JULIAN OF

NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2023 JULIA

BOLTON HOLLOWAY

| || JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY || Originally

published, Peregrina Press, 1991

Audio File of this Text, http://www.umilta.net/birgitvita.mp3

THOMAS GASCOIGNE

THE

LIFE

OF

ST

BIRGITTA

his

translation from the Middle English text, The Life of Saint Birgitta,

includes a more complete translation of her vita than I present in

the introductory pages of Saint

Bride and her Book: Birgitta of Sweden’s Revelations.1 Saint Bride and her Book

consists of an edition and translation of a manuscript of her

Revelationes —

perhaps transcribed at Syon Abbey in England — and a

discussion of her political involvement with kings and

emperors, bishops and popes.2

his

translation from the Middle English text, The Life of Saint Birgitta,

includes a more complete translation of her vita than I present in

the introductory pages of Saint

Bride and her Book: Birgitta of Sweden’s Revelations.1 Saint Bride and her Book

consists of an edition and translation of a manuscript of her

Revelationes —

perhaps transcribed at Syon Abbey in England — and a

discussion of her political involvement with kings and

emperors, bishops and popes.2

I would like to

thank Jane Chance and Ron Pullins for permission to republish

some of the material from Saint Bridget of Sweden’s

Revelations; Chancellor James N. Corbridge and the Graduate

Committee on Research and Creative Work, the University of

Colorado, Boulder, for enabling the research travel this book

required; the magnificent libraries of Sweden, England,

France, Bavaria and Italy and their holdings of Brigittine

manuscripts; the Brigittine nuns of Vadstena, Altomünster,

Syon, and the Casa di Santa Brigida, Rome; and Margot King for

her encouragement and the labour of love that is Peregrina

Publishing.

Medieval Studies Program

University of Colorado, Boulder

Ascensiontide, 1991

INTRODUCTION

decade ago André Vauchez called for

the investigation of saints' lives as an important dimension

of historical studies.3 Such historical insights can be found in the

life of Saint Birgitta of Sweden, for here we have a woman

who was marginalised because of her gender and who overcame

that marginalisation through religion. On the basis of an

acknowledged sanctity and a theocratic equality, she was

able to communicate effectively with emperors and popes,

kings and bishops, women and men, children and servants. Her

life work was the creation of an apocalyptic, sibylline book

in eight volumes, the Revelationes, and though her reputation was

to be attacked by Jean Gerson, Chancellor of the University

of Paris, it was also very ably defended by Thomas

Gascoigne, who was Chancellor of the University of Oxford.4 The first vita

of St. Birgitta was

compiled by Bishop Alfonso of Jæn and Petrus Olavi of her

household and written in Latin by Archbishop Birger

Gregersson of Uppsala and Nicholas Hermanni, bishop of

Linköping, during the process of her canonisation.5 Its Middle English version was

possibly translated by Thomas Gascoigne.6 As a young chaplain to Henry

Fitzhugh, he had gone to Vadstena in Sweden when Fitzhugh

was arranging for a royal marriage between the houses of

Sweden and England and, while there, had visited the

Brigittine mother house. Gascoigne himself says that the life he

compiled of Saint Birgitta was copied at Syon from the books

of attestation for her canonisation and written twice, on

paper and parchment.7 A comparison of three documents-the Pynson 1516

Life, a document in the Florentine State Archives from the

Paradiso monastery written by Johannes Johannis and dated

from Vadstena 1390, and another from Vadstena which was

probably written by the same scribe in 1427 and which gives

the lives of Saint Catherine and Petrus Olavi-reveals their

similarities. All three are authoritative and present

compelling narratives.

Some doubt has been cast on Thomas Gascoigne's authorship of this particular version of the life.8 It is true that it is best to consider the vita of the saint as a communal effort, shaped by many-including her confessors-and first published in an authorised version by her Archbishop in Sweden to aid in the canonisation process. The version given in this book from the Middle English was printed by Pynson in 1516 in the same manner as were many other books that had initially been manuscripts at Syon but which the Brothers wanted to have available to the Sisters and the laity. Side by side with this printed and published version are Thomas Gascoigne's scrawled notes in a most undtidy hand in the margins of manuscripts connected with Birgitta and Syon. One of these—Oxford, Bodleian Library Digby 172B—gives the lives of Saint Catherine of Sweden, Birgitta's daughter and abbess of Vadstena (“Vita venerabilis domine Katerine filie beate Birgitte de regno Swecie prime Abbatisse in Monasterio Wastenii eodem Regno sito”) and Petrus Olavi, Birgitta's confessor (“Incipit vita domini Petri Olavi confessoris beate Byrgitte”). These vitae were likely written by Johannes Johannis Kalmarnensis at Vadstena in 1427 and sent to Syon. It was this manuscript which Thomas Gascoigne, a great admirer of Birgitta and collector of Brigittine relics and manuscripts, heavily annotated and extracted from it information about the saint, as well as about her family and her tutor, Master Mathias. One story in the Life of Saint Catherine recurs in this Middle English version of the Life of Saint Birgitta and is particularly endearing. Catherine is seen in the company of some noble Roman ladies, walking amidst vines and picking them . The ladies express surprise at her beautiful purple and jacinth sleeves since, in her poverty, she usually had to wear shabby clothes. In the margin of the manuscript the scribe referred to this scene: instead of the usual hand pointing at the text, he has drawn two delicate hands clothed in elegant sleeves which are reaching up to and picking a bunch of grapes.9 Thomas Gascoigne clearly remembered this episode and included it in the version which he said he had written.10 It appears again in this version printed by Pynson.

A saint's life is more than an historical account of a person's life. It is also a legend which, in Latin, means a text to be read: legere. Although intended to be true, saints' lives tend also to become fiction in order to become readable. With the best intentions, Saint Birgitta and her circle lived, shaped and told a compelling story. Italians called her “principessa”—princess—a half-truth which she did not contradict. Yet when she lived in Italy, she was often in poverty and took to begging outside the Poor Clares church of Saint Lawrence in Panisperna wearing a patched mantle made up from an old dress and thus became the drama of the princess turned beggar maid. Her patched mantle still exists11 as does the board on which she wrote her Revelationes, on which she ate her meals and on which, Thomas Gascoigne says, she died.12 At Altomünster the prioress can show pilgrims Saint Birgitta's pilgrim staff of juniper wood and her bowl made of maple wood.13 In Sweden one can see fragments of her own writing in Swedish written down upon Italian water-marked paper, the pieces sewn together in the same manner as her mantle.14 Her bones are also revered as relics: an arm bone was given to the nuns of Saint Lawrence in Panisperna and others at Altomünster and in her shrine at Vadstena.15 Thomas Gascoigne acquired another and gave it to Oxford's Oseney Abbey.16 As if in reference to this use of Saint Birgitta's relics, an exquisite illumination shows her at prayer, her arms floating from her body to the heavens.17

In following the life which

was written after her death as an obituary to obtain her

canonisation, some facets of her story are glossed over

while others are emphasised. This is true whether it be the

original version by Archbishop Birger Gregersson of Uppsala

or the one which was probably written by Chancellor Thomas

Gascoigne of Oxford and which is here presented in a

translation into Modern English from its Middle English

text.18

Her authorised, official vita,

however, presents the extraordinary

story of a very real flesh and blood woman who first appears

as virgin, then as bride, then as mother of eight children,

then as widow and, last, as saint. It presents the story of

a woman who had power, who behaved humbly and who succeeded

in all spheres which were both open and closed to women. It

presents the story of a woman who was a writer and a

pilgrim. Saint Birgitta travelled in Sweden, Norway,

Germany, Poland, France, Spain, Italy, Sicily, Cyprus, and

Jerusalem. As a result of her labours as writer and as

pilgrim, the Order of the Holy Saviour and Saint Birgitta

was approved and spread to Estonia, Finland, Denmark,

England, Mexico, as well as in all the countries she

visited. This Order still lives out the original spirit of

her Rule. The mother house now has returned to Vadstena in

Sweden in the place where she had originally founded it.

There are daughter houses today at Altomunster outside

Munich, two in Holland-Maria-Hart, Wert. and Maria-Refugie,

Uden-and one in England, having returned from exile from

Lisbon, Portugal: Syon Abbey, which is now in located in

Totnes, Devon. Other, less enclosed, versions of the Order

have recently spread world-wide. Her nuns who wear Saint

Birgitta's design of headdresses — a white crown with five red

circles of cloth upon a black veil — continue the opus

dei as she had

commanded.

Notes to Introduction

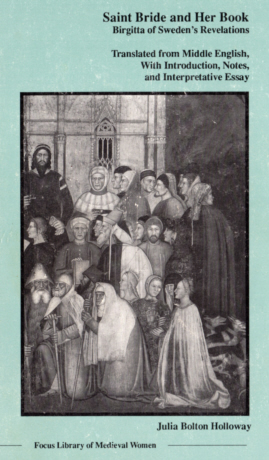

1Published by Focus Books in their series on mediæval women, edited by Professor Jane Chance, republished by Boydell and Brewer.

2Further projects are being undertaken. An essay on St. Birgitta's influence on Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe and Chaucer's Alice of Bath, with an appended list of Brigittine, Julian and Margery manuscripts and incunabula appeared in a volume on Margery Kempe, edited by Professor Sandra McEntire for Garland Press. A group of scholars edited a document in the Florentine State Archives from the Paradiso convent on Saint Birgitta's life, prepared for her canonisation in 1390, the process of which was completed in 1391. In October 1991 we presented this edited text to the Brigittine Sixth Centenary in Rome held under the auspices of the King of Sweden for the Lutherans and Lech Walesa for the Catholics—the Solidarity Movement began at the Church of Saint Birgitta, Gdansk, Poland. The magnificent editio princeps of Saint Birgitta's Revelationes was printed in Lübeck in 1492 by the Vadstena monks who had the original manuscripts at hand and it should be republished in facsimile.

3André Vauchez, La Sainteté en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Age: d'aprés les procès de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome (Palais Farnese), 1981).

4Jean Gerson, Tractatu de Probatione Spiritum in Oeuvres Complètes, vol. 9 (Paris: Desclée, 1973): 179. The Cardinal Torquemada of the Inquisition was another of St. Birgitta's champions.

5See Birger Gregersson, Vita S. Birgittae in Scriptores rerum svecicarum medii aevi. 3 (Uppsala: Edvardus Berling, 1876); Birgerus Gregorii Legenda S. Birgitte, ed. Isak Collijn (Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells, 1946); Birger Gregersson, Officium Sancte Birgitte, ed. Carl-Gustaf Undhagen (Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells, 1960); AASS 50, Oct. 4): 370, 373.

6Published in The Myroure of Oure Ladye, ed. John Henry Blunt, EETS 19 (London: Early English Text Society, 1873): pp. xlvii-lix, ix, originally printed by Richard Pynson, 1516. Thomas Gascoigne also fostered the cult of Archbishop Richard le Scrope who was beheaded Whitmonday, June 8, 1405 by King Henry IV, after giving a speech on the five wounds, typical of Brigittine iconography. See Oxford, Bodleian Library, manuscript Lat. lit. f. 2= Arch f.F.11 and Ashmole Roll 26. Henry V then founded England's Brigittin Syon Abbey in 1415 to expiate the murders by his father of Richard II and Richard de Scrope. Oxford, Balliol, 225, is S. Birgittae Revelationes with Thomas Gascoigne's marginalia.

7Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 172B, fol. 27, marginal notation. R.L. Poole notes that Gascoigne translated the Life of Saint Birgitta into English “for the edification of the sisters of Sion” (Dictionary of National Biography, p. 140). He believed that this was Pynson's 1516 Life.

8Winifred A. Pronger says that the ascription is erroneous because the printed version does not contain the story of “Robert Tenant who was freed from devils by the intervention of St. Bridget... "[He] says he included this incident in the vernacular life of St. Bridget which he compiled for the nuns and monks of Syon. The vernacular life which has been printed, however, does not contain the story and so presumably was not Gascoigne's work” (“Thomas Gascoigne” English Historical Review 53 (1938): 624 and 54 (1939): 26).

9Folio 36v.

10Gascoigne says several times in marginal annotations that he wrote a life which was at Syon in England (“Syon in Anglia”). We know, in fact, that the “Annotata quadam de S. Brigitta et miraculis eius” were in the now burnt British Library Cotton Otho A. xiv, at folio 6 of the works of Ivo of Chartres. Today if one requests this manuscript, one receives a box with a few charred fragments of the writings of Hugo of Fleury. Mary Bateson noted that Gascoigne's translation of the life of Bridget which he wrote for the nuns was not in the men's catalogue. This would mean that it would have been in the uncatalogued Sisters' library (Catalogue of the Library of Syon Monastery, Isleworth [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898]: p. xiv).

11Aron Andersson and Anne Marie Franzén, Birgittareliker (Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1975): pp. 18-29, 57. The wrought button or clasp is worked in the same fashion as those seen on Brigittine manuscripts. When the Poor Clares abandoned Saint Lawrence in Panisperna, this relic was taken by them to Saint Lucy in Selci, Rome.

12Andersson and Franzén, Birgittareliker, pp. 33-44, 58-59. Thomas Gascoigne, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Digby 172, fol. 37, describes her death on a miserable board of poverty, covered by her ancient and mended mantle, “coperta de super antiquo et emendatio mantello.”

13Andersson, Birgittareliker, pp. 45-51, 59-60.

14Stockholm, Kungl. Biblioteket, manuscript A65.

15I have seen the arm reliquary in the chapter room at Altomünster. See A. Bygdén, N.-J. Gejvall and C.-H. Hjortsö, Les reliques de sainte Brigitte de Suède: examen medico-anthropologique et historique (Lund: C.W.K.Gleerup, 1954). Bones removed from Saint Birgitta's skeleton in her shrine were replaced with those from other saints.

16London, British Library, manuscript Add. 22,285, Martilogy of Syon, has paste-down written by Thomas Gascoigne (1454) “Pater dominus Robertus Bell Secundus Confessor generalis in Monasterio Syon in Anglia dedit michi Doctori Sacre Theologie Thome Gascoigne magna partem illius ossis sancte Birgitte sponse christi eterne includi in berillo inclusa incapsa seu scrinio argentes et deaurato. et sic inclusum dedi monasterio beatissime semper virginis marie de Osneye, iuxta Universitatem Oxon ...”

17Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, manuscript D255, Les Heures de Jean le Maigre dit Boucicault, fol. 42. See Carl Nordenfalk, “Saint Bridget of Sweden as Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts,” in De artibus opuscula XL: Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky, ed. Millard Meiss (New York: New York University Press, 1961): pp. 371-393 and 38 figures.

18Life of seynt Birgette, fol.c.xx in Here begynneth the kalendre of the newe Legende of England. Richard Pynson, 1516. British Library copy owned by monk of Syon. Prologue, fol. iii, “¶Moreover next after the sayde kalendre foloweth the lyfe of seynt Byrget shortlye abrygged a holy and blessed wydowe/ which lyfe is right expedyent for every maner of persone to loke upon moost in especiall for them that lyve in matrymony or in the estate of wydowhood...” Prefaced with engraving of Saint Birgitta, used also in Richard Whytforde, The Martiloge in Englisshe after the use of the chirche of Salisbury/ & as it is rede in Syon / with addicyons, printed, Wynken de Worde, 1526, and The Myrroure of Oure Lady, printed “by me Richarde Fawkes,” November 4, 1530.

Audio

File of this Text, http://www.umilta.net/birgitvita.mp3

HERE BEGINS THE LIFE OF SAINT BIRGITTA

aint

Birgitta was of the stock and lineage of the noble Gothic

kings of the kingdom of Sweden. Her father's name was

Birger and her mother's name was Sighrid.1 Once when

her grandmother was walking with her servants by the

monastery of Sko, one of the nuns of that monastery who saw

her beauty and style of dress, despised her because of the

great pride she presumed her to have. And the next night

there appeared to that nun a person of marvelous beauty who,

with an angry countenance, said to her, “Why do you backbite

my handmaid and judge her to be proud? That is not true. I

shall make a daughter come of her progeny with whom I shall

do great deeds in the world and I shall give her such great

grace that all people will marvel.”2

Later, when Saint Birgitta was in her mother's womb, it happened for various reasons that when her mother took a sea voyage, her ship was wrecked in a sudden tempest with many people in it and she was brought safely to shore. And the next night a person appeared to her in shining garments and said, “You are saved because of the child which you have in your body. Therefore nourish it with God's charity, because it is given to you by God's special goodness.”3

And when that blessed child had just been born, while a priest who was curate of a church nearby and later Bishop of Äbo4 — a man of good and virtuous life — was at prayer, he saw a bright shining cloud and in the cloud a virgin holding a book in her hand. And a voice said to him, “Birger has a daughter born to him whose marvelous voice shall be heard throughout the whole world. It will be 'a voice of gladness and health in the tabernacles of just men' (Ps. 118:15).”5

For three years after the birth of this blessed child, it was as though she had no tongue and that she would never speak. But suddenly—against the usual development of children and not stuttering in the way of other children who are beginning to speak—she said complete and full words of such things as she heard and saw.6

In her childhood she was never idle and was always doing some good works. When she was seven years old, she saw an altar near her bed and on the altar she saw our Lady sitting in bright clothing holding in her hand a precious crown and she said to her, “Birgitta, will you have this crown?” And with a mild countenance, she assented to our Lady and put it on her head. As soon as she had done this, she felt as though a circle of a crown had been tightly tied about her head and then the vision disappeared, but she never afterwards could forget this vision.7

When

she

was ten years old, she heard about our Lord's passion in a

sermon and that same night our Lord appeared to her just as

if he had been at that hour recently crucified and he said

to her, “See, Birgitta, how I am wounded.” And thinking it

had just happened, she said, “O Lord, who has done this to

you?” And our Lord answered and said, “Those who have

contempt for me and forget my charity are doing this to me.”

And from that day on she had such affection for the passion

of the Lord that she seldom restrained her weeping when she

remembered it and she “served our Lord,” as the apostle

teaches, “with humility and tears” (Act. 20:19).

And when she was about twelve years old, one night her aunt went to the bed of the holy virgin Saint Birgitta and found her kneeling all naked beside her bed. And since she believed that the virgin was being naughty, she commanded that a rod be brought to her, but as soon as she laid it on the back of the virgin to beat her with it, the rod broke into small pieces. Whereupon her aunt marvelled greatly and said to her, “Birgitta, what have you done? Has some woman not taught you some false prayers?” But weeping as she answered, she said, “No, lady. I only got out of my bed to sing and praise him who always helps me.” And the lady said to her, “Who is that?” The virgin said, “Our crucified Lord whom I recently saw.” And from that day on her foster mother honoured her and loved her more fervently than before.8

Once while Saint Birgitta was playing with maidens of her own age, the devil appeared to her with a hundred hands and feet and most foul and loathsome in appearance. When she saw this, she was terribly afraid and went straight away and placed herself before the Crucifix, but the devil soon appeared there and said, “I have no power to do anything to you unless the Crucifix allows me to do it.” And then he vanished away.9 And so our Lord delivered her from that danger.

Although she intended most fervently to live all her life as a virgin, yet both by God's providence and the counsel of her father, she was married when she was twelve years old to a noble young knight called Ulf, prince of Nericia—otherwise called Ulf Gudmarson—who was eighteen years old and also a virgin.10 For two years after their marriage they lived together virginally, but afterwards they made devout prayers to almighty God that he would keep them without sin in the act of matrimony and that it would please him to send them issue. To his pleasure they had eight children, that is to say, four sons and four daughters.11 The names of the sons were Charles, Birger, Benedict and Gudmar, and the names of the four daughters were Martha, Catherine, Ingeborg and Cecilia.

Charles, the eldest son of Saint Birgitta, was a noble

knight who was ready to risk his life to recover the Holy

Land and he went with his mother on pilgrimage towards

Jerusalem. He died on March 12th while they were at Naples

in the middle of the journey and it was shown to Saint

Birgitta in a revelation (written in the seventh Book of her

Revelations, in the thirteenth and fourteenth chapters) that on the following day of

the Ascension of our Lord, his soul went to heaven.12

And this noble knight had a son, also called Charles, who, after having attained a great understanding of Divinity, left off studying and his vocation and took a wife. After Saint Birgitta died, it happened that while he was praying at her tomb, she appeared to him holding in her hand what looked like an hourglass and she said, “Charles, do you see how this glass has almost run its course?” And he said, “Yes, lady, I see it well.” And then she said, “The end of your life is so close that there is no more left except what you see. But if you had been obedient to God, you would have lived longer than any of my other descendants and you would have been Bishop of Linköping and a pillar of the church of God.” Then he begged her to pray for him and said that he would gladly make amends in every way possible. She said, “No son, no Judgment is given and the time is past.” Soon he became ill and, taking all the sacraments of the church, he died and is buried in the Monastery of Vadstena which, while she was alive, Saint Birgitta had founded and endowed it sufficiently to support sixty nuns and twenty-five monks.

Birger, the second son of Saint Birgitta, went with his mother to Jerusalem and there he was made a knight and came with her again to Rome. And when Saint Birgitta was dead, he and his sister Catherine conveyed the relics and the bones of Saint Birgitta, their mother, to the Monastery of Vadstena in Sweden. And after great labour and expenses which Birger carried out at God's command for the Monastery of Vadstena and for his mother, he changed his life and, as is correct to believe, attained God's blessing with his saints in heaven because “the descendants of the righteous shall be blessed” (Ps. 111:2).

Benedict,

the

third son of Saint Birgitta, was ill for a long time in the

monastery of Alvastra and Saint Birgitta wept greatly on

account of it and prayed devoutly for him because she

thought it had been caused by the sins of his father and

mother. Then the devil appeared to her and said, “Woman,

what do you mean by your great weeping which thus dims your

eyesight? All your labour is in vain. Why do you believe

your tears can reach heaven?” And then our Lord was present

and he said, “The sickness of this child has not been caused

by the influence of the stars nor by his sins nor by the

sins of his father and mother but rather by the condition of

his nature and because of this, it will gain him greater

reward in heaven. Hitherto he was called Benedict, but

henceforth he shall be called the son of weeping and of

prayers and I shall shortly make an end of his need.13

Five days later there was heard, as it were, the most sweet

singing of birds between the bed upon which the child lay

and the wall. And then the soul of the child left the body.

Although Catherine, the second daughter of Saint Birgitta, was married, she lived with her husband in complete virginity. After the death of her husband, she stayed always with her mother Saint Birgitta and lived in the state of widowhood all her life. Because this blessed virgin Catherine was fervent in devotion, excellent in gravity of demeanour, fair in body and lived a blessed life so that she would give others an example of good living, the most noble women of Rome loved to be in her company. Once the most worthy matrons of the city of Rome requested that she walk with them for recreation without the walls of the city. As they walked here and there among many clusters of grapes, they wanted the blessed virgin Catherine to gather some grapes for them because she was of an elegant stature. As she stretched up her arms to the grapes, it seemed as though her arms were clothed with shining cloth of gold although, because of the voluntary poverty she had chosen, her sleeves were torn and patched. And, knowing that what they saw was a mystery and miracle of God,14 all the matrons marveled that so meek a creature and so devout a person should seem to be wearing such precious apparel when she did not.

Once the water of the Tiber river rose with such great force that it flowed over the Lateran bridge and the monastery of St. James and the many buildings which surrounded it. The citizens of Rome therefore feared for the destruction of the city and went to the house of the blessed virgin Catherine to ask her if she would go with them to the river to pray to our Lord for the city. Out of humility, however, she believed that she was unworthy to do this and wanted to be excused but when the citizens saw that their prayers were of no avail, they violently but reverently led her out of the house to the waterside. And then a marvelous thing occurred and the old miracle was revived, as in the time of Joshua when the water of the river Jordan was stopped against its natural course (cf. Jos. 3:15-16). So was it when the virgin Catherine entered into the water of the Tiber. Such virtue issued from her that by the power of almighty God, it restrained the strength of the water and compelled the stream to return to its old course very swiftly. All men rejoiced because of this and praised the great power our Lord which had been shown through his blessed virgin Saint Catherine.15

Ingeborg, the third daughter of Saint Birgitta, became a nun in the Monastery of Risaberga when she was young and there she soon yielded her soul to almighty God. When her mother knew that she was dead, she said with great joy, “O Lord Jesus Christ, blessed are you that you called her to yourself before the world had surrounded her with sin.” And soon after that Saint Birgitta fell into such great weeping and sobbing in her oratory that all who were near to her heard and said, “See how she weeps for the death of her daughter.” Then our Lord appeared to her and said, “Woman, why are you weeping? Although I know all things, yet in your words wish to know.” And she said to him, “O Lord, I weep not because my daughter is dead—in fact I am glad of that, for had she lived longer, she should have had before you a greater accounting. Rather, I weep because I had not informed her after your commandments and because I had given her examples of pride and I negligently corrected her when she did wrong.” Our Lord answered her and said, “Every mother who weeps because her daughter has offended God and has informed her after her best conscience is truly a mother of charity and a mother of tears and her daughter is the daughter of God because of the mother. But the mother who delights because her daughter behaves after the way of the world, who does not care about her manner of living but only that she be exalted and honoured in the world, is no true mother; she is rather a stepmother. Therefore for your charity and good will, your daughter will go to the kingdom of heaven by the nearest way.” Many great miracles are done at the sepulchre of the glorious virgin, Ingeborg.16

Cecilia, the fourth daughter of Saint Birgitta, was the last child she ever had and she is to be held in especially great honour because of the singular grace given to her by our blessed Lady before she was born. When, at her birth, her mother was in great peril and in despair of her life, our blessed Lady was seen to go to her in white silken clothing As she stood before the bed, she touched Saint Birgitta in divers parts of the body and all the women present there greatly marveled at it because they did not know at all who it was. As soon as our Lady had gone out of the house, Saint Birgitta was delivered without difficulty. Shortly afterwards, our Lady said to Saint Birgitta, “When you were in danger at your delivery, I came to you and helped you. and for that reason you would be unkind if you did not love me. Therefore labour so that your children shall also be my children.”

After this Saint Birgitta induced her husband to live in chastity for many years.17 In like manner, they both went with great devotion to Saint James in Galicia and then returned to their own country of Sweden18 and by common consent they both entered into religion. Ulf her husband died in that resolve on the twelfth of February, the year of our Lord, 1344, and is buried in the monastery of Alvastra.19

After her husband's death, Saint Birgitta turned all her will to God's will and proposed to forsake all worldly pleasure for the love of God. With the assistance and grace of our Lord, she decided to live in chaste widowhood all her life and she continually made her prayer to almighty God that she know by what way she might best please him. Subsequently she gave all her lands and goods to her children and to poor men so that she might follow our Lord in poverty. She reserved for herself only what which would simply and humbly serve her for meat, and drink so that thereby she might live in a simple condition. Afterwards in the year of our Lord 1346 when she was forty two years old, by the commandment of almighty God and following the example of Abraham,20 she left her own country and her carnal friends and went on pilgrimage to Rome to live there in penance and to visit the monuments of Saints Peter and Paul and the relics of other saints until she received another commandment from our Lord.

She always had with her two elderly spiritual fathers. One was a monk called Peter, Prior of Alvastra of the Cistercian Order, a virgin and a man of great intelligence and virtuous life. The other was a Swedish priest who was also a virgin and a man of holy life and who, by the commandment of almighty God, taught her and her daughter Catherine Latin grammar. All her life she obeyed her spiritual fathers in all virtue as meekly as a very humble monk is accustomed to obey his prelate and she arrived at such perfect humility, obedience and mortification of her own will that when she went to pardons and holy places along with the common people, she was always accompanied by the priest—her spiritual father—and did not dare to lift up her eyes from the ground until she had leave of the aforesaid spiritual father.21

After the death of her husband, in honour of the Trinity she wore a tightly knotted cord made of hemp next to her bare skin , as well as around each leg beneath the knee. Even when she was ill the only linen cloth she used was that which she put upon her head. Next to her skin she always wore a rough and prickly woolen cloth and her outward garments were not those of a person of her estate but were second-hand and very humble. She not only kept the fasts and vigils that holy church required, but she also added so many others to them that she went beyond the church's commandment and fasted four times each week, something which she had also done while her husband was alive as well as after he had died. After her husband's death and until a little time before her blessed passage out of this world, she habitually refreshed herself with a very short sleep after fasts, prayers and other divine labours by lying on a carpet without a featherbed, mattress, straw or any other thing and wearing her usual clothes. Every Friday she abstained and took only bread and water in remembrance of the glorious passion of our saviour Christ Jesus and she likewise practised that abstinence on many other days in honour of divers other saints. But whether she fasted or took food, she always left the table with the greatest temperance and was never not fully satiated.22 Furthermore, on Fridays she would take wax candles and let the burning drops fall upon her bare flesh so that the burned marks left a scar, and she would put gentian—a most bitter herb—into her mouth and leave it there.23

When she was in Rome, she neither feared the harsh cold nor the oppressive heat, neither rain nor the foulness of the way nor even the sharpness of the snow or hail. Even though she might have ridden, nevertheless every day she went to the Stations ordained by the church with the strength of her own lean body and she also visited many other saints' shrines. She used to kneel so much and so long that her knees became as hard as those of a camel.24

She was of such great and marvelous meekness that often she sat unknown with poor pilgrims at the Clarissan monastery of Saint Lawrence in Panisperna in the city of Rome and there would take alms with them. Often, for the sake of God, she repaired the clothes of poor men with her own hands and, while her husband lived, every day she fed twelve poor men in her house, serving and ministering to them herself in whatever their need. From her own substance she repaired many ruined hospitals in her own country and, like a busy, merciful and compassionate administrator, she visited the needy sick men who were there and she handled and washed their sores without horror or loathing.25

Her patience was so marvelous that she endured most submissively and without complaints or grumbles the illnesses she herself had suffered, the wrongs done to her, the deaths of her husband and of her son Charles, and all her other adversities. Rather she blessed our Lord in all things with great meekness and because of such troubles, she was the more constant in her faith, the more quick to hope and the more burning in charity and she greatly loved justice and impartiality. She despised and overcame the promptings of the flesh and of vainglory with constant care and great trust in our Lord. She was of such great wisdom and discretion that from her childhood to her last hour—as far as frailty might tolerate—she never said that good was evil nor evil good. During her husband's life, she made her confession every Friday and after his death she made it every day. Every Sunday she and her daughter Catherine—who lived with her all her life in penance and chaste widowhood with great devotion and humility—received the holy Body of our Lord and they lived always in secret penance. They did not show this life openly to the world but they lived it secretly before almighty God in simpleness of heart and cleanness of spirit.

Once, when the king of Sweden wanted to lay a heavy tax on his Commons so that he might repay a large loan, Saint Birgitta said to the king out of the great compassion that she had for the people, “O sire, do not do so! Rather, take my two sons and keep them as a pledge to your creditors until you are able to repay the money. Do not offend God and your subjects.”

There was a knight who was always trying to cheat the people and, by his words and evil examples, brought many to damnation. This knight was very envious of Saint Birgitta and because he himself did not dare speak evilly to her, he stirred up another man to pretend to be drunk who then said shameful and slanderous words to her so that she would lose her temper. As Saint Birgitta was sitting at the table with many worthy people, this accursed man said in the hearing of everyone present, “O lady, you sleep too little and stay awake too long. It would be expedient were you to drink well and sleep more. Do you think that God has forsaken religious people and spoken with the proud people of the world? It is a vain thing to put any faith in your words.” And as he was speaking in this way, those who were standing close to him would have violently dragged him away to his rebuke and shame, but Saint Birgitta forbade them and said, “Let him speak. Almighty God has sent him here because all my life I have sought praise. Why should I not also hear criticism? This man speaks the truth to me.” When the knight heard of Saint Birgitta's great patience, he greatly repented and came to Rome and asked her forgiveness and there he made a good and praiseworthy end.

The blessed woman, Saint Birgitta, was so adorned and filled with all virtues that our Lord received her as his spouse and visited her many times with marvelous consolations and divine grace and showed her many heavenly revelations. He said to her, “I have chosen you to be my spouse that I may show you my secrets, because it pleases me to do so” and another time he said, “I have taken you as my spouse and for my own delight such as it pleases me to have with a chaste soul.26

In

these revelations are contained the high secret mysteries of

the most glorious Trinity, of the Incarnation, the nativity,

the life and passion of our saviour Christ Jesus, as well as

the plain and true doctrine to know virtue and follow it and

to avoid vices, thereby showing the rewards of virtue and

the great intolerable pain and damnation that shall fall to

sinners who die in deadly sin. The revelations also exhort

all men to do suitable penance for the sins they have

confessed so that they may avoid the great and dreadful

pains of purgatory ordained for their cleansing through the

powerful equity of justice. Our Saviour showed these

terrible pains on different occasions to his spouse Saint

Birgitta so that she might show them to the people. Saint

Birgitta wrote these revelations in her own tongue and the

Prior of Alvastra, her spiritual father, translated them

into Latin by the commandment of almighty God and divided

them into eight books. He also translated a special

revelation that she had received concerning the praise and

excellence of our blessed Lady which he appointed to be read

for the Office of the Sisters, as well as many other

revelations concerning the Rule and foundation of her

Monastery of Vadstena, not to mention four goodly chapters

to be read as prayers along with certain Revelations

called the Extravagantes.

Despite the great and singular graces that she had through the Revelations, she was in no way proud because of them, but daily she humbled herself the more with many tears. She would gladly have hidden and kept secret the special gift that she had of our Lord in the Revelations except that our Lord frequently commanded her to write and to speak them boldly to the Pope, to the Emperor, to kings, princes and other people, so that through them they might the more quickly be converted from their sins. And when she was in prayer and contemplation, she was often seen by many devout persons to be elevated and lifted up from the ground about the height of a man.

Once an angel appeared to Saint Birgitta and, among many other things that he showed her concerning the excellence of our blessed Lady, he said that she was the mistress of the apostles, the comforter of martyrs, the teacher of confessors, the clear shining glass of virgins, the helper of widows, the giver of wholesome admonitions to those who lived in matrimony, and a great strength to those who lived in the faith of the holy church. First he said that our blessed Lady showed and declared to the apostles many things about her Son that they had not known before. He then said that she encouraged martyrs to suffer tribulation gladly in the name of Christ who had, for their sake, suffered great tribulation for many years and he added that for thirty-three years before the death of her Son, she herself had continually suffered heart ache with great patience.

Our Lady taught Saint Birgitta's confessors the very true lessons of salvation and, by her doctrine and example, they perfectly learned to order wisely the times of the day and of the night to the praise and glory of almighty God and to use good discretion with regard to their bodies in sleeping, eating and working. And virgins learned from her most virtuous life how to rule themselves honestly and how to preserve their virginal cleanliness strongly to the death, how to flee from loquacity and all vanities, how to discuss with a diligent premeditation all the works that they had to do and how to examine them carefully with in a spiritual balance. For the comfort of widows she said that, although by maternal love it had much pleased her that her Son no more wanted to die in his manhood than in his Godhead, yet she wholly conformed her will to the will of God and chose to fulfil God's will humbly and to endure all tribulation rather than to do anything against God's will for her pleasure. Speaking in this way, she thus urged widows to be patient in their tribulations and constant in all bodily temptations. She also counseled those who lived in matrimony to live together in perfect unfeigned charity in both body and soul and to keep one whole will to the honour of almighty God. She told them about herself and how she had clearly given all her faith and whole intent to almighty God and that, for his love, she never withstood his will in anything.

One day Ulf, who was her husband, appeared to Saint Birgitta after his death, and said, “For a time I felt the great justice of our Lord in Purgatory. But now mercy begins to draw nearer to me. And you shall know that in my life I sinned in five ways of which, when I was sick, I did not repent sufficiently. The first is that I took too much delight and pleasure in the wantonness of the child you know about. The second is that before my death I neglected to restore to a widow certain goods I had bought from her. To prove what I say is true, tomorrow she will come to you and do you then give her whatever she asks for, for she will only ask for what is right. The third is that I heedlessly promised a man to take his part in all his difficulties and consequently he became so bold that he attempted many things against the king and the law. The fourth is that I occupied myself in tourneys and in worldly vanities and worried more about my standing in the sight of the world than with my standing as a prophet. The fifth is that when I exiled a certain man, I was too harsh with him. Although he deserved the judgement, yet I was less merciful to him than I should have been.”

Then Saint Birgitta said to him, “O blessed soul, what has helped towards your salvation? What can help you now towards your deliverance?” And he answered, “Six things have helped me. The first is the confession I made every Friday when I still had the time and the intention to amend my sins. The second is that when I sat in judgement, I judged not for the love of money nor for favour, but I diligently examined all my judgements and was ready to correct them when I had done something I ought not to have done. The third is that I obeyed my spiritual father when he counseled me not to perform the act of matrimony after I knew a child was conceived. The fourth is that when I was lodged in any place, I was as careful as possible that neither I nor my servants were unkind to poor men. I was not untrustworthy to them and though I went into debt, I paid the wages due them. The fifth is the abstinence I observed while on pilgrimage to Saint James. I did not drink between meals and because of that abstinence, I am pardoned for having sat long at table and for my loquacity and excess. And now I am sure of salvation though I do not know the hour. The sixth is that I assigned my chattels to those whom I considered righteous and who would fulfil my obligations. Because I feared being in debt while I was alive, I surrendered the king's provinces to him so that my soul would not suffer God's judgement. Therefore now — as much as it is granted to me by almighty God — I shall ask your help and request that for a whole year you have Masses sung for me continually and for all those for whom our Lord wishes to be prayed: that is, the Masses of our Lady of the Angels and of all saints, as well as of the passion of our Lord Christ Jesus, for I trust that I shall soon be saved. Be especially diligent towards poor men and give them such vessels, horses and those other things in which in my life I took too much delight. And also if you can, do not forget to give some chalices for God's sacrifice, because truly they profit greatly to the salvation of the soul.27 Leave your properties to our children, for I never sinfully purchased anything, nor indeed would I have done so if I could.”

This blessed woman, Saint Birgitta, lived for twenty-two28 years after she left her own country. During all this time she never went to any place except by the special commandment of our Lord. It was by his commandment that she went to Jerusalem and there diligently and with great devotion visited all the holy places: the place where our blessed Lady was greeted by the angel Gabriel; the place where our Lord was born, baptised, preached and performed miracles; the place where he was mocked, crucified and buried; and the place where he ascended into heaven. And at different times she also visited many saints' shrines in her own country and in other nearby countries: in France, Italy, Spain, Naples and many other places.29 After these holy pilgrimages she lived the rest of her life in the city of Rome.

Five days before Saint Birgitta passed from this transitory life, our Lord appeared to her in her chamber before an altar and, with a merry countenance, said to her:

I

have not visited you with consolation during this period

because it was a period of probation for you. But now that

you have proved worthy of the test, continue in the way you

have begun and make yourself ready, for the time has come

when my promise will be accomplished; that is to say, you

shall be clothed and consecrated as a nun before my altar

and from henceforth you shall not only be considered to be

my bride, but you shall also be reputed to be mother in

Vadstena. Nevertheless, know truly that you will leave your

body here in Rome until the time when it will come to the

place arranged for it. And know for certain that, when it

pleases me, men will come who, with all sweetness and joy,

will receive the words of the heavenly Revelations

which I have shown

to you and all the things that I have said to you will be

fulfilled. And although my grace is withdrawn from many

because of their unkindness, nevertheless others will come

who will take their place and will obtain my grace. Five

days from today after you have received the sacraments of

the Church, call each one of the persons whom I name to you

now and tell them what they should do and then, held in

their hands, you shall come into my everlasting joy and your

body shall be carried to Vadstena.

This panel shows her altar at Rome,

which Margery Kempe saw.

This panel shows her altar at Rome,

which Margery Kempe saw.

And on the fifth day as specified, she called all her household to her and showed them what they should do. Finally she gave a stern warning to her son Birger and to her daughter Catherine and charged them that, above all things, they should persevere in the fear of God and in the love of their neighbours and in good works. She then made her confession with great diligence and devotion and, receiving the blessed Body of our Lord, was given absolution. And while Mass was being said before her and after she had honoured the blessed Body of our Lord, she lifted her eyes to heaven and said, “In manus tuas domine commendo spiritum meum” — which is to say, “Lord, into your hands I commend my spirit” ( Lk. 2:46)30 — and, with those words, she yielded her soul to our Lord on the twenty-third day of July, the year of our Lord God, 1373 and in the seventieth year of her age.31

The momentous news of the death of this glorious woman quickly went through all the city of Rome and the people came with great devotion to see the holy body and glorified and praised almighty God. Then, accompanied by a great crowd of people, the body was carried to the monastery of Saint Lawrence — as she herself had revealed that it should be — and because of the great press of people, it could not be buried until the second day.

A woman called Agnes de Comtessa lived in the city of Rome and who from her birth had had a very foul, deformed and enlarged throat. Before Saint Birgitta was buried, this woman came with others to the body and, with her own girdle, touched the hand of this glorious woman with great devotion and bound the girdle about her neck. Immediately thereafter her throat was cured by a miracle of almighty God and it was restored to its correct and symmetrical form.32

There was also a nun of the same monastery of Saint Lawrence who had been a close friend of Saint Birgitta during her lifetime. This nun had suffered a grievous stomach complaint for two years and was so weak that she had been almost entirely bedridden for the entire time and she rose from her bed in great pain. Rising from her bed in great pain, she came with assistance to the bier and lay by it all night where she never ceased praying to almighty God that, by the martyrs and prayers of his glorious spouse, Saint Birgitta—whose body was there present — she might have such healing of her long illness that she could be with her sisters at divine service and that she might, when necessary, go about the monastery without help. And in the morning her body was healed even more than she had prayed for.33

On the twenty-sixth day of the same month of July, the body of Saint Birgitta was buried in a marble sarcophagus and, miraculously, in the space of five and a half weeks the flesh was entirely consumed and had disappeared and the only things left were the clear white shining bones.34

The body and relics of Saint Birgitta were translated from Rome to the Monastery of Vadstena in Sweden on the fourth Nones of July by Birger and Catherine.35 After this blessed woman Saint Birgitta was canonised by Pope Boniface in 1391 — as is shown in the Bull of her canonisation—a woman of the diocese of Linköping called Elseby Snara gave birth to a dead child with great pain and sorrow. And when, after her great pain, she regained her senses, she humbly prayed to almighty God that if, by the merits of his glorious spouse Saint Birgitta, the child might be restored to life, she would visit the sepulchre of Saint Birgitta. And immediately the infant began to become warm and to draw breath and soon it was fully restored to life and thus the mother visited the relics of Saint Birgitta in the monastery of Vadstena with great devotion and gladness and fulfiled her vow.

About the time of the Nativity of our Lord, some people from Jutland went to sea and a great storm caused them to be driven to a place where the water was very shallow and there their ship was stranded. They stayed there a week in great hunger and cold and could not move their ship until, at the end of the week, they were about to perish from lack of food and they drew lots as to which of them should be killed to feed the others. The man upon whom the lot fell committed himself to Saint Birgitta with great weeping and, praying for help, he promised that if he escaped this danger, he would visit her at the monastery at Vadstena. Shortly thereafter they miraculously found a great piece of flesh in the sea and when they had eaten it, the sea became so calm that they were able to sail a great distance over the sea to land in a very small boat. But when the man upon whom the lot had fallen was going towards Vadstena to fulfil his vow, he was taken prisoner on the way and was grievously beaten, imprisoned and shackled with many iron chains. He therefore prayed to Saint Birgitta for help and as soon as he had done so, all his shackles and chains fell from him and he resumed his journey towards Saint Birgitta without hindrance and with great devotion.

In the city of Leipzig there was a painter called Henry who, for the great love he had for Saint Birgitta, used to relate to the doctors of theology many things about her holiness and about the books of her heavenly Revelations. Once because of this, one of the doctors was greatly indignant and, accusing him of uttering a new heresy since he was speaking about the books of that old married woman, said, “I will have you burned because of your error.”37 He was determined that this be done and caused the painter to be called on the following day to appear before the judges. At this, the painter went to a clerk who was greatly devoted to Saint Birgitta to ask his counsel and he comforted him very lovingly and advised him to be diligent in prayer to almighty God and to Saint Birgitta. He told him not to fear anything and that they would help him. He also said that he and another priest called Master John Torto — who was also very devoted to Saint Birgitta — would pray to her for him. And so they did. In the morning the painter appeared with great fear before the judges and was immediately examined. Many things were charged against him for a conviction of heresy but by the prayers of Saint Birgitta for whom he had endured that trouble, the simple illiterate layman was so filled with the holy Spirit and spoke so effectively concerning the great high mysteries of almighty God that his adversaries could not resist the Spirit that spoke in him. He was therefore discharged and his adversaries confounded.

Not

long

after this, our Lord took vengeance on the man who had been

the principal cause of the disturbance. One night he went to

bed well and the same night he was stricken with the falling

sickness and died. Immediately his body rotted and became so

corrupt with such a horrible stench that few men dared come

near it and when the body was handled, the flesh came away

from the bones in great pieces. Finally when men refused to

carry him to the grave because of his horrible smell,

certain people whose job it was to clean the vile and

stinking privies were hired to bear the wretched body to the

grave. And after they had done so, they said that if they

had known before that he smelled so horribly, they would not

have carried him, even though they had been paid double to

do so.

Thus endyth the Lyfe of Seynt Byrgette enpryn

ted at Lôdon in flete strete at the sygne of the

George by Richard Pynson prynter

unto the kings noble grace the xx.

day of Februarye. In yere of

oure Lorde God a M.

CCCCC. and xvi.

T

Notes to Text

1Gascoigne, like all the other early accounts, has “Sighryd.” This passage is found in the Paradiso document in the Florentine State Archives written at Vadstena in 1390 by Johannes Johannis Kalmarnensis (Monastero di Santa Brigida detto del Paradiso 79, fol. 3). The acceptance by modern scholars of “Ingeborg” as the name of Birgitta's mother is based on the vernacular life written at a late date by Margaret Klausdottir, Abbess of Vadstena. See Magnus O. Celsius, Monasterium Sko in Uplandia (Stockholm: Wernerianis, 1728): p. 14.

2Acta Sanctorum [henceforth ASS], Oct. 4, 50:377.

3Scriptores rerum svecicarum medii aevi III, [henceforth SRSMA (Uppsala: Edvardus Berling, 1876)]: 189,190; ASS, Oct 4:381C; ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 3. On the island of Öland a stone cross still stands, said to have been raised by Bride in memory of this event.

4The priest who had the vision was likely not the Bishop Hemming of Äbo, Finland, though the latter person played a significant role in Birgitta's life, serving as her envoy to the Pope in 1349.

5SRSMA, 190, 227; ASF 79, fol. 3.

6SRSMA, 190; ASF 79, fol. 3.

7Aunt Catherine, who must then have been very elderly, retold these stories at Bride's trial for canonisation: ASS Oct 4:383E.

8Aunt Catherine also saw a lady who was working with Birgitta as she sat embroidering with golden threads but vanished when she entered. She put that fine piece of work away, preserving it as a relic: ASS Oct 4:384A; Jørgensen 1:43.

9On children's hallucinations, see Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1976).

10In Digby 172B, Thomas Gascoigne corrects the error “Ulf Ulfsson” to “Ulf Gudhmarson,” This is another indication that this version reflects the author's corrections and research to the official vita.

11ASS Oct 4:384F-385A; ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 3v; Jørgensen 1:63.

12See also ASS Oct 4:392E; SRSMA, 192.

13Benedict means “blessing”; ASS Oct 4:387F; SRSMA, 200; Bride uses Augustine, Confessions 3.12, where his mother Monica is told that her tears for her wayward son will save his soul.

14In the Life of Catharine—likely written by Johannes Johannis Kalmarnenensis and sent to Syon Abbey—this scene is illuminated with a drawing of two delicate hands in elegant sleeves plucking a bunch of grapes (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Digby 172B, fols. 36-36v). Thomas Gascoigne has heavily annotated this vita and drawn from it these episodes concerning Catherine.

15ASS Mar III [henceforth Mar 3], “De S. Catherina Svecica, filia S. Birgittae Vastenae in Svecia,” 3:503-531; 515D; Oxford Bodleian Library, Digby 172B, fols. 36-36v. Saint Birgitta's daughter, who oversaw her mother's canonisation, was in turn canonised a saint. See Stockholm, Kungl. Biblioteket, manuscript A93, Processus canonizationis beatae Katarinae 1475-1477, originally bound at Vadstena in Italian materials, red damask with pomegranate pattern, ornamented in gold and silver, lined with green linen, covered with green silk, sealed with four seals. The manuscript had been in the Birgitta Hospital in Rome, was stolen and taken to Krakow in 1589 and restored to Sweden in 1865: Processus seu negocium canonizacionis B. Katerine de Vadstena, ed. Isak Collijn (Hafniaei: Einar Munksgaard, 1943).

16Bride's dead mother and daughter perhaps shared the same name.

17Bride, who had not consented to the marriage, refused to come to her daughter Martha's wedding. Pregnant with Cecilia, the child in her womb said, “Mother, do not kill me.” Bride then dressed and went to the wedding and later Martha became governess (magistra aulae) to Queen Margaret of Norway (ASS Oct 4:388A; SRSMA, 192; ASS Oct 4:469E; ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 3v). See also British Library, Cotton, Claudius B.1, fol. 2, “Fell in one tyme that she was in dispaire of hir life in travellinge of childe. and sodanli there entirde one woman bpe faireste that ever sho saw clothed in white silke. and laide hir hans on all the partis of hir bodi. and als sone as that woman was went furth againe sho was delivered withouten any perell. And sho wiste wele it was oure ladi.” Elizabeth Makowski discusses such vows of chastity as requiring the consent of both spouses in “Canon Law and Medieval Conjugal Rights,” Journal of Medieval History 3 (1977), 99-114.

18SRSMA, 192-193. On this pilgrimage the Cistercian monk Svenung had a vision of Bride, crowned with seven crowns whose light obscured the sun. The sun represented King Magnus and the seven gifts of the Spirit, Bride: ASS Oct 4:398E, 514. Bride and her husband also went on pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Olav in Trondheim, Norway (ASS Oct 4:398A), thus repeating what had been done by Birger Persson and by his father, grandfather and great-grandfather (Jørgensen 1:99).

19Her husband placed his wedding ring on her finger while he lay dying, but she shortly removed it from her finger, saying her love died with him and she wished now to dedicate herself to God: SRSMA, 227; Jørgensen 1:129-130.

20ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 4. Thus does God speak to Abraham: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will show thee” (Gen. 12:1). This was the formula for mediæval pilgrimage.

21ASS Oct 4:374F; ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 5.

22SRSMA, 204-205; ASF Paradiso 79, fols. 4-4v. See Rudolph Bell, Holy Anorexia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985); Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).

23SRSMA, 204-205; ASF Paradiso 79, vol. 4v. Gentian has a blue flower and is of medicinal use.

24ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 4v.

25At Bride's process for sainthood, Catherine and Peter Olavi remembered her work visiting the sick, feeding the poor, washing the feet of travelers, providing dowries for young girls who wished to marry or enter convents, rescuing harlots from their trade, and caring for the dying (ASS Oct 4:392F, 393AB; ASF Paradiso 79, fols. 4v-5; Jørgensen 1:54-55).

26The major vision which prompted her writings came on the shores of a Swedish lake when God said, “Thu skalt wara min brudh”—“You shall be my Bride”—and also told her to consult Master Mathias, her confessor and tutor. At these words, Bride “in corde suo sentiebat esse quoddam vividum, ac si infans ibi jaceret, volvens et revolvens se” [in her heart she felt something as if it were living, and as if it were a child, turning and turning around]. Note that this maternal metaphor is written in the male, celibate language of Latin: Jørgensen 1:137, 278, 284.

27His son, Birger, later gave a chalice to Vadstena with the inscription: “BIRGERUS MILES FILIUS SCE BIRGITTE ME DEDIT AD ALTARE BTE VIRGINIS” with a Gothic Virgin and Child at the base (Andreas Lindblom, “Altar Kärl,” in Birgitta utställningen 1918, Beskrifrande förteckning öfrer utställda föremål, ed. Isak Collijn and Andreas Lindblom (Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells, 1918), p. 31, Plate II).

28The text mistakenly says “twenty-eight.”

29See Uppsala University Library, Ms. C86 in which Alfonso of Jaen gives her pilgrimage itinerary to Jerusalem and her visions, bound with a copy of John of Climacus' Scala virtutum; See also Ms. C89 (the Vadstena Diary) for a chronology of the events of Saint Birgitta's life; Ms. C251 for notes made in Rome and preserved in Sweden concerning Brigittine life and miracles; Curia Generale, O.F.M.: Liber de miraculis beate Brigide de Suecia (Codex S. Laurentii de Panisperna in Roma, 1374); Vatican, Ottob. lat. 90: Acta et processus canonizationes S. Birgitta de Swedia, 1391; Stockholm, A14: Acta et processionus canonizationes S. Birgittae de Swecia.

30Thomas Gascoigne, Bodleian MS Digby 172, fol. 37, notes that she died on the trestle board on which she customarily ate and wrote her books, although Sister Patricia, O.S.S., Vadstena, considers that this is an embroidery upon the truth. It is still in the Casa di Santa Brigida in Rome, pieces of it treasured in reliquaries. It thus supported not only her book but also her body, conjoining flesh and blood with parchment and ink.

31British Library, Ms. Julius F.11, fol. 254, notes that she died on the day after the feast of Mary Magdalen (ed. Cummings, p. xvi). Catherine of Sweden then became abbess of Vadstena and negotiated the papal bull for the Ordo salvatoris and the canonisation of her mother—and became herself included in the process (SRSMA, 241-244).

32Codex Saint Lawrence in Panisperna, fol. 23; ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 6v.

33Her name was Francesca Sabella (Jørgensen 2:303) and as Francesca di Panisperna, she would be a witness at the process (Codex Saint Lawrence in Panisperna, fol. 23v, Vatican Ms. Ottob. lat. 90, fol. 1v). The healing from a stomach disorder mirror reverses Birgitta's terminal illness from a stomach disorder.

34Her body was garbed not as a Brigittine—a habit Bride never wore—but as a Poor Clare, as if she were a member of The Third Order of St. Francis: she normally dressed in black and white, the attire of a widow. The sarcophagus in which she was buried survives today at Saint Lawrence in Panisperna; it is marble sculpted with putti, little winged cupids. Catherine, her daughter, was prepared to boil the cadaver with aromatic herbs to render the bones clean but found this unnecessary (SRSMA, 224).

35On their journey, Catherine and Birger stopped at Gdansk before proceeding on by way of Söderköping to Vadstena: ASS Oct 4:460A, D; Mar 3:513B. The miracles—both in Rome and Vadstena—justified Catherine's return to Rome to negotiate her mother's canonisation as a saint. While travelling through Prussia on her way home, Catherine became ill and died at Vadstena on the feast of the Annunciation, March 24, 1378. Miracles similar to those associated with her mother were also attributed to her (ASS Mar 3:518B-519).

36ASF Paradiso 79, fol. 7 mentions also that the mother gave a wax image of her child an ex voto to the shrine.

37In actual

fact, some members of the Brigittina Order—among

them

Johannes Johannis Kalmarnensis—claimed

that her Revelationes should be given the same credence as the

Gospels. The 1433 Council of Basle determined that this

claim was rash, untrue and inadmissable but it did not

impugn Birgitta's sanctity, canonisation, cult or Rule. See

Eric Colledge, “Epistola solitarii ad reges: Alphonse of Pecha as

Organizer of Birgittine and Urbanist Propaganda” Mediæval

Studies 18

(1956): 19-48.

Indices to Umiltà Website's

Julian Essays:

Preface

Influences

on Julian

Her

Self

Her

Contemporaries

Her

Manuscript Texts ♫ with recorded readings of them

About Her

Manuscript Texts

After

Julian, Her Editors

Julian in

our Day

Publications related to Julian:

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a

page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern

English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are

in red, Julian's in black, her

editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

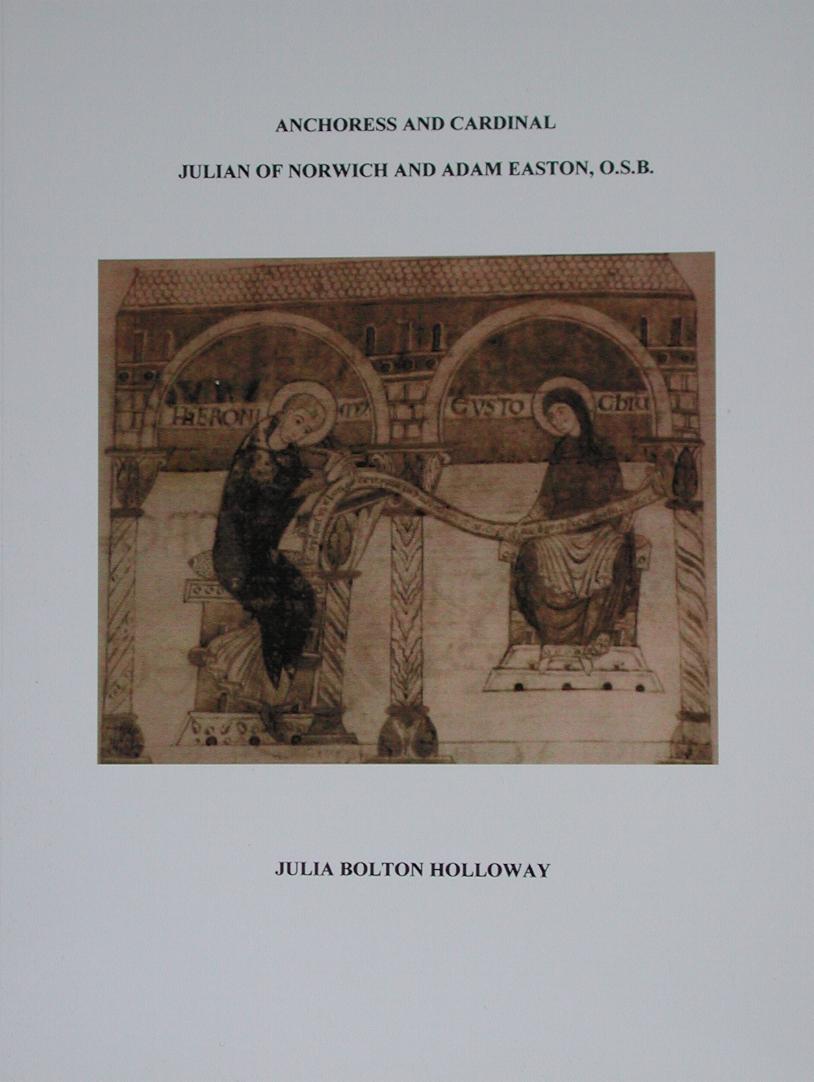

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY | ||| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF LOVE || HER TEXTS || HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM || THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY || Originally published, Peregrina Press, 1991