-

Christ to Bishop Hemming,

in St Birgitta, Revelationes I.52

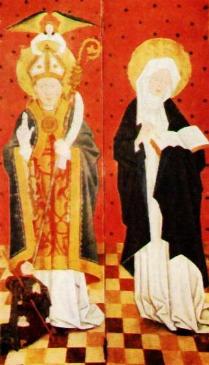

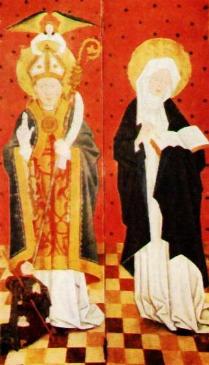

Bishop Hemming and St Birgitta, Urdiala, Finland

Bishop Hemming and St Birgitta, Urdiala, Finland

In the late Middle Ages Finland, then an eastern province of the Swedish Kingdom, was only partially Christianized. The cooperation with the Swedish church was close and most of Finland's high-ranking clergymen came from the Swedish Diocese of Uppsala and the region's written language was Swedish. When Birgitta was still in Sweden - that is, before her journey to Rome in 1349, from which she never returned - Finland was shepherded by the efficient and learned bishop of Åbo, Hemming (from 1338-1366). Hemming came from a well-to-do Swedish family, had close contacts with Swedish nobility, and knew Birgitta well. Birgitta chose him to accompany her confessor, the Cistercian Prior Peter of Alvastra, in a mission to Pope Clement VI at Avignon and to the Kings of England and France.

Bishop Hemming and Prior Peter made their journey between 1346 and 1349. Their mission was to deliver to the Pope Birgitta's Revelation which lamented the decline of the Papacy. This Brigittine Revelation urged the Pope to reform his own lasciviousness, to cease supporting the King of France, and to return the Papal See to Rome. In Birgitta's Revelation Christ spoke directly to Clement:

For several decades the Brigittine Abbey of Nådendal was vital for Finnish religious, cultural and economic life. The Abbey was favoured by the nobility and gentry, whose generous donations helped Nådendal compete even against the nearby Cathedral of Åbo (in Finnish, 'Turku'), and that city's Dominican convent dedicated to Saint Olaf. The annual fairs in Nådendal helped the village's economy and merchants greatly profited from the pilgrims who came. The spiritual life of the cloistered nuns of Nådendal focused on contemplation and prayer, but they had a reputation also for their skilful handwork. Their lace products were especially famous. In the Abbey church the priest-monks gave sermons in both Swedish and Finnish, and they also had charge of the religious education of the nuns. The Abbey included the first-known Finnish author, Jons Budde (+ 1491), who translated saints' legends and the Books of Ruth and Esther into Swedish for the nuns' daily readings.

At the end of the fifteenth century Birgitta's cult blossomed also in other regions of Finland. Her feast day, 7 October, was given a solemn celebration. Birgitta and the Norwegian warrior king, Saint Olaf (+1030), were viewed as regional saints in Finland, alongside the sole canonized Finnish saint, the missionary Bishop Henrik (+1156). St Birgitta's popularity is seen in numerous church dedications. Several mural paintings and wooden statues of her survive from the fifteenth century, in which Birgitta is usually depicted with her characteristic emblem, the book, symbol of the Revelationes she received and which she then wrote.

Santa Birgitta ora pro nobis . 'Saint Birgitta, pray for us'. This inscription can still be seen under a well preserved mural painting of Birgitta in the Church of Parainen (1486). People asked Birgitta for intercessory prayer at the time when the Finnish region was entering exceptionally hard times. Throughout the Middle Ages, Finland had remained on the fringes of the Swedish Kingdom and consequently in poverty. At the end of the fifteenth century that poverty was aggravated by the Great Russian War, by very harsh winters, by famine and by epidemics of plague. The Abbey of Nådendal also suffered and in the 1508 Plague no less than thirty-six brothers and sisters died. The Finnish Brigittine Abbey never recovered its former glory after the loss of at least half its members. Its history as a Catholic Abbey then ended with the Lutheran Reforms executed by King Gustaf Wasa. After 1544, monastic life was prohibited and the property of Catholic religious houses was confiscated.

St Birgitta, Revelationes V, The Book of the

Questions, Doubting Monk (Magister Mathias) on Ladder,

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1500. Helsinki University Library

he Lutheran Reform in Finland was carried out with

great thoroughness. Today about ninety per cent of Finns

belong to the Finnish Lutheran Church. With over four million

members it ranks as the world's third largest Lutheran Church.

In the decades of the Reformation, and in the following

centuries, the cult of the saints was banned. In modern times,

St Birgitta is, however, remembered as a major personage in

medieval Scandinavia, and she is greatly honoured as part of

Scandinavia's religious heritage.

he Lutheran Reform in Finland was carried out with

great thoroughness. Today about ninety per cent of Finns

belong to the Finnish Lutheran Church. With over four million

members it ranks as the world's third largest Lutheran Church.

In the decades of the Reformation, and in the following

centuries, the cult of the saints was banned. In modern times,

St Birgitta is, however, remembered as a major personage in

medieval Scandinavia, and she is greatly honoured as part of

Scandinavia's religious heritage.

Birgitta has also left many marks on Finnish secular culture and folklore. In medieval times children were given the names of the saints and such popular Finnish names as Piritta, Pirjo and Pirkko derive from Birgitta. Finland has kept the custom of celebrating namedays. 7 October, Birgitta's Feast Day, is also the nameday for her namesakes.

In folklore one finds many elements that have been

adapted from high culture, but which are interpreted in

down-to-earth fashion. Several Finnish proverbs were inspired

by Birgitta's Legend. For example, the Finnish word for

'ladybird' (English), 'lady bug' (American), leppapirkko,

reveals a combination of both pagan and Christian cultures.

'Ladybirds' in medieval Finland were seen as messengers in the

animal world who carried people's wishes to the gods, but in

the Christian era people learned to pray for the intercession

of the saints. Common people then fused the traditions by

giving the name of a popular saint, Birgitta, to their former

animal messenger.

n our times, St Birgitta has inspired historians and

artists. A celebrated Finnish author, Eila Pennanen, wrote a

historical novel on the saint. This book, Pyha Birgitta

(1955), drew a picture of a woman who, as a visionary, was a

saint, but who, also, in her maternal emotions, in her

occasional weariness, and in her overwhelmingly strong will,

had the feelings of an ordinary human being. Eila Pennamen's

vivid and accurate descriptions of late medieval life and its

religious culture reminds the reader of another famous author

of historical novels, the Norwegian Nobel Prize winner, Sigrid

Undset.

n our times, St Birgitta has inspired historians and

artists. A celebrated Finnish author, Eila Pennanen, wrote a

historical novel on the saint. This book, Pyha Birgitta

(1955), drew a picture of a woman who, as a visionary, was a

saint, but who, also, in her maternal emotions, in her

occasional weariness, and in her overwhelmingly strong will,

had the feelings of an ordinary human being. Eila Pennamen's

vivid and accurate descriptions of late medieval life and its

religious culture reminds the reader of another famous author

of historical novels, the Norwegian Nobel Prize winner, Sigrid

Undset.

St Birgitta has also been studied by Finnish historians, among whom, beyond compare, was Birgit Klockars. Birgit Klockars' books studied St Birgitta's social milieu, the Saint's literary learning, and the life of the Nådendal Abbey. These books are still only published in Swedish, giving English summaries at their conclusion, but it is hoped that soon the English-speaking world may have more access to them.

St Birgitta's Order has now returned to Finland.

Since 1986 there has been a Brigittine house in Turku and, in

1996, a second house was established in Helsinki. These houses

belong to the Order's new branch, founded in 1911 by the

Swedish Sister Elisabeth Hesselblad. The Finnish Brigittine

houses are small, totalling only fifteen Sisters. But with

members from Italy, Mexico, India and England they add a

further international flavour to Finland's already

multicultural Catholic church. Birgitta valued the

contemplative life and her Order follows her model. In recent

years, short contemplative retreats have been revived also in

the Finnish Lutheran church. Every October there is a retreat

in Naantali (Nådendal) which honours the saint by naming the

event as Birgitanpaivat, 'St Birgitta's Weekend'.

Bibliography

Birger Gregersson and Thomas Gascoigne. The Life of St Birgitta. Trans. Julia Bolton Holloway. Toronto: Peregrina, 1991.

Birgitta of Sweden: Life and Selected Revelations. Ed. Marguerite Tjader Harris, Albert Ryle Kezel, and Tore Nyberg. New York: Paulist Press, 1990.

Johannes Jørgensen. Saint Bridget of Sweden. Trans. Ingeborg Lund. 2 vols. London: Longmans, Green, 1954.

Julia Bolton Holloway. Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations, Translated from the Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Newburyport: Focus, 1992.

Birgit Klockars, Biskop Hemming av Åbo. Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland; København: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1960.

_______________. I Nadens dal Klosterfolk och andra, c. 1440-1590. Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1979.

_______________. Birgitta och Böckerna. En undersökning av den heliga Birgittas kallor. Stockholm: Alqvist & Wiksell, 1966.

Christian Krötzl. Pilger, Mirakel und Alltag. Formen des Verhaltens im skandinavischen Mittelalter. Tampere: Studia Historia 46, Societas Historica Finlandiae, 1994.

Aare Lantinen, 'Nådendals placering i den sociala miljon i Åbo stift'. In Birgitta, hendes vaerk og hendes klostre i Norden. Ed. Tore Nyberg. Odense: Odense Universitetsförlag, 1991.

Tore Nyberg. Birgittinische Klostergrundungen des Mittelalters. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1965.

Istvan Räcz and Riitta Pylkkänen, Art Treasures of Medieval Finland. Trans. Diana Tullberg and Judy Beesley. New York: Praeger, 1967.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |