JULIAN OF NORWICH

ON PRAYER

PREFACE

Honouring Sr Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P.,

Editor of Julian of Norwich, Revelations, University of

Leeds Theses, 1947, 1956; and Tony St Quintin, likewise of

Ireland and now Leeds, who directed the typesetting in Notabene

of our Julian edition.

Introduction:

![]() ulian

of

Norwich, and Augustine before her in his Confessions,

obeyed Christ’s words that they should pray to God. These

texts Julian uses, the Shema (Leviticus 19.18, Mark

12.28-31), the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6.5-23, Luke 11.1-4),

the Confessions of St Augustine, the Rule of

St Benedict, the Dialogues of St Gregory, in her Showing

of Love, become all one prayer, a plea, that we love

God and our even-Christian, our neighbour, as ourselves. I

will first discuss the manuscripts, then the six prayers as

one of Julian.

ulian

of

Norwich, and Augustine before her in his Confessions,

obeyed Christ’s words that they should pray to God. These

texts Julian uses, the Shema (Leviticus 19.18, Mark

12.28-31), the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6.5-23, Luke 11.1-4),

the Confessions of St Augustine, the Rule of

St Benedict, the Dialogues of St Gregory, in her Showing

of Love, become all one prayer, a plea, that we love

God and our even-Christian, our neighbour, as ourselves. I

will first discuss the manuscripts, then the six prayers as

one of Julian.

The Manuscripts:

There are three layers to Julian’s text.1

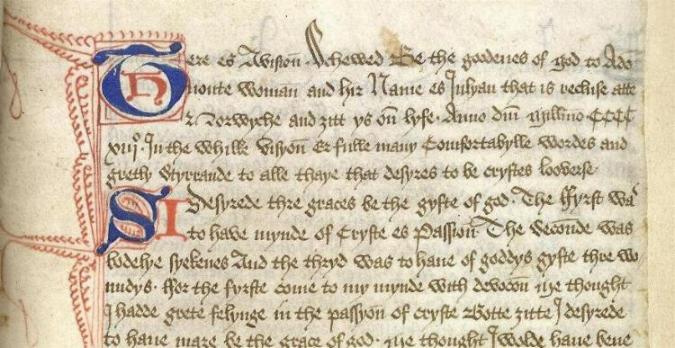

I. Westminster Manuscript, fol. 1

The Westminster Manuscript, containing Walter Hilton

and Julian of Norwich (W), I take to give her initial writing,

when she is 25, before her 1373 death bed vision, and which

dates itself as ‘1368’, though it is written later, by a Syon

Abbey nun circa 1450/1500, in a London dialect.

____

II. Paris Manuscript, fols. 8v-9

I saw her ghostly in bodily lykenes a sim= |

her is nothing that is made, but the |

Julian's Paris and Sloane Manuscripts of the Long Text pad the Westminster version with the 1373 vision, carefully structuring the text, much under the influence of the Revelationes of Birgitta of Sweden, possibly with Cardinal Adam Easton, the Norwich Benedictine as its editor, 1387-1393. It is finished when Julian is 45 or 50. Then both the Westminster Manuscript (W) and the Paris Manuscript (P) were copied out by Brigittine nuns, the first at Syon Abbey under Henry VIII, the second in exile at Mechlin, when Elizabeth I reigned, both manuscripts with careful rulings in preparation for the printing press, but in neither case was their publication permitted. The Paris Manuscript uses rubrication for Christ's words to Julian; other manuscripts employ larger letters. Julian's writings were treasured by English Benedictine nuns, such as Dame Gertrude More, in exile in the seventeenth century, and copy edited by them for the Showing's publication in 1670, with the Sloane Manuscripts, S1 and S2, of which S1 most carefully replicates Julian’s original Norwich dialect. Beside the Sloane Manuscripts, there are also excerpts from Julian in booklets on contemplative prayer written out by Dames Margaret Gascoigne, Barbara Constable and Bridget More, English Benedictines at Cambrai under the spiritual direction of Dom Augustine Baker, O.S.B. For it became their tradition to copy out texts useful for prayer, to be found in their cells at their deaths and passed on to new generations of sisters. These booklets and fascicles are now in French archives and libraries and at Colwich Abbey, though many more were lost at the Revolution from Cambrai's contemplative library built up by Dame Catherine Gascoigne, including Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love manuscript in her own dialect and her own hand.

____

III. Amherst Manuscript, fol. 97

By Permission of the British

Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97

In 1413, Julian was constrained to censor herself, removing from her text her Biblical translations, made directly from the Hebrew into English, under Archbishop Chancellor Arundel’s 1407-1409 Constitutions against the Lollards, and she dictated her final Short Text, in the Amherst Manuscript (A), at 70. There are corrections made in a different hand, possibly Julian's own, than that of the Lincolnshire scribe writing out this revised text of the Showing of Love. Her last words in it, using the Lollard term and Wyclif's theology, speak of her 'Evencristenn'. That final version commences a manuscript collection assembled by a Carmelite, likely for Lady Emma Stapleton, the Carmelite anchoress in Norwich.2 All three versions of Julian's Showing of Love are treatises on prayer.{ere es Avisioun. Schewed Be the goodenes of god to Ade=

uoute woman and hir Name es Julyan that is recluse atte

Norwyche and 3itt. ys oun lyfe. Anno domini millesimo. CCCC.

xiij° [1413]. In the whilk visyoun Er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and

gretly Styrrande to alle thaye that desyres to be crystes looverse.

IV & V: Besides these versions of the Showing of Love is a manuscript in Norwich Castle (N), written by an anchoress for an anchoress in the Norwich dialect,3

IV. Norwich

Castle Manuscript, fol. 1

|

Apistle of sent Jerom sent to a

mayde demetri ade. that hadde uowed chastite to our lorde ihesu criste~ { |

which may have been compiled also by Julian, including such comments as

Thenk on seint Cecile & doo as sche dede. for sche haar euere in herte in here brest woordis of the gospel. and of holy writ and neither nyght ne day sche stynted fro prayeris & fro god dis woordis(fols. 26v-27), together with a fine treatise on the Lord’s Prayer; and another manuscript, now at Lambeth Palace (L),4 from which I give an example on the handout,

{this one similarly written by a Syon Abbey Sister who may be copying a Julian text of prayer.4o I am here afore

the my lord god

as on frend afore a nother

desyring that thy yn

fynyte charite may

drawe me on to the.

And so to one and

knytte me to thy loue

that I neuer be depart

yd no separat fro the,

All these manuscripts tell us that their contexts

are either monastic or anachoritic, and for women and, all but

one, were even written by women scribes living intense lives

of prayer. The influences upon these texts are the Psalms and

the Gospel; they are Benedictine, Augustinian, Carmelite and

Brigittine, all of which Orders lived prayer in lectio

divina of the Bible and chanting the Psalms seven times

daily (W79v.14-17).

__________

The Six Prayers:

I. 'O Sapientia'

|

{ |

Julian’s Showing in the Westminster Manuscript, and which is repeated in all the other versions, though not at their beginning, opens with God showing to Julian, Mary in prayer to her as-yet-unborn Son, singing to him the Advent Antiphon, ‘O Sapientia’ [W72v, P8v, A99v.7]. Julian centres this vision on Mary’s humility, Christ’s Incarnation, the ‘before beginning’, going backwards through time. In doing so she partly reflects on the obstetric Psalm 139.9, which she will use again with the passage where Jonah quotes that Psalm in the belly of the whale, 2.5 [P20v.20]. Later Julian will join Christ and Mary as one [P122-122v (ffor in that same tyme that god knytt hym to oure body in the meydens wombe he toke oure sensuall soule in whych takyng he vs all havyng beclosyd in hym. he onyed it to oure substance. In whych oonyng he was perfit man. for crist havyng knytt in hym all man that shall be savyd is perfete man. Thus oure lady is oure moder in whome we be all beclosyd and of hyr borne in crist. for she that is moder of our savyoure is mother of all that ben savuyd in our sauyour. And oure savyoure is oure very moder in whome we be endlesly borne and nevyr shall come out of hym)]. She will garb her Lord in Aaron’s blue, seated on the earth, in the iconography of the ‘Madonna in Humility’.5 She tells us Christ is our Mother Holicherche [P61v]. We contemplate Julian contemplating Mary contemplating Christ, who is the Word, who is her Showing, tenting within us, ‘nerer to us. than owre owne soule’ [W101, P118.14]. She tells us that prayer is a 'lesson of love' [P13v, P43v (And loue was without begynnyng. is and ever shall be without ende)] while the devil loves the anxious despairing bidding of beads, the making of many futile means in prayer [P146v.16-147.2]. She advocates that prayer be 'interly inwardly' [P73-80v], in which God is our ground, becomes as our mother, we his heir, oned in his womb, he in ours, in the 'city of our soul'. She will end with 'and love was his menyng' [P173v].

II. Gregory on Benedict in Prayer: Space

Gregory, in the Dialogus II.xxxvi, following

upon the narration about Scholastica and Benedict spending the

whole night, like Monica and Augustine, in contemplative

prayer, tells of Benedict in prayer on a tower being witnessed

in such a way that the whole cosmos becomes shrunk into one

sunbeam, Gregory then explaining to Peter that the whole world

seems to be small because it is seen in the presence of its

Creator. Julian takes this image (it is in all three

versions), and she applies it to her vision of the whole

cosmos held in the palm, not of God’s hand, but of her own, as

the quantity of a hazelnut [W74, P9, 13v-14, 16v.17, A99.17]:

|

And in this he shewed me a lytil |

Then she recurs to it again and again in her texts [W80 (ffor of all thyng the beholdeng & the lovyng of the maker causith the soule to seme leste in his owne sight. and most fyllith it with reuerent dred and true meknes. and wt plente of charite to his euencristen), P139v.18-20 (and that is that a creatur see the lord meruelous great. and herself mervelous litle)], A100.16 (Botte the cause why it schewed so lytille to my syght was for I sawe itte in the presence of hym that es makere)].

III. The Gospels' Lord’s Prayer, Paul's Epistle to the Romans, and Benedict's Rule: Time

Before Christ teaches us the Lord’s Prayer he explains that God is with us before we pray [Matthew 6.7 (for your Father knows what you need before you pray), Benedict repeating that in his Rule [et antequam me invocetis, dicam vobis: Ecce adsum], and Julian in her Showing [P77-77v (Beholde and se that I haue done alle thys before thy prayer. And now thou arte. and prayest me)]. Julian likewise joins this concept, with Paul in Romans 8.26, saying the Holy Spirit is beside us moaning and mourning until we turn to God [P166v-167 (and there I sey he abydyth vs monyng and mornyng . . . for we are not onyd with oure lorde)]. Julian will end by saying 'that or god made vs he lovyd vs . . . In our makyng we had begynnyng. but the loue wher in he made vs. was in hym fro without begynnyng' [P173v].

IV. Pseudo-Dionysius, Mystica Theologia, and Augustine, Confessions

Some of Julian’s concept of our Time, God’s Eternity, comes from her knowledge, through Adam Easton, of Pseudo-Dionysius, and whom she herself mentions [P37-37v (Seynte dyonisi of france. whyche was that tyme a paynym . . .)]. Among these is the comment, 'I sawe God in a poynt' [W82, P23v-25, 62v, A101v.20], present in all versions of the Showing, a perception also in Augustine, in Boethius and in Dante.

Central to Pseudo-Dionysius and to Julian in all three of her versions are the concepts of God as 'ground of our prayer' [W73, 89v, 90v (I am grounde of thi prayer & of thy besekyngis), 92, 93, 93v, 100, 101, 103, 104, P73v (I am grounde of thy besekyng, here rubricated as in the Paris Manuscript)-74, etc., A107v, 108v, 109, 109v) and of the 'touching (epafh) of the Holy Spirit' [P10 (ffor this is the kynde dwellyng of the sowle by the touchyng of the holie ghost), etc.], initially noticed by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds 'Literary Influences', Leeds Studies in English 7-8 (1952), 23-24.

The prayer to the Trinity as Wisdom in the Mystica Theologia is illuminated in Adam Easton’s thirteenth-century Victorine manuscript of Pseudo-Dionysius with a most lovely Romanesque T in gold leaf, lapis lazuli blue and leafy green intertwines. Easton was a Benedictine of Norwich's Cathedral of the Holy and Undivided Trinity's Priory. The Cloud Author translates this invocation as 'This is Seinte Deionise Preier, Thou vnbigonne & euerlastyng Wysdome. the which in thiself arte the souereyn-substancyal Firstheed, the souereyn Goddesse, & the souereyn Good, the inliche beholder of the godliche maad wisdome of Cristen men.'6 Julian, again and again, uses Trinitarian theology, often derived from Pseudo-Dionysius, such as we also find in Dante Alighieri's Commedia, of God as Might, Wisdom, Love [W83, P25, 63, 124v, 154-154v, etc., A100, 112, 114].7

Cambridge University Library Ii.III.32, fol. 108v

Julian quotes Augustine on our restlessness unless we rest in him [W74v-76, P9v-10,, A99-100, etc., at P71v-72] seeing this peace and charity as attained through prayer. She also sees Augustine's City of God, the Gospels' Kingdom of God, as tented within us, God reigning within our soul as womb [W101v, P87, 103v, 113v, 143v-146v (And then oure good lorde opynyd my gostely eye. and shewde me my soule in the myddys of my harte. I saw the soule. so large as it were an endlesse warde. and also as it were a blessyd kyngdom), A102v-103, 112, 115.4]. We know that Julian's anchorhold was near the Augustinian house on the River Wensum and she may have had access to their theological library.

Several contemporary writers resonate with Julian's writings on prayer, the Franciscan Tertiary Angela da Foligno, the Benedictine Hermit John Whiterig, the Augustinian Hermit William Flete, the Dominican Tertiary Catherine of Siena, the Cloud Author and Walter Hilton. Angela of Foligno wrote 'God is closer to us than our own soul', which Julian repeats [W101, P118.14]. They are part of an axis of contemplatives related to the Pan-European Dominicans known as the 'Friends of God' sparked by the Pseudo-Dionysian Mirror of Simple Souls written by the beguine Marguerite Porete. Adam Easton was in a position to bring the writings of Marguerite Porete, Angela of Foligno, Jan van Ruusbroec, Henry Suso, Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena to England, and to a Norwich anchorhold, and we even have the bills for the shipping of his many books, first between Norwich and Oxford, then from the Low Countries to Norwich.8 John Whiterig, Easton would have known as a fellow-Benedictine student at Oxford.9 Compare, for instance, Julian's Prayer in the Showing of Love [W75v,76],

| God for thi goodnes yeue

vnto me thy selfe: for thou art I nough to me. & I may no thyng aske that is lesse . that may be full wur shypp to thee. And yf I aske eny |

thyng that is lesse. euer me wantith. but only in the I haue all. |

with John Whiterig's Prayer in Meditacio ad Crucifixum (Chap. 5, fol. 8), on the handout:

Aliud nolo triticum nisi temetipsum: da michi ergo teipsum, et cetere tolle tibi. Quid enim michi est in celo, et quid plus quam te optaui super terram? Certe quicquid est preter te non michi sufficit preter te, nec est munus apud te quod tantum desidero sicut te. Si ergo uelis replere in bonis desiderium meum, nichil aliud michi des nisi temetipsum. Non enim coram te cupiditas mea placeret si aliquid aliud, quod tu non es, plus quam te optaret.While the Augustinian Hermit William Flete, whose Middle English Remedies Against Temptations Julian quotes again and again, became Catherine of Siena's spiritual director.10 Four of these, Birgitta of Sweden, Catherine of Siena, William Flete and Adam Easton, worked closely in support of Pope Urban VI, and their circle was intensely involved in the production of Birgitta's vast Revelationes, presented to the Heads of Church and State throughout Europe.11[I wish for no other wheat but thee: give me thyself, and the rest take for thyself. For what have I in heaven, and what have I desired more than thee on earth? Whatever there is besides thee does not satisfy me without thee, nor hast thou any gift to bestow which I desire so much as thee. If therefore thou hast a mind to satisfy my desire with good things, give me nought but thyself. For my desire would not be pleasing in thy sight, if I longed for something other than thee more than thee.]

Birgitta, likewise, was famed for the enditing of prayers; even the 'XV O's' contemplating the Crucifixion, in England, then on the Continent, used by Julian in the Long Texts, becoming ascribed to St Birgitta. Officially, the Swedish saint creates 'IV Oraciones', 'Four Prayers', and by contamination one of Julian's manuscripts so writes [A109 (Aftyr this oure lorde schewed me foure prayers)], instead of 'For prayer' [W89, P73.19].12

V. Shema, Love of God and Neighbour:

Adam Easton, the Norwich Benedictine, taught Hebrew at Oxford, then worked in the Papal Curia, first in Avignon, then in Rome, becoming Cardinal of England and being buried in his titular basilica, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere.13 In his student disputations and in his later writings he often joked on the meanings of his name 'Adam' from the Hebrew as Everyone, as Red, as Earthly Clay. Julian makes the same observations [P53-53v, 95v, 97 (for in the syghte of god alle man is oone man. and oone man is alle man), 98, 98v, 101v (When Adam felle godes sonne fell. for the ryght onyng whych was made in hevyn. goddys sonne myght nott be seperath from Adam. for by Adam I vnderstond alle man), 102, 103, 105v, 107, 108, 108v, 110v, 112v (whan god shulde make mannes body he toke the slyme of the erth, which is a mater medelyd and gaderyd of alle bodely thynges. and thereof he made mannes body, But to the makyng of mannys soule he wolde take ryght nought. but made it. And thus is the kynde made ryght=fully onyd to the maker whych is substauncyall kynde unmade that is god), P113v (And truly as I vnderstode in oure lordes menyng. where the blessyd soule of crist is, there is the substance of alle the soules that shall be savyd by crist), A100-101v, 106v]. Birgitta likewise had had in Magister Mathias an initial spiritual director with the knowledge of Hebrew who translated the Bible for her from Hebrew into Swedish. Alfonso of Jaén, Birgitta's subsequent director and editor, in his Epistola Solitaria validating her Revelaciones, cited the example of Huldah the Prophetess who had ordered that the Torah be studied when it was discovered, neglected, in a cupboard in the Temple. Adam Easton, who translated the Bible from Hebrew into Latin, effected Birgitta of Sweden's canonization in 1391. Julian of Norwich in the Showing of Love translated excerpts from the Hebrew Bible into English, long before the King James Bible Authorized Version.14

Julian uses the prayer of the Shema of loving God with heart, mind, strength and soul and one's neighbour as oneself, from both the Hebrew Scriptures (Leviticus 19.18) and the Gospels (Mark 12.29-31), to explain the 'oneing' in prayer to God [W93v (he wyll that our vndir=stondyng be grounded with all our myghtis. all our entent. & all oure meanyng), P18v (ffor in ma=nkynde that shall be savyd is compre=hendyd alle. that is to sey. alle that is made. and the maker of alle. ffor in man is god. and in god is alle. And he that lovyth thus. he lovyth alle), 67 (What may make me more to loue myn evyn cristen. than to see in god. that he louyth alle that shalle be sa=vyd. as it were alle one soule. ffor in every soule that shalle be savyd. is a godly wylle that nevyr assentyth to synne. nor nevyr shalle), 78v (Prayer onyth the soule to god), 84v (ffor our soule is so fulsomly onyd to god. of his owne goodnesse. that between god and our soule may be ryght nought), 91 (Sodenly is the soule onyd to god. when she is truly peesyd in her selfe for in hym is founde no wrath), 107v (we assent to god when we fele hym truly. wyllyng to be with hym. with all oure herte. with all oure soule. and with all oure myghte), 113-113v (And ferthermore he wyll we wytt that this deerwurthy soule was preciously knytt to hym in the makyng. whych knott is so suttel and so myghty that it is onyd in to god. In whych onyng it is made endlesly holy. ffarthermore he wyll we wytt that all the soulys that shalle be savyd in hevyn without ende be knytt in this knott and onyd in the oonyng and made holy in this holynesse) A113v (Whenn wrechidnesse is departed fra vs, god and the saule is alle ane and god and man alle ane), 115].

Thus the Shema of Julian blends into Shalom,

that totalization of peace as rest instead of restlessness,

of wholeness and wellness, far more encompassing than is

the Greek eirhnh. Julian also translates Shalom better

than does Jerome's 'recte' or than does Wyclif's

'ri3t', instead as [P50 (all

shalle be wele. And alle Shalle be wele. And alle maner of

thynge Shalle be wele), 51,

54v-55, 57-59v, 62,62v, A106, 106v, 108]. Through Adam, Julian

has access to Greek and Orthodox theology by way of

Pseudo-Dionysius, and she has access to Hebrew philology and

theology by way of his knowledge of Rabbi David Kimhi who

argued that philology and theology are one in another

manuscript Easton had owned and similarly carefully annotated,

as well as Easton's translation of the whole Hebrew Bible.15

VI. The Gospel, the Vita Christi

Julian knew Sir Miles Stapleton who was the executor of the 1416 Will of Isabella Ufford, Countess of Suffolk, in which Julian was left a legacy, three years following the 1413 Amherst Short Text Version's enditing.16 Sir Miles Stapleton had a manuscript created in 1405 by an Augustinian Hermit on the Passion of Christ.17 We recall that Julian desires to share in the Crucifixion, to be with Mary Magdalen [P45, W85v, (begynninge at the swete incarnacion. and lestyng tyl the blessed vprising on ester day in the mornyng), P3v (Me thought I woulde haue ben that tyme with maddaleyne and with other that were Christus louers that I might haue seen bodilie the pa=ssion that our lord suffered for me. that I might haue suffered with him as other did that loved him), A97]. And that all in the Middle Ages but Abelard believed Pseudo-Dionysius had witnessed the Crucifixion and so been converted, Aquinas citing Dionysius the Areopagite more than a thousand times as a revered Church Father.

Julian describes Christ's Passion as if present, as witness. She speaks of the sensuousness of our knowing of God, in Augustinian terms, in Eucharistic terms [P80v, W96v]:

And than shall we all come inSir Miles Stapleton’s Passionem Christi, compiled from the four Gospels by the Augustinian Hermit Michael de Massa, lets us smell the flower fragrance, lets us hear the blackbird’s sweet song, lets us see the flowing of the blood, has us look into Mary Magalene’s eyes. Medieval prayer was as sensual as God’s Creation. For this reason we see gold leaf on purple for the initials of the Norwich Castle Manuscript, and gold leaf again on Sir Miles Stapleton's manuscript, like that on the glory of the Pseudo-Dionysius prayer to the Trinitas. Sir Miles' daughter, Lady Emma Stapleton, became anchoress to the White Friars, the Carmelites, in Norwich and it is possible that the Amherst Manuscript, begun in 1413, and containing Richard Rolle, Julian of Norwich, and the 'Friends of God' circle of Marguerite Porete, Jan van Ruusbroec, Henry Suso, and Birgitta of Sweden, was compiled for her anachoritic reading and her contemplation, to aid her in her prayer.18 Prayer through time is a chorus of voices, a sacred conversation amongst our even-Christians, a treasury laid up here and now in Heaven's Eternity.19

to oure lord god our selfe clerely

knowyng. and god fulsomly

hauyng. and we endelesly be

had all in god. hym vereyly

seyng & fulsomly felyng. & hym

goostly felyng & hym goostly

herynge & delytably smellyng

and swetely swalowyng. and

thus shall we se god face to

face. homly and fulsomly. The

creature that is made shall se

and endelesly behold god that

is the maker.

Conclusion:

Thomas Merton20 and T.S. Eliot both praise Julian, the one as

mystic, the other as writer of English. The beauty of her

English is because it is prayer to God and for neighbour. For

us. Who have God’s Word in us, in English, as well as in

Latin, in Greek, in Hebrew. Like God’s Daughter, Wisdom, we

shape and share in the Creation. Like St Christopher and the

Theotokos, whether men or women, we become as God-bearers; and

we, too, can hold in our hands the Creation as Book, as Showing

of Love - in the quantity of a hazelnut - through

our oned prayer.

NOTES

1 Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., University of Leeds Theses: An Edition of MS Sloane 2499 of Sixteen Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich Presented as a Thesis for the Degree of Master of Arts, May 1947; Critical Edition of the Revelations of Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1416), Prepared from all the Known Manuscripts with Introduction, Notes, and Select Glossary, Presented as a Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Language and Medieval Literature, May 1956. Together we edit all the extant manuscripts in Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love (Florence: SISMEL: Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2001): Westminster Cathedral (siglum W), on loan to Westminster Abbey; Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS anglais 40 (siglum P); British Library, Sloane 2499 (siglum S1); British Library, Amherst, MS Add. 37,790 (siglum A). Siglum established in her University of Leeds, M.A. Thesis, 1947. Our edition replicates the manuscripts' folios, citations here being made to siglum, folio and, where necessary, line numbers, e.g. P141v.

Two earlier and two more recent studies of use to this paper have been André Vauchez, La Saintété en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Age: d'après les procès de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, 1981), on canonization; Jean Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture (New York: Fordham University Press, 1977), and Christopher Abbott, Julian of Norwich: Autobiography and Theology (Cambridge: Brewer, 1999), for the monastic lectio divina of Julian's text; and Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt, Julian of Norwich and the Mystical Body Politic of Christ (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), for its insights on Julian's 'oneing'.

2 Nicholas Watson raised the possibility that the Amherst Short Text was not the earliest version but, instead, later: 'The Composition of Julian of Norwich's Revelation of Love', Speculum 68 (1993), 637-683; 'Censorship and Cultural Change in Late-Medieval England: Vernacular Theology, the Oxford Translation Debate, and Arundel's Constitutions of 1409', Speculum 70 (1995), 822-864.

3 The manuscript in Norwich Castle, 158.926/4g.5, exhibits features related to those found in some of the manuscripts containing Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love and similar works. It has iii + 89 folios, measuring 190 x 130 millimetres, the text area being 142 x 90 millimetres, in 27 lines to the page. It has some illuminated capitals in gold leaf upon a purple background, as above, which interestingly replicate those St Lioba's St Boniface describes as made by English nuns in England and in Germany in the Anglo-Saxon period, likely under Abbess Hilda's influence. Its rulings are similar to those in the Westminster and Paris manuscripts, though beyond the opening pages these are uninked, merely scored. It uses rubricated paragraph signs, as in the Paris Manuscript. It is bound in its original boards, though the clasps are now lost. Neil Ker dates it as written at the beginning of the fifteenth century. It contains 'Theological Treatises', specifically 'An Epistle of St Jerome [actually Pelagius] to the Maid Demetriade who had vowed Chastity', a 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins', a 'Treatise on the Pater Noster', and the 'Pore Caitif'. Richard Copsey, O.Carm. notes that the 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins', is one written by Richard Lavenham, O.Carm., who lectured on Birgitta's Revelationes at Oxford and who was Richard II's confessor. It uses similar dialect forms as are found especially in the Sloane Manuscripts chapter headings to the Julian Showing of Love, for instance, 'arn' for 'be', and throughout employs a similar vocabulary of ideas as that employed by Julian, 'behouely', 'byddyngs and forbyddyngs', 'woo', 'travail', 'sekir'. It uses Middle English letters, ff for capital F, and thorns, yoghs and longtailed median s's. See http://www.umilta.net/norcastl.html

4 Lambeth Palace 3600 (L), with English rubrics and Latin and English contemplative prayers at folios 59v-66v. See http://www.umilta.net/lambeth.html

5 Millard Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century (New York: Harper, 1964), pp. 132-156. In particular the Simone Martini fresco of the 'Madonna in Humility' painted for and with the Cardinal Stefaneschi at Avignon would have been known to the English Cardinal, Adam Easton, O.S.B. See also Juliana Dresvina, http://www.florin.ms/beth4.html§

6 This manuscript, Cambridge University Library Ii.III.32, fol. 108v, Norwich Cathedral Priory shelfmark X.ccxxviii, is highest surviving manuscript number of the six barrels of books Easton willed to his monastery, telling us that Adam Easton owned at least 228 manuscripts. Another of Easton's manuscripts, Origen, Homelia in Leviticum, Cambridge University Library, Ii.I.21, Norwich Cathedral Priory shelfmark X.cxx, includes, 'Aut tibi videtur Paulus cum ingressus est theatrum, vel cum ingressus est Areopagum, et praedicavit Atheniensibus Christum, in sanctis fuisse? Sed et dum perambulasset aras et idola Atheniensium ubi invenit scriptum ''Ignoto Deo'''. Origen's writings for nuns are particularly sensitive to women in the Bible, discussing for instance the woman touching Christ's fringed garment. Both the Cloud Author and Julian use that episode.

The Cloud Author, whom I consider to be Adam Easton writing to Julian, takes this particular passage and translates 'Trinitas' as 'Wisdom', Deonise Hid Diuinite and other Treatises on Contemplative Prayer Related to The Cloud of Unknowing, ed. Phyllis Hodgson (Oxford, Early English Text Society, 1958), E.E.T.S. 231, p. 2.

For Adam Easton, see Leslie John MacFarlane, 'The Life and Writings of Adam Easton, O.S.B.', University of London, Doctoral Thesis, 1955, 2 vols; Eric College, A Syon Centenary (Syon Abbey, 1961), pp. 5-6; James Hogg, 'Cardinal Easton's Letter to the Abbess and Community of Vadstena, Studies in St Birgitta, ed. Hogg, II. 21; 'Adam Easton's Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae', The Medieval Mystical Tradition, Volume 6, ed. Marion Glasscoe (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer, 1999), p. 234; Eric Colledge, 'Epistola solitarii ad reges: Alphonse of Pecha as Organizer of Birgittine and Urbanist Propaganda', Mediaeval Studies 18 (1975), 19-49; De S. Birgitta vidua, Acta Sanctorum [ASS] (Paris: Victor Palme, 1867), October 8, Oct IV, vol. 50, 369A, 412A, 468A, 473C.

7 Thomas Aquinas, O.P., Summa Theologiae I.39.8.3, explained it was heresy to so divide the Trinity into separate parts. The Trinity as Might, Wisdom, Love is rare amongst the Church Fathers, though it is employed by Abelard, Bernard, John of Salisbury, Marguerite Porete, Dante Alighieri, from Pseudo-Dionysius.

8 Marguerite Porete, Mirror of Simple Souls, was published as by a male Carthusian, and with the imprimatur, in the same series of Orchard Books, as which presented Julian's Showing in the twentieth century, being then unaware that first the text and then its authoress had been burned at the stake in Paris, 1310: [Anonymous], The Mirror of Simple Souls, ed. Clare Kirchberger (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1927; Revelations of Divine Love Shewed to a Devout Ankress, by Name Julian of Norwich, ed. Dom Roger Hudleston, O.S.B. (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1927). Its Middle English version in the Amherst Manuscript and in two others is accompanied by an authorizing gloss written by one 'M.N.' Paul Verdeyen, 'Le procès d'inquisition contre Marguerite Porete et Guiard de Cressonessart, Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique 81 (1986), 47-94.

Joan Greatrex notes the bill for shipping the Benedictine student Adam Easton's manuscripts back to Oxford following a preaching mission in Norwich, 1367-1368: 'In expensis Ade de Easton versus Oxoniem et circa cariacionem librorum eiusdem, cxiijs iiid ': NRO DCN 1/12/30, Sacrist contributes to his inception, NRO DCN 1/4/35, Refectorer, NRO DCN 1/8/42, Master of Cellar, 30s, to 'master of divinity', NRO DCN 1/1/49. Then, much later, circa 1389, the bills for shipping the Cardinal's books to Norwich through Flanders, Norwich Cathedral Priory Master paying 48s 7d, the Almoner 10s 'pro cariagio librorum domini cardinalis', the Benedictine Prior of Lynn contributing 20s 'circa libros domini Ade de Eston': NRO DCN 1/1/65; 1/6/23; 2/1/17/

9 John Whiterig, 'The Meditations of the Monk of Farne', ed. Hugh Farmer, O.S.B. Studia Anselmiana 41 (1957), 141-245; Christ Crucified and Other Meditations of a Durham Hermit, ed. David Hugh Farmer, trans. Dame Frideswide Sandeman, O.S.B. (Leominster: Gracewing, 1994); P. Franklin Chambers drew attention to the similarities between the two contemplative writers in his Juliana of Norwich: An Introductory Appreciation and an Interpretative Anthology (London: Gollancz, 1955). The manuscript transcribed is Durham B.iv.34, fols. 5v-75, and is the only extant manuscript with this text. See http://www.umilta.net/whiterig.html

10 'Remedies Against Temptations : The Third English Version of William Flete,' ed. Eric Colledge and Noel Chadwick, Archivio Italiano per la Storia della Pietà 5 (Rome, 1968).

11 Carl Nordenfalk, 'Saint Bridget of Sweden as Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts'. De Artibus opuscula XL: Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky, ed. Millard Meiss (New York: New York University Press, 1961), pp. 371-393, 38 figures; James Hogg, 'Cardinal Easton's Letter to the Abbess and Community of Vadstena', Studies in St Birgitta and the Brigittine Order (Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 1993), 2:20-26; 'Adam Easton's Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae', in The Medieval Mystical Tradition, ed. Marion Glasscoe, (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1999), 6:213-240.

12 Nicholas Rogers, 'About the XV O's, the Brigittines and Syon Abbey', St Ansgar's Bulletin, 80 (1984), 29-30; Birgitta of Sweden, 'Four Prayers', Revelaciones XII: I To the Virgin, II To Christ, III To the Body of Christ, IV To the Body of the Virgin. See http://www.umilta.net/xvo's.html

13 Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Tomb of Adam Easton:

14 When Julian created her Parable of the Lord and the Servant, writing it circa 1387-93, she seemed to be drawing on the rich Coronation iconography concerning Richard II and Anne of Bohemia, the one a king, the other an emperor’s daughter, that perhaps Cardinal Adam Easton had orchestrated already in the Victorine Liber Regalis. Julian would also have been aware of her scarlet-clad Cardinal of England’s name of ‘Adam’, as meaning in Hebrew ‘red’ and ‘Everyman’, in Hebrew. Indeed, in the Westminster Liber Regalis this comment is made, that among the colours of the jewels in the royal crown, the sardis is red, the colour of red clay, of regality, yet of the earth, of the ‘son of Adam’, ‘son of Man’, Christ’s humble term for himself, Adam/Everyman made by God from red clay, p. 58, in this replicating many of Adam Easton’s texts playing upon the Hebrew meanings of his name, likewise used by the Cloud Author, and echoed as well in Julian of Norwich’s Long Text of the Showing of Love (P53).

But Julian gives neither the Lord nor the Servant scarlet garb. She vests the Lord in blue, the Servant first in sweat-stained rags, then in the hues of rainbows. Cardinal Jerome had written to the Roman noblewoman Fabiola a treatise, Epistola LXIV, explaining the High Priest Aaron’s garb in Exodus, specifically dwelling upon the hycinthine blue of his ephod: Hieronymus ad Fabiolam de vestitu sacerdotum, ‘compulisti me, fabiola, litteris tuis, ut de aaron tibi scriberem uestimentis’, Opus Epistolarum diui Hieronymi Stridonensis, una cum scholiis Des. Erasmi Roterodami, denuo per illum non vulgari rocognitum, correctum et locupletum (Parisiis: Guillard, 1546), III.18v-21v. Adam Easton wrote on the Pope as Christendom’s High Priest, as Aaron, using both Jerome and Pseudo-Dionysius, in his Defensorium Ecclesiastice Potestatis. Julian seems, for her allegory, to have been reading Jerome’s Epistle to Fabiola on the blueness of Aaron’s robe, and Zachariah’s Book of Prophecy, on the filthy rags, both of which are texts Adam Easton had studied for his Defensorium Ecclesiastice Potestatis that had won for him his Cardinalate. For Zachariah parallel, see Brant Pelphrey, Love was his Meaning: The Theology and Mysticism of Julian of Norwich (Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 1987), Christ our Mother (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1989).

Alfonso of Jaén, Epistola Solitaria: 22 non attendentes, quod Deus omnipotens tam in Veteri quam in Nouo Testamento ad ostendendum omnipotenciam suam sepe infirma mundi elegit sibi tam in femineo sexu quam in masculis, vt confundat sapientes. 23 Nonne de pastore fecit prophetam et iuuenes ydiotas repleuit spiritu prophecie? Et nonne non doctores sed piscatores et rudes homines elegit in apostolos, qui spiritu sancto repleti sunt? 24 Numquid non eciam Maria, soror Aaron, Iudith et Hester spiritu prophecie dotate fuerunt? Numquid non per Oldan mulierem prophetissam rex Iosias in agendis directus est? 25 Nonne recordaris,quod Delbora prophetissa rexit populum Israel, Anna quoque, mater Samuelis, Agar et vxor Manue, mater Sampson et alie femine in Veteri Testamento prophecie spiritum habuerunt? 26 In Nouo eciam Testamento Anna, Fanuel filia, prophetauit, Elizabeth Zacharie, beata Lucia virgo, vt habetur in libris suis, Sibilla Tyburtina, Sibilla Erictea et multe alie, de quibus in libris Sacre Scripture et sanctorum copiam magnam inuenies.

The Norwich Carmelite John Bale notes of Adam Easton: 'Iste multa opuscula edidisse per ea tempora perhibetur, ac Biblia tota ab hebreo in latinum transtulisse'

15 The Stanbrook

Abbey Hermit Maria Boulding has discussed the difference

between shalom and eirhnh, in The Coming of God

(London: Collins, 1984), pp. 200-201, citing John MacQuarrie,

The Concept of Peace (New York: Harper, 1973).

Rabbi David Kimhi, Sepher Ha-Miklol

(Book of Perfection) Sepher Ha-Shorashim (Book of

Roots), Cambridge, St John's College 218 (I.10), Norwich

Cathedral Priory shelfmark X.clxxxxij; The Longer

Commentaries of R. David Kimhi on the First Book of the

Psalms, trans. R.G. Finch, intro. G.H. Box (London:

SPCK, 1919), p. 16, noting of Deuteronomy 32.18, ' He is to

you as a father, and the one that gave thee birth - that is

the mother'. For further material, bibliography, see http://www.glaird.com/contents.htm§. Easton came

back again to Norwich on a preaching mission, in 1367-1368,

and at the same time that Julian may have been writing the

Westminster Cathedral Manuscript (W)'s original version at 25.

16 Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., citing E.F. Jacob and H.C. Johnson, The Register of Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1414-1443 (Oxford 1937), II.95.

17 I owe my knowledge of this manuscript to Juliana Dresvina, Magdalene College, Cambridge University.

18 See 'Amherst Project', http://www.umilta.net/amherst.html

19 Brian Stock, Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983) works equally well for the theological writings of the fourteenth-century 'Friends of God' movement by women and men, some of whose texts are in the Amherst Manuscript with Julian's earliest surviving Showing, British Library, Add. 37,790; for the concept of choral voice in prayer, see George Guiver, C.R. Company of Voices: Daily Prayer and the People of God (London: S.P.C.K., 1988); also in Italian (Jaca Book).

20 'Julian is without doubt one of the most

wonderful of all Christian voices. She gets greater and

greater in my eyes as I grow older, and wheras in the old days

I used to be crazy about St John of the Cross, I would not

exchange him now for Julian if you gave me the world and the

Indies and all the Spanish mystics rolled up in one bundle. I

think that Julian of Norwich is with Newman the greatest

English theologian'. Thomas Merton, in an unpublished letter,

to Mt St Bernard Abbey, July 8th 1974.

Go to Text: http://www.umilta.net/JulianPrayerText.html

A

limited edition of these two files and a CD of the

oral reading together in hand-bound books set in

William Morris type and with marbled paper covers

can be obtained from Florence's English Cemetery's Hermit.

Indices to Umiltà Website's

Essays on Julian:

Preface

Influences

on Julian

Her

Self

Her

Contemporaries

Her

Manuscript Texts ♫ with recorded readings of

them

About

Her Manuscript Texts

After

Julian, Her Editors

Julian

in our Day

Publications related to Julian:

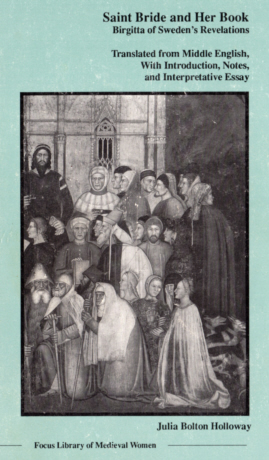

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

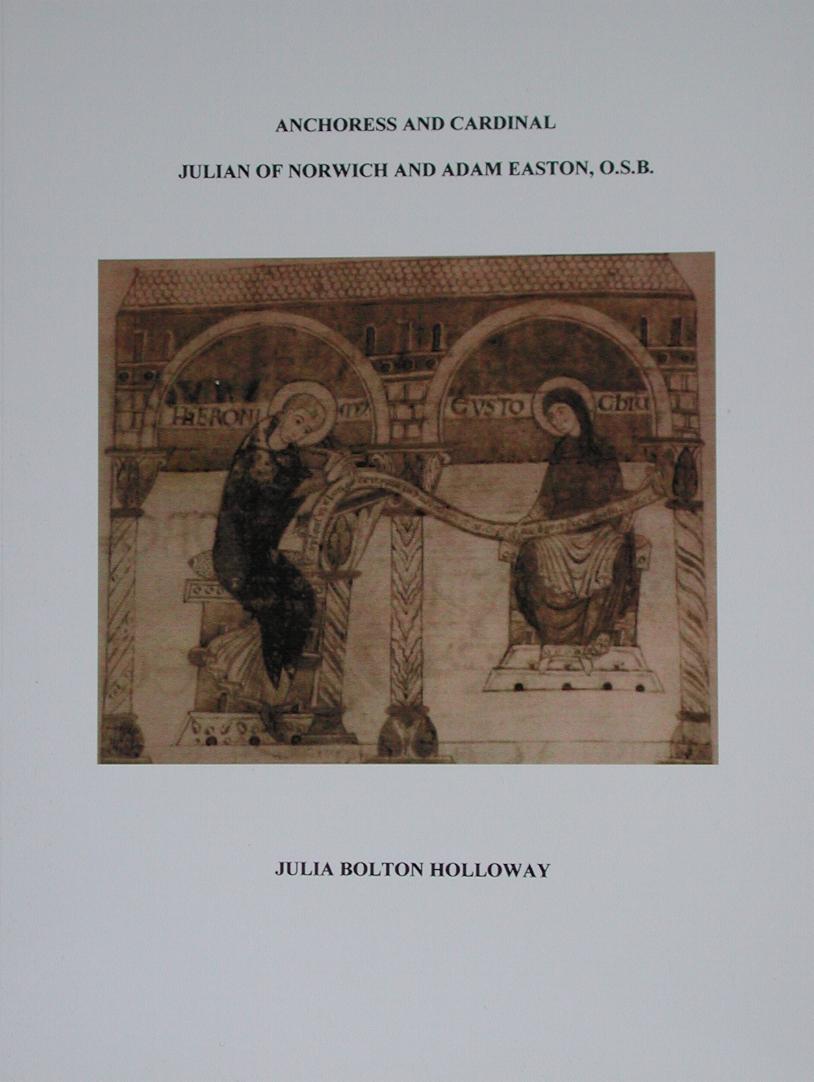

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |