JULIAN'S SHOWING OF LOVE IN A NUTSHELL:

HER MANUSCRIPTS AND THEIR

CONTEXTS

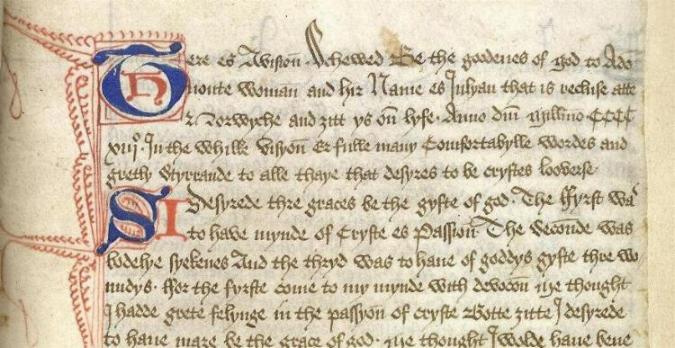

I. The Amherst Manuscript

The oldest manuscript we have is possibly the last version of Julian's text of her Showing. It is the Short Text in the British Library, in the Amherst Manuscript , written about 1413 to about 1435, by a scribe, possibly the Carmelite Richard Misyn himself, from Lincolnshire, of texts assembled finally for an anchoress, Margaret Heslyngton. The version of Julian'sShowing of Love this manuscript includes clearly states that it was written out in 1413 [.Anno domini millesimo CCCC/ xiij.], when Julian was still alive, 'and 3itt. ys oun lyfe'. In the years from 1408-1413 Chancellor Archbishop Arundel was vigorously suppressing Lollardy and forbidding the Bible in English. This version of Julian's Showing cuts out the scriptural translations the other versions included, speaks often of the need to comply with Holy Church's regulations, yet equally often speaks of the need for charity for one's 'even Christian', a concept that is both from the Gospels and Lollard teaching. The manuscript excludes Julian's earlier discussion of Jesus as our Mother as perhaps too dangerous, but has a drawing at its conclusion of a cross-nimbed Mother, the cross being formed by the three nails of the Crucifixion, while the Child has no halo at all, which may indicate that the Mother is intended as Jesus, the Child as ourselves. This 1413/perhaps circa 1435 manuscript was re-discovered in 1911.

![]()

ere es Avisioun. Shewed

Be the goodenes of god to Ade/uoute Woman and hir Name es

Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt ys oun

lyfe. Anno domini millesimo CCCC/xiij. In the whilke visioun

er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to

alle thaye that desyres to be crystes looverse/

ere es Avisioun. Shewed

Be the goodenes of god to Ade/uoute Woman and hir Name es

Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt ys oun

lyfe. Anno domini millesimo CCCC/xiij. In the whilke visioun

er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to

alle thaye that desyres to be crystes looverse/

By Permission of The British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97. Reproduction Prohibited.

It continues with:

Desyrede thre graces by the

gyfte of god. The ffyrst was to have mynde of Cryste es

Passiou n. The Secounde was/ bodelye syekenes

And the thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=undys.

ffor the fyrste come to my mynde with devocio un me

thought/ I hadde grete felynge in the passyoun of

cryste Botte 3itte I desyrede to haue mare be the grace of

god. me thought I wolde have bene ~

Desyrede thre graces by the

gyfte of god. The ffyrst was to have mynde of Cryste es

Passiou n. The Secounde was/ bodelye syekenes

And the thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=undys.

ffor the fyrste come to my mynde with devocio un me

thought/ I hadde grete felynge in the passyoun of

cryste Botte 3itte I desyrede to haue mare be the grace of

god. me thought I wolde have bene ~

Below is a diplomatic transcription of the Amherst Manuscript at folio 99, on the hazel nut.

The second oldest surviving manuscript is in the Westminster Manuscript , owned by Westminster Cathedral and now on loan to Westminster Abbey. The florilegium, or gathering of texts, including Psalm commentaries, parts of Hilton's Ladder of Perfection, and Julian's Showing of Love , was likely written out about 1500, but bears the date on the first page of '1368', which is repeated on the spine and on the end papers.

Westminster Cathedral Manuscript, '1368'

The section on the Showing of Love is quite different from the British Library's Short Text. It includes much of Julian's brilliant theology, of the entire cosmos as if it were but the size of a hazel nut in the palm of her hand, of God in a point, of Jesus as our Mother. It includes none of the death-bed vision that occurred in 1373 when Julian was thirty. It makes use of the Scriptures and where it uses the Hebrew Scriptures it does so with a knowledge of the original Hebrew texts, specifically two passages from Exodus, translating these into medieval English. This 1368?/1500 manuscript was discovered in 1955 but has been neglected by most Julian scholars.

Below are given folios 74-75 from the Westminster Manuscript, the original given within careful line and margin rules, presenting the discussion on the hazel nut:

Westminster Cathedral Manuscript

And

in

şis

he

shewed

me a lytil

thyng şe quantite of a hasyl

nott. lyeng in şe pawme of

my hand as it had semed. and

it was as rownde as eny

ball.

I loked şer upon wt şe eye

of

of my vnderstondyng. and I

şought what may şis be. and

it was answered generally

thus.

It is all şat is mad. I

merueled

howe it myght laste. for me

şought it myght soden

ly haue

fall to nought for

lytyllhed. &

I was answered in my vnder=

stondyng. It lastyth & euer shall

for god louyth it. and so

hath

all thyng his begynning

by

şe loue of god. In this

lytyll

thyng I sawe thre

propertees.

The fyrst is. şt god made

it. şe

secunde is şet louyth

it. & şe şrid

is. şat god kepith it. But

what

is şis to me. sothly şe

maker.

şe keper & şe louer. for

tyll I am

substancially oned to hym. I

may neuer haue full

reste ne ve=

rey blysse. that is to sey,

şat I

be so fastened to hym şat

şer

be no thynge şt is made be

twene my god & me. This

litil

thynge şt is made. me

thought

it myght haue fall to nought.

for lytillness. Of this

nedith vs

to haue knowynge şat it is

lyke

to nought all şyng şt is

made.

for to loue & haue god

şat is vn=

made. ffor şis is şe cause

why

şt we be not all in ese of

harte

& soule. for we seke

here reste.

In this thyng şt is so

lytyll where

no reste is in. and know not

our

god şat is allmyghty. all

wise

& all good. for he is

verey reste.

God wyll be knowen. & it

likith

hym şt we reste vs in hym.

for all

şat is beneth hym sufficith

not

to vs. And şis is şe cause

why

şat no soule is rested. tyll

it be

noughted of all şat is made.

and when he is wylfully nou=

ghted for loue. to haue hym

şt

is all. then is he able to

resceue

goostely reste.

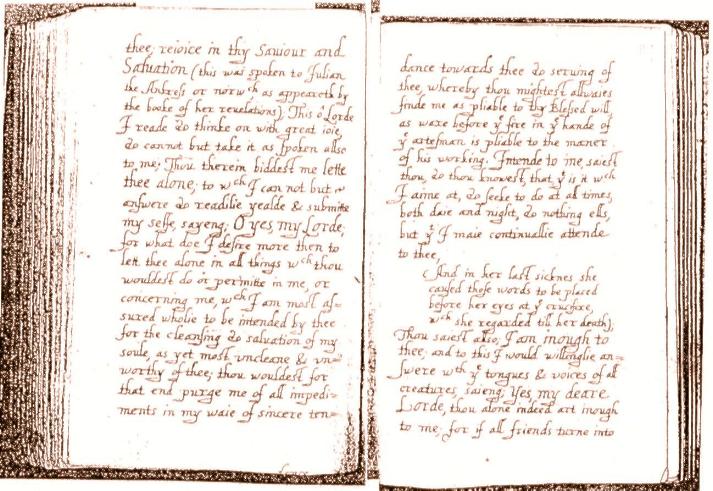

The third oldest surviving manuscript was written out about 1580 in the region near Antwerp, according to its watermarks, then was taken to Rouen and finally entered the Library of the King of France in 1706. It is now Bibliothèque Nationale, Anglais 40, and is called the Long Text. It likely copies out a Tudor 'fair copy' of Julian's text being readied for printing, then blocked by the Reformation. It includes all the material that is in the Westminster Manuscript, plus a frame of XV Showing, like the Brigittine XV Os , in which Julian in 1373, at the point of death, sees the Crucifix brought to her for the Last Rites where Christ's head bleeds, followed by a XVIth Showing that comes to her later and over which she ponders. This may be the Showing of the Parable of the Lord and the Servant, in which the Servant, who is both Adam and Christ, runs forth from the Lord, who is God and who sits in a blue robe in the wilderness. But the Servant is merely dressed in a dirty white shirt, which is our humanity, and next falls into a deep ditch as fallen Adam. He then is able to return to his beloved Lord and to sit at his right hand, garbed in rainbow colours, as Christ. It also includes the famous passage, 'All shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well'. Again Julian is translating from the Hebrew into English, rather than from Jerome's Latin. For 2 Kings 4 in the King James, which is translated from Hebrew, so translates 'shalom', which has the meaning of 'all', 'wholeness', 'all being well', where Jerome and Wyclif merely had it be 'Recte' and 'right'. She is also using a Hebrew reading where she describes herself as like Jonah reciting Psalm 139.9 (Jonah 2.3-6), on the deep sea bed amidst seaweed.

Here is given folios 8 verso and 9 recto of the Paris Manuscript of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love , in which we are looking at an Elizabethan manuscript copy by a nun of a Tudor 'fair copy' Syon manuscript readied for printing, that was blocked by Henry VIII's Reformation:

Below are given transcriptions of these folios 9-10v in the Paris Manuscript, in the original presented with careful line and margin rules, on the hazel nut:

The first reuelation - //-

||P It

is all that is made. I marvayled

how it might laste, for me

thought it might

have fallen sodenly to nawght for

littlenes ||P And

I was answered in my

vnderstanding.

it lasteth and ever shall.

for god loueth

it. and so hath all thing

being by the

loue of god, ||P In

this little thing

I saw .iij. proprties, ||P the

first is şt

god made it, ||P the

secund that God

loueth it, ||P the

thirde that god kepyth

it, ||P But what behyld I verely the ma=

ker. the keper. the louer.

for till I am

substantially vnyted to him

I may ne=

ver haue full reste. ne

verie blisse. şt

is to say. that I be so

fastned to him

that ther be right nought

that is made

betweene my god and me, ||P

This

little thing that is made me

thought

it might haue fallen to

nought for

littlenes, ||P

Of this nedeth vs to

haue knowledge. that vs

lyketh nought

all thing that is made. for

to loue god

The fyft Chapter

and haue god that isvnmade, ||P

ffor this

is the cause why we be not

all in ease of

hart and of sowle; for we

seeke heer rest

in this thing that is so

little wher no

reste is in, and we know not

our god

that is almightie all wise

and all good

for he is verie reste; ||P God

will be

knowen and him lyketh that

we rest

vs in him,

||P ffor all that is

beneth

him suffyseth not to vs, ||PAnd

this

is the cause why that no

sowle is in

reste till it is noughted of

all thinges

that is made: when she is

wilfully nough=

ted for loue, to haue him

that is all,

then is she able to receive

ghostly reste,

||P And

also our good lord shewed şt

it is full great plesaunce

to him that a

sely sowle come to him naked

pleaynly

and homely, ffor this is the

kynde

dwellynge of the sowle by

the touchyng

of the holie ghost, as by

the vnderstan=

dyng that I haue in this

schewying,

The first reuelation

God of thy goodnes geue me

thy selfe for thou

art Inough to me. and I maie

aske nothing

that is lesse that maie be

full worshippe to

thee, and if I aske anie

thing that is lesse

ever me wanteth, but only in

thee I haue

all. ||P And these wordes god of the good=

of godnes thei be full

louesum to the sowle

and full neer touching the

will of our

lord for his goodnes

fulfillith all

his creaturs and all his

blessed workes

ouer passeth wtout end, ||P

ffor he is

the endlesshead and he made

vs only to him

selfeù and restored vs by

his precious passion.

and ever kepeth vs in his

blessed loue and

all this is of his goodnes

//- //- //

The vith Chappter //- //-

//-

{ This shewing was geuen to

my vn=

derstanding to lerne our

soule wi=

sely to cleue to the goodnes

of god. and

in that same tyme the

custome of our

praier was brought to my

mind. how

If we study the

dates that actually appear in the three manuscript versions of

Julian's Showing a most interesting pattern emerges.

The Westminster Manuscript, which has nothing of the death-bed

vision and which has the date '1368', could represent a first

version written out when Julian was twenty-five. The Paris

Manuscript Long Text tells us that its original version was

being conceptualised and written fifteen and twenty years

after the 1373 vision, that is, when Julian was between

forty-five and fifty years of age. The Amherst Manuscript

Short Text clearly tells us it was written out in 1413, when

Julian was seventy. These manuscript versions could thus

represent a lifetime of a woman's theological writings. But

the manuscripts tell a story of an even greater span of time,

a story which encompasses great troubles and tempests in the

history of the Church in England.

IV. Norwich Castle and Lambeth Palace Manuscripts

Two manuscripts

contemporary with the end of Julian's life and with the

Amherst Mansucript and somewhat later are to be found at

Norwich Castle and at Lambeth Palace. The hands of their

scribes are squarish, with a particular ampersand, and the

second typically dots ys as well as is to

distinguish them from the thorns. The Norwich

Castle Manuscript transcribes 'Epistle sent Jerom

[actually Pelagius] sent to amayd Demetriade that had vowed

chastite to ihsu criste', a Treatise on the Lord's Prayer , the Carmelite Richard

Lavenham's Treatise on the Seven Sins, and Pore Caitif. The Lambeth Palace Manuscript contains

contemplative prayers in Latin and English. Many phrases

within these texts echo Julian's theology, yet neither contain

Julian's Showing of Love. The hand of the Norwich

Castle Manuscript is similar to that of the corrector of the Amherst Manuscript adding missing and

important lines to the text of the Showing of Love.

V. The Syon Manuscripts' History

The three earliest Showing manuscripts, Amherst, Westminster and Paris, were each associated with Syon Abbey, the Brigittine monastery founded in England by King Henry V to expiate his father's murders of Richard II and Archbishop Richard le Scrope of York. Richard Misyn of Lincoln, the Carmelite translator of Richard Rolle's texts, came to be closely associated with Archbishop Richard le Scrope of York.

The Short Text Amherst Manuscript was written out for contemplative women and also includes Margaret Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls , Jan van Ruysbroeck's Sparkling Stone , an extract from Henry Suso's Horologium Sapientiae , and works by Richard Rolle, translated by Richard Misyn, for women recluses, as well as Julian's Showing of Love. The scribe's dialect is identified as from Grantham, Yorkshire, the same scribe being responsible for other major manuscripts, including Mechtild of Hackeborn's Book of Ghostly Grace . The Amherst Manuscript constantly uses the monogram 'SI'. The drawing at its conclusion, where Jesus is as Mother, is shown with a cross-nimbed halo made of three nails, appears to reflect the Brigittine headdress of the five wounds made by three nails and spear in Christ's body. The manuscript is then heavily annotated by James Greenhalgh, a monk of Syon Abbey's twin foundation, Carthusian Sheen.

The Westminster Manuscript came to be owned by the Lowe family, Christopher de Hamel noting that that family also, at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, owned a Syon Psalter, now in Edinburgh. Philip Lowe and his wife and John Lowe, a priest, were arrested and imprisoned and John Lowe was drawn hung and quartered for their Catholicism and their association with Syon Abbey's young nuns returned in disguise, under Elizabeth I. Rose Lowe became a Brigittine nun at Syon in exile in Lisbon in the early nineteenth century and saved Syon from extinction. John Bramston was the last Brigittine monk buried at Syon Abbey before the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Bramstons were reported by a Portuguese spy as being secretly Catholic. Bishop James Yorke Bramston, who did his theological training at the English College, Lisbon, came to own this manuscript, calculating on its end paper in 1821, by subtracting 1368 from it, that it was 453 years old. Both families involved with the ownership of this manuscript have demonstrable Syon Abbey connections. Moreover the hand of the manuscript is most closely identified by Jean Preston with one in another manuscript owned by a Brigittine nun at Syon. It is likely written out by a Brigittine nun.

The Paris Long Text Manuscript

clearly has Antwerp watermarks of about 1580, which is the

date at which exiled Syon was in Antwerp. The manuscript then

came to Rouen, which is where Syon Abbey next journeyed, then

was sold off when Brigittine Syon's nuns sailed away to Lisbon

in 1594, coming into the hands of the Bigot family of book

collectors in Rouen, before it was auctioned off to the King

of France's Library in 1706. It, too, is likely written out by

a Brigittine nun.

VI. The Benedictine Manuscripts: Gascoigne, Upholland, Sloane, Stowe

The Long Text exists in three further versions, made together in the seventeenth century, Sloane 2499 and 3705, which are almost complete, and Stowe 42, which is complete apart from eyeskips. There are as well two seventeenth-century fragments copied from these Long Text versions, one at at St Mary's Abbey, Colwich, and written out byDame Bridget More , the great great great great granddaughter of Thomas More, from a text originally copied by Dame Margaret Gascoigne,

the other formerly at Upholland, written out by Dame Barbara Constable ,

the above portraits of both these scribes also surviving.

These five manuscripts were all transcribed by

English Benedictine nuns in exile at Cambrai and Paris (now

Stanbrook Abbey and St Mary's Abbey, Colwich). They were

observing the precepts of Fathers Augustine Baker and Serenus

Cressy, O.S.B., who had encouraged the nuns to read

fourteenth- century contemplative writings and to transcribe

them for their own devotional use. Father Serenus Cressy was

to publish the first printed edition of Julian of Norwich's Showing

of Love in 1670.

You can even visit virtually the Colwich Abbey Benedictines in England who, in exile, had so carefully preserved Julian's Showing~

Thus we

owe the preservation of Julian's magnificent Showing

first to Brigittine, then to Benedictine contemplative

nuns.

I

studied the two Sloane Manuscripts, 2499 and 3705, of

Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love

(sigla: S1; S2) in the British Library, admiring their

marginal notations - in the same lovely hand and whose

Nota Bene is made with the first stroke of the B being the

last stroke of the N, that B having the long ascender

curve over upon itself. Stowe 42 has been thought to be a

painstaking imitation by a reader of Serenus Cressy's 1670

first edition of The Revelations of Divine Love. I

asked the Librarian if I could examine all four texts at

the same time, Sloane 2499 and Sloane 3705 with Stowe 42

and the Serenus Cressy 1670 printed edition. Several

things became clear. Stowe 42 is almost exactly the same

as the printed edition, except that the name of the editor

in Stowe 42 is signed in an elaborate cursive hand, 'H.

Cressy' (Hugh Paulinus having been his baptismal names),

rather than as in the capital letters of the printed

edition, nor does Stowe 42 give the 1670 edition's

publishing information. Moreover in both Stowe 42 and in

the Serenus Cressy 1670 edition shoulder notes gloss the

obscure words in the text; some of these in Stowe are

lacking, not yet having been determined, but only

indicated by means of asterisks, daggers and so forth,

showing where they should be later supplied. These glosses

are then arrived at through the consultation of the two

Sloane manuscripts, and coincide as a rule with their

marginal comments, such as NB, and with the related word

written in those two texts. Chapter Three in Stowe 42 has

a significant eye-skip, it omits 'oftentimes to have

passed, and so weened', which is present in the Cressy

printed edition (siglum C2). There are also others. These

could indicate that Stowe is a copy of Cressy. However,

the correction of the eye-skips can be explained by the

careful checking that was clearly done, likely at page

proof stage, and most likely by Serenus Cressy, of his

prototype against S1 and S2, where the eye-skipped

sections are present and thus supply the lacunae. At first

I believed with these findings that Stowe 42 was likewise

a product of the English Benedictines, more likely this

time in Paris than Cambrai, and just prior to the 1670

printing of C2, but W.H. Kelliher of the British Library

checked the watermarks to find it to be clearly English

and Georgian. It is just possible that Stowe 42 copies the

likely Tudor exemplar manuscript to Cressy's edition of

1670, and that it was copied out on the Benedictine nuns'

return to England following the French Revolution.

The Sloane Manuscripts (sigla SS) copy out a different and now-lost medieval exemplar of Julian's Showing of Love, owned by the Benedictine nuns at Cambrai and perhaps taken by them to Paris. The exemplar to the Sloane Manuscripts, however, is not the same as the now-lost Tudor exemplar to be copied out in Stowe 42 and in the Serenus Cressy 1670 edition, which was also owned by the English Benedictine nuns in exile and which was first quoted from by Dame Margaret Gascoigne, O.S.B., before her death in 1637. The latter two texts, Stowe and Cressy (sigla CC), give the second most complete version of Julian's Showing of Love in the Long Text that have come down to us, corresponding almost exactly with the Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Anglais 40 (siglum P), Manuscript, which was initially written out by an exiled Brigittine nun in Antwerp circa 1580, and which then came to Rouen, where it entered the Library of the Bigot family, in turn being sold to the King of France's Royal Library in 1706 (which become the Bibliothèque Nationale at the French Revolution). The Paris Manuscript was thus neither available to the Benedictine English nuns nor to their 1651-1653 spiritual director, Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., the manuscript not having yet reached Paris from Rouen by these dates. One of the manuscripts the English Benedictines used must thus have been the Tudor exemplar of the Paris Manuscript. It is therefore important to heed the readings of Stowe 42 (siglum C1) and Cressy 1670 (siglum C2). However, the dialect of the Tudor exemplar to Paris and Stowe was likely already flattened by the Syon Abbey Brigittines. But the medieval exemplar to the Sloane Manuscripts (SS), though it presents a shorter version of the Long Text, was close to Julian's own Norwich dialect and corresponds with the Norwich Castle Manuscript written for or by an anchoress in that region. It is a blessing that Dame Clementia Cary, O.S.B., took such care to preserve its original spelling in S1. Thus all these seventeenth- and eighteenth-century readings of a fourteenth-century text need to be heeded.

Sloane 2499 (siglum S1), appears to be copied out rapidly by Dame Clementia Cary, O.S.B. , about 1650, while taking great pains to be faithful to the archaic dialect of the exemplar. Dame Clementia Cary, O.S.B., became the Mother Foundress, with Dame Bridget More, the first Prioress, of the Paris Our Lady of Good Hope English Benedictine house (today, Colwich Abbey in England, founded in 1651 from Cambrai's Our Lady of Comfort English Benedictine mother house, founded in 1620. We do not know who inscribed the second Sloane manuscript. Sloane 3705 (siglum S2). It has been tended to be thought late, perhaps eighteenth-century. Its spelling is modernised. But it takes great pains with italicizing and engrossing to reproduce the layout of its medieval exemplar. That its annotations and layout came to be used in Stowe 42 and in Serenus Cressy's 1670 editio princeps indicates that it is closely contemporary with Sloane 2499 (siglum S1). Moreover some of its annotations are in Dame Clementia Cary's hand and appear to be her response to her initial reading of Julian's Showing . Thus Sloane 3705, S2, may precede Sloane 2499, S1, in the manuscripts' chronology. A check of its watermarks by W.H. Kelliher of the British Library also reveal that it actually precedes S1 in time. A fragment of the Showing, copied out by Dame Barbara Constable, O.S.B., now in the Upholland Northern Institute (siglum U) collection, recreates the same engrossing as do Sloane 3705 and Stowe 42, engrossing also seen in one instance in the Westminster Manuscript. Dame Bridget More, O.S.B. , in turn also copied out a fragment of a Julian manuscript, her copy to be found in that house, now St Mary's Abbey, Colwich, which returned to England following the French Revolution (siglum G). This text likewise makes careful use of engrossing in the text. That the second Sloane manuscript, like Dame Barbara Constable and Dame Bridget More's two fragments from Julian's Showing, is most careful to place Christ's words to Julian in larger letters or with underlining, to differentiate these from the rest of their text, may be evidence, where three scribal witnesses concur, of Julian's own scribal practices.

The fact that the second Sloane manuscript, like the first Sloane manuscript, has marginal notations which become the shoulder glosses in Stowe 42 (C1), and which are printed in 1670 (C2), leads us to several conclusions. It is significant that all three manuscripts were in England before the return of the exiled English Benedictine nuns. The other fragmentary copies from medieval manuscripts remained with them in Paris, not returning to England until the nineteenth century. Who could have brought the Sloane Manuscripts to England? The logical answer is that these manuscripts were gathered together and carefully compared and prepared by Dame Clementia Cary, O.S.B, and her fellow Benedictine nuns for the 1670 first edition by Serenus Cressy, O.S.B. The different hands of many of the learned annotations and most careful editorial comments are still to be identified. What is clear is that a team of Benedictine editors further compared the text prepared for publication of a now lost medieval exemplar text with two slightly different texts from a related manuscript family, similarly prepared by them for such a purpose. Thus all their dates must precede that of 1670. Sloane 3705 is therefore coeval with Sloane 2499, likely circa 1650. The Sloane Manuscripts are written out in France, then brought home to Julian's England by the exiled English Benedictines' chaplain, Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., for the flower ornaments to the editio princeps made from these manuscripts are English rather than French. Following that there is a significant gap in these manuscripts' history.

Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), whose collection of manuscripts became the nucleus of the British Library, died prior to the French Revolution. His collection exemplifies his great interest in medicine and related subjects such as alchemy. It appears that Sir Hans Sloane acquired his two manuscripts, Sloane 2499 and Sloane 3705, quite early, perhaps out of medical interest in Julian's description of her near-dying. But what of Stowe 42? The Stowe Manuscripts were lodged for a while at Ashburnham Place in Sussex, following the Duke of Buckingham's bankruptcy in the nineteenth century, before coming to the British Library. Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., had died and was buried near Ashburnham in Sussex, 1674. Perhaps Stowe 42 made its way into the Ashburnham Place collection, rather than into that initially at Stowe, and then into the British Library? However, its watermarks indicate that it was copied out at the end of the eighteenth century and in England, and could have been a gift from the English Benedictine nuns to thank their benefactress and patroness, the Marchioness of Buckingham.

Let us

now look more closely at this second generation of

Julian's Showing of Love Manuscripts,

generated in a Benedictine context, rather than a

Brigittine one:

We can compare this text with the two Sloane Manuscripts' readings of the same passage, as did Serenus Cressy when preparing his edition. Sloane 2499 is written hastily by Dame Clementia Cary, O.S.B., but which carefully replicates its Middle English spelling, likely from a desire for its preservation, while glossing the more modern form in its margin, of 'lesten', as 'last', but it does not follow the exemplar manuscript's layout. This is from Sloane 2499, fol. 4.

suddenly

have fallen to nought for little,

And I was answered

in my understanding;

it lasteth and

ever shalle, for God loveth it.

And so alle things

have a being by the loue

of God.

VIII. The 1670 Serenus Cressy First Edition

This is the same section on the hazel nut as it appears in Serenus Cressy's 1670 printed edition, pages 11-12:

____________________________________

12 The

First Revelation . Chap. 5

____________________________________

round as a Ball. I

looked theron with the

eie of my

understanding, and thought, What

may this be ?

and it was answered generally thus.

It is all that

is made . I marvelled how it

might last: For me

thought it might sodenlie

have fallen to

naught for litlenes.

And I was answered

in my Understanding,

It lasteth,

and ever shall: For God loveth it.

And so hath

all thing being by the Love of

God.

In this litle thing

I sawe threePrope-

ties.

The Stowe Manuscript is carefully written out in an italic hand, with its running headers, demonstrating how its pages are to be or were typeset by a printer. The scribe used a distinctive d whose ascender curls back over on itself. Initially my hypothesis was that this was the fair copy for Serenus Cressy's edition, but an examination of the watermarks shows that it was likely produced by the English Benedictines following the French Revolution, for the first time Julian being written out on English water-marked paper, at the end of the eighteenth century.

Us,

and all becloseth us, hangeth about us for tender

Love, that he-

maie never Leave

us. And so in this sight I saw that he is all thing

that

is good, as to my

understanding.

And in this he shewed

a Litle thing, the quantitie of a Hasel-Nut , Ly=

in the Palme of

my hand, as me seemed, and it was as round as a

Ball. I looked

thereon with the eie of my understanding, and

thought,

What may this be?

and it was answered generally thus,

It is all that is

made. I marvelled how it might Last. For me thought

it might sodenlie

have fallen to naught for Litleness.

And I was

answered in my understanding, It Lasteth, and ever

shall;

For God loveth

it. And so hath all thing being by the Love of God.

In this Litle

thing I saw three Properties.

But what beheld I

therein? Verilie the Maker, the Keeper, the

Lover: For till I

am substancially united to him, I maie never have

full rest, ne

verie bliss; that is to saie, that I be so fastened

to him,

that there be

right nought that is made between my God and mee.

And now

we must go backwards through time, exploring the

archeology of Julian's Showing, understanding how

it came to be preserved, even where it had to be hidden

and hoarded, rather than revealed and shown, perhaps,

because, like her own image of a homely hazel nut, it was

beloved, despite persecution both from without and from

within, within Julian's context of enclosed monasticism.

X. Their Benedictine Context

The story of these manuscripts is a deeply moving one. It tells us of scholarly men, in their direction of the lives of religious women, encouraging the use of earlier mystical and theological texts written by men and by women. There were two such directors for the English Benedictine nuns in exile. The first was Father Augustine Baker, O.S.B., who had worked for Sir Robert Cotton and knew his superb collection of medieval manuscripts, which later entered the British Library. Father Augustine Baker, O.S.B., encouraged the nuns at Cambrai to read, copy and use the medieval mystics in their own contemplative lives. Other, and male, Benedictines balked at this practice. The nuns were asked to surrender their books. A burst of copying ensued, Dame Barbara Constable, O.S.B ., providing the greatest amount of copied texts, among them the Upholland fragment of Julian's Showing, and likely also Dame Clementia Cary's hastily written complete version in Sloane 1 , following upon the ecstatic comments to the margins of Sloane 2 , and a small group of nuns went to Paris with the resulting duplicated collection of texts as insurance against their loss. Their director in Paris was Father Serenus Cressy, O.S.B. Likewise the Paris Constitution, in French, written out in Dame Bridget More's exquisite hand, in English, in Dame Clementia Cary's, included the information that the English Benedictine nuns' spiritual lives were to be based, as Father Augustine Baker, O.S.B., had carefully taught them, upon these practices.

In these

Julian of Norwich Showing manuscripts and their

1670 first edition we witness a kind of Earlier English

Text Society, a careful editing of texts using scholarly

methods and indeed being more accurate in replicating

their manuscript versions than are modern editors such as

Edmund Colledge and James Walsh, while at the same time

doing so for their own and others' spiritual sustenance

and growth. It is all the more poignant that this crucial

work of the preservation of an English medieval text

written by a woman was being carried out by

seventeenth-century women and men in exile from England,

and that this band included four direct descendants of St

Thomas More, as well as several relatives of Sir Thomas

Gascoigne, Chancellor of Oxford University and benefactor

of Syon Abbey. I tried to discover why these families no

longer sent their daughters to Syon Abbey, then in exile

in Lisbon, and found in the bowels of Exeter University

Library notebooks giving information concerning a libelous

book printed against Syon by a licensed pirate who entered

the Abbey, pretending to be Catholic, becoming ordained a

priest monk, then fleeing in the night with treasure and

manuscripts. The year following that publication the

English recusants founded Benedictine Cambrai. It is clear

that these young women continued to treasure Julian's

text, whether in Brigittine or in Benedictine houses in

England and in exile. One sees in these manuscripts and

their first edition a most courageous collaboration on the

part of Benedictine monks and nuns in exile. We are

greatly in their debt. Serenus Cressy. O.S.B., also edited

Augustine Baker, O.S.B.'s papers, compiling from them Holy

Wisdom (Sancta Sophia, Douay, 1657), a work

which has remained the handbook for the spiritual

direction of both Catholic and Anglican, men and women,

religious in exile and in England, since its publication.

XI. Their Brigittine Context

The

three earliest manuscript versions of Julian's Showing

are the Westminster Cathedral

Manuscript , now on loan to Westminster Abbey

(siglum W), which gives the date '1368' on its first folio

but which is written out, most likely in a Brigittine

context, around 1500, from another written out around

1450, the Amherst Manuscript ,

British Library, Additional 37,790 (siglum A), which gives

the Short Text of Julian's Showing, dated

internally 1413, when, as it states, Julian is still

alive, and which was copied out by a Grantham,

Lincolnshire, scribe, the manuscript coming into the

context of Carthusian Sheen and Brigittine Syon, and the Paris Manuscript copied out by

Brigittine in exile from the Dissolution of the

Monasteries in the Antwerp region circa 1580.

Neither the Westminster nor the

Amherst texts are as complete as

are the Paris and Stowe , or even Sloane , versions. But they are the

earliest we have. They are also very different from each

other. Westminster Cathedral has no reference to the 1373

death-bed vision, making one take its '1368' date

seriously. Amherst betrays all the fear one would expect

following Arundel's Constitutions aimed against the

Lollards and any use of the Scriptures in English

translation, especially by women, a terror that had

crescendoed by 1413, the date of Sir John Oldcastle's

Lollard Revolt. Each shares their material with the two

manuscript families of the Paris/Stowe/Cressy and Sloane

textual versions; with the exception of Amherst's

interpolations stressing Julian's inadequacy as a woman to

teach theology, and a concurrent stress upon minute

details of the near-death visionary experiences, as if

seeking authorization. These two manuscript versions share

no material with each other that is not found in the

Paris/Cressy versions. Benedictine Serenus Cressy did not

have access to the Brigittine Westminster, Amherst or

Paris Manuscripts. Thus we need to understand why the

manuscript families of Julian's Showing appear in

both Benedictine and in Brigittine contexts.

XII. Anchoress and Cardinal

I found a link when struggling to answer the following question: How could a woman of only twenty five years of age in medieval Norwich have been able to write such brilliant theology as is expressed in the Westminster Manuscript if it were to have originally been written in '1368', the date given in that manuscript? We now have a young Carmelite from Normandy, St Therese of Lisieux, who died at that age, proclaimed a 'Doctor of the Church'. Women under contemplative, cloistered monasticism, such as with the Carmel, in Benedictinism, in Brigittinism, or in an anchorhold, share with Augustine's Confessions, a continuous conversation of prayer with God. The answer may lie in Julian's possible Benedictinism. She came to be an anchoress at St Julian's Church by 1393/94. That church was given to the Benedictine nuns of Carrow Priory at its foundation by King Stephen in 1146. Carrow Priory in turn was under the Benedictine Norwich Cathedral Priory. Contemporary with Julian in Norwich was an equally brilliant Benedictine, Adam Easton . He was sent by the monks in 1350 to study and eventually to teach theology at Oxford, where he specialized in Hebrew and came to translate the whole of the Hebrew Scriptures into Latin. He and Thomas Brinton, who was later to become Bishop of Rochester (and whose sermons, which influenced Piers Plowman, survive, edited by Sister Mary Aquinas Devlin, O.P.), were both summoned in 1352 to Norwich to preach to the laity, and finally did so return in 1356-1367. Next both Thomas Brinton and Adam Easton worked at the Papal Curia, first in Avignon, then Italy, where they knew Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena , who were women writers of visionary books.

Adam Easton became Cardinal of England in 1381, his titular church being St Cecilia in Trastevere (mentioned by Julian in the Amherst Manuscript in engrossed letters and likewise mentioned in a manuscript in Norwich Castle written for and possibly by a Norwich anchoress), but he was imprisoned in a dungeon by Pope Urban VI, 1385-1389, and almost executed, five other Cardinals so dying. Richard II and the President of the Chapter-General of the Benedictine Order in England pleaded for Adam's life in eloquent letters, citing the Good Samaritan Parable. Because Adam had prayed to Birgitta that if his life were saved he would work for her canonisation he now did so, reading all the canonisation documents and her Revelationes and writing a treatise, the Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae, which he presented to Pope Boniface IX in 1391. He especially included in it material supportive of women's visionary writings. In it he specifically answers a charge made by a Perugian that women cannot hear or see visions of God, by observing that the Resurrection was announced to the Apostles by women, especially by Mary Magdalene, the first to see and hear the Risen Christ, that women were present at the Pentecost, and that in Acts 21 Philip's four virgin daughters were prophetesses. He goes on to speak of the Virgin Saints, Agnes (to whom Peter appeared in a vision), Agatha and Cecilia, and then discusses Peter's 'Quo Vadis' vision of Christ at Rome and St Thomas' vision of Christ at Jerusalem. Peter and Thomas denied and doubted Christ; these many women exemplify the deepest faith.

There are records of large payments for the shipments of, first Master, then Cardinal, Adam Easton's books between Oxford and Norwich and the Continent and Norwich, first in 1363-1368 from Oxford, when Julian may have been writing the Westminster version of the Showing, and then in 1389-1390, by way of the Low Countries, when Julian was writing the Long Text version of the Showing. There were over 228 of these books at his death, shipped back from Rome finally in 1407 in six barrels, to be returned to Norwich Cathedral Priory's Library. Ten of these fine manuscripts still survive, scattered between Oxford, Cambridge and Avignon. Balliol has Adam Easton's copy of John of Salisbury's Policraticus , Cambridge has his Origen on Leviticus, his complete works of Pseudo-Dionysius, which includes Greek with its Latin, his astronomical writings, which give the years in arabic numbers, such as '1368' and which go so far as the years 2000, 80000 and 1000000, and which also include careful drawings on how to calculate the heights of Norwich Cathedral and Norwich Castle, and his copy of Rabbi David Kimhi, Miklol (Perfection), Sepher Ha-Shorashim (Book of Roots), whose philological theology stresses God as Mother, God as begetting us. The chapter headings given in the Sloane Manuscripts appear to be written by a contemporary to Julian of Norwich, they are in the Norwich dialect, and they sound much like the comments made by Birgitta of Sweden's editors to her Revelationes, by Magister Mathias in Sweden, and by Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jaen in Italy. (Interestingly, Alfonso of Jaen's similar text, supporting Birgitta, companion to that written by Cardinal Adam Easton supporting her, occurs in a Middle English Norfolk manuscript, and is echoed in the conclusion to Julian's Amherst Showing.) The chapter headings to the Sloane Manuscripts may be the work of Cardinal Adam Easton who is known to have written lost works on the spiritual life of perfection and treatises in the vernacular. While Julian herself returns again and again in all her texts to phrases given in Gregory's Dialogues II concerning Benedict, that follow immediately upon the story of Benedict's visit to his sister Scholastica .

Cardinal Adam Easton, O.S.B., died, 15 September 1397, or, according to his monument, 15 August 1398, and was buried in the church of St Cecilia in Trastevere in a fine marble tomb, with the arms of England and his cardinal's hat sculpted upon it; later his body, like that of St Cecilia's, was found incorrupt. Adam Easton laid the groundwork for England's 1415 foundation of Syon Abbey. Benedictine Adam Easton, a major supporter of Birgitta of Sweden, had been in Norwich at each of the periods when Julian would have been working on the three versions of the Showing , except the last, when he was dead and she was threatened by Archbishop Arundel's persecution of lay theologians, especially women, speaking and writing about the Scriptures in the English language. Moreover, Adam Easton's Basilica of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere in Rome, housed both Benedictine nuns and Brigittine monks through time.

The

keeping, the reading and and the copying of the Julian

Manuscripts clearly took place under Benedictine and

Brigittine auspices. The 1413/1450 Showing version

in the Amherst Manuscript stresses St Cecilia by writing

that saint's name in enlarged emboldened letters and notes

that St Cecilia had preached in Rome, though mortally

wounded by a sword in her neck three times. Could there

not be a connection between these two Norwich persons, the

one a monk, the other an anchoress, both of Benedictine

establishments, both with strong Brigittine links?

Indices to Umiltà Website's Essays on

Julian:

Preface

Influences

on Julian

Her Self

Her

Contemporaries

Her Manuscript

Texts ♫

with recorded readings of them

About Her

Manuscript Texts

After Julian,

Her Editors

Julian in our

Day

Publications related to Julian:

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

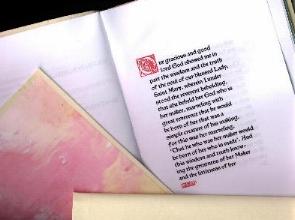

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

An

earlier version of this essay was published in The

Tablet, 11 May 1996, and is reproduced here by kind

permission of the Editor of The Tablet.

JULIAN

OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH

|| SHOWING OF LOVE || HER TEXTS || HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF

SWEDEN ||

BIBLE AND

WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S

IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS

|| BENEDICTINISM

|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST

MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS,

BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||