and I felt good in it.

Of course I was the only one in Guide uniform. That didn't worry me. So when the great day came, there was I, an orphan servant girl shaking hands with the Duchess of York (later to become Queen of England and now Queen Mum).

I was so excited, I didn't take in one word she said. She gave us all a photo of herself. I kept it for many years. Moving around in the war years I mislaid it. That was very sad. Anyway the Duchess of York had shaken my hand and I think she must have said with her wonderful smile, "Well done." And that was much more than any of the grand ladies I had worked for had done.

*

In 1934, my brother George came over to England. He was sitting in the kitchen where I worked when I returned from my half-day off. The surprise was too much for me and I started to cry. He was tired after his journey, but no hospitality of any kind was shown by my employers. He'd have slept on the floor if allowed, but he was directed to a guest house, about a mile away. He returned the next day wearing a large hat and a light coloured suit. I let him in and he walked straight into the lounge and sat down.

He was redirected to the kitchen, and I was given a lecture that he could come and see me as long as he knew his place. I could give him a lettuce sandwich and a cup of tea. After three days he told me he didn't like "rabbit food" and I could give him a lump of the gingerbread I had made the day before.

He told the lady I worked for that I worked very hard, and that she was very lucky to have me. I still remember the look on the lady's face. I can laugh now, but at the time I was doing my best to get my brother away from the lady as quickly as possible.

George took me out quite a bit on my afternoons off. One day, we went to the Zoo. He had a camera and took some pictures. I still have them. George didn't stay very long in England. For a while I didn't know where he was. Then about four months later, I had a letter. He was back in Canada, and I was alone again.

*

In the middle Thirties, I had gained better confidence in myself and knew I was able to do most jobs well. By this time I had joined the Girl Guides and the Young Women's Christian Association, and met some folk of my own age, one afternoon and one evening a week, plus a prayer meeting on Sunday after church.

One of the friends I made was working in service not far from me, and she hated it. One day she told me she had heard there were two rooms being rented out for seven shillings and sixpence a week. It sounded a fortune to me. She asked me if I would leave my live-in job and get a daily job and share her rented rooms. Nothing like this had occurred to me before and I got quite excited about it, but my excitement grew less as everyone I came in contact with were against the idea, telling me of the pitfalls of leaving the sheltered life of domestic service. Looking back, I can see their point, but at the time I wouldn't listen. I was going to do what I wanted to do. You know, you can't tell anything to the younger generation!

After much thought and planning, I started looking around for a daily job. I knew I would have to stand out for more money - at least a pound a week. I was under one month's notice. On my afternoon off, I would do my rounds of the domestic agencies. Here again, I met opposition. Did I know what I was doing, and what expenses I would incur? They could offer me some wonderful live-in jobs. I could take my pick. No, thank you. I wanted a daily job. Well, that wouldn't be easy. Please call again. I called many times. Then one day I was offered a job from seven in the morning to seven at night, at a pound a week, starting the next Tuesday. I was delighted as that was the day after leaving my live-in job, and whatever was right or wrong with this job, I knew I would have to take it.

*

I remember so well leaving my last live-in job. I was due to leave at twelve noon, I did all my work in the morning and prepared lunch. I was so excited, I couldn't get away quickly enough. The lady said to stay and have some lunch, but I was in too much of a hurry. The lady gave me my wages and two parcels. In one was an eiderdown for my bed. This was from the Mistress, who said if I'd stayed with her for seven years, and not six, she would have given me two blankets. The other parcel was a lovely leather writing case, from the Grandma of the children. I was so taken aback, such generosity had never been shown before. After my goodbyes, I went out the back door with a new wooden trunk and my two parcels and I was as free as a bird. I spent a whole shilling in a Lyons Tea Shop for a meal of sausages and beans. I don't think anything has ever tasted so good.

*

We didn't have much in our two rooms - two beds, a table and two chairs, and there was a sink and a gas ring to boil a kettle on. We made do on what we were given to eat at work as we couldn't afford to buy extra food. We were free to go our own ways. At first I got very tired and went to bed early. It was so nice to be able to go to bed if I wanted to and not be on call to midnight.

My new job meant paying two pence on the bus to get to work early in the morning. I would walk home to save the fare. Then I found my shoes needed mending more often. The lady took to me right away. She hadn't had a daily help for a long while and I think she took me on as a gift from heaven. She had four children and her husband was a school master. I told her where I had worked before, but she didn't seem interested, and didn't get a reference. There was a different atmosphere working in a daily job. I didn't have to depend on feeling owned. I went to work fresh every morning and was treated as someone who mattered, someone to say "Good Morning" to. The Mistress was pleased to see me and would say "Thank you," more times than I can remember. I really enjoyed this first job, but it came to an end when the lady was left a large house in an uncle's will. She wanted me to live-in, but I couldn't take that on again. So I left.

*

One very cold day, when I was in another daily job, the mistress said to me "How would you like to have a trip to London tomorrow? I want to go to Harrods." Well, I had never been to London. Let alone Harrods, as the world knows, the top shop.

She went on, "My daughter was coming, but at the last minute she can't, and I have just got to have a fur coat." She said, "Put on your best clothes and we will make an early start." I only had one coat which they gave me from the Homes and in this cold weather I wore that to work and on Sundays. I kept it clean and well brushed.

So the next morning I gave my shoes which were very worn an extra clean, with my black knitted stockings. I did look clean and tidy, but I could tell on Madam's face she wasn't very impressed. I knew by her quick walk she wanted me to walk well behind her to the station. And I didn't sit near her in the train. I don't think she wanted anyone to know she knew me. She didn't talk to me. She got a taxi at Charing Cross to Harrods. My first taxi ride. We went into Harrods, the doorman in uniform making a great fuss of her. I crept in unnoticed well behind her. She walked in as if she owned the place. It was a dream to me. I was looking at the prices on the clothes and thinking nobody has that much money to spend. The dresses were very lovely but cost more money than I earned in a year.

Princess Diana's Harrods

Madam told me to sit on a chair while she went into the fur department. She was in there ages.

I saw her coming out with the man who was attending to her. She was furious, shouting quite loud, "How can the management treat her so. Was the man sure they knew who she was, and how did they expect her to go through the winter without a fur coat." The man was so embarrassed, saying, "Your account is already well overdrawn, Madam. I'm very sorry." She kept on and on, saying, "They can't refuse me." She turned her back on the man and said, "I'll take it to the top and I'll be back." Poor man. He flew. I couldn't make out why she thought they ought to let her have the fur coat when she had no money to pay for it.

Needless to say we caught the next train back in silence. Madam dismissed me at the station, saying, "I won't need you anymore today." That day I learned a bit of how the other half lived.

*

In all the places I worked they didn't have any labour saving gadgets. Carpets were always sprinkled with used tea leaves and with a stiff brush. I went down on hands and knees brushing hard on every inch of the carpet. The tea leaves were to stop the dust from rising but, of course, there was dust everywhere. It was very hard work and a back-aching job.

One day a man came round where I was working with a Hoover vacuum cleaner and asked if he might give a demonstration. Madam was very indignant. "No, she wouldn't need a demonstration. Her carpets were always kept very clean." But the man knew different. If the carpets had never been vacuum cleaned he was in for a field day. At last she let him in, talling him he would find no dirt on her carpets. She made sure they were always kept clean.

Needless to say the Hoover bag was full of dirt in no time at all. And by the time he had finished all the carpets looked new.

I'll never forget the look on Madam's face when he showed her all the dirt. I think she thought he must have brought it in with him. She bought a Hoover cleaner and said I could use it once a month. She didn't trust it being used more often. She was sure it would wear out the carpets.

*

Daily jobs were not easy to find. I had a rough time between jobs. There were days when I didn't eat at all - no Supplementary Benefits in those days! I managed to get some lesser daily jobs, working a week here and a week there, and staying longer if I liked the mistress or if she liked me. I look back on that time with happy memories. It was still all work and no play but I was treated as someone and I enjoyed what I was doing.

In the meantime the country was talking about war, but surely it would never come. 1938 came and went. Prime Minister Chamberlain waved his piece of paper and said "Peace in our Time," and we thought all would be well. Then one morning in August, 1939, the lady I was working for said, "Rose, you will sleep in. I can't be alone if war comes." I said, "On, no. I couldn't do that." "I order you to," she demanded. I went home with a heavy heart. I put my key in the front door and there on the mat was a buff envelope with " ON HIS MAJESTY'S SERVICE ." Here were my calling-up papers. I was to report to a nearby army barracks by ten in the morning of that day. But the time had passed. I rushed to the barracks to explain I had just received the letter. They told me to report the next day. I had just spent my last day in domestic service for a mistress, and servant life would never be quite the same again.

The next morning at ten, I had started my journey to my first army camp. I was to spend the next seven years in the A.T.S., then marry and have a daughter, eventually grandchildren. But that would be another story.

When I was asked to join a party from another church, by a most loved priest who had left our church after eleven years, I laughed and said it was impossible. Those kind of funds needed for such a holiday had never come my way. I had spent years looking after my ill husband. But I kept on thinking about it all that day and thinking turned into praying and I was getting quite excited about the thought of going. I went to bed that night still with prayerful thoughts of the Holy Land on my mind. Yes, I was going, I knew, before falling asleep. All was well, I thought, I would be on that pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Next morning, first post, there was the cheque for just the amount needed, no more, no less. It was due to me from the insurance after my husband died. Coincidence? Well, maybe, but to me it was an answer to my prayers. I was full of joy. How good the Lord is. So there I was on the jet with twenty-five others and we were duly deposited on the runway at Tel Aviv with an almighty bang, bounce, and slither, during which we all died a thousand deaths. I think we wondered if we might be the next day's headlines. Moments later as we came to a safe halt, a voice devoid alike of apology, explanation or humour declared "We have just landed at Tel Aviv. Welcome to Israel." It was two o'clock in the morning. We traveled by coach to a silvery Jerusalem, lovely in the moonlight. Our hotel, aptly named "Panorama", looked across the Kedron Valley to the Mount of Olives with the heavenly city spread out beneath. Golden indeed at sunrise and sunset, Jerusalem in the glare of midday took on a harder look. One cannot move around the Holy Places and be unaware of underlying pain.

And when he was come near he beheld the city and wept over it. Surely today Jesus still weeps over Jerusalem and the world. We visited many places and of course would have loved to have stayed much longer at each place; being with an organized group this was not possible. But we were always albe to celebrate Mass, pray and sing hymns in some most wonderful places and for us all this was the heart of the tour. The tranquil stillness of the Garden of Gethsemane with ancient olive trees would seem to be unchanged, just the place to rest and meditate on the glory of it all. We went to the top of the Mount of Olives. Next we saw the site of the house of Caiaphas, the scene of Christ's trial before the High Priest and of Peter's denial. We visited the Pool of Siloam which Jesus told the blind man whom he healed to visit.

We followed the Way of the Cross, stopping before each station for a verse of scripture and a prayer. We went winding through the narrow, cobbled streets past dark little shops seething with humanity pressing their wares. We came to the Crusader Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the site of Jesus' Crucifixion at Calvary, and of his burial. There were many lamps decorating the Holy Places, the slab of rock where the anointing took place, the Empty Tomb, ornate, commercialized, noisy. Outside more noise and confusion. We saw the Wailing Wall, all that remains of Herod's Temple destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70. Close by is the beautiful Muslim mosque, the Dome of the Rock, built around a great rock believed to be the place where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice Isaac. We had to leave our shoes and bags on the ground outside in the care of our Arab courier - a Muslim. "Pray for the peace of Jerusalem," he told us.

We drove to the Shepherd Fields and entered in a cave before going to Bethlehem to the longest-standing church in Christendom, that of the Nativity. Inside the church one steps down into the cave where Christ was born. Mentally, one has to strip away much ornamentation before beholding the birthplace and the manger.

We set off on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho on our expedition to the Dead Sea past the Inn of the Good Samaritan and through the desert. I was very interested in this, having had to learn off by heart the parable of the Good Samaritan before breakfast one Sunday morning when I was eight. Never has the Bible come so vividly alive. In this cruel landscape of rocks, boulders and fields of sharp stones, beneath a pitiless sun, phrases flashed into the mind at every turn of the road: "Lest at any time thou dash thy foot against a stone," and "The shadow of the great rock in a weary land." By the side of the road a sign said "Sea Level". We continued steeply down-hill until we reached the lowest place on earth - the Dead Sea. On the western shore we saw the cave at Qumram where in 1947 an Arab shepherd boy discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls. We reached the mighty excavated fortress of Masada by cable car. For light relief most of us plunged into the Dea Sea. It was a very funny feeling floating on top. Trying to get out was very difficult; legs went anywhere but down; one couldn't stand up. After a long while we managed to stumble out and cleaned ourselves of the salt water under the fresh water showers dotted about the very stony beach. On the return journey we stopped at Bethany, home of Martha and Mary (there was even a cafe there called "Martha and Mary"!), we visited the tomb of Lazarus down very steep stairs cut in the rock.

We next travelled from Jerusalem to Galilee. We stopped at Jacob's Well and had a drink of its water. The well was miles deep. I was aware of the woman Jesus asked for a drink of water from the well, and of his answer to her. He knows all about me, too. We stayed three nights at the Lakeside Hotel at Tiberias, visiting Nazareth where we saw the Church of the Carpenter Shops and the Church of the Annunciation and St. Mary's Well where we watched baptisms. We went past the home of Mary of Magdala. Then to the Mount of the Beatitudes which was a wonderful experience with Eucharist in the open air and listening there to the Sermon on the Mount. On toTabgha, site of the Feeding of the Five Thousand, and the Church of the Rock, scene of Peter's Primacy; then to the site of Peter's fisherman's cottage and a very old synagogue where Jesus preached to the people.

We walked through old streets to the Basilica of the home of the Holy Family, then back to the coach and on to Cana in the dark. A little Friar showed us round the Church of the Miracle of Water into Wine and we saw large water pots. Finally back to the hotel, exhausted.

The next day we went to the Jordan. It was a beautiful day. We had our Eucharist by the waterfall of great beauty. We had to go down many steps to get to the water, so we were not in a great hurry to leave, though the time-table was very tight. We filled our bottles of water to take home. My granddaughter was baptized with water from the River Jordan. I was very proud of that.

Then, encircling the Lake, we passed over the Golan Heights to a kibbutz for lunch. We returned to Tiberias by the steamer. Then back to the Sea of Galilee for a gorgeous swim, which I did the three days at six in the morning at the hotel at Tiberias. Most nights we returned back to the Hotel quite late. The days were very full. I'm sure we saw as many places in a week as most people see in two weeks, but that did not stop us, after the evening meal, getting together and talking over the happenings of the day, though we were tired and ready for bed.

In Jerusalem, one night, after prayers, Father Michael had said, "It's a lovely evening and the moon is full. Who would like to climb the hill to the Mount of Olives." We looked at one another and said, "Why not? Our last chance." So off we went into the warm evening and it was worth the climb to the top, tiredness forgotten. The moon was so bright we could see each other. Father Michael said, "How many times Jesus must have stood just where we are standing now." It made us feel very humble and we bowed our heads in silent prayer, than sang a hymn, just as Jesus might have done with his disciples, then made our way down the hill to fall into bed.

We started our last day, Sunday at 7:30 in the

morning, with Eucharist celebrated in the hotel garden, again

overlooking the Lake of Galilee. Of course we sang, "Morning

has broken," and "Dear Lord and Father of Mankind." We set out

on our journey to Tel Aviv passing the Mediterranean. So my

prayers were answered.

.

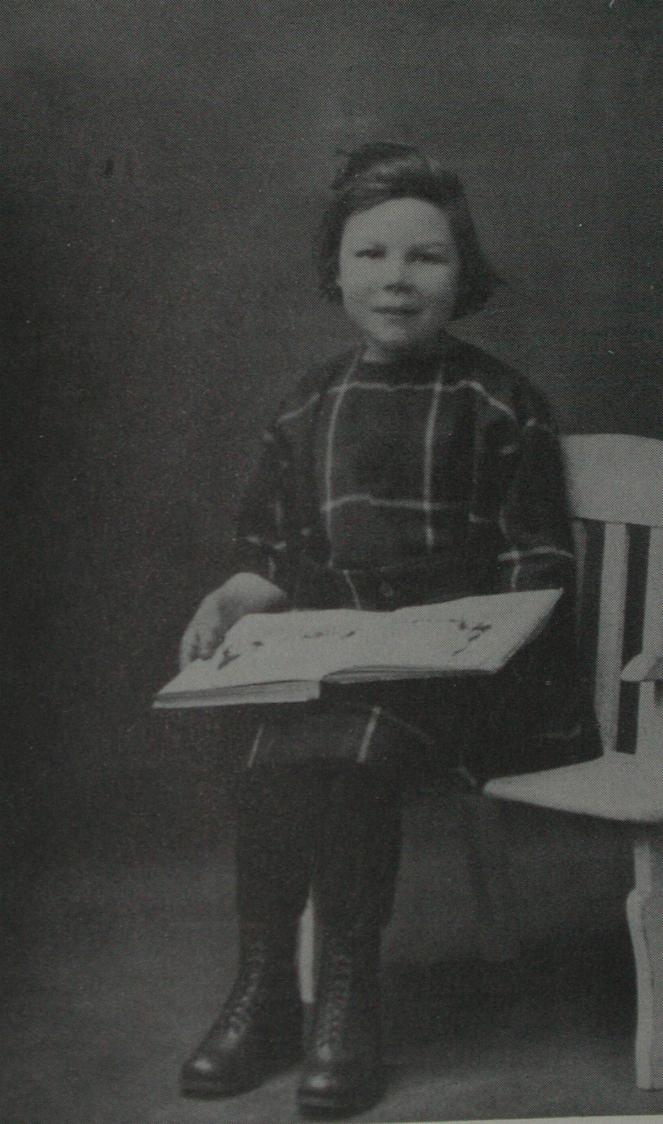

A photograph of me was taken for George. He paid for

it to be sent to him when I was nine years old. I was wearing

a scotch dress and I was allowed to wear it afterward, instead

of the navy blue we always wore. No ribbon for my hair, only a

boot lace.

*

Rose wrote down these stories for me. I still have the sheets written out in her clear longhand on exercise paper. I tried to get Virago Press to publish the book. But they responded that such a person could not have written this material. Our absurd English class structure, with Plato's Myth of the Metals tied around its neck like a millstone. Rose's education had been good. The hope, then the discouragement that came with the rejection, was not good for Rose.

But that would be another story, a story Rose did not live long enough to tell . . .

Let that story be told by the next generation, by Georgina, Rose's daughter, and by Carol Ann Rose, George's daughter.

The stories in this book are very familiar to me, my mother having told them many times. We have laughed and cried, and I marvel at how she survived. I know the scars must have been very deep, for as a child I remember her sleep walking and being woken by her screams in the night.

Yet the love of our Lord Jesus overcomes all things. Her Christian faith lifted her above bitterness, hatred and resentment. I really had the best mum in all the world.

We first visited the church where Dad sang in the choir, and although it had been bombed in the war and apparently looked different now than it did then, I felt a little closer to Dad being there. We then went to the school they had attended. It appeared much as I had anticipated - a three storey brick structure, built around 1900. The main difference was that all the gates and fences were gone and there was a wide open play yard now. The fences were of particular importance to me, as it was through a hole in one of these that my father had watched regularly to find his sister. The cinder path was still there at the edge of the yard, though, a reminder to times past. Dad has a cinder embedded in his hand to this day from a fall on that path.

On up the road we walked to the cottage that had been home to my Aunt for so many years. Originally, there had been fifteen cottages where all the girls in the Home had lived, each named for a tree, and Aunt Rose remembered and recited them all. One of the cottages had been bombed during the War, but the remaining fourteen have been beautifully restored and refurbished and are now prime real estate. We stopped in front of Aunt Rose's cottage, "Mulberry," for a photo, but didn't go in as it was now a private residence. Next we proceeded to the "Limes," one of four buildings that had housed the boys, fifty to a building. It, too, had been beautifully refurbished and now housed six luxury apartments with the first and second floors open for viewing (the third floor was occupied). The real estate agent was very kind. He told us to take our time and to look around wherever we wanted - and that the pool and gymn were open as well.

In the "Limes," all that we could find that was original was the staircase and two fireplaces. Aunt Rose said that Dad would never recognize it. There was a model suite quite exquisitely done, and it was obvious that here too a Cinderella job of renovating had taken place. We stopped in the hall for a picture of me standing under the staircase with my hands on my head, in the same spot where Dad had stood in his nightshirt and bare feet for punishment. Later, when I showed Dad the picture he laughed, but didn't want a copy as it evoked bad memories. Our next stop was at the gymn and swimming pool. Once again, they had been renovated and were quite posh.

Then on to the "Hollies," which had once been the dreaded Headmaster's house. It had been purchased for refurbishing as well, but was currently a sorry sight. The windows were smashed and the doors all boarded up. Aunt Rose took us around back where they used to have their field days on the grassy area. The grass was cut and well kept but the gardens that once surrounded the "Hollies" were now reduced to a bramble. Aunt Rose said that it was "a bit of a twist" as once the "Hollies" had been the prettiest place there, but now looked the worst. She looked for a pathway that she remembered from her youth to take us back to where we came in, and it was still there.

As we walked down the path, I felt very good for having come to see all that we had seen. I could now put a backdrop to all the stories Dad had told me of his youth. I am very thankful, too, for the hole in the fence. Had it not been for that hole, I may never have met the gracious and gentle lady I knew and loved as my dear Aunt Rose.

Rose waving her brother 'Good by'.

This story is from the collection of essays on story-telling, Tales within Tales: Apuleius through Time , ed. Constance S. Wright and Julia Bolton Holloway (New York: AMS Press, 2000), pp. 157-164, republished with their permission. To Order, see 'Whole Earth Catalogue '.

Georgina Peacock has now added to the account this material:

Rose and George Harris

When checking workhouse records for Greenwich Union, I found that Rose and George Harris had been admitted at regular intervals over a period of 18 months in 1913 and 1914. I also found they had a sister Doris born 1913. Their parents Thomas Harris and Rose Harrison had come into the workhouse with them, although Thomas had been sent away again as an ‘able bodied man’!

Prior to admittance they had lived in Griffin Street Deptford, in accommodation which had been condemned 25 years earlier. There was a soap factory at the end of the road and the smell hung heavily over the area. Records show that the children were starving and very ill on every occasion of admittance; the records also show that their mother was badly bruised and that she had the ‘smell of drink’ about her. Doris died aged 10 months from measles. When George and Rose were brought in for the last time, Rose went to the Park Hospital, Hither Green Lane, Lewisham. This, at that time, was a fever hospital. She was there for 9 months. George was in Calvert Road, a children’s hospital home. Rose was discharged to Calvert Road from the Park Hospital. Their mother is shown to be with them up until the time they were sent to the Hollies. Neither parents were seen again.

George, I think, must have experienced a mother’s love at some time in his early life. George died in Canada aged 93 years. His lifelong wish was to find his mother, then later to find her grave. He never achieved this. His experiences at the Hollies stayed with him all his life. He was never able to forgive or forget – all his life he wrote to my mum about the unkindness, cruelty and humiliation he experienced. I remember my mum often wrote to him, or said to him when they met, ‘It’s a long time ago, George, you must move on’. But I don’t think he ever did.

My mum Rose never knew the love of a family home, she only knew Sidcup Homes, I have since learned that after leaving the home she became a Girl Guide leader at St Mark's Church in Lewisham, I have spoken to old Guides who told me that she would never make any secret of the fact she was brought up in an orphanage. She would tell them how lucky they were to have the love of a family, and would also often invite girls from Sidcup to come over to be entertained by the Guides and have tea with them. Unlike Uncle George, my mother was not interested in finding her mother; she had the opinion that if her mother did not want her, then why should she want her mother! My mum had a hard life, there was no happy ending, but she survived. In the army she had commendations for work well done. She worked to the top of her profession as a cook, and she was an excellent cook. She was a lovely mum and a wonderful grandmother. She was married for 42 years and although it was not happy she stayed with my dad! She would always say ‘No one looks after you, like you do yourself’. She always got up, dusted herself down and carried on! She was a religious lady, each day Morning and Evening Prayers were read and learned at Sidcup, this sustained her throughout her life, through good times and bad.

Georgina Peacock

This story is from the collection of essays on story-telling,

Tales within Tales: Apuleius through Time , ed.

Constance S. Wright and Julia Bolton Holloway (New York: AMS

Press, 2000), pp. 157-164. To Order, see 'Whole

Earth Catalogue'.

It has most recently been published The Hollies: A Home for Children, ed. Jad

Adams and Gerry Coll (London, 2005), pp. 75-95.

RETURN TO 'AN

ENGLISH ROSE', PART I

OLIVELEAF WEBSITE || UMILTA WEBSITE || OLIVELEAF WEBSITE || JULIAN OF NORWICH, TEXT AND CONTEXTS,

WEBSITE || BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN,

REVELATIONES, WEBSITE || CATALOGUE

AND

PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK

REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||

FLORIN WEBSITE ©1997-2024

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

OLIVELEAF PORTAL

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |