A CELL OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE: THE PILGRIMAGE WITHIN:

Catherine of Siena || Christina of Markyate || Angela of Foligno || Umiltą of Faenza || Margaret Kirkeby || Margaret Heslyngton || Emma Stapleton || Birgitta of Sweden || Chiara Gambacorta || Julian of Norwich || Francesca Romana || Elizabeth Barton

A Cell of Self-Knowledge: St Catherine of Siena

he young

Catherine of Siena immured herself in her room in prayer -

and later wrote or rather, dictated, of that time as her

'Cell of Self-Knowledge'. The Middle English Orcherd of

Syon translating her Revelation, her Dialogo,

states that such a soul

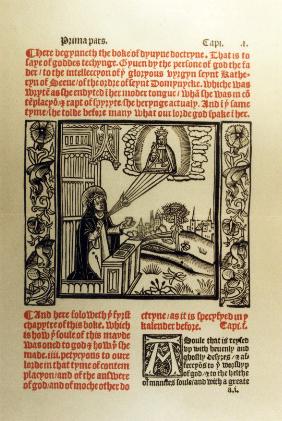

And here foloweth the fyrst/ chapytre of this boke. Which/ is how the soule of this mayde/ was oned to god & how then she/ made .iiii. petycyons to oure/ lorde in that tyme of contem/placyon and of the answere/ of god and of moche other do/ctryne: as it is specyfyed in the/ kalender before. Capt.1.

A soule that is reysed up/ with heuenly and/ ghostly desyers & af-/feccyo ns to the worshyp/ of god & to the helthe/ of mannes soules with a greate . . .

________

The Orcherd of Syon (Westminster: Wynken de Worde, 1519), Catherine of Siena's Dialogo in Middle English, its colophon: 'a ryghte worshypfull and deuoute gentylman mayster Rycharde Sutton esquyer stewarde of the holy monastery of Syon fyndynge this ghostely tresure these dyologes and reuelacions . . . of seynt Katheryne of Sene in a corner by itselfe wyllynge of his greate charyte it sholde come to lyghte that many relygyous and deuoute soules myght be releued and haue comforte therby he hathe caused at his greate coste this booke to be prynted'./

A manuscript now in the British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius E.1, its edges charred in the Cotton Library fire in 1731, tells us in Latin the story of a remarkable young woman of the twelfth century, Theodora, who came to be named Christina, Anchoress, then Prioress, of Markyate.

She tells Roger of her vision of Christ giving her his Cross to hold and Roger speaks amidst the Latin in Old English:

/Pp. 106-107/.

That decision is preceded by a vision, one that looks back to Gregory's Dialogues on Benedict and forward to Julian of Norwich and Catherine of Siena. In the Dialogue following that concerning Scholastica and Benedict in loving discourse upon heavenly matters all night, Benedict is seen one night in prayer, and at the same instant the whole world to shrink as into one beam of light. Here Christina sees the Queen of Heaven and all the angels.

/ Pp. 110-111/.

ngela of Foligno, a Franciscan tertiary, who

did not really choose to live in a physical cloister or a

physical cell, spoke of the fruits of contemplation as being

where one's soul becomes a room, a cell, in which one finds

the All Good, finds the entire Creation. This account, written

down at her dictation by Fra Arnaldo, her confessor and

spiritual director, often clandestinely, gives: ' anima mea est una camera . . . est ibi . . .

omne bonum'.

Et aliquando dum eram in praedictis dixit mihi Deus: Filia divinae sapientiae, templum Dilecti, delectum Dilecti. Et: Filia pacis, in te pausat tota Trinitas, tota veritas, ita quod tu tenes me et ego teneo te. Et una operationum animae est, quod intelligo cum magna capacitate et cum magno delectamento quomodo Deus venit in Sacramento altaris cum illa societate (IX: p. 215)/.

Et ego frater scriptor quaesivi ab ea si illa acies, postquam acies erat, si habebat aliquid mensurae in longitudine aliqua vel in latitudine aliquo modo. Et ipsa respondit quod non habebat aliquam mensuram in longitudine vel latitudine, sed erat ineffabiliter. (IX: p. 211)./

(Oportet quod homo cognoscat)

Iterum cum quaereretur ab ea quare oportet haberi paupertatem, dolorem et despectum, respondit: Oportet quod homo cognoscat Deum et seipsum.

Cognitio Dei praesupponit cognitionem sui hoc modo, ut videlicet homo consideret et videat quem offendit; postea consideret et videat quis est ipse qui offendit. Ex qua secunda consideratione et visione datur gratia super gratiam, visio super visionem, lumen super lumen.

Ex his incipit devenire ad cognitionem Dei. Et quanto amplius cognoscit, tanto amplius diligit; et quanto amplius diligit, tanto plus desiderat; et quanto plus desiderat, tanto fortius operatur. Et ista operatio est signum et mensura amoris; quia in hoc cognoscitur si amor est purus et verus et rectus, si homo diligit et operatur quod dilexit et operatus est ille quem diligit.

Sed Christus, quem diligit, habuit, dilexit et operatus est illa tria donec vixit; ergo qui eum diligit, debet eadam semper diligere, operari et habere sicut Christus ea habuit, ut habetur supra./

Perhaps Franciscan Angela of Foligno helped shaped Dominican Catherine of Siena's and Benedictine Julian of Norwich's concept of a 'Cell of Self-Knowledge'. Certainly the English Benedictine nuns in exile at Cambrai and Paris were copying out her text as well as Julian's. A small manuscript by them, Bibliothčque Mazarine 1202, titled 'Colections', finished 23 July 1724, on pages 21-22, gives:

n a certain time while I

pray'd in my Cell, these words were sayd

unto me interiorly by God.

III. Umilta` of Faenza (+1310)

e know a great deal, through historical documents,

through paintings, through sculpture, about Beata Umiltą,

Blessed Humility, of Faenza, who was in turn a wife, mother,

nun, anchoress and abbess, who died in Florence in 1310.

Rosanesa Negusanti was born in Faenza to noble

parents named Elimonte and Richilda in 1226. At fifteen she

was married to Ugolotto Caccianemici, bearing him two sons who

both died following their baptisms. She begged her husband to

make a reciprocal vow of chastity. At first he drowned his

sorrows in fun, then fell ill and consented, becoming himself

a monk, while she became a nun, both of the double Monastery

of St Perpetua, in 1250. Rosanesa thus went from freedom to

unconditional obedience, from an abundance of wealth to

monastic poverty, from marriage to total consecration to God.

She mortified herself by taking on the most humble and servile

jobs. The other Sisters thought this was a passing phase but

the Prior of the two monasteries understood her virtue and

named her anew as 'Humility', Umiltą.

Rosanesa persuades her husband Ugolotto to their

vows of chastity

The nuns would eat in silence, one of their number reading to them from a book. Umiltą, though from a rich and noble family, was illiterate. One day, in fun, the other Sisters asked her to read. She obeyed humbly and from her mouth came words of the highest things, yet none of which were to be found written in the book from which she supposedly read. What she said was,

Umiltą's inspired reading in the refectory, Faenza

Umiltą became ill with cancer of the kidneys, causing a nauseous smell from her rotting flesh. She begged God that, if it were his will, he would not inflict such disturbance upon the nursing Sisters. Immediately the Infirmarian Sister saw that the wound had healed. In her four years at St Perpetua she gained esteem and admiration. She felt the need for more isolation, for the life of a hermit. In the night a mysterious voice whispered,

Umiltą leaves her convent

She came to the island of St Martin where the Clarissan Sister Philippa, a wise and severe woman, opened the door to her and gave her shelter for the night. In the morning the Prior and her uncle Niccolo learned about the locked door and the Psalter left on the wall. They gave permission for Umiltą to live in a secret and sealed room. Prayer and penance, bread and water, and bitter herbs, were to be her life

A Vallombrosan monk of Saint Apollinare was about to have his feet amputated, but desired instead to be brought to Umiltą. She signed his feet with the sign of the cross and he was healed. The Vallombrosans built her a cell next to the church of St Apollinarius, into which she was sealed, and which had a small window looking onto the church through which she could see and receive the Sacrament,

Umiltą's little cell attracted a great company, other young women wishing to imitate her, such that the cells multiplied like those in a beehive and the prayers and psalms could be heard in unity ascending into heaven. We are reminded of the growth of Christina's Priory at Markyate. But the Abbot of Vallombrosa now decided that women could join the Order, and that Umiltą should be their Abbess. Umiltą's pet ferret fled at the news. Umiltą cried at being unsealed from her cell, but obeyed her Abbot, following twelve years of self-imposed imprisonment, stepping out again into the world. In 1266 she was made Abbess of the first Vallombrosan convent for nuns. She was stern with both nuns and priests, insisting that they confess their faults before their deaths or before celebrating Mass, for the sake of their souls. One day the cellarer was given a fish to prepare and, thinking it was only enough for the Abbess, served it to her in a delicious sauce. Umiltą flung it into the midst of the refectory floor. The cellarer retrieved it and found it was miraculously large enough to serve all the Sisters.

Fifteen years later, in 1281, Faenza was torn apart

by the strife between Guelf and Ghibelline and Umiltą's

convent was sacked, though she and her Sisters were respected

by the soldiers, because of her sanctity. It was time to

leave. At first it was planned to move to Venice. But Umiltą

was inspired by St John the Evangelist instead to go to

Florence, even though in 1258 the Guelfs there had decapitated

the Abbot Tesoro of Vallombrosa. She chose to go to make peace

between the warring factions. She arrived in the midst of the

Peace of the Cardinal Latino, when Guelf and Ghibelline kissed

and made up for their bitter bloodshed. In that year Dante

Alighieri was seventeen and writing his early sonnets.

Umiltą building her convent, Florence

Umiltą herself gathered the stones, loading them

onto a donkey, to begin building her monastery dedicated to St

John the Evangelist in Florence. One day, while she was doing

so, a nurse brought to her the dead child who was her charge.

Umiltą took the boy into a nearby shrine and laid the cadaver

at the feet of the image of St John the Evangelist, then with

a candle made the sign of the cross over the child, who

miraculously opened his eyes. The convent was founded in 1282.

Umiltą wanted that convent to be simple and poor. The

Florentine authorities decided otherwise and it was

constructed according to the design of Giovanni, son of

Niccolo Pisano, and consecrated in 1297, amidst the building

of Santa Croce, begun, 1295, Santa Maria del Fiore, begun

1296, and the Palazzo della Signoria, begun 1298.

Umiltą resurrecting the dead child

Umiltą became extremely ill with a fever one August and implored her Sisters for ice, telling them to go to the well to fetch it. They found the dry well full of ice. Their obedience had taught them charity. The well today is in the Fortezza da Basso. Another time, when she was too tired to go further on foot in the Appenines a horseman took her up onto his gentle horse, comforting her almost more by his heavenly words. Another time she and her Sisters on such a journey found they could not eat the brown bread given them, when suddenly there appeared the whitest of bread for them to eat. Two women hermits had almost decided to give up their solitude, when they dreamed of Umiltą, who then visited them in reality, and whom they recognised. A knight living near Santa Felicitą in Florence was troubled about his worldly affairs and sought advice from Umiltą. Who told him that that Thursday was to be the last day of his life. Which it turned out to be.

Her Sermons are magnificent. In Sermon II she says it is the divine word which speaks, not coming from her, but from the Father and the highest God, who gives to each as much as he desires. Secretly he has taught her with questions and answers, speaking within her, but now she speaks to us with external words. The Spirit himself had taught her in silence. And she now pronounces aloud to us his divine words which she had heard. Beware therefore that you do not receive this emptily, what her tongue is moved to say, for it is moved by the Spirit. She says in Sermon III that she marvels and fears about these things which rise up within her, which she dares to write and say; for they are not in any book, nor taught to her by any human science; only the Spirit of God speaks within her, opening her mouth with these words which she must say.

And in another Sermon she says,

Umiltą's Funeral, Florence

She was buried in a tomb at the right of the altar

dedicated to St John the Evangelist. A Vallombrosan monk was

healed of a crippled arm that had prevented him from

celebrating Mass. A woman who for five years had been

tormented with an illness that prevented her from speaking or

swallowing was healed. Another woman with a stomach tumor was

likewise healed. The tomb was observed to be covered with oil,

and though it was cleaned, continued that way, the monks

raising the slab and finding the body of the saint incorrupt.

This was checked again, 11 June, 1311, by Antonio degli Orsi,

Bishop of Florence (whose own tomb, by Tino da Camaino, is in

the Duomo) and other witnesses.

Pietro Lorenzetti, after 1313, painted these scenes

of the life of the saint, showing her at its centre in her

habit and veil, all of which is surmounted by the 'vile'

sheepskin cap she was known to wear in her lifetime, and where

she is shown holding forth her book and her flail, Orcagna

similarly sculpting her so. Lorenzetti's polyptych is now

partly in the Uffizi, partly in the Gemaldegalerie in Berlin.

Orcagna's statue is now in the baptistry of the church of San

Michele at San Salvi. Santa Umiltą's large body now rests at

Bagno a Ripoli. 1 March, 1721, she was declared 'Beata

Umiltą', 4 March 1948, Saint Humility. In 1534, the Medicis

had the convent move to San Salvi, near the Campo di Marte.

Later still, in 1815, the authorities suppressed that convent,

the Sisters taking refuge finally, in 1972, with the body of

their Saint in Bagno a Ripoli, whom I have seen there.

Orcagna, La Beata Umiltą

IV. Margaret Kirkeby (+1405?), Margaret Heslyngton (+ after 1435), Emma Stapleton (+1442)

et us return to women contemplatives in England. It

is possible to trace several in connection with Julian of

Norwich's Showing of Love. The earliest surviving

manuscript of that text, the British Library's Amherst

Manuscript, is a florilegium compiled by a male Carthusian for

a female anchorite, by Richard Misyn for Margaret Heslyngton.

The manuscript opens with his translations from Latin into

English of the Yorkshire Hermit Richard Rolle's texts, De

Emendatio Vitae and Incendium Amoris, written

for Margaret Kirkeby, a Cistercian nun at Hampole, then an

Anchoress at Layton, and for another woman contemplative. The

Amherst's colophon to De Emendatio Vitae gives

she said.

Margaret, of the le Boteler family, had been a Cistercian nun at Hampole, had had a seizure, leaving her unable to speak or move, Rolle helping her by holding her head on his shoulder through the window of the anchorhold during a second attack, and promising she would have no more while he lived. On having a third attack, when a recluse a great distance away, at Layton, she sent a messenger to Hampole who found at those moments, on September 29, 1349, Rolle had died, perhaps of the plague. Later, she returned to be enclosed at Ainderby, near Hampole, eventually moving into Rolle's own cell where she died about 1405.

A further such pairing is with Master Alan of Lynn, O.Carm., indicer to Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes /Oxford, Lincoln College, Lat. 69./, Margery Kempe's great friend and director. She speaks of him as 'A worschepful doctour of dyuynite whych hygth Maysyr Aleyn, a Whyte Frer', that is a Carmelite. So also was William Southfield, O.Carm., a White Friar, a Carmelite, who was visited by Margery in Norwich at the same time she encountered Julian in her Anchorhold there.

V. Birgitta of Sweden and Chiara Gambacorta

irgitta of Sweden was the mother of eight children,

an indefatigable pilgrim, who when left a widow journeyed to

Rome for the Jubilee Year of 1300. There she found lodging in

a Cardinal's Palace with a window, a hagioscope looking upon

the altar of San Lorenzo in Damaso, where she would pray and

write. This period of intense anachoritic contemplation

prompted her composition of the Sermo Angelicus, the

dictation to her of the Offices for the nuns to recite of the

Brigittine Order she founded. Later, she was evicted from that

palace and moved to that of Francesca Papazuri in the Piazza

Farnese.

In Birgitta's seventieth year, when dying, she journeyed to Jerusalem and Bethlehem on pilgrimage, writing every day about her visions, her prophecies. She was accompanied on that pilgrimage by the ruler of Pisa, Pietro Gambacorti, and by Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jačn, who had become her spiritual director and the editor of her massive Revelationes . Her models are St Helena and St Jerome's St Paula who similarly journeyed to the Holy Places having visions there.

The Gambacorti had a young daughter, who was friends

with Catherine of Siena and who insisted, despite her parents'

opposition, on becoming a Dominican nun, taking the name in

religion of Chiara. Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jačn, who was

both Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena's spiritual

director, strongly supported Chiara Gambacorta and gave her a

copy of the Revelationes. She succeeded in founding a

monastery in Pisa, living a contemplative life, and she filled

her convent with paintings about St Catherine of Siena and St

Birgitta of Sweden. Especially these paintings dwell on the

scenes of St Birgitta in the act of contemplation and in

contemplative writing. The cells of self knowledge of Saints

Catherine and Birgitta become her own. Today, her tiny body,

like St Umilta`'s large one at Bagni a Ripoli, lies in a glass

coffin beneath the altar of her convent's church in Pisa.

ulian's context, even if only gauged from the

manuscripts containing her work, is fairly and squarely in the

midst of such contemplative 'cells of self-knowledge'.

Julian in the Westminster Manuscript, which seems to replicate the earliest version of her Showing of Love , states it is

gooste. we shulde knowe them.

bothe in oon. whether we be

stered to knowe god. or our

selfe

soule. it ar bothe good &

trewe.

God is nerer to vs. žan owre

owne soule. for he is grounde

in whom oure soule stondyth.

and he is mene žat kepith že

substance & že sensualyte

toge=

der, so žat it shall neuer

depart.

for oure soule syttith in god.

in

verey reste. and oure/ soule

stan= /P118v

dith in god in sure strength.

&

oure soule is kyndely rooted

in

god. in endelesse loue. &

žerfore

yf we wyll haue knowynge

of oure soule. & communyng

& da=]

God is nearer to us than our own soul, for he is ground in whom our soul stands, and he is the means that keeps the substance and the sensuality together so that it shall never depart.

liance žer with: It behouyth

to seke into oure lord god in

whom it is enclosyd. And an=

/P118v.10

nentis oure substance it may

ryghtfully be called our

soule.

and anentis our sensualite it

may ryghtfull be called ou

soule. and žat is by že onyng

žat it hath in god. That wu=

/A112.15

shypfull cite žat our lord

ihesu

syttith in. it is our

sensualite.

in whiche he is enclosed. and

our kyndely substance is

beclo=

syd in ihesu criste. wt že

blessed

soule of criste syttyng in

reste

in že godhed. And I sawe ful

surely žat it behouyth nedis]

And then our substance may rightfully be called our soul, and then our sensuality may rightfully be called our soul, and that is by the oneing that it has in God. That worshipful city

žat/ we shall be in longynge /P119

and in penance. into že tyme

žt we be led so depe in to god

žat we may verely & truely

know oure owne soule. And

sothly I saw žat in to thys

high depenes oure lorde hym

selfe ledith vs in že same

loue

žat he made vs. and in že same

loue žat he bought vs. bi his

mercy & grace žrough

vertue

of his blessed passion. And

not wtstondyng all žis we

may neuer comme to the full

knowyng of god. tyll we first

know clerely oure owne soule.

ffor into že tyme žt it be in

the]

ffull myghtis we may not be

all full holy.]

full strength we may not be all

fully holy.

Julian's editor, who is likely Cardinal Adam Easton, the Norwich Benedictine and colleague of Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jačn, director of Birgitta of Sweden, Catherine of Siena and Chiara Gambacorta, describes the contents of the Forty-Sixth Chapter of the Long Text:

And therefore it must needs be that the nearer we are to our bliss, the more we shall long, and that both by nature and by grace.

We recall how Julian's texts oscillate between Annunciation and Crucifixion, mirroring the 'Book of Life of Christ' within her own 'Book of Julian of Norwich', as Angela of Foligno had counselled we ourselves do. Julian's anchorhold may mirror less the Crucifixion than it does the knitting and weaving of the life of Christ within herself, as in Psalm 139, within her body, her mind, her soul /Angelo of Foligno, Instructions XXII: pp. 293-299, XXXIV: p. 302/ , Julian's anchorhold becoming like that cave at Bethlehem (meaning House of Bread) where Christ was born, that cave at Bethlehem where Paula, Eustochium and Jerome laboured anew to give birth to the Word as the Biblia Vulgata, in their Latin tongue, the caves at Bethlehem to which St Birgitta of Sweden, Margery Kempe of Lynn and John Paul II of Rome, journeyed on their pilgrimages. In this Norwich anchorhold Julian labours in her English tongue to similarly give birth to the Word as prophecy of ourselves and God. But she does so in a pilgrimage within, not journeying to distant shrines.

Turino Vanni, Birgitta's

Vision at Bethlehem . Commissioned by Chiara Gambacorta for her convent of

San Domenico, now in Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa.

VII. Francesca Romana (+1440)

rancesca Romana in the following century, a married

woman with children, founded an order of oblates, creating for

them a monastery, her own cell by the chapel, where later

where frescoed horrendous scenes of the temptations that

beseiged her in prayer. Yet she was able to emerge from these

images of terror, capable of miracles of healing to all those

about her.

See Santa Francesca Romana

and the Torre de' Specchi, Trauma

and Healing: Santa Francesca Romana General/Contemplative/Scholar

These Christian women underwent something similar to

a Shaman's Spirit Quest, or a Freudian analyst's

psychoanalysis. They withdrew to learn themselves and God,

like Mary pondering on all these things in her heart; then,

when the world sought them out as divine prophets and

messianic healers, they were capable of the tasks laid upon

them, for instance advising a Margery Kempe to undertake her

pilgrimage to the Holy Land and the writing of a book about it

as therapy for what ailed her.

ut in 1534 storm clouds were gathering, due to

Elizabeth Barton of Kent's writing a 'greate boke' of Revelations

modeled on those of St Birgitta of Sweden and St Catherine of

Siena, made available to her at Syon Abbey. Her spiritual

director was Dr Edward Bocking, a Canterbury Benedictine.

Already Robert Redman had printed a pamphlet on Elizabeth

Barton's miraculous cure from an illness in Kent. Then 'Thomas

Laurence of Canturbury being regester to the Archidecon of

Canturbury, at the instance and desyre of the seid Edwarde

Bockyng wrott a greate boke of the seid falce and feyned

myracles and revelations of the seid Elizabeth in a fayre

hande redy to be a copye to the prynter when the seid booke

shulde be put to stampe', and that book was printed in seven

hundred copies by John Skot in 1530, one copy even reaching

Tyndale in exile in Antwerp.

Two women, Marguerite Porete, in 1310, Elizabeth Barton, in 1534, were both executed for their theological books, the first perhaps influencing Julian, and with her text in the earliest extant manuscript, the Amherst, with ties to Syon Abbey, the second woman certainly influenced by Birgitta of Sweden, Catherine of Siena and likely also by Julian of Norwich, whose manuscripts, and in the case of Catharina, the printed book, The Orcherd of Syon, were present at Syon Abbey in English versions where she worked on her 'greate boke' of Revelations. The encouragement by the Canterbury Benedictine, Dr Edward Bocking, of the Maid of Kent, Elizabeth Barton, was modelled on that of Magister Mathias and Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jaen collaborating with Birgitta of Sweden on her Revelationes , and could have also been drawn from the Norwich Benedictine, Cardinal Adam Easton, collaborating with the Anchoress, Dame Julian of Norwich, on her Showing of Love, and from the learned Carmelite Doctor of Theology, Adam Hemlyngton, and the Anchoress, Dame Emma Stapleton of Norwich, /Ann K. Warren, Anchorites and Their Patrons in Medieval England (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 213-214./ even shown in the more homely version of the various scribes assisting in the writing of The Book of Margery Kempe in nearby Lynn.

Indeed we need to look at a series of books, all of which are couched about with prefaces and/or colophons, with editorial voices as well as authorial ones, Jerome enveloping Paula and Eustochium in their Bethelehem cave with careful prefaces and epistles, Gregory writing the Dialogue in which we hear the voices of Scholastica and Benedict dialogue, the Benedictine hagiographer of the Vita of Christina of Markyate, Cardinal Jacques de Vitry's hagiography of the Beguine Marie d'Oignes, Fra Arnaldo's Memorials of the Book of Angela of Foligno , Marguerite Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls, The Cloud of Unknowing's colophon likely to a contemplative woman of 24, knowing no Latin, Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes and its Epistola Solitarii penned by Alfonso of Jačn, Catherine of Siena's Dialogo, dictated to her male disciples, Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love in the Sloane Manuscripts with chapter headings and colophon likely penned by Alfonso's colleague, Cardinal Adam Easton, O.S.B., the Book of Margery Kempe , whose second scribe is Alan of Lynn, O.Carm., indexer of Birgitta's Revelationes, the lost Revelations of Elizabeth Barton, organized by Dr Edward Bocking, O.S.B. Women become authors of and in their enclosed lives through enclosure within men's prefaces, epistles, colophons. Men and women together build cells of self-knowledge, within both silence and in dialogue.

For there are so

many echoes between the writings of these different women,

from the twelfth- through the sixteenth centuries, that one

queries whether this is the result of inner contemplation,

within one's cell of self knowledge, or whether they have been

told of the contents of their predecessors' books. Are we

dealing with spiritual resemblances, or intellectual

borrowings? As a scholar I continue to sift the evidence,

checking as to what manuscripts of what texts are available

where. As a contemplative I find myself responding to these

texts in their own right, as cells not only of their

knowledge, but of ours, that paradox in which a cell becomes

the boundless universe, and more, God's presence.

Mount Grace Priory Charterhouse

Bibliography

Acta Sanctorum. May V, 22 May, 203-222. [Umilta` da Faenza.]

Aelred of Rievaulx. De Institutione Inclusarum. Ed. John Ayto and Alexandra Barratt. London: Oxford University Press, 1984. Early English Text Society 287.

Angela of Foligno. Complete Works . Trans and Ed. Paul Lachance, O.F.M. Preface. Romana Guarnieri. New York: Paulist Press, 1993.

____________. Latin Text. S.I.S.M.E.L. http://www.sismelfirenze.it/mistica/ita/TestiStrumenti/fullTextAngela.htm

Aston, Margaret. Lollards and Reformers: Images and Literacy in Late Medieval Religion.

Bazire, Joyce and Eric Colledge. The Chastising of God's Children and the Treatise of the Perfection of the Sons of God. Oxford: Blackwell, 1957.

Breve Racconta della Vita Miracoli e Culto di Sant'Umilta Fondatrice della Monache Vallombrosane. Scritto da un Religioso del Medesimo Ordine. Firenze: 1722.

Davidsohn, Robert. Storia di Firenze.

Deanesly, Margaret. The Incendium Amoris of Richard Rolle of Hampole. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1915.

Gilchrist, Roberta and Marilyn Oliva. Religious Women in Medieval East Anglia. Norwich: University of East Anglia, 1993. Studies in East Anglian History 1.

The Book of Margery Kempe , ed. Sanford Brown Meech and Hope Emily Allen. London: Oxford University Press, 1940. EETS 212

Montgomery, Carmichael. 'An Altarpiece of Saint Humility'. The Ecclesiastical Review, 1913.

Nuth, Joan. Wisdom's Daughter: The Theology of Julian of Norwich.

Rolle, Richard. Prose and Verse . Ed. S.J. Ogilvie-Thomson. London: Oxford Unviersity Press, 1988. Early English Text Society, 293.

Salvestrini, Don Otello. Santa Umiltą: Sposa, Madre, Eremita, Monaca. Firenze: Il Consiglio Pastorale della Comunitą parrocchiale di S. Michele a S. Salvi, 1981.

Simonetti, Adele. I Sermoni di Umiltą da Faenza. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo; Firenze: Societą Internazionale per lo Studio del Medioevo Latino (S.I.S.M.E.L ), 1995.

Talbot, Charles H. The Liber Confortorius of Goscelin of St Bertin. Studia Anselmiana37 (1955).

___________. The

Life

of

Christina

of Markyate: A Twelfth-Century Recluse. Oxford: Clarendon

Press: Toronto: Medieval Academy of America, 1997.

Vauchez, André. La Sainteté en Occident aux derniers sičcles du Moyen Age: d'aprés les procés de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques. Rome: Ecole Franēaise de Rome, Palais Farnese, 1981.

Warren, Ann K. Anchorites

and Their Patrons in Medieval England. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1985.

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS

CONTEXTS ©1997-2024

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY || JULIAN

OF NORWICH || SHOWING

OF LOVE || HER TEXTS

|| HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE

AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |