he illustration of Christ healing a Blind Man is

taken from Myra Luxmore's 1912 painting, for which she used

the people and the landscape of today's Holy Land. The

clothing of the Blind Man (Bartimaeus?) is painted in the most

delicate, translucent shot silk green colours, colours

Bartimaeus cannot yet see. The artist, whose family were

friends of Gerard Manley Hopkins, was imagining being blind,

being without her God-given sight and artistry. Mother Agnes Mason, CHF, herself an

exquisite water-colourist, was

given this painting by her brother, Canon Arthur Mason.

he illustration of Christ healing a Blind Man is

taken from Myra Luxmore's 1912 painting, for which she used

the people and the landscape of today's Holy Land. The

clothing of the Blind Man (Bartimaeus?) is painted in the most

delicate, translucent shot silk green colours, colours

Bartimaeus cannot yet see. The artist, whose family were

friends of Gerard Manley Hopkins, was imagining being blind,

being without her God-given sight and artistry. Mother Agnes Mason, CHF, herself an

exquisite water-colourist, was

given this painting by her brother, Canon Arthur Mason.

Photograph, Revd. Kenneth Clinch, Chaplain General,

Community of the Holy Family

Sacrament and Gospel: Water, Wine, Bread, Oil

Essay for the Lambeth Diploma Greek Examination

Prologue

his essay discusses the

Sacrament in the Gospel in the light of Dom Gregory Dix's

sense in The Shape of the Liturgy that it is not so

much the Gospels that convey the sacrament of the Eucharist,

as it was liturgical practice, countering that argument with

Brooke Foss Westcott's observation, that 'in the other

Gospels we find our King, our Lord, our God; but in St. Luke

we see the image of our Great High Priest'. The essay

analyses the Gospel of Luke, and especially its Gospel

within the Gospel (Isaiah 61.1-2, Luke 4.18-19), and

concentrates upon the Gospel's use of such crucial and

quotidian elements of Mediterranean culture as water, wine,

bread, oil for the sacraments of baptism, of marriage, of

the eucharist, of anointing, in word and in deed. Luke has

Christ say that he gives us to know the mysteries of the

Kingdom of God (8.10), a Kingdom which, according to a

reading of the Lord's Prayer, is to be shaped on earth

(Matthew 6.11; Luke 11.2) as it is in heaven, a Kingdom

which Jesus tells the Pharisees is within us all (17.21;

Thomas' Gospel, 81.25). These ritual acts bring eternity

into the realm of time and liberty to bondage. With the last

sacrament, that of the oil of the anointing, the essay shall

return to where it had begun, to its Messianic theme of the

Great High Priest and of the Royal Priesthood, the Kingdom

of Priests, foretold by God to Moses (Exodus 19.4-6, Epistle

to the Hebrews, I Peter 2.9, Revelations 5.10).

his essay discusses the

Sacrament in the Gospel in the light of Dom Gregory Dix's

sense in The Shape of the Liturgy that it is not so

much the Gospels that convey the sacrament of the Eucharist,

as it was liturgical practice, countering that argument with

Brooke Foss Westcott's observation, that 'in the other

Gospels we find our King, our Lord, our God; but in St. Luke

we see the image of our Great High Priest'. The essay

analyses the Gospel of Luke, and especially its Gospel

within the Gospel (Isaiah 61.1-2, Luke 4.18-19), and

concentrates upon the Gospel's use of such crucial and

quotidian elements of Mediterranean culture as water, wine,

bread, oil for the sacraments of baptism, of marriage, of

the eucharist, of anointing, in word and in deed. Luke has

Christ say that he gives us to know the mysteries of the

Kingdom of God (8.10), a Kingdom which, according to a

reading of the Lord's Prayer, is to be shaped on earth

(Matthew 6.11; Luke 11.2) as it is in heaven, a Kingdom

which Jesus tells the Pharisees is within us all (17.21;

Thomas' Gospel, 81.25). These ritual acts bring eternity

into the realm of time and liberty to bondage. With the last

sacrament, that of the oil of the anointing, the essay shall

return to where it had begun, to its Messianic theme of the

Great High Priest and of the Royal Priesthood, the Kingdom

of Priests, foretold by God to Moses (Exodus 19.4-6, Epistle

to the Hebrews, I Peter 2.9, Revelations 5.10).

I: The Great High Priest and the Royal Priesthood

A. The High Priest in the Hebrew Scriptures

hree figures from the Hebrew Scriptures especially

represent the priestly role: Melchizedek, King and Priest of

Salem, who presents bread and wine to Abraham (Genesis

14.18-20, Psalm 110.4); Aaron, the anointed High Priest and

Levite brother to Moses and to Miriam (Exodus through

Deuteronomy, passim); David, the anointed Priest King (1

Samuel 16.11-13), all of whom can be seen to foreshadow

Jesus. Gentile Melchizedek does so by the generous act of

giving bread and wine to Abraham, an act that will be

reciprocated by Jesus' act of giving bread and wine and

flesh and blood in a sacrament that will reach out to

Gentiles as well as to Jews and be performed by them. Aaron

and the line of High Priests he begins do so by being the

sole persons to enter the Holy of Holies, containing the

Ark, of the Tabernacle, which will become the Temple, a

structure ritually involving both sanctified bread (the

manna kept in the Ark, and the bread of the presence to be

eaten only by priests), and the blood from sacrificed

animals. As for David, it was held that the Messiah, the

Christ, the 'anointed one', would be descended from him.

David, Luke's Jesus noted, ate and presented to his

followers the bread of the presence in the Temple, which was

only permitted for priests' use (6.4-5). Zachariah in his

prophetic book particularly spoke of the High Priest and of

the Messiah, giving the name of Joshua to his High Priest

figure and tracing the Messiah's descent from David, while

the circle about Paul, as evidenced in (Apollos'? Prisca's?)

Epistle to the Hebrews and the Epistle of St. Barnabas, as

well as Qumramic material, use the figure of Melchizedek.

hree figures from the Hebrew Scriptures especially

represent the priestly role: Melchizedek, King and Priest of

Salem, who presents bread and wine to Abraham (Genesis

14.18-20, Psalm 110.4); Aaron, the anointed High Priest and

Levite brother to Moses and to Miriam (Exodus through

Deuteronomy, passim); David, the anointed Priest King (1

Samuel 16.11-13), all of whom can be seen to foreshadow

Jesus. Gentile Melchizedek does so by the generous act of

giving bread and wine to Abraham, an act that will be

reciprocated by Jesus' act of giving bread and wine and

flesh and blood in a sacrament that will reach out to

Gentiles as well as to Jews and be performed by them. Aaron

and the line of High Priests he begins do so by being the

sole persons to enter the Holy of Holies, containing the

Ark, of the Tabernacle, which will become the Temple, a

structure ritually involving both sanctified bread (the

manna kept in the Ark, and the bread of the presence to be

eaten only by priests), and the blood from sacrificed

animals. As for David, it was held that the Messiah, the

Christ, the 'anointed one', would be descended from him.

David, Luke's Jesus noted, ate and presented to his

followers the bread of the presence in the Temple, which was

only permitted for priests' use (6.4-5). Zachariah in his

prophetic book particularly spoke of the High Priest and of

the Messiah, giving the name of Joshua to his High Priest

figure and tracing the Messiah's descent from David, while

the circle about Paul, as evidenced in (Apollos'? Prisca's?)

Epistle to the Hebrews and the Epistle of St. Barnabas, as

well as Qumramic material, use the figure of Melchizedek.

B. The Context of Luke's Gospel

t is generally agreed in the scholarship that by

Jesus' day the Levitical priesthood, descended from Aaron

either directly or by lot to make up for the lost families

of the exiles, such as that of Abijah or Abia (1.5),

exercised a tyrannical religio-financial stranglehold upon

Judaism. This was exacerbated by the argumentation over the

Law by the Pharisees ('Separated'), actually the Hasidim

(meaning 'Merciful, Pious, Good') who broke away from the

Sadducees, and the Sadducees (Zadok, 'Righteous' or, more

likely, descendants of Zadok the High Priest), each opposing

the other and polarising the issues, the Rabbinical

Pharisees centering upon their Levitical observances, the

Hellenised Sadducees being more worldly, an argumentation we

observe in the Gospels' pages. In Jesus' day, the High

Priesthood of the Levites was in the domain of the

Hasmonaean/ Maccabaean Sadducees, from whom the Hasidim had

defected. So serious was the tension that the more righteous

Hasidim, the Essenes of the Qumram scrolls (150-140

B.C.-A.D. 68), established themselves as a separate and

monastic 'counter culture' to official Judaism, breaking

from the Temple and its corruption, while the Zealots sought

to wrest back freedom through rebellion. One could add to

these factions the related ones of the Nazarites (who vowed

abstinence from wine and touching the dead and did not cut

their hair), the Galileans (proselytes and settlers much

prone to violent rebellion), and the 'Baptists' and

'Christians', the latter two the Jewish and then Gentile

followers of John and Jesus who in their sincerity are

closest to the Hasidim and the Essenes but who turn

Pharisean teaching inside out concerning hygiene and the

Sabbath (11.39-52). Moreover, the Galileans, who were mainly

Gentile converts to Judaism mixed with Jewish settlers,

seemed ill-mannered, uneducated in speech and unlettered in

the Law, to the Jews in Jerusalem and were greatly feared

because of their tendency to revolt (22.52,58-59). The

Galilean Jesus' followers included fellow Galileans, as well

as a Zealot and a Levite, and even, by Acts, a Pharisee

(Paul), a Baptist (Apollos) and Nazarites.

t is generally agreed in the scholarship that by

Jesus' day the Levitical priesthood, descended from Aaron

either directly or by lot to make up for the lost families

of the exiles, such as that of Abijah or Abia (1.5),

exercised a tyrannical religio-financial stranglehold upon

Judaism. This was exacerbated by the argumentation over the

Law by the Pharisees ('Separated'), actually the Hasidim

(meaning 'Merciful, Pious, Good') who broke away from the

Sadducees, and the Sadducees (Zadok, 'Righteous' or, more

likely, descendants of Zadok the High Priest), each opposing

the other and polarising the issues, the Rabbinical

Pharisees centering upon their Levitical observances, the

Hellenised Sadducees being more worldly, an argumentation we

observe in the Gospels' pages. In Jesus' day, the High

Priesthood of the Levites was in the domain of the

Hasmonaean/ Maccabaean Sadducees, from whom the Hasidim had

defected. So serious was the tension that the more righteous

Hasidim, the Essenes of the Qumram scrolls (150-140

B.C.-A.D. 68), established themselves as a separate and

monastic 'counter culture' to official Judaism, breaking

from the Temple and its corruption, while the Zealots sought

to wrest back freedom through rebellion. One could add to

these factions the related ones of the Nazarites (who vowed

abstinence from wine and touching the dead and did not cut

their hair), the Galileans (proselytes and settlers much

prone to violent rebellion), and the 'Baptists' and

'Christians', the latter two the Jewish and then Gentile

followers of John and Jesus who in their sincerity are

closest to the Hasidim and the Essenes but who turn

Pharisean teaching inside out concerning hygiene and the

Sabbath (11.39-52). Moreover, the Galileans, who were mainly

Gentile converts to Judaism mixed with Jewish settlers,

seemed ill-mannered, uneducated in speech and unlettered in

the Law, to the Jews in Jerusalem and were greatly feared

because of their tendency to revolt (22.52,58-59). The

Galilean Jesus' followers included fellow Galileans, as well

as a Zealot and a Levite, and even, by Acts, a Pharisee

(Paul), a Baptist (Apollos) and Nazarites.

Over all these factions and sects was the further

tyranny and menace of foreign domination, of the Roman Empire,

which renamed Israel 'Palestine' (after the hated Philistines)

and which would, in A.D. 68, destroy Essenic Qumram , in A.D. 70,

raze the Jerusalem Temple of the Herodian Sadducees to the

ground, an event Jesus in Luke's text emphatically prophesies,

13.31-35, 19.41-44, 21.5-6, 20-24, 23.27-31, accurately

describing the events the eye-witness Josephus likewise

recounts, and, in A.D. 74, wipe out the Zealots' Masada, which

Herod the Great had built earlier to defend himself against

his Jewish subjects. Though he also rebuilt the Temple he was

not himself Jewish but an Edomite, in Latin, an Idumaean. His

son, Herod Antipas, Tetrarch by Roman appointment of Galilee,

had John the Baptist executed, albeit reluctantly, and, along

with Pontius Pilate, the Roman Procurator (of taxes) did not

stop the crucifixion of Jesus, a crucifixion much desired by

the Priests, Levites and Scribes, and the Sadducees and

Pharisees, whom Jesus was castigating for their damage to

Judaism.

C. The Royal Priesthood in Luke's Gospel

uke's Gospel has for theme the Kingdom of God,

whose Messianic Priest King gives to his subjects, his

followers, his own Royal Priesthood. Fittingly the Gospel

begins with a priest (1.5-23) and ends with the laity

(24.53) in the Jerusalem Temple. It begins with a priest

named Zachariah or Zechariah, whose name in Hebrew means

'God remembers', and the Annunciation to him by the angel

Gabriel of the coming birth of his son, John the Baptist.

Zachariah and his wife Elizabeth (Elisheba) are both

blameless (Luke 1.6), as in Ps. 119.1, 'Happy are they whose

ways are blameless, who walk in the law of the Lord'.

Moreover, Zachariah's wife is descended directly from Aaron,

the Greek noting she is 'the daughter of Aaron', (1.5), but

she is aged and childless. From Exodus 6.23, we know she

also bears the name of Aaron's wife, Elisheba. Zachariah in

the Temple is told by Gabriel that his wife Elizabeth will

bear him a child in their old age, paralleling her to Sarah

and Hannah (and Isaiah 54.1). Because of Zachariah's

incredulity he is struck dumb - and thus we learn that not

only he but also Elizabeth are literate, necessary for

members of the priestly caste, for she knows that their

child is not to be named after his father, but instead to be

given the unusual name of John. Zachariah could only have

informed her of this angelic and deific command in writing,

as he also informed their neighbours in this manner at the

time of his son's circumcision on the eighth day according

to Jewish Law (1.60-63). Interestingly also, because both he

and his wife are of priestly stock, their child, unlike

Mary's Jesus at the Presentation in the Temple, does not

need to be redeemed.

uke's Gospel has for theme the Kingdom of God,

whose Messianic Priest King gives to his subjects, his

followers, his own Royal Priesthood. Fittingly the Gospel

begins with a priest (1.5-23) and ends with the laity

(24.53) in the Jerusalem Temple. It begins with a priest

named Zachariah or Zechariah, whose name in Hebrew means

'God remembers', and the Annunciation to him by the angel

Gabriel of the coming birth of his son, John the Baptist.

Zachariah and his wife Elizabeth (Elisheba) are both

blameless (Luke 1.6), as in Ps. 119.1, 'Happy are they whose

ways are blameless, who walk in the law of the Lord'.

Moreover, Zachariah's wife is descended directly from Aaron,

the Greek noting she is 'the daughter of Aaron', (1.5), but

she is aged and childless. From Exodus 6.23, we know she

also bears the name of Aaron's wife, Elisheba. Zachariah in

the Temple is told by Gabriel that his wife Elizabeth will

bear him a child in their old age, paralleling her to Sarah

and Hannah (and Isaiah 54.1). Because of Zachariah's

incredulity he is struck dumb - and thus we learn that not

only he but also Elizabeth are literate, necessary for

members of the priestly caste, for she knows that their

child is not to be named after his father, but instead to be

given the unusual name of John. Zachariah could only have

informed her of this angelic and deific command in writing,

as he also informed their neighbours in this manner at the

time of his son's circumcision on the eighth day according

to Jewish Law (1.60-63). Interestingly also, because both he

and his wife are of priestly stock, their child, unlike

Mary's Jesus at the Presentation in the Temple, does not

need to be redeemed.

Enmeshed with Luke's accounts of the conception and birth of John to Zachariah and Elizabeth in Judah, near Jerusalem, are those of the conception of Jesus by Mary through the message (Evangel, Gospel) of Gabriel in Nazareth and of his birth to Mary and Joseph in Bethlehem. Mary, following the Annunciation , hastens to visit her cousin Elizabeth who, the text of Luke tells us thrice (1.24,26,36), is in the sixth month of her pregnancy. Thus it is under the authoritative, privileged and priestly roof of Zachariah and Elizabeth in the hill country, likely in priestly Hebron near Jerusalem and its Temple, that two Messianic psalms of rejoicing are sung, the first by Mary, the 'Magnificat', the second by Zachariah, the 'Benedictus,' which in the Christian liturgy have been taken into Evening and Morning Prayer, Vespers and Lauds. Next, the child Jesus, who was born in David's city of Bethlehem, and who was greeted by shepherds and, in Matthew, by kings (David having been both), is presented in the Temple as the first-born male child opening his mother's womb. Because she is poor, she presents not a lamb but only a pair of turtledoves or two nestling pigeons. To do so she ascends the fifteen steps from the Women's Court to stand on the threshold of the Court of Israel.

There, in the priestly setting in which Zachariah had already been visited by Gabriel, Mary, Joseph and Jesus are greeted by Simeon and Anna, both elderly and devout denizens of the Jerusalem Temple, who clearly recognise him as the Messiah descended from David. Simeon is spoken of as 'eusebius' (2.25), 'taking well', reverent, devout, and his prayer has been granted that he should see Israel's Messiah before his death (2.26). (Joseph of Arimathea, the member of the priestly Sanhedrin, at the opposite end of the Gospel will likewise be one awaiting the Kingdom of God, 23.51). Simeon reverently, sacramentally, holds the child in his arms. That word is used again by Luke, in Acts 2.5 of the Pentecost, and 8.2, at the stoning of Stephen. It occurs also in the Epistle to the Hebrews 12.28. Though Prophetess Anna's Psalm is not given, the Hebrew Scriptures' Psalm that Hannah had sung in the Temple having been given by Luke to Mary for her 'Magnificat', this prophetess actually bears the same name, Anna, meaning 'grace,' as does Hannah of Samuel 1.20, and the Greek text writes her name so, aspirating the a with an h. Luke stresses her descent as a daughter of Phanuel (Face of God), of the tribe of Aser. Thus Luke has been at pains to stress men and women equally in priestly and prophetic contexts at the opening of his Gospel.

In these crucial opening chapters to Luke we see Jewish liturgical customs being carried out with two families, one of them influential, elitist and priestly, the other poor, of the people, yet kingly. We will again see this harmonising and equalising of priest and lay where Jesus, at twelve years of age, sits with the Temple's scholar priests as their intellectual equal (2.46-47). It has been noted that Jesus' questioning of the elders is in accord with the Passover custom that the child initiate the feast with his question concerning its meaning. The elders, at Passover, would be particularly ready to listen to a child's question and to be drawn into dialogue. To this day in Synagogue the young and the old are equal before God. Then the words concerning Jesus' upbringing on his return home to Nazareth echo those concerning the child Samuel in the Temple (2.52, 1 Samuel 2.26).

But in the process first of Luke's Gospel, then of Acts, we witness an undoing and then a recreating of Jewish customs, which in Jesus' time had become an intolerable burden to the Jewish laity. What emerges in this development are the Christian sacraments promulgated by Jesus as the Priest King for both Jews and Gentiles. We see first John, born of priestly parents, rejecting soft clothing and wealth (3.11, 7.25; Thomas' Gospel 94.28-95.2), which the Jewish priesthood could expect from their rich revenues derived from the taxation of their laity, and his fasting in poverty in the Wilderness about Jordan. We see Jesus join his cousin, then withdraw himself to the Wilderness above Jericho and fast and pray, and then we hear him read Isaiah 61.1-2 in the Synagogue and next witness how he, in his own words now, preaches Hannah's Song and Mary's Magnificat and John's 'kyrygma' based on Isaiah 40 and his own based on Isaiah 61, in the form of the Beatitudes.

The descent of Jesus from David is stressed many times in Luke's Gospel and elsewhere. Matthew began with Jesus' genealogy (1.1-17). Luke waits until the third chapter of his Gospel to introduce his version of the genealogy and his version differs from Matthew's in several ways: it is presented in the reverse order; it traces Jesus' ancestry beyond David through Adam to God, making him explicitly both 'son of David,' and 'son of Man' (in Hebrew 'Ben-Adam ', in Aramaic, 'Bar-Adam'), thus 'son of God'. And, above all, it adds names, for instance, twice it adds Levis, and six times versions of the name 'Matthew' which are, interestingly enough omitted in the version given by Matthew the Levite, beyond its one 'Matthan' who is Joseph's grandfather. Ruth figures in the ancestry of David and of Jesus. We read these genealogies of Jesus given by Matthew and by Luke - and they tend to rather bore us, like Homer's endless catalogue of ships - and we fail to notice an important Levitical relationship. The genealogies set out to prove Jesus' descent from King David but not overtly or directly a relationship with Aaron the High Priest. However, that relationship does exist.

In Exodus 6.16-25 we learnt of Aaron's genealogy. Levi has three sons, Gershon, Kohath and Merari, of whom Kohath has four sons, Amram, Izhar, Hebron and Uzziel, of whom Amram marries Jochebed, his father's sister, who have Aaron and Moses, then Aaron marries Elisheba (Elizabeth), who is the daughter of Amminadab and the sister of Nahshon, their children including Eleazer, who in turn has a son, Phineas, these all being heads of the ancestral houses of the Levites. Now Jesus' genealogy in Matthew (1.2) again includes three of these names, 'Aram the father of Aminadab, Aminadab the father of Nahshon,' and so also does Luke (3.32-3) give 'son of Nahshon, son of Amminadab, son of Admin, son of Arni' (in manuscript variants, 'Aram' being included either before Admin or Arni in the series). Thus the Gospel compilers were aware that Jesus' ancestral stock had married into that of Aaron the High Priest through Elisheba, as well as including King David. John is priestly, like his mother and father, but Jesus is lay, though with a priestly cousin.

Astonishingly, the group which first acknowledges the adult Jesus as Son of David and as the Christ, the Messiah, is precisely that group indicated in the Magnificat and in the Beatitudes as those who are outside of worldly power and might. The lunatic, the man with the Levitically unclean spirit, in the Synagogue (lepers and the possessed had a special railed-off section of the Synagogue for their use, they could not enter houses) of 4.34, says, 'What have you to do with us? I know who you are, the holy one of God'. Then that evening crowds come to be healed, some likewise with demons who shout, 'You are the son of God' (4.41). And Jesus rebukes them, telling them not to speak, because they know him to be the Messiah. Next, in 8.28, the Gergesene demoniac who lives amongst the tombs, which in itself made one Levitically unclean, and who is possessed by a [Roman?] Legion which will next inhabit unclean swine (reminding one of the Prodigal Son), proclaims, 'What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the most high God'. Finally, the blind beggar (named Bartimaeus in Mark 10.46-52) outside Jericho keeps crying out in 18.38, 'Jesus, son of David, have mercy on me'.

Jesus himself, before his Resurrection, does not proclaim his Messiahhood; apart from his reading of the Isaiah passage in Nazareth's Synagogue. But he does propose a Rabbinical problem where he asks the crowd, which includes the Sadducees and Scribes of the Temple as well as his own disciples, how it could be said that the Messiah, the Christ, would be the son of David, since David says in the Book of Psalms, 'The Lord said to my Lord, sit at my right hand, and I will make your enemies your footstool', repeating again that if 'David calls him Lord how can he be his son?' (20.41-44, Psalm 110; and see Acts 7.55, Stephen's vision at his stoning). Jesus is well known to be a son of David, even by tax-gatherers, for that was why he was born in Bethlehem. His challenging Rabbinical question demands thought from his mixed audience. We recall his Passover question(s) at twelve in the Temple. And this will continue to be his strategy when he is brought before various illegitimate tribunals, to reflect back to his accusers their accusations as questions or to be silent, - rather than to nail their suspicions and fears, assertions and beliefs.

And lastly, in a crescendo of speed, it is the villains of the story, those who have power and who are unjustly abusing it, who keep questioning him, the Council asking, 'If you are the Messiah, tell us' (22.67), and 'Are you the son of God?' (69), Pilate, hearing that he has called himself Christ the King, asking 'Are you the king of the Jews?' (23.3), Herod, hearing this charge, even dressing Christ appropriately in one of his royal robes (23.11), the leaders of the crowd when Christ is on the cross saying 'He saved others. Let him save himself, if he is the Messiah of God, his chosen one' (23.35), and the soldiers profering him vinegar saying, 'If you are the king of the Jews, save yourself' (23.37), the authorities then placing the placard upon the cross ''This is the King of the Jews'' (23.38), the criminal hanging on the cross to his left demanding, 'Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!' (23.39), a demand we today can still phrase.

While of his disciples we only hear Peter saying that he is 'The Anointed of God', (9.20), calling into question the company Peter (and Christ) keeps. During his lifetime Christ may not call himself Messiah; just as Saints may not proclaim themselves Saints. But at his Resurrection, on the road to Emmaus, he can do so in response to Cleopas and the other disciple chatting about the women's 'kyrygma' (24.25-27), and again to the assembled disciples in Jerusalem (44-48), telling them on both occasions that the Christ must suffer, (24.26,46).

Which will bring us in the conclusion of this paper

as to who it was who anointed Jesus the Christ, the Messiah,

who administered the fourth sacrament? Was it a Levitically

clean male celibate priest as it should have been. Or was it

someone diametrically opposite to that status?

II. The Gospel within the Gospel

ur Anglo-Saxon word 'Gospel', 'God's Spell',

'God's Word', though archaic, is a strangely lovely word

with which to translate the Greek 'evangelion'. 'Gospel'

means in modern English 'Good tidings, the message, the

pronouncement, the proclamation of good news', such as those

proclaimed by Gabriel to Zachariah (1.11-20), by Gabriel to

Mary (1.26-38), and by Gabriel to the shepherds (2.8-15),

the word 'angel' in Greek meaning 'messenger'. In the three

messages concerning the two children, words become flesh,

the first concerns the first child who grows up to become,

in turn, the herald, the messenger, of the second.

Christ's ministry commences in the Synagogue in Nazareth , having prepared himself with baptism by John in the waters of the Jordan, and with forty days of fasting, prayer and withstanding temptation. He stands up to be recognised, the attendant hands him the Torah roll, specifically the roll of Isaiah, to read, and he seeks a particular, Messianic passage, self-referentially proclaiming it (Isaiah 61.1-2, Luke 4.18-19).

'The spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good tidings to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives and sight to the blind, to free the oppressed, to proclaim the Jubilee of the Lord'.

However, when we next hear the word 'aikmalotois'

that had been used in this passage from Isaiah in Luke for the

freeing of 'captives', 'kyrusai aikmalotois aphesin', it is in

its Jerusalem context as 'taken away as captives',

'aikmalotusthysontai' (21.24, and what could be more

oppressing than this grammatical future passive form of the

word?), where his Gospel is no longer of glad tidings of peace

but instead of warnings of war, when the inhabitants of

Jerusalem, as they were to do in A.D. 70, would meet with

devastating destruction. Yet those who were to carry away with

them this Gospel would eventually, with Constantine in A.D.

313, conquer their conquerors, and would have fulfilled these

prophecies not only of Christ but of Isaiah.

III. The Sacraments within the Gospel

A. The Water of Baptism

uke's Gospel began with the gestation and births

of the two cousins, one priestly, one kingly, the

descendants of Aaron and of David, John and Jesus. In

3.1-22, Luke presents John's ministry of baptism, based upon

Isaiah, to whom Jesus comes. John's most simple sacrament

requires first the admission that one is the outsider from

God and his Kingdom, needing to be cleansed to enter God's

presence, to become God's heirs. When people believe that

John is the Messiah (3.15), he answers that he baptises with

water, but that one will come who can baptise with the

spirit and with fire. Jesus then comes to be baptised by

him, that baptism of water being affirmed by the Holy Spirit

in the likeness of a dove descending upon him, and God's

voice saying, 'You are my Son, the beloved one, in whom I am

well pleased' (3.22). We shall next hear God's voice at the

Transfiguration with Jesus seen between Moses and Elijah

on Mount Tabor , 'This is

my Son, the chosen one, hear him' (9.35). Though it is

absent on Gethsemane and Calvary.

We next hear of water in the scene (in Luke in the Galilee region though in the other three Gospels later and in the Jerusalem and Bethany areas), where a woman comes to Jesus as he reclines at a dinner given by a Pharisee and where she weeps tears upon his feet and dries them with her hair, kissing them, and also anoints them with oil (7.37-38), thereby using not one but two of the sacramental substances. His host Simon is disturbed that he allows this unclean woman to touch him. But Jesus answers, 'I entered your house but you did not give me water for my feet . . . you did not give me a kiss . . . you did not anoint my head with oil' (7.44-46), while the repentant woman of ill repute has not left off washing his feet with her tears and drying them with her hair, covering them with kisses and anointing them with oil. In the next section of verses we hear more of such Galilean women who would accompany Jesus even to his Crucifixion in Jerusalem, even that one is Mary of Magdala from whom Jesus cast out seven demons (8.2), and that another is Herod's steward's wife Joanna, and another a Susanna. Women prophesied Christ's Messiahhood equally with men and his ministry continued to include them, Mary, Jesus' mother, and the other women from Galilee, in Acts 1.14, being present with the disciples in prayer, and likely at the election for Judas' replacement and at Pentecost. Nor should Mary Magdalen's presence really shock Jews or Christians, for was not David descended not only from Gentile Ruth, but also from adulterous Bathsheba, and even from Rahab the harlot?

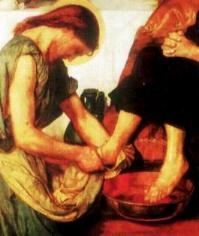

That action of washing was essential in Judaism; one could not touch an unclean woman or the dead without washing oneself and undergoing purification. Here, the paradox is that it is the unclean woman who touches and washes and anoints the priestly man, consecrating him as Messiah, as Christ. In Mark and in Matthew Jesus proclaims of the similar anointing by Mary at Bethany 'Truly, I say to you, that wherever the Gospel is preached in the whole world, what she has done will also be told in remembrance of her,' (Mark 14.9, Matthew 26.13; John 12.1-11 giving the same story but as being the cause for Judas' betrayal of Christ from envy). These words are hauntingly similar to those of the institution of the Eucharist, 'do this in memory of me' (22.19). Later, though not in this Gospel, we shall witness Jesus stooping to copy this act, in his washing of the feet of his disciples at the Passover 'seder', his institution of the Eucharist, teaching them that it is crucial to serve and be lowly; while they wrangle as to who is the greatest (22.24-27, repeating the earlier 9.46). It was essential to wash one's hands before a meal; Jesus insists on washing the lowest part of his disciples, as had the repentant Galilean woman of ill repute insisted upon washing his feet (which later these women would see pierced with nails), instituting in memory of both these events a sacrament. We remember John the Baptist saying that he was unworthy to undo the strap of Jesus' sandal (3.16), to signify his comparative lowliness.

[I lack information on the source for this painting. It is so clearly a detail from an English Pre-Raphaelite one, unless it is of the German Nazareth School. It came to me as a card inviting people to a diaconal ordination in Fiesole's Cathedral, one of the deacons so ordained, now don Bernardo Ravano, C.F.D. and Priest. Again, as in Sacred Conversation: Contemplating a Painting , place yourself in this painting, feel your feet being washed by the Lord, you who are His Disciple, his Servant, and likewise, as one of the Holy Women, 'hold him by his feet', - and feel them in your hands. One Godfriend tells me she has it on the cover from a book on the Amish and that it is in the Tate Gallery, London.]

The early Church would have bishops and deacons (a word meaning servant), but not priests, celebrate the Eucharist. Medieval kings and queens and Benedictine abbots and abbesses, such as St Hilda of Whitby, would so wash their subjects', guests', brothers' and sisters' feet.

All these actions are about humility without which there cannot be 'metanoia'. That brings us to the parable of 'Dives and Lazarus', as it is titled in Wyclifite works from the Roman stock dramatic character of the wealthy man as 'Dives', like the typical soldier as 'Miles', though we know from the Bodmer papyrus that its rich man's name was more likely 'Nineveh'. A poor man, whose name echoes that of the brother to Mary and Martha, and of the priestly Eliezers, is thrown down, filled with sores, by a rich man's gate. Like the Prodigal Son (15.16-17) and the Sidonian mother (Matthew 15.21-28), he longs for the crumbs that drop from the rich man's table. When Dives and Lazarus die they exchange places, Lazarus lying in Abraham's lap, Dives/Neuys roasting in Hell. Looking up across the abyss he begs Abraham to send Lazarus down to him, that Lazarus might dip 'bapsys', the tip of his finger in water and cool his tongue for him from the flames's heat (16.24). Abraham replies that he cannot so help his child, or his rich brothers, who would pay no heed to the Law or even to a Lazarus or a Christ raised from the dead. That appellant 'child of Abraham', (24-25) looks ahead to the abhorred Jewish tax collector Zacchaeus in Jericho, similarly called 'son of Abraham', but who does repent while living (19.9). One remembers the medieval legends generated from Whitby and in Bede, then in Dante, Langland and the Pearl Poet, of Gregory weeping for the corpse of the pagan Emperor Trajan and of St. Erkenwald weeping over the corpse of the pagan just Judge, whose tears baptise the pagan souls, saving them.

Luke notes of John the Baptist that the Pharisees

and Scribes rejected his baptism, and by rejecting that

baptism, they rejected God's purpose for themselves (7.30).

The waters of baptism and the tears of repentance are not

costly in the world's terms as were the Temple's sacrifices

for attaining Levitical cleanliness. But they are the payment

for the pearl of the greatest price, of the Kingdom of God.

Isak Dinesen, herself afflicted by syphilis contracted from

her lawfully wedded husband, wrote that 'Pearls are like

poets' tales; loveliness born out of disease'. Alcoholics Anonymous' ministry is

probably the closest we have today to the Gospels' 'Good

News'.

B. The Wine of Marriage

uke does not tell us of the miracle of water

turned into wine at the marriage feast at Cana (that is in

John 2.1), though Luke does give us similar episodes where

Jesus rebuffs members of his own family (3.49, 8.19-21;

Thomas' Gospel 97.21-26). Nevertheless, let us take wine as

symbol of the wedding feast in Luke's Gospel, signifying the

joy between bridegroom and bride, between Judaism and

Jerusalem, between Jews and the Sabbath, between the Messiah

and Israel. In these examples and parables we shall also

find it to signify separation, divorce, rejection and

tragedy. Jesus himself was born into a household in which

divorce threatened, Matthew telling us that Joseph, being a

righteous man and finding Mary pregnant, 'wished to divorce

her quietly' (1.19), before the child's birth; during that

period, Luke tells us, when she took refuge with her

priestly cousin, Elizabeth, during the last three months of

Elizabeth's pregnancy, the first three of her own. It was at

that Visitation that

Mary joyfully proclaimed her 'Magnificat'. As an adult,

Jesus spoke sternly against divorce (16.18), even though

that word in Greek, 'apoluo', more typically means 'release,

set free, send away, send off,' and even 'forgive', while he

defended the woman taken in adultery. Incidentally his

writing in the dust in John 8.6 may be related to the Jewish

trial for adultery at which a woman drank the bitter waters

made from Temple dust and unclean water used to wash the

writing the priest wrote out for her in ink from Numbers

5.19-22. She was very rarely put to death.

uke does not tell us of the miracle of water

turned into wine at the marriage feast at Cana (that is in

John 2.1), though Luke does give us similar episodes where

Jesus rebuffs members of his own family (3.49, 8.19-21;

Thomas' Gospel 97.21-26). Nevertheless, let us take wine as

symbol of the wedding feast in Luke's Gospel, signifying the

joy between bridegroom and bride, between Judaism and

Jerusalem, between Jews and the Sabbath, between the Messiah

and Israel. In these examples and parables we shall also

find it to signify separation, divorce, rejection and

tragedy. Jesus himself was born into a household in which

divorce threatened, Matthew telling us that Joseph, being a

righteous man and finding Mary pregnant, 'wished to divorce

her quietly' (1.19), before the child's birth; during that

period, Luke tells us, when she took refuge with her

priestly cousin, Elizabeth, during the last three months of

Elizabeth's pregnancy, the first three of her own. It was at

that Visitation that

Mary joyfully proclaimed her 'Magnificat'. As an adult,

Jesus spoke sternly against divorce (16.18), even though

that word in Greek, 'apoluo', more typically means 'release,

set free, send away, send off,' and even 'forgive', while he

defended the woman taken in adultery. Incidentally his

writing in the dust in John 8.6 may be related to the Jewish

trial for adultery at which a woman drank the bitter waters

made from Temple dust and unclean water used to wash the

writing the priest wrote out for her in ink from Numbers

5.19-22. She was very rarely put to death.

In Luke 5.33, Jesus is challenged for not praying or fasting and instead for eating and for drinking wine, unlike the disciples of John the Baptist or the Pharisees. He replies to his critics, 'Can you make the bridegroom's guests fast while he is with them? But the days will come when the bridegroom is taken from them, and then they will fast in those days' (34-35; Thomas' Gospel 98.11-16). Then he tells the parable of new wine in old wineskins (37-39; Thomas' Gospel 89.17-22).

A most moving parable, unique to Luke, is that of the Good Samaritan who finds a traveller on the Jericho road who has been beaten, robbed and left for dead and whom a Priest and a Levite have passed by. The Samaritan binds his wounds, after anointing them with antiseptic wine, 'oinon', and healing oil, 'elaion', then places him on his own beast to take him to an inn (10.30-35). The tale is told in answer to a scribe who had wished to fulfil the Law but questioned who was his neighbour whom he must love as himself. Patristic and medieval exegetes who read the parable as of Fallen Mankind, beset by the Devil, unaided by the Priest (Abraham) and the Levite (Moses) of the Old Law, though saved by the Christ of the New Covenant, were not far from its meaning. It is a parable against the priestly caste that was not healing sick Israel. In place of the Temple sacrifices it gives simple and available sacraments, wine and oil, administered by the laity, even by the outsider, by the hated Samaritan, by the almost Gentile.

In the Gospels there is a crescendoing of parables of lords and stewards, of lords and tenants, of vineyards and of their stewardship, building upon those of the Hebrew Scriptures, for instance as in Psalm 80.8-16 and in Isaiah 5. In Luke 20.9-19's Parable of the Vineyard and the Tenants we are very much in the Mediterranean world in which landlords expect tenant farmers, 'georgoi', to share their produce with them. Alas, tax-farming also enters here, where an agricultural image served for a commercial one. It was by such means that vineyards produced the grapes that became the wine of Passover and Wedding feasts, and by such means that Caesar, Herod and the High Priests Annas (in office, A.D. 7-13) and Caiaphas, his son-in-law, (in office, A.D. 18-36) gained their wealth and power. Yet Luke's Parable of the Vineyard and the Tenants is clearly recognised by the Scribes and chief Priests as being told on another level and as against themselves (20.19). It is this parable, in which finally the Lord of the Vineyard sends his only and beloved son and heir, who is promptly murdered by the tenants, which provides the beginning of the Epistle to the Hebrews and its concept of God's heir as Christ, (20.14, Hebrews 1.2). Traditionally, Christians read these Parables as being against the Jews, with disastrous consequences for both Christians and Jews. In reality, Jesus was speaking out against not Jews but the powerful and wealthy elite of the Priests and Scribes. And what he said was fulfilled, it being the Priests and Scribes who arranged for his Betrayal and Crucifixion, while the Jewish people mourned him (23.48).

It is not generally recognised that the phrase used twice in Luke, 'Blessed is he who comes in the name of the LORD,' (13.35, 19.38), taken from Psalm 118.26, which we have embedded in the Eucharist, is to this day used at a Jewish wedding to greet its bridegroom. Similarly had the chapter in Isaiah which Jesus had read at Nazareth , concluded with bridal imagery: 'I will greatly rejoice in the LORD, my whole being shall exult in my God; for he has clothed me with the garments of salvation, he has covered me with the robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom decks himself with a garland, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels' (Isaiah 61.10-11). Palm Sunday is as a wedding procession.

Next, at the Passover feast in the Upper Room, and it clearly is the Passover feast in Luke, while Jesus and his disciples are reclining as he earlier had in the Pharisee's house, he receives the cup, blesses it, and tells his disciples to share it, (22.17), adding that he will not drink of the fruit of the vine again until he has come into the Kingdom of God, ' (22.18); then, again he takes the cup, following the blessing and eating of the bread, (23.20), proclaiming the cup to be the new covenant poured out in his blood, this time the cup being the 'seder''s 'cup of blessing'. We have earlier heard Jesus disputing with the Pharisees among other topics the cleanliness of cups' (11.39; Thomas' Gospel 83.24-27 & 96.13-16). In Judaism it is the dead and blood which defiles. Jesus involutes, in the Eucharist, all that is most sacred and most profane in Judaism.

Later, on the Mount of Olives, to which Jesus and

the disciples have passed, taking the arched bridge above all

the white-washed tombs of the dead lying beneath them in the

Kidron Valley, Jesus prays to God, 'Father, if you wished, you

could take this cup from me, but nevertheless not my will but

yours be done' (22.42). Then, on the cross, he is mockingly

given vinegar to drink by the soldiers (23.36), and this just

after he has, in manuscript variants, asked God's forgiveness

for them. In flesh and blood and bread and wine he passively

enacts his own Parable of the Vineyard and the Tenants, as his

Temple's Priesthood betrays and murders the spouse's

bridegroom, turning his wine into vinegar and gall, his life

into death.

C. The Bread of Communion

ary in the Magnificat declares that the Lord fills

the hungry with good things, but sends the rich away empty

(1.53). Then her child is born in royal David's city, Bethlehem , which means

in Hebrew 'Beth', 'house',

'Lehem', 'of bread', and was even laid in the manger, in

place of the grain normally given for feed to the ox and ass

(interpreted in the Fathers as Jews and Gentiles), as if for

our sustenance. John the Baptist announced to his followers

that the Messiah would come with his winnowing fan in his

hand to clear his thrashing floor and gather the wheat into

his barn, burning the chaff in unquenchable fire (3.17;

Thomas' Gospel 90.33-91.7). When Jesus is fasting and

praying for forty days and nights in the Jericho Wilderness

the devil tempts him saying that if he were the Son of God

he could make stones into bread (4.3). Jesus in reply quotes

Deuteronomy 8.3, 'It is written that man shall not live by

bread alone' (4.4. That passage speaks of God feeding the

Israelites in the Wilderness with manna when they lack bread

while warning them that they are not to be fed by bread

alone but by every word of God). Later, Jesus will give the

Parable of the Sower, which interlaces with John's Parable

of the Harvest and to Deuteronomy's verse (8.4-15; Thomas'

Gospel 82.1-13). And he will say of those who would follow

that once they have put their hand to the plough, if they

desire the Kingdom of God, they must not look back (9.62).

When Jesus begins his ministry in the Synagogue at Nazareth he speaks of Elijah aiding a widow in Sidon, rather than the multitude in Israel, in time of famine (4.25-26). Then, when Jesus and his disciples on a Sabbath eat the grain, husking the plucked wheat ears in the field within their hands, the Pharisees object. Jesus replies to them with the story of David and his men eating the bread in the Temple, which was not lawful to eat except by priests (6.3, 1 Samuel 21.1-6). It is of interest that while other Gospelers have the disciples of Jesus address him as 'Rabbi', Luke never does so, perhaps because of its Pharisaical overtones. Yet Luke's Jesus makes great use of Rabbinical learning.)

In Luke 6.20, Jesus very clearly addresses the Beatitudes to his disciples, though he speaks the words to all present, 'And he raised his eyes to his disciples saying, 'Blessed are you for being poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God'. Those words 'Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God' are a necessary corrective to the self-serving privileges and wealth of the Priests and Scribes. He applies them both to his disciples and to his audience. He next gives that verse that had also been his mother's in the Magnificat, 'Blessed are you who hunger now, for you shall be filled' (6.21; Thomas' Gospel 93.28-29). He then addresses those who having the kingdom of the earth now shall not inherit the Kingdom of Heaven, 'But woe to you who are rich, for you have had your consolation, woe to you who are satisfied now, for you will hunger' (6.20-25).

He significantly addresses those words to his disciples, first the twelve, then the seventy or seventy-two, whom he will send out to preach concerning the Kingdom of God and to heal, with nothing for their journey, neither staff, nor bag, nor bread, nor money, nor extra clothing, nor sandals (9.3), and (10.4), discussed again by Jesus, 22.35. Alfred Edersheim, The Temple: Its Ministry and Service at the Time of Jesus Christ, notes that here Jesus makes his disciples behave in the world in the way Jewish pilgrims were required to be in the Temple, without staff, or bag, or extra clothing, or shoes, or bread, or money, except what they held in their hand to pay for the sacrifices. Which is why the Pharisee who, in the Temple, produced a Roman denarius from his purse engraved with Caesar's image and inscription, (20.24; Thomas' Gospel 97.27-31), was breaking innumerable God-given Jewish laws. Jesus' Apostolate is commanded to function as if in the sacred Temple while abroad in the world. Nor are his disciples to behave like the Temple's priests, but instead like Hebrew pilgrims; they are to be the laity, they are to have no privileges.

Then we have Jesus feeding five thousand men and their unnumbered women and children from only five loaves of bread and two fishes, the crumbs left over filling twelve baskets (9.13-17). At Tabgha today where this miracle took place one can see the early Christian mosaic floor of the loaves as communion wafers with crosses upon them in baskets flanked by two St. Peter's fish, delicious but boney fish which are only to be found in the Sea of Galilee, beneath the altar. Then, when he teaches them to pray the Lord's Prayer, with its line, 'Keep giving us every day our needed bread', (11.3), he concludes with the Parable of the man asking a friend, who rejects his request because his household is asleep, for three loaves of bread to feed an unexpected guest (11.5-8). That line in the Lord's Prayer recalls for the worshiping Christian not only the daily bread sustaining the body, but also the Eucharist of bread and wine sustaining the soul. Indeed, in the Gospel context and in the contexts of modern liberationist theology, one hears that line polyphonally, as in the Latin American grace, 'O God, to those who have hunger give bread and to us who have bread give the hunger for justice', even to rephrasing the Lord's Prayer as 'Give to us each day our daily bread as we give bread to those who hunger'. Do you give your child, when he asks for bread, a stone, or when he asks for fish, a serpent?

God established the Feast of Unleavened Bread, for

Israelites in the Month of the Corn, the month of Abib, in

memory of the Passover and the manna of the Wilderness. All of

these harvest metaphors and parables and miracles concerning

bread, each of which is related to the Kingdom of God within

us, culminate in the Passover Supper in the Upper Room, where

between the sharing of the wine, Jesus takes what would at

this Passovertide be unleavened bread and, having given

thanks, he breaks it and gives it to his disciples, saying,

'This is my body which is given to you. Do this in remembrance

of me,' (22.19). Then, though this is called the Last Supper

(it could better be called the First Supper), we next find

Cleopas and another disciple at an inn at Emmaus on Easter

Monday with an unrecognised third pilgrim who speaks of the

Messiah and then, at their supper, takes bread, blesses and

breaks it and gives it to them, before he disappears (24.30).

The next time he eats with his disciples in Luke it will be

not bread, but fish, (Galilean St. Peter's Fish?) and in some

manuscript variants, honeycomb, John the Baptist's food. He

has memorialised his presence on earth, his flesh and his

blood, in the everyday bread of the Lord's Prayer and the wine

without which a Mediterranean meal would not be complete. For

century upon century water, wine and bread have been brought

to the Communion Table in his memory.

D. The Oil of Anointing

Catholic child is baptised with water, salt and

olive oil. An Anglican child was generally baptised just

with water. Perhaps at Confirmation the Bishop may now sign

the candidates' foreheads with the cross in holy oil. Kings,

Queens, Priests and Deacons are anointed, but for the laity,

until recently, there was only and rarely Extreme Unction at

approaching death. Today, though there is a return to more

use of the oil of anointing for the laity, we have largely

lost this major sacrament in the Church of England

specifically and in Protestantism generally. Once it was

what made us 'Christian', meaning 'anointed', as does the

epithet 'Christ' which we use of Jesus. We are in his image.

Therefore his anointing should be ours also. Jesus' 'Gospel'

is that all are the Messiah, that Israel cannot be conquered

and destroyed by Rome, but will convert the whole world to

God. Perhaps, in this 'Decade of Evangelism', we should

reform our Church as once again truly 'Christian', as truly

consecrated, as truly of the anointed. It could be as

simple, as peaceable and as universal an action as were

Gandhi's non-violent strategies (borrowed in part from

Tolstoy's 'The Kingdom of God is Within You' and from

Thoreau's 'Civil Disobedience') for the freeing of India,

that were adopted next by Martin Luther King in America and

whose fruit we see today in Russia and other former Iron

Curtain countries, and in strife-torn South Africa, Israel

and Ireland.

Catholic child is baptised with water, salt and

olive oil. An Anglican child was generally baptised just

with water. Perhaps at Confirmation the Bishop may now sign

the candidates' foreheads with the cross in holy oil. Kings,

Queens, Priests and Deacons are anointed, but for the laity,

until recently, there was only and rarely Extreme Unction at

approaching death. Today, though there is a return to more

use of the oil of anointing for the laity, we have largely

lost this major sacrament in the Church of England

specifically and in Protestantism generally. Once it was

what made us 'Christian', meaning 'anointed', as does the

epithet 'Christ' which we use of Jesus. We are in his image.

Therefore his anointing should be ours also. Jesus' 'Gospel'

is that all are the Messiah, that Israel cannot be conquered

and destroyed by Rome, but will convert the whole world to

God. Perhaps, in this 'Decade of Evangelism', we should

reform our Church as once again truly 'Christian', as truly

consecrated, as truly of the anointed. It could be as

simple, as peaceable and as universal an action as were

Gandhi's non-violent strategies (borrowed in part from

Tolstoy's 'The Kingdom of God is Within You' and from

Thoreau's 'Civil Disobedience') for the freeing of India,

that were adopted next by Martin Luther King in America and

whose fruit we see today in Russia and other former Iron

Curtain countries, and in strife-torn South Africa, Israel

and Ireland.

Let us go through Luke's Gospel once again, this time tracing not the water of baptism, the wine of marriage and the bread of communion, but the olive oil of the anointing.

In Zachariah's Benedictus or Blessing, Aaron's oil for the anointing of priests and the house of David come together splendidly in one verse, 'He has raised up for us a horn of salvation in the house of his servant David' (1.69), the priest with his words anointing the child still to be born, a king, as had Samuel anointed David, as is even our Queen anointed at her coronation in Westminster Abbey. Zachariah adds that through this Saviour, this Messiah, the nation of Israel will be consecrated and righteous before God' (1.75). When the angels tell the shepherds of the birth of the child, they announce, 'that to you this day is born a saviour who is Anointed Lord, in the city of David' (2.11). When Zachariah's son, John the Baptist, heralds Christ as baptising not with water but with the Holy Spirit and flame, he had just been asked if he were not himself the Christ, the Messiah, the Christ, the Anointed (3.15). Then, when Jesus reads the passage from Isaiah in the Synagogue at Nazareth he reads and applies to himself the words, 'The spirit of the Lord is upon me and he has anointed me to bring the Gospel to the poor' (4.18). And his audience, his congregation in the Synagogue, would also know that those verses go on to speak further of the oil of the anointing, of 'the oil of gladness instead of mourning' (61.3). This is Jesus' most overt 'kyrygma' in Luke, during his lifetime, announcing himself as Messiah. He immediately learns not to do so, barely escaping with his life from the crowd at Nazareth.

The reading of Isaiah 61.1, has been a verbal proclamation, a speech act, concerning the Messianic anointing, linking the similarly named Isaiah, 'Yeshaiah', and Jesus, 'Yeshua'. But nowhere do we hear of the physical act of anointing though often we hear of Jesus as called the Christ, the Anointed One. Except in the story of the sinful woman who gate-crashed Simon the Pharisee's dinner party and who washed Christ's feet with her tears, dried them with her hair, and kept kissing them and anointing them from an alabaster jar of myrrh (7.38). Christ then turned to Simon and said among other things that he had not anointed his head with oil but that she was anointing his feet with myrrh, (7.46). The oil for the anointing of priests and kings and guests and recovered lepers and the dead was concocted from olive oil mixed with myrrh and other precious spices (Exodus 22-33, Psalm 133). And it is following this episode that we have Peter blurt out that Jesus is the Anointed of God (9.20).

On the way to Jerusalem while traveling on the border of Samaria with Galilee Jesus is met by a group of ten lepers. He tells them they are to show themselves to the priest. One turns back on finding himself cleansed and healed and praising God, thanks Jesus, who asks where the other nine are. Jesus then tells this one leper, who is a Samaritan, that his faith has healed him' (17.11-19). Edersheim gives a careful account of the ritual for the cleansing of lepers; which concludes with the anointing with oil. In this instance, the tenth leper has not needed that Temple cleansing, his belief in the Christ being sufficient.

Then, we have Jesus customarily spend his nights on the Mount of Olives , to which he and his disciples go, even following the 'Last' Supper (22.39). To cross from Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives they have to pass over the defiling, polluting tombs of the Jewish dead that lie everywhere in the ravine of Kidron, which have been carefully white-washed to prevent such danger a month prior to Passover. When next we hear of anointing it is again by women but this time it does not happen. The women who had followed him from Galilee at early dawn bring the spices they had prepared to anoint his body but it is gone from the tomb. Mary Magdalen and Joanna, Herod's steward's wife, and the others tell the disciples of finding the tomb empty and of the angels, the disciples considering these things but an idle tale, until Peter checks into the story himself (23.56- 24.1-12,22-24).

In Hebrew, Jesus is spoken of as the Messiah, which in the Greek Gospels becomes 'Christos', both words meaning the 'Anointed One'. In the Gospels his anointing is not a priestly one by a male, but a lay anointing by a woman. While in the parable in the Gospel the anointing with oil and wine of the wounded traveler was effected neither by the priest nor the Levite but by the outsider, the almost Gentile, the Samaritan. Indeed there is a Messianic vocabulary in the Greek Testament, a clustering of words, of healing, of mercy, of coming, of freedom. And the word 'anointed', reflects as well, 'kind, loving, good, merciful'. Similarly, in Hebrew, there are echoes between the names of Joshua, 'Yehoshua,' Isaiah, 'Yeshaiah,' and Jesus, 'Yeshua,' and the words for salvation, deliverance, help, and related words, used of the Hasidim, for instance, of goodness, kindness, mercifulness, grace. Jesus Christ in his names, his words, and his deeds extended the franchise of holiness, of the royal priesthood, to all who believed on him, children, slaves, women, men, tax-collectors, lepers, paralytics, lunatics, beggars, the lame, the blind, the deaf , proclaiming, 'Whoever receives a child in my name, receives me, and whoever receives me receives the one who sent me' (Luke 9.48). Jesus told women and men that their faith had saved them, as in the double miracle (and double pollution) of Jairus' twelve-year-old daughter raised from the dead and the woman who had been haemorrhaging for twelve years to whom Jesus says, 'Daughter, your faith has saved you; go in peace' (8.48), and likewise to the Samaritan leper and to the thief on the cross at his right hand, implying again and again to unclean and criminal lay women and men that they had returned, through their faith and 'metanoia', as were also children in their innocence, to being in his image who had created them, that they were saved and healed, their sins forgiven them, that they had entered the Kingdom of God. He promulgates not a religion of Pharisaic separatedness, but one of global inclusion.

In the Gospels there is a splendid symmetry between the four sacraments of water, bread, wine and oil. The first, of water, is begun by John. Jesus administers those of bread and wine. But it is a woman who administers the oil of the anointing, along with the water of her tears, in true 'metanoia'. In Christianity, Christians, women and men, follow Christ, becoming in his image, first with the cleansing from sin through baptism by water, then with the consecration into holiness through the anointing with oil, and next to be sustained with the bread and wine of the Eucharist. The sacrament that once made Christians most truly 'Christian' in the early Church was decidedly that carried out with the oil of the anointing. Gregory Dix's The Shape of the Liturgy traces the Early Church's continuation of these Gospel concepts, derived from Jewish liturgical practices, until the centrality of the Bishop, representing the anointed Christ with the power to anoint all Christians, and served by Deacons for men, Deaconesses for women, in this task, became lost with the introduction of Priests taking over the Bishop's and Deacons' and Deaconesses', roles as Consecrators, Servers and Baptisers. In so doing Christianity became again Levitical and Pharisaic. Gerald Vann in The Divine Pity quoted St. Ambrose, 'We are all anointed into one holy priesthood', and discussed at length the common priesthood of the laity in which we all share. The High Priest Jesus inaugurates the possibility that all humankind may be of the Royal Priesthood, in his image, who created us and who atoned, 'at oned' , for us, 'noughting' our sins.

Epilogue

n Exodus 19.4-6, God had spoken magnificently to

Moses, saying, 'Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob,

and tell the Israelites: You have seen what I did to the

Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought

you to myself. Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep

my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all

peoples, Indeed the whole earth is mine, but you shall be to

me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. These are the

words that you shall speak to the Israelites'.

n Exodus 19.4-6, God had spoken magnificently to

Moses, saying, 'Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob,

and tell the Israelites: You have seen what I did to the

Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought

you to myself. Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep

my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all

peoples, Indeed the whole earth is mine, but you shall be to

me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. These are the

words that you shall speak to the Israelites'.

That dream of a people as a Royal Priesthood, by Jesus' day, with the Herodian Temple and Roman hegemony, had become a nightmare in which its priestly caste, as shown especially in Luke's Gospel, colluded with Israel's Roman invaders and conquerors, imposing upon Jews a double burden of taxation, to Caesar and to God, and a double religio-legal system, Rome's and Israel's. Elizabeth and Zachariah, as members of the priestly caste, are exempt from the payment of John's redemption, but not Mary and Joseph from the payment of Jesus', because they are lay persons. Edersheim has calculated the taxes paid to the Temple by devout Jews were not a tithe, a tenth, but a quarter of their whole wealth, their whole living, on top of which they had to pay taxes to Rome. Elizabeth and Zachariah, because they were of the priesthood, were also exempted from the poll-tax, the crown-tax and the salt-tax to the secular Roman authorities, but not Mary and Joseph. Even the census promulgated by Caesar Augustus that brought Mary and Joseph from Nazareth to Bethlehem and caused them such hardship at Jesus' birth, treating them like animals, rather than as human beings, was for Roman taxation purposes (2.1-7).

Meanwhile, in Jesus' time, the High Priest was actually nominated by the King set in place by the Roman authorities, until quite recently the Hasmonaean Kings and High Priests having been one individual. The Priests and Scribes, who did not have to pay taxes to either Temple or Caesar, were then even further subsidised by Herod, to guarantee their support of Herod and Caesar. We witness next not only the unusual collusion between Pharisee and Sadducee against Christ; we also witness the enemies Herod and Pilate becoming friends over the same person and issue (23.12). Herod's Idumaean ancestry was not even genuinely Jewish. The mocking of Jesus by Herod may well be a mirroring back in play of Herod's own doubts about his own legitimacy. The false Priest King attempts to falsify and make counterfeit the true one in play and mock, (23.11).

A major cause for the heavy taxation was the building of the Herodian Temple, to replace that built by Jesus' ancestor, Zerubbabel (3.27). While some were praising the Temple for its beautiful stones and votive adornments, Jesus replied that, 'What you see in days to come will not be left standing with one stone upon another; all will be destroyed' (21.5-6). That prophecy was almost fulfilled in A.D. 70, by the Romans under the Emperor Titus. Nor was this the only reference Jesus and others made to the stones of the Temple, which were huge white blocks cut from the rock beneath Jerusalem, for we find Satan tempting Jesus with lines from Psalm 91.11-12 as he attempts to persuade him to a suicidal leap from the Temple's spur, that the angels will bear him in their hands lest he dash his foot against a stone, (4.11), following upon the temptation to turn stones to bread (4.3). Then, in response to the Pharisees' anger at his Parable of the Vineyard and Tenants, he quotes Isaiah 8.14-15, that the stone that the builders rejected will become the head of the cornerstone (Isaiah 8.14-15, Luke 20.17, Acts 4.11, 1 Peter 2.7, Thomas' Gospel 93.17-18, Barnabas' Epistle, pp. 130-131). He will exchange for a Temple of stone, a Temple of the body, of flesh and blood and breath. At the same time, he makes clear that the funding for the Temple of white stone is carried out through continuously devouring, the livelihood of widows (20.46-47-21.1-4). The Temple and its Priesthood are a stumbling block, a scandal, in Israel. It is not for Christendom.

First John, then Jesus, sought to reform Israel back to being a priestly people. John made it possible for such cleansing to take place without the blood sacrifices of bulls, goats, lambs and birds, of heave offerings and wave offerings, of sin and thank offerings, bought by money, but instead by the use of simple and free water, a cleansing accompanied by a change in the personality, a conversion, a 'metanoia', while he lived himself in the Wilderness in simplicity and poverty. Jesus added to John's use of water, other simple elements, available to any Mediterranean peasant, wine and bread. Mary (so named in the other Gospels, in Luke it being an unnamed woman), then came and added to these oil from the olive mixed with myrrh. John, Jesus and whoever Mary was made it possible for all Israelites;and later all Gentiles, to be a priestly people consecrated to God. They instituted a powerful Messianic reform of Judaism back to its earliest theocratic principles; which was resisted utterly by those who stood to lose from that reform, those who had gained privileges, wealth and power from the fear and corruption that conquest brings, such men as the privileged Priests and Scribes, and even from those normally opposed to them, the Pharisees, who, in this instance, colluded with them in plotting to destroy their critic and judge, Jesus. Scribes and Pharisees together shared religious power, arguing over the jots and tittles, of the Law, the Englished phrase recalling the 'yod ', the smallest letter in the Hebrew alphabet;and the one that begins Jesus' name; and the horns to the letters that help distinguish them one from the other, in other words, the fine print of a legal document (16.16-17, for example, the first being 'beth', a house, a tent, the second 'kaph', simply the palm of one's hand in which a -can be held, only the tittle really distinguishing them).

When Westcott used the phrase of Luke's Gospel, that it is the Gospel in which we see Christ in 'the image of our Great High Priest', he was quoting not from the Gospel of Luke but from the anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews, whose subject matter concerns Christ as Priest King. One clear relationship between the two texts may be seen in the Parable of the Vineyard, whose owner finally sends his only son and heir, who is then killed by the tenant farmers that they may win the inheritance (Luke 20.9-16, especially 13-14, Thomas' Gospel, 93.1-16), then continues by using the Psalm of David, 110.1, that Jesus had discussed, Luke 20.41-44, 'The Lord says to my Lord, Sit at my right hand'.

In the Gospel of Luke, in the Epistle to the Hebrews, and in the Epistle of Barnabas there is the demonstration, the argument, the thesis that the Levitical priesthood, of Moses and Aaron, has somehow failed Israel, as indeed had Aaron himself failed the Israelites with the shaping of the Golden Calf in Exodus. (Peter, with his very human fears [Luke 5.8], doubts [Matthew 14.22-33], and denial [Luke 22.54-62], of Christ, reenacts Aaron's betrayal of Moses [Exodus 32].) The Epistle to the Hebrews used Psalm 110.4,5's line, 'You are a priest for ever, after the order of Melchizedek', words vowed by God in the Psalm, allowing Hebrews 7.17 to stress instead the priesthood of the Gentile King and Priest of Salem, Melchizedek, rather than the Jewish priest, Aaron, partly because its author cannot find that Jesus, from the house of Judah, had any priestly associations (Hebrews 7.13-14), but more importantly because this was a priesthood of simplicity and generosity, a mystical priesthood of the sacraments of water, wine, bread and oil, rather than of blood sacrifices, of heave and wave offerings, of sin and thank offerings, of bulls, of lambs, of goats, of birds, which likely were pagan imports into Judaism and which are not now carried out save by Samaritans. It is as if the circle of Paul, if not Paul himself, with people such as Barnabas, Luke, and perhaps Apollos, are helping shape Judaism into Christianity. This mystical priesthood of Melchizedek in the realm of eternity rather than of time, and with the simplest sacraments, is one of peaceable inclusion, rather than of rigorous exclusion.

That the Epistle to the Hebrews, the Epistle of Barnabas and the Gospel of Luke are related to each other has been hinted at by many commentators, both early and late. They likely came from that circle about the converted Pharisee, Paul, which included Barnabas, John Mark, Timothy, Apollos, Prisca, Aquila and Luke. Some of the scholarship cites Apollos or Priscilla as likely the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews, or note Egyptian references ascribing it to Barnabas. The Epistle to the Hebrews was included in the canon, not so Barnabas' Epistle. Cyril, the Archbishop of Jerusalem, Jerusalem's Christian High Priest, made use of the Epistle to the Hebrews again and again in his 'Catechetical Lectures'. Moreover, it deeply imbedded itself in monastic liturgy, as can be seen in the Order of Tenebrae.

Related to both the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Epistle of Barnabas is also an Epistle written by Peter or an elder of Rome echoing God's words to Moses, 1 Peter 2.9, 'But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his possession, that you might proclaim his redemptive acts', which it embeds in the words from Isaiah Jesus spoke concerning the stone the builders rejected, a stumbling block, a scandal, but which became the head of the cornerstone of the new Temple (Isaiah 8.14-15, Luke 20.17). They would be picked up as well in Revelation 5.10, 'You have made them a kingdom and priests to God and they will rule on earth.' Israel had been conquered by Rome, but simple fishermen like Peter and Andrew, tax collectors like Matthew Levi (is he a tax collector for Rome or for Jerusalem, for Caesar or for the Temple?), even Pharisaic tent-makers like Paul, Prisca and Aquila would come to conquer their conquerors and by the time of Helena and Constantine the Roman Empire will adopt for its official state religion, Judaeo-Christianity, the religion of the oppressed, of women and slaves.

That imperial mantle, with the removal from Rome to

Constantinople of the Emperor, of a religion of shepherds and

fishermen, women and slaves, next fell upon the Bishop of

Rome, Peter's successor, who adopted the pagan priestly title

of Pontifex, 'Bridgebuilder', and who also, though few today

recognise this, adopted the stance and even the garb of Aaron the High Priest in the

Temple. The Lateran Basilica was consciously redesigned to be

as Rome's Jerusalem Temple, and Helena

and Constantine gave to it the supreme treasure of the Temple,

the Ark, to be housed in its Holy of Holies. That Holy of

Holies was only to be entered once a year by the Pope whose

triple tiara even, though no longer worn by Popes, was that of

Aaron. There is much wisdom in the Vatican's decision to lay

aside the papal triple tiara. Perhaps ecumenically Quakerism,

Anglicanism, Catholicism, Judaism and Islam can come to

acknowledge the 'royal priesthood' of every individual in the

image and likeness of the Creator. Pope John Paul II, writing

the apostolic letter, 'Mulieris Dignitatem', of 1988, noted

that Christ is 'the supreme and only priest of the New and

Eternal Covenant', yet that 1 Peter 2.9's 'royal priesthood'

is the treasure which 'he has given to every individual'. The

Kingdom of God within us and among us here on earth is a

priestly kingdom, a royal priesthood, of all believers, knit

together with simple sacraments, with water, bread and,

(except for Islam) wine, and, potentially, the peaceable,

saving and healing olive.

Bibliography

The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Trans.

Betty Radice. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

Adai and Mari. The Liturgies

of the Holy Apostles Adai and Mari together with the

Liturgies of Mar Theodorus and Mar Nestorius and the Order

of Baptism. Ed. Mar Thoma Darmo Metropolitan. Trichur,

South India: Mar Nasai Press, 1967.

Alter, Robert and Frank Kermode,

editors. The Literary Guide to the Bible. London:

Fontana, 1987.

The Liturgical Portions of

the Apostolic Constitutions: A Text for Students.

Trans., ed., annotated and introduced, W. Jardine Grisbrooke.

Bramcote: Grove Press, 1990. Alcuin/GROW Liturgical

Study 13-14.

Aprem, Mar. ‘The Chaldean Syrian