THE PASSION IN JULIAN OF NORWICH

SISTER ANNA MARIA REYNOLDS,

CROSS AND PASSION

'

SIMPLE

unlettered creature' - Thus

modestly (and inaccurately!) does the author of Sixteen

Revelations of Divine Love introduce herself in the second

chapter of her book. As students of her writings are realizing

more and more, however, she was neither simple (except in a

purely theological sense) nor unlettered, but a learned woman

endowed with a powerful intellect and rare spiritual gifts. In

this short article I shall concentrate on what Julian has to

say about the Passion of Christ, dealing first with what she

actually 'saw' and then with some of the insights she was

later granted.

SIMPLE

unlettered creature' - Thus

modestly (and inaccurately!) does the author of Sixteen

Revelations of Divine Love introduce herself in the second

chapter of her book. As students of her writings are realizing

more and more, however, she was neither simple (except in a

purely theological sense) nor unlettered, but a learned woman

endowed with a powerful intellect and rare spiritual gifts. In

this short article I shall concentrate on what Julian has to

say about the Passion of Christ, dealing first with what she

actually 'saw' and then with some of the insights she was

later granted.

Julian of Norwich (Norfolk, England) lived in the fourteenth century, from 1342 until 1416 or later. Very little indeed is known of her apart from the few facts she herself mentions in her writings and references to her in a few contemporary wills and in the contemporary Book of Margery Kemp. She was a recluse or anchoress, vowed to a solitary, enclosed life of prayer and contemplation. Her anchorhold was built on the side of St Julian's Church, Norwich. Unfortunately the Church was destroyed early in Worl War II but it has been reconstructed and a replica of Julian's cell is now a shrine and place of pilgrimage.

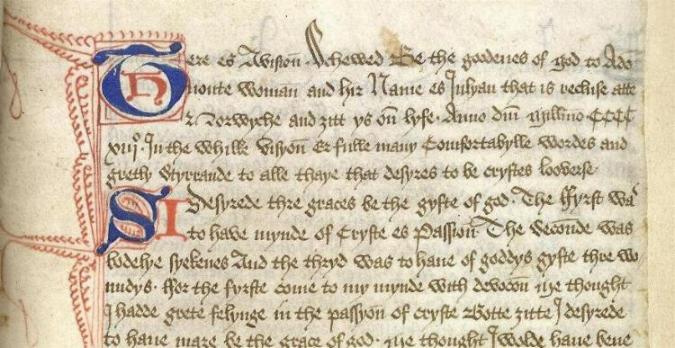

Julian's writings have come down to us in a short form probably written down immediately after the religious experience they describe, and in a greatly expanded version. This longer version incorporates the fruits of twenty years of prayerful pondering by the anchoress on the original showings. The short text exists in only one manuscript, the longer in three complete manuscripts; there are also some extracts. None of the manuscripts is in Julian's hand or contemporary with her. The unique short one is usually dated mid-fifteenth century,

By Permission of the British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97

the oldest of the long texts sixteenth century.

Elizabethan Showing of Love Manuscript, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Anglais 40

From both texts we learn that Julian in her youth had desired from God three special graces:

The first was to have recollection of Christ's Passion. The second was a bodily sickness, and the third was to have, of God's gift, three wounds (125).1She adds that she already has a considerable 'feeling' for the Passion of Christ, but she wished to have a more intense devotion. She wished that she could have been actually present on Calvary to witness Christ's Passion 'which he suffered for me', she adds significantly, so that she in turn could share in his sufferings as did the others who 'loved him' and suffered with him on Calvary. So Julian actually prayed for a 'bodily sight' of Christ in his Passion.

Sir Miles Stapleton, who knew Julian of Norwich, commissioned this manuscript for himself.

The second grace, of a near-mortal bodily sickness, the anchoress desired because she wanted to experience all the pains and pangs of dying as a purification, so that afterwards she would live more entirely for God. The third grace she begged for was to receive three wounds:

the wound of true contrition, the wound of loving compassion, and, and the wound of longing with my will for God (179).The first two favours she asked conditionally - if it were God's will; the third she besought urgently and unconditionally. And she adds:

the two desires which I mentioned first passed from my mind, but the third remained there continaully (ibid).Julian was in her 31st year when, in May 1373, all three graces were granted to her. She was struck down with what appeared to be a mortal illness during which she received the last rites of the Church; as she lay, more dead than alive, trying to keep her dying gaze fixed on the crucifix which the curate had brought and set before her, she recalled her petition for the 'wound of loving compassion' with Christ suffering:

for I wished that his pains might be my pains, with compassion which would lead to longing for God (180).It was at this point that the showings began, sixteen in all. Fifteen were shown continuously from about 4 o'clock in the morning until 3 o'clock in the afternoon. The sixteenth showing took place on the following night.

The first, second, fourth, fifth, eight and ninth of these showings were directly concerned with the Passion of Christ. They are described by Julian with great realism using homely concrete images drawn from daily life as well as vivid detail inspired by contemporary stained glass windows and other art forms.

The series began when the dying woman saw the crucifix on which she was gazing come alive, as it were:

Suddenly I saw the red blood running down from under the crown, hot and flowing freely and copiously, a living stream, just as it was at the time when the crown of thorns was pressed on his blessed head (181).The second showing concentrated on the Sacred Face of Our Lord:

I looked with bodily vision into the face of the crucifix hung before me, in which I saw a part of Christ's Passion: contempt, foul spitting, buffeting, and many long-drawn pains, more than I can tell; and his colour often changed. At one time I saw how half his face, beginning at the ear, became covered with dried blood, until it was caked to the middle of his face, and then the other side was caked in the same fashion (193).The fourth showing depicted the scourging. Julian tells that, as she gazed,

the fair skin was deeply broken into the tender flesh, through the vicious blows delivered all over the lovely body. The hot blood ran out so plentifully that neither skin nor wounds could be seen, but everything seemed to be blood (199).In the eighth showing Julian sees Christ almost at the point of death. The picture, though in part derived from medieval paintings and sculptures, is nevertheless intensely personal and poignant:

I saw his sweet face as it were dry and bloodless with the pallor of dying, and then deadly pale, languishing, and then the pallor turning blue, and then the blue turning brown, as took took more hold on his flesh. For his Passion appeared to me most vividly in his blessed face, and especially in his lips. I saw there what had become of these four colours, which had appeared to me before as fresh and ruddy, vital and beautiful. This was a painful change to watch, this deep dying, and his nose shrivelled and dried as I saw; and the sweet body turned brown and black (206).In deep grief Julian beholds the dying Christ, waiting in agony for the moment of his death. But as she thinks this moment has come, there is a dramatic change. In the ninth vision she writes:

Suddenly, as I looked at the same cross, he changed to an appearance of joy. The change in his blessed countenance changed mine, and I was as glad and joyful as I could possibly be. And then cheerfully our Lord suggested to my mind: 'Where is now any instant of your pain or of your grief?' And I was very joyful (215).She was at that instant completely cured of her serious illness.

The corporeal visions described above were the initial answer to Julian's petition for a 'bodily sight0 of Christ in his Passion, but as she prayerfully pondered over them in the years that followed she received precious insights into their significance - insights so enlightening and comforting that she felt an imperious need to share them with all who seek to love God without reserve.

First and foremost the anchoress learned that Christ has suffered and died for her personally. She realized that she could apply to herself with perfect truth the saying of St Paul: 'He loved me and delivered himself up for me (Galatians 2.20). She writes:

Then our good Lord put a question to me: 'Are you well satisfied that I suffered for you?' I said: 'Yes, good Lord, all my thanks to you; yes, good Lord, blessed may you be'. Then Jesus our good Lord said: 'If you are satisfied, I am satisfied. It is a joy, a bliss, an endless delight to me that ever I suffered my Passion for you; and if I could suffer more, I would suffer more' (2166)Moreover, Julian was taught that all three persons of the Trinity were involved in the mystery of Christ's Passion. In her account of the very first showing she states:

Suddenly the Trinity filled my heart full of the greatest joy, and I understood that it will be so in heaven without end to all who will come there. For the Trinity is God, God is the Trinity. The Trinity is our maker, the Trinity is our protector, the Trinity is our everlasting lover, the Trinity is our endless joy and our bliss, by our Lord Jesus Christ and in our Lord Jesus Christ. And this was revealed in the first vision and in them all, for where Jesus appears the blessed Trinity is understood, as I saw it (181).Later, she is even more explicit:

All the Trinity worked in Christ's Passion, administering abundant virtues and plentiful grace to us by him; but only the Virgin's son suffered, in which all the blessed Trinity rejoice (219).Man, too, is present 'where Jesus appears', since for Julian humanity is comprehended in the second Person of the Trinity: 'When God looks upon humanity he sees the life of Christ', as Brant Pelphrey expresses it.2 In the crucifixion Julian sees God as absolutely at one with humanity, undergoing the worst human suffering at the hands of his fellowmen, while at the same time demonstrating his perfect union with the Father. The anchoress in her account of Christ's sufferings emphasizes the total identity which he assumes with us as creatures. Christ did not escape suffering because he was God - on the contrary, as she puts it:

the union in him of the divinity gave strangth to his humanity to suffer more than all men could (213).She goes on:

And he suffered for the sins of every man who will be saved; and he saw and he sorrowed for every man's sorrow, desolation and anguish, in his compassion and love (213).Julian saw what Isaiah had foretold centuries before:

And yet ours were the sufferings he bore,And all this was for love of us, she adds, echoing Philippians 2.6-11:

ours the sorrows he carried.

But we, we though of him as someone punished,

struck by God and brought low.

Yet he was pierced through for our faults,

crushed for our sins.

On him lies the punishment that brings us peace,

And through his wounds we are healed (Isaiah 53.4-5)

I saw that the love in him which he has for our souls was so strong that he willingly chose suffering with a great desire, and suffered it meekly with a great joy (214).Mary, our Mother, suffered with and through her Son. Julian stresses the compassion of Mary and refers to it several times:

for Christ and she were so united in love that the greatness of her love was the cause of the greatness of her pain. For in this I saw a substance of natural love which is developed by grace, which his creatures have for him, and this natural love was most perfectly and surpassingly revealed in his sweet mother; for as much as she loved him more than all others, her pain surpassed that of all others. For always, the higher, the stronger, the sweeter that love is, the more sorrow it is to the lover to see the body which he loved in pain (210).Later, the anchoress refers again to our Lady in this context:

For as much as our Lady sorrowed for his pains, so much did he suffer sorrow for her sorrows (213).Julian's visions of Christ's Passion do not, however, end on a note of sorrow but of joy and hope. She writes:

So long as he was capable of suffering, he suffered for us and sorrowed for us. And now he is risen again and is no longer capable of suffering - and yet he suffers with us, as I shall say (214).As she gazed on the Cross, waiting tensely for the moment when Christ would expire, she experienced the joy of the risen Christ:

Suddenly, as I looked at the same cross, he changed to an appearance of joy. The change in his blessed appearance changed mine, and I was as glad and joyful as I could possibly be. And then cheerfully our Lord suggested to my mind: 'Where is now any instant of your pain or of your grief?' And I was very joyful. I understood that we are now on his cross with him in our pains, and in our sufferings we are dying, and with his help and his grace we willingly endure on that same cross until the last moment of life. Suddenly he will change his appearance for us, and we shall be with him in heaven (215).This note of joy is underlined by Julian's realization that by his Passion Christ has ovecome the Devil, a fact she refers to again and again in her writings:

'With this the fiend is overcome'. Our Lord said this to me with references to his blessed Pasion, as he had shown it before. In this he showed a part of the fiend's malice, and all his impotence, because he showed that his Passion is the overcoming of the fiend (201).Towards the end of her book Julian comes back to this saying of our Lord:

. . . just as in the first words which our good Lord revealed, alluding to his blessed Passion: 'With this the fiend is overcome', just so he said in the last words with perfect fidelity, alluding to us all: 'You will not be overcome'. And all this teaching and true strengthening apply generally to all my fellow-Christians, my even-Christians, as is said before, and so is the will of God (315).The anchoress concludes these comments with a passage which has become justly famous:

And these words: 'You will not be overcome' were said very insistently and strongly, for certainty and strength against every tribulation which may come. He did not say: 'You will not be troubled, you will not be belaboured, you will not be disquieted', but he said: 'You will not be overcome'. God wants us to pay attention to these words, and always to be strong in faithful trust, in well-being and in woe, for he loves us and delights in us, and so he wishes us to love him and delight in him, and all will be well (315).And so the showings ended.

Practical woman that Julian was, and full of healthy curiosity, from the very first moment of reflection she kept asking what was our Lord's 'meaning' in making these revelations to her. Christ himself eventually answered her query. The anchoress relates the explanation she was given in an immortal passage which brings her book of revelatins to a close:

And fifteen years after and more, I was answered in spiritual understanding, and it was said: 'What, do you wish to know your Lord's meaning in this thing? Know it well. Love was his meaning. Who reveals it to you? Love. What did he reveal to you? Love. Why does he reveal it to you? For Love. Remain in this and you will know more of the same. But you will never know different, without end'.So, Julian concludes:

I was taught that Love is our Lord's meaning. And I saw very certainly in this and in everything that before God made us he loved us . . . which love was never abated and never will be. And in this love he has done all his works, and in this love he has made all things profitable to us, and in this love our life is everlasting. In our creation we had beginning, but the love in which he created us was in him from without beginning. In this love we have our beginning, and all this shall we see in God without end (342-3).

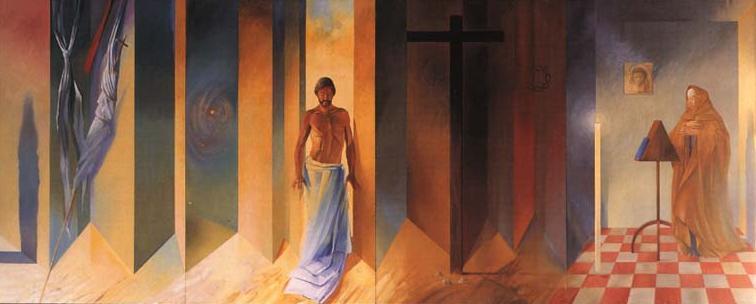

The illustration is taken from the painting of Julian's Showings in St Gabriel's Chapel, Community of All Hallows, Ditchingham, Near Bungay, Suffolk. Painted by the Australian artist, Alan Oldfield, it was earlier exhibited in Norwich Cathedral; photographed, Sister Pamela, C.A.H. © Reproduced by permission of the Community of All Hallows and the Friends of Julian.

Notes

1 Revelations of Divine Love; I have used

the translation by E. Colledge and James Walsh (London and New

York, 1978). References are to pages in this edition.

2 Brant Pelphrey, Love was

his Meaning: The Theology and Mysticism of Julian of Norwich

(Salzburg, 1982), p. 166.

See also:

Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds, C.P., Courtesy and

Homeliness in Julian of Norwich;

Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds, C.P., Some Literary

Influences in Julian of Norwich;

and The Julian Summit

Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever had. During

the war years she was transcribing the extant microfilms with a

microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds University MA and

Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based on her meticulous

work, though they habitually fail to acknowledge her.

Sister Anna Maria

Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever had. During

the war years she was transcribing the extant microfilms with a

microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds University MA and

Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based on her meticulous

work, though they habitually fail to acknowledge her.

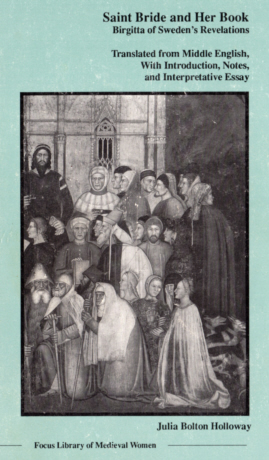

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

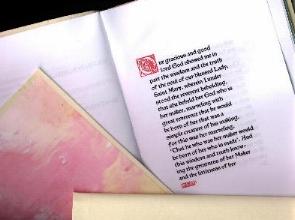

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Three: Divine Love in

Julian of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||