The Ruthwell Cross, Scotland

he earliest written English

poem is the 'Dream of the Rood' inscribed in runes upon a

stone cross in Scotland. This booklet suggests its origins.

Its hard copy version, which may be ordered ,

gives the Runes of the Poem. The delight of being a pilgrim

scholar is in journeying to Carlisle, then across the border

from Hadrian's Wall to Bewcastle and Ruthwell to see these

ancient monuments, and then to Vercelli in Italy and seeing

its manuscript. None of the original versions of this poem

are today in England. Today, the English language in the

world's eyes, is the language of commerce, of power, of imperium,

like that of pagan Rome. We tend to forget its earliest

poem, centred most crucially upon the Cross

, upon spirituality.

Though I earlier made the claim that Hilda was

responsible for the Ruthwell Cross, even archeologically

embedded in this essay's title, I now believe that it is

specifically the result of Ceolfrith and Bede's mission to

King Nechtan in 710. (We recall that Ceolfrith was journeying

to Rome with the huge Codex Amiatinus

when he died in 713.) For my pilgrimage took me not only to

Ruthwell, Bewcastle, and Vercelli, but also to Florence, where

I organized an international conference of the Laurentian

Library's Codex Amiatinus, this changing my mind about my

earlier thesis. For Jarrow has the same inhabited vine

sculpture as has the Ruthwell Cross, copying classicizing

scuptural elements foreign to Hibernian or Anglo-Saxon work,

and Ceolfrith was specifically noted by Bede to have sent such

stone-masons skilled in Roman work to King Nechtan.

And now: Stop Press:

Having recently gone to Ravenna in order to perform in concert

the music of Dante's Commedia (http://www.florin.ms/Dantevivo.html),

I also revisited her splendid churches and the Diocesan museum

for their mosaics and carvings. In the museum I saw exactly

the same carving of the inhabited vine. Thus we can postulate

that, like the Codex Amiatinus copying Cassiodorius' in

Vivarium's library, the sculpture more likely is derived along

this axis of the Byzantine Ravenna of the Ostrogoths than of

Constantinople itself. Alas, the museum forbade the taking of

any photographs to prove the hypothesis.

Jarrow inhabited vine Ruthwell

inhabited vine

The elements comprising the Ruthwell Cross and that at

Bewcastle, as well as the famous poem in runes sculpted upon

Ruthwell, seem to come from all the cultural elements present

at Iona, Whitby, Lindisfarne and Jarrow, to be a glorious

mixture of Irish, Anglo-Saxon, and Byzantine styles, to be a

truly cosmopolitan gathering. Similarly Bede demonstrates, in

his writings, such a cosmopolitan gathering of materials.

I. Hilda, Cædmon and the Ruthwell Cross

Abbess Hilda was the great niece of King Edwin, being baptised with him by Paulinus, Augustine's associate, at York Minster (A.D. 625). She spent the first thirty-three years of her life as a secular noblewoman, the second thirty-three years as a consecrated nun and abbess at Hartlepool, later coming to Whitby (+ A.D. 680). In these places she established the monastic life observing righteousness, mercy, peace and charity. Bede tells us that: 'After the example of the primitive Church, no one there was rich, no one was needy, for everything was held in common, and nothing was considered to be anyone's personal property. So great was her prudence that not only ordinary folk, but kings and princes used to come and ask her advice in their difficulties and take it. Those under her direction were required to make a thorough study of the Scriptures and occupy themselves in good works, to such good effect that many were found fitted for Holy Orders and the service of God's altar. Five men from this monastery later became bishops.'

At Whitby the cowherd Cædmon was too ashamed to sing in turn to the harp the pagan lays, such as Beowulf, that the others sang. But one night he received a vision in which he was told by an angel to sing of the Creation of the World. Like Mary at the Annunciation he protested his unworthiness but then obeyed. Bede records the song he sang for the angel and for Hilda.

raise we the Fashioner now of Heaven's fabric, The

majesty of his might and his mind's wisdom, Work of the

world warden, worker of all wonders, How he the Lord of

Glory everlasting, Wrought first for the race of men Heaven

as a rooftree, Then made he Middle Earth to be their

mansion.

raise we the Fashioner now of Heaven's fabric, The

majesty of his might and his mind's wisdom, Work of the

world warden, worker of all wonders, How he the Lord of

Glory everlasting, Wrought first for the race of men Heaven

as a rooftree, Then made he Middle Earth to be their

mansion.

Lindisfarne was settled from Iona (A.D. 635), the English Church in Northumbria, unlike that in Kent, maintaining good relationships between Celts and Anglo-Saxons. The Celts had been Christianized long before, the Anglo-Saxon invaders and settlers only recently becoming converted to Christianity. From Hilda's Whitby went missioners to complete that task, especially along Hadrian's Wall. At Bewcastle and at Ruthwell stand seventh-century Anglo-Saxon preaching crosses, the first celebrating peace-weaving marriages between Christian and pagan Anglo-Saxon kings and queens, the second having on it, in Anglo-Saxon runes , the poem of ' The Dream of the Rood'. Ruthwell, just across the border in Scotland, was only under Anglo-Saxon control until A.D. 685. 'The Dream of the Rood' is likely Cædmon's composition. Its pagan counterpart may be found in the Havamal, where Odinn learns the runes of life by being hanged upon the tree Yggdrasil for nine days and nights. Centuries later 'The Dream of the Rood' was revised by Cynewulf and is to be found in a manuscript left by an English pilgrim at Italian Vercelli, along with Cynewulf's other works, such as a poem on St Helena , the British slave mother to the Emperor Constantine, who, in the legend, discovered the True Cross in Jerusalem. That scene is sculpted on another stone cross, at Kelloe.

Hilda's Abbey library contained the writings of Jerome. Jerome, assisted by

the Roman noblewomen, Paula and

Eustochium , who learned Hebrew for that task and who

already knew Greek as well as Latin, had translated the Bible

from Hebrew and Greek into Latin. He also wrote a charming

version of the Lives of Saints Paul and Anthony, telling how

even the lying, fabling, mythical Centaurs in the Egyptian

desert acknowledge Christ as Truth and Messiah, and including

the episode sculpted upon the Ruthwell Cross where the two

hermit saints squabble over who is the most courteous, each

refusing to take the first bit from the loaf brought them

miraculously by the raven. Finally they settle their dispute

and their hunger by together equally breaking the bread in the

wilderness. (A stone cross at Nunburnholme, showing its Abbess

with her booksatchel, has a mother and baby centaur beneath

the Nativity, similarly joking with Jerome's text.) Other

scenes on the Ruthwell Cross emphasize women, the Visitation,

where we see Mary greeting

Elizabeth , the penitent woman anointing Christ's feet ,

washing them with her tears, drying them with her hair (who

was not in this period associated with Mary Magdalen), the Annunciation to Mary

by the Angel, and the Flight into Egypt.

II. 'The Dream of the Rood' on the Ruthwell Cross and in the Vercelli Book

A. The Ruthwell Cross Version in Runes on Stone

The poem in runes on the Ruthwell Cross is the first written religious poem and prayer in English we have today (Bede's version of Cædmon's Creation Hymn is in Latin translation, not its Anglo-Saxon original), and, like the Hymn to the Creation, it is similarly a dream vision. The Roman Empress Helena, who likely came from York, where her son had been proclaimed Emperor, had commenced the practice and contemplation of pilgrimage to the Holy Places, to be followed in turn by women such as Paula, Eustochium, Fabiola, Marcella, Egeria and others. Emperor Constantine had himself been converted to Christianity, and converted the whole Roman Empire with him to Christianity, because of his Christian mother Helena and because of the dream vision he experienced (A.D. 312) of the Cross seen by him in the sky, prior to his victory over a pagan enemy. Northumbria's King Oswald (A.D. 634), a successor to King Edwin, then erected a cross prior to the Battle of Heavenfield in imitation of the Emperor Constantine.

The Anglo-Saxon Ruthwell Cross, reflecting Constantine and Oswald's crosses, allows those who see and read it to contemplate in turn each place concerning the life of Christ, Nazareth, the Egyptian Wilderness, the Jordan Wilderness, Galilee, and Jerusalem, culminating with the Crucifixion. It is a map of the Holy Places that pilgrims may read. The runes of the 'Dream of the Rood' inscribed about their edges, their margins, describe the writer, likely Cædmon, dreaming of the Cross speaking to him, narrating of the wood and blood and of the sacred burden it had once borne; then, in Cynewulf's longer version, of its being turned into the sacred reliquary bedecked by the Emperor Constantine with gold and rubies at Constantinople. Jerome, whose works were read at Whitby, had practiced contemplating upon the Crucifix , becoming himself as naked as the naked Christ, in his 'imitatio Christi'. So here does Cædmon, if he is its author, in his contemplation meet with the blood-stained wood of the Roman gallows (Anglo-Saxon 'galgu') erected once to hang Jesus, the Christ, the King of the Jews. So does Cædmon's poem, and its Cynewulfian revision, today have us converse as pilgrim visionaries with the ignoble gallows and imperial reliquary of God.

The poem is shaped in two forms, both used in

Anglo-Saxon Riddles. It begins with the dreamer saying 'I

saw', then has the inanimate object speak, telling its

observers, its poet and its readers, 'I am'. There are such

Anglo-Saxon Riddles spoken by 'Book', by 'Cross', etc. In a

sense it, too, is the mocking titulus placed above

the Cross , 'Jesus, King of the

Jews'.

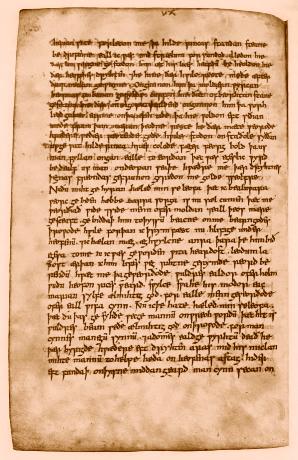

B. The Vercelli Manuscript Version on Parchment (see http://www.dreamofrood.co.uk/, http://www.english.ox.ac.uk/coursepack/rood/index.html):

The longer version is given from the manuscript left

by an Anglo-Saxon pilgrim in Vercelli, Italy, the rubricated

lines being those given in the rune on the Ruthwell Cross.

Adapted from the translation by Michael Alexander.ear, while I tell of the best of dreams . which came to me at midnight

when humankind kept their beds.

It seemed that I saw the Tree itself . borne on the air, light wound round it,

brightest of beams, all that beacon was . covered with gold, gems stood

fair at its foot, and five rubies . set in a crux flashed

from the crosstree. Around angels of God . all gazed upon it,

since first fashioning fair . It was not a felon's gallows,

for holy ones beheld it there . and men, and the whole Making shone for it

Trophy of Victory . I, stained and marred,

stricken with shame, saw the glory-tree . shine out gaily, sheathed in

decorous gold; and gemstones made . for their Maker's Tree a right mail-coat

Yet through the masking gold I might perceive .

what terrible sufferings were there

It bled from the right side . Ruth in the heart

Afraid I saw that unstill brightness . change raiment and colour,

again clad in gold or again slicked with sweat . spangled with spilling blood.

I, lying there a long while . beheld, sorrowing, the Healer's Tree

till it seemed that I heard how it broke silence, best of wood, and spoke:

'It was long ago-I still remember . back to the holt where I was hewn down;

From my own stock I was struck away . dragged off by strong enemies

wrought into a roadside scaffold . They made me a hoist from wrongdoers.

The soldiers on their shoulders bore me . until on a hill-top they raised me

many enemies made me fast there . Then I saw, marching toward me,

Mankind's brave King . He came to climb upon me. I dared not break nor bend aside . against God's will, though the ground itself

shook at my feet. Then the young warrior, Almighty God, mounted the Cross, in the sight of many. He would set free mankind.

I shook when his arms embraced me, but I durst not bow to ground,

stoop to Earth's surface . Stand fast I must.

I was reared up, a rood . I held the King, Heaven's lord, I dared not bow . They drove me through with dark nails: on me are the wounds

Wide-mouthed hate dents. I durst not harm any of them.

They mocked us together . I was all wet with blood sprung from the Man's side . after he sent forth his soul. Many wry wierds I underwent . up on that hilltop; saw the Lord of Hosts stretched out stark . Darkness shrouded the King's corpse.

A shade went out wan under cloud pall . All creation wept,

keened the King's death . Christ was on the Cross.

But there quickly came from afar . many to the Prince .

All that I beheld had grown weak with grief . yet with glad will bent then

meek to those men's hands . yielded Almighty God.

They lifted Him down from the leaden pain . left me, the commanders

Standing in blood sweat . I was sorely smitten with sorrow

wounded with shafts . Limb-weary they laid him down.

They stood at his head . They looked on him there .

They set to contrive Him a tomb . within sight of his bane

carved it of bright stone . laid in it the Bringer of Victory

spent from the great struggle . They began to speak the grief song,

sad in the sinking light . then thought to set out homeward;

their most high Prince . they left to rest with scant retinue.

Yet we three, weeping, a good while . stood in that place after the song

had gone up from the captains' throats . Cold grew the corpse, fair soul house.

They felled us all . We crashed to ground, cruel Wierd,

and they delved for us a grave . The Lord's men learnt of it, His friends found me.

It was they who girt me with silver and gold. . .

But now see http://www.florin.ms/aleph4.html#ruthwell

http://www.umilta.net/equal2.html

External Links:

http://www.visionarycross.org/

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2008/oct/23/the-egyptian-connection/?page=1

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND

ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF LOVE || HER TEXTS || HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE

AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |