MOSAIC, PART I

Amidst low-lying

sea marshlands, level horizons rises the town of Rye. It has

been an island with a causeway approach but now the sea has

retreated, has left it cast up like a drowned body on the

shore. In the centre of the town is a church. Aligned with

the high altar swings the great pendulum of a clock

suspended from the tower. The light, flickering through vast

windows of myriad-coloured leaded panes, gleams on the brass

nodule as it swings across the flagged floor, leaving a

moving shadow as it attempts to trace the passage of time in

our world.

The

sun glints on their gilt and daily revolves around their

shadows on the grey stone wall. At night the moon achieves

the same phenomenon but with a colder, lesser light and to a

different regularity, while the sea tides wash against the

land walls to the south.

Man

measures his time by the juxtaposition of but one of many

earths, with but one of many suns and but one of countless

moons. He attempts a minute imposition of order upon matter

in a universe created or existing from the shifting of

atoms, continually combining, splitting, fusing,

disintegrating, passing back to less and forward to more,

beyond the mere sphere of man-measured time, beyond this

puny map that man charts for his petty convenience. He

creates Books of Hours and Shepheardes Calendars. The stars of other

worlds are visible, but do they see or do they care?

March

24, 1962

Who

am I? I ask who I am.

I can

ask the question. A quest. I can seek the answer. How? Thus.

In a diary. It shall not be a formal tale, beginning,

middle, end. No one lives so. But it shall be a grasping of

glimpses of memory, a collection of the make-up of a

personality, a portrait of light and shadow, myriad brush

strokes of variegated colour, a disorderly mass - for such

is reality - and such is time - and such is life.

Another,

such as I, wrote once in her journal:

What sort of diary should

I like mine to be? Something loosely knit and yet not

slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace any thing, solemn,

slight or beautiful that comes to my mind. I should like it

to resemble some deep old desk, or capacious hold-all, in

which one flings a mass of odds and ends with out looking

them through. I should like to come back, after a year or

two, and find that the collection had coalesced, as such

deposits so mysteriously do, into a mould, transparent

enough to reflect the light of our life, and yet steady

tranquil compounds with the aloofness of a work of art.

Virginia Woolf, A

Writers Diary,

April 20, 1919.

In

the beginning of the river of my time I lived near Rye. Then

I left England, came to California. I have been unable to

return. So this is a tale of exile, a mosaic of broken

geographies. Ithaca remains unfound. Though Italy has been

visited. And Mexico. So expect far-flung backdrops to my

tale, picture an Elizabeth and non-Aristotelian drama, with

rapid scene changes from Belmont to Venice and Venice to

Bohemia and Bohemia to Illyria and Illyria to Sicilia. For

this is the tale of Perdita. Let it unfold.

March

25

Two

children, a brother and a sister, Richard and Julia, under

an apple tree. The petals of blossom fall steadily and in

the fields beyond the sheep are bleating sorrowfully at the

joyous lambs. We are quarrelling. We are sent to search for

windfall apples for the cook. The apples on the ground are

wasp-gnawed, bruised and rotten. I feel that my brother is

loved more than I. This angers me. I find myself with a

broken stick in my hand beating down on my brother's head,

again and again. The blood starts to run thickly, matting

his fair hair. More and more it comes, running in rivulets

down his face, his neck, while he stands and screams. The

blue eyes are covered with red gore that goes on flowing.

The ugly stick with its splinters and jutting nail is

stained with it. Could not the anger go away and I stop? I

have no further memory of the scene. It ends in my mind as

suddenly as it began. But the guilt and nausea of it remain.

Again,

we are playing. The boy snatches the girl's doll, they

struggle and the doll falls with its porcelain head smashed.

One blue china eye remains open in its grotesque portion of

brokenness while farther away the other lies closed as the

angle has forced the weights even in death to perform their

mechanical function. Hot anger. Then remembrance, as before,

stops.

March

27

'Richard'.

'Shush'.

'Look,

Richard, you owe me sixpence. Don't you remember last night

on the ˜bus? Mummy wants the . . . ˜

˜Shush,

you'll scare the fish'.

˜Damn

the fish'.

'Naughty,

naughty.

Girls don't swear, only boys can'.

'I

don't care. Please, Richard'.

Richard

was silent this time, standing by the water, holding the

line intent. Julia shrugged her shoulders and sat down on

the bank. She joined him in gazing at the telltale red float

suspended amidst the rippling water. A dragonfly whirred by.

And the water reflections undulated on the trees above them.

The girl felt the rippling, reflecting water become part of

her.

Suddenly

the red plastic float started bobbing. The boy stood there

tense, holding his breath. Julia squealed with excitement,

her trance forgotten. Then he hauled the line out of the

water. From the hook hung a gleaming red and silver fish. It

writhed and squirmed, shaking and twisting its body in an

effort to get free. The silver scales flashed and glittered

as it flung itself from side to side.

The

boy jerked the line and the fish somehow loosened itself and

fell back into the water with a splash that sent the ripples

circling out over the surface of the pond. The boy said

under his breath all the swear words that he knew. Julia

almost clapped her hands with joy. To see the gleaming fish

go free was such a funny painful feeling that she had to

catch her breath and then she laughed. The ripples went on

circling over the surface of the sky-mirroring water and the

reflections on the pale green leaves danced.

'Richard,

can

I have a got this time? I promise I won't break your line.

Cross my heart and cut my throat I won't.

'No,

I'm jolly well not going to let a sissie girl like you have

it, so there!'

'Well,

next

time

then? Please. I'll let you keep that sixpence. Then you can

buy hooks'.

'Ohallrightthen.

But

if

you

dare snap that line you'll get it!'

Julia

nodded delightedly as she watched her brother place the

dough bait on the hook, cursing whenever his fingers got

pricked. Then he flung it far out into the water and the

bait landed, making circular ripples around and around,

farther and farther. The girl watched until the last one had

reached the opposite bank. She could barely see it, it had

become so faint. Perhaps there were others that were too

slight even to be seen.

She

clasped her hands around her knees and laughed softly. She

heard the sound of a tractor ploughing up some fallow field.

Streaks of sunlight warmed her back and on her hands she

watched the flickering reflections of the water. She used to

watch that at school, the reflection from sunlight on glass

creeping across the blackboard . . . imprisonment . . . king

john . . . Runnymede . . . 1066 . . . vernal

equinox . . . tradewinds . . . the name, JULIA BOLTON,

carved on the desk lid with her ivory-handled penknife . . .

the smell of ink and cedarwood pencils . . . and stale

cooked abbages along the corridors. She wasn't at school

though. Often she had gazed out the classroom windows and

longed to be by water, in sunlight.

Sudden

flurry. Another fish had bitten. Richard carefully landed

this one as its tail flailed around, its red and silverness

squirming. The boy grasped it tight in his fist and worked

the barbed hook out. He pt it in a tin can. It writhed.

Gradually its struggles ceased.

'Poor

fish'.

'Hey,

Julia! Thought you wanted the rod this tune?'

'Why,

yes. I must have been dreaming. Here. Give it to me'.

He

handed the rod over to the girl. She struggled with the bait

and then stood up to cast it into the water. The first time

it didn't go far enough. Richard jeered at her. The next try

she fumbled and the serpentine line coiled round some of the

small branches. She tried again.

The

line flung out and the bait sank, weighted by the lead shot,

leaving the red float wobbling amidst the circling ripples.

Gradually the float became still. A bird that had been

singing, stopped. The two of them only heard the chugging of

a tractor somewhere far on the horizon.

She

stared at the float. The water around it looked as if

someone had melted down thousand-hued jewels and had put

liquid diamonds amidst the peacock greens and blues and the

muddy browns. Sometimes a breeze would cross the water and

little wavelets would glitter like the myriad scales of

fish.

It

was sometime before the fish bit, longer than usual, but it

was a big one, bigger than any the boy had caught. The girl

landed it with pride and insisted on unhooking it herself.

She felt no pity for the fish now.

'There

you

see. It's bigger than any you've caught'.

'Yeah.

But

I've caught more fish than you have and those two eels'.

'Ugly

things'.

Ann

shuddered. He took the rod out of her hands.

˜You

know, Julian, I think that sixpence is worth two go's'.

'I

don't, so shut up'.

'Okay,

okay.

Keep

your hair on'.

He

looked annoyed and the girl grinned in triumph. He cast the

line again and they waited. The girl plucked a blade of

grass and chewed the juicy end of it, and then reached out

for a blackberry growing up amongst the thorny ramblers. The

trees bowed down over their heads. The water at their feet

rippled and sparkled.

A

spaniel dog came crashing through the bracken and came up to

the girl, nuzzling his nose into her hand. She started to

laugh. The dog barked. But the boy was angry at the

disturbing noises.

'You've

got

to keep quiet, Prince', the girl said, ˜Richard's fishing'.

The

dog went on barking, jumping up and down. He leapt up

against the boy who lost his balance, slipping in the mud.

Julia laughed at him and he laughed, too. He struggled to

his feet with her help. Prince lay watching them, thumping

his tail. He jumped up and barked again, his spaniel ears

flying.

'All

right, old guy. Wait a minute and we'll go for a run'.

He

packed up his home-made rod with care and they set off for

the house. Julia whispered, ˜Don't let Mummy see that mud'.

The boy dashed into the yard leaving his rod and catch in

the stable house. A litter of puppies began to run for his

feet, crying and yelping and rolling over while their

mother, another cocker spaniel, watched the boy anxiously

and thumped her tail on the brick-laid yard.

He

ran back to join the girl. Prince took off and they followed

after, scrambling over the gate and running down the green

sloping field with the wind rushing in their ears. The dog

was far ahead of them. They reached the hedge at the bottom

of the field. There Prince lay on the ground waiting for

them, panting, with his tongue hanging out. Then they

scrambled over the wooden style and walked together across

the next field where the wood began. The dog dashed round

them in circles, barking. Then he ran off and flushed up a

bird into the blueness of the sky, pointing with forepaw

raised.

The

boy tried to whistle as they walked along. Julia laughed at

him. He couldn't whistle very well. He cut a hazel switch

from the hedge with his pocket knife. He beat the air with

it making a sharp, swishing sound. He said, 'Daddy is going

to sell the pups'.

Julia

turned around sharply, spreading out her hands in a sudden

impetuous gesture 'Why won't he let us keep them?'

'Silly.

Because

then

we'd have eight dogs instead of two, then more and more'.

When

they got to the wood the boy led the way up a path they had

not been on before. It was strange coming into the wood

after the openness of the fields. The boughs of the trees

filtered through so little sunlight. The light would come

down in narrow spear shafts gilding the undergrowth and

green bracken and fern. The rotting leaves on the ground

deadened the sould of their footsteps. The dog ran along

shuffling amongst the leaves, snuffling with his nose the

strong wood smells. He dug up a dead shrew from under the

leaves. Julia made him leave it. They ran on through the

woods.

They

came to a sunlit glade which was a crossing of the paths.

They boy turned down another path into the half light again.

There were fungi on the trees, strange toadstools forming

out of the mould on the ground, creations of decay, coloured

like poison. Then suddenly they came into the sunlight and

the open fields again.

The

dog began barking at something hanging from the tree by the

fence. The girl started to climb over the fence and then saw

what the dog was barking at. She screamed out. 'Richard,

what is it?' A black crow rose into the air, startled,

beating its wings. Richard said, 'That's the gamekeeper's

gallows. He hangs stoats and weasels he's caught there to

scare the others away. He picked up a stone and flung it at

one of the decaying weasels hanging on the plank of wood

nailed to the tree trunk. There were dead rabbits, too. One

was fresh. Its fur was still pretty and soft save for a

blood stain on its neck. Its eyes had not yet been picked

out by the carrion crow.

They

walked up to the house. The boy took his fish in to show

off. The puppies gambolled and played in the sunshine.

March

31

I

give the past to the children as a curiosity, a mere

plaything. The importance of my birth exists in the past

tense alone. And there it has the colour and unreality of a

lending-library novel. The useless but bright silver napkin

rings are my children's toys. For today we weave a new past.

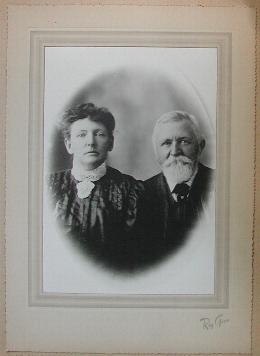

Joyce Bolton, drawing of

Julia and Robin, October 1959

Joyce Bolton, drawing of

Julia and Robin, October 1959

Only

as a diversion to amuse a child is the Pandora's chest of

memory unlocked. As Nanny had revealed to me the bits and

pieces and childhood treasures of her past. My Russian Nanny

kept a vast trunk in our nursery. It was never opened until,

one day, my doll had lost the ribbons for her hair. It was

to replace these that the chest was at last flung open. What

treasures we saw inside: wooden Russian dolls with stiff

mechanic joints and round red-painted circles on their

cheeks, more dolls with peasant rich patterns painted upon

them that fitted one inside the other, generations of five

or seven or ten, a gay profusion of jacquarded cloth,

ribbons and laces, a riot of reds and blues and golds. And

then the gates of Paradise shut. But my plain doll had

scarlet ribbons in her hair.

April

3

Take

with the harsh hands

Water, wine, bread from stones,

Make blood.

They've spilt enough of it for this.

Bread from stones, make flesh.

Blood's been often shed in exchange for bread.

Take with the harsh hands,

Water, wine, bread from stones.

Rivulets of blood shed for creed and bread.

They knew not which nor why nor where

On the barbed wire lies impaled the lacerated flesh.

Take

with the harsh hands.

She

is six years old when her long loose hair is tightly plaited

behind her face and she is first taken to the school. Her

mother is not with her. She is in London. War is raging. The

young child and her brother are boarded with a childless

Scots couple who love them dearly. They live in a Sussex

bungalow filled with fumed oak furniture and which has a

sand pit, an orchard, a tool shed and a green house with a

grape vine, thick and gnarled with age, thrusting up against

the paned glass roof.

The

frail Scotswoman rings the convent doorbell. The girl and

her brother lean close against her skirts. The door is

opened. It is the first time the girl has seen a nun. The

garbed figure whose face is framed by a stiff, snowy coif,

smiles sweetly and bids them enter. They walk along a sunny

white corridor to the parlour. There they are greeted by the

headmistress and shown into chairs. Talk. Talk in waves and

rhythms, incomprehensible. The children fidget. They feel

guilty, knowing they should not do so. The nun talks forever

to their foster mother. When they are ready to leave she

swoops down and kisses the girl's forehead. The sharp coif

feels uncomfortable but the kiss is gentle. There are

butterflies in the walled garden beyond the window. A bell

chimes slowly. The interview is broken off and they leave,

the girl and her brother holding hands as they go down the

stairs from the grey stone doorway with the Latin

inscription on the lintel.

PAX INTRANTIBUS

SALUS EXEUNTIBUS

BENEDICTIO HABITANTIBUS

Words in a strange language, left an unsolved mystery until, some years later, the Latin mistress introduces her first year pupils to the ancient tongue by helping them translate the many classic mottoes to be found throughout the school grounds on mossy stone lintels and baroque Italian archways. Then and only then did she decipher:

Peace to those who enter here

Salutation to those who leave us

And blessings upon those who abide

here

Elsewhere in the garden of Paradise it

said,

SALVE ATQUE VALE

April 4

She remembered, in Italy, the naked

child standing amidst the wheat. A scene glimpsed briefly in

the golden landscape from a swift moving car. The child's

mother stood apart, her hair bound in a blue cloth, grasping

the grain with one hand and the swiping sickle in the other.

The father was drinking from a cool amphora. The parents'

faces squinted in the bright noon light. Their backs were

bowed, their faces glistening with runnels of moisture.

But the child was free, stalwart and

golden, in his hand a sceptre of wheat, on his face a look

of kingly triumph. Then the scene vanished as it had come,

eclipsed, glimpsed, eclipsed through swift near trees. The

car sped onwards. The glance at vital myth gone, save for

the image of memory.

April 5

A gathering on the lawn. Tea cups

clattering elegantly in saucers. A garden party at

Powdermill House in those halcyon days of the late thirties.

The guests, writers, dancers, an M.P. or two, a sculptress

with red hair, a dame and a poet. Quite one or two county

families. Husbands, wives, a few small children. A mother

with her child, a daughter in flounced white silk, a mere

baby of four months.

Dame Lilian Baylis was old, with

little life left of all her magnificent years as founder of

the Royal Ballet, the English National Opera, the Old Vic

and Sadler's Wells. Her eyes were dim. Her legs, dancer's

legs, were tired. She took the small girl on her lap. The

baby was a chubby thing. It smiled at her. Dame Lilian

declared, and in a manner becoming to her theatrical career,

'I am your fairy godmother, little Julia. I predict that one

day you, too, will be a great dancer. You will charm the

world with your gift as you now charm an old lady with your

youth'. The baby waved its hands solemnly in the air. Her

mother felt a burst of pride. Dame Lilian had said . . . Her

daughter would be . . .

Dame Lilian died within the year. The

theatrical world mourned. A mother determined on a ballet

career for her little daughter.

The war came. The girl grew older.

When the wireless filled her parents' London drawing room

with concert music the little girl pirouetted and danced

upon the Aubusson carpet. For hours she danced in joy of

untrained movement. The magic times would come when the

music came inside her, her dance and the music came

together, knit and were married, became one and the same.

Then she was happy. The mother watched and planned. The

girl's father took her to see the Sadler's Wells Ballet. The

little girl thought that when

they got there everyone would get up and dance, even she

would dance. Her disappointment was bitter that the only

dancers were those on a stage far away. That a platform

divorced them from the beholder, they were seen above

adults' head imperfectly. She began to cry. To the

consternation of her father.

Her mother enrolled her in a dance

class. Her Nanny took the little girl. They waited in an

anteroom where the other pupils sat around and talked. A

girl came down some stairs singing. The little girl stared

in disbelief. Then they went into the practice room. She

left her Nanny behind. The pupils lined up down the room.

Some were at the barre. She found herself in the centre row.

The instructress in a black leotard anounced the arrival of

a new pupil to the class. Then she told them to start.

Julia thought she was meant to dance

as she had in front of the wireless upon the pale Aubusson.

She commenced to twirl and skip and pirouette. Then a hot

blush mounted to her face. The others were not doing this.

They were not dancing at all. They were stiffly raising

their arms and placing their feet awkwardly into odd

positions. The girls at the barre were swinging their legs

in front and behind. She was supposed to do this. This was

not dancing! She stumbled to a stop and stood, watching in

panic, hot shame in her heart. She remembers no more of this

incident.

Other such dancing schools swim before

her memory. Gleaming oak polished floors and bronze slippers

with a tiny diamond on each, the clean handkerchief, white

silk frilled dress, white socks, silk ribbon around the long

loose hair. The other children. The teacher in shimmering

mauve watered silk and long jangling strings of beads and

the light falling through great mullioned windows. Or the

ballet school with its barre, the great grand piano, the

William Morris wallpaper, the room that must have once been

the drawing room of the large house. The windows that looked

out onto a tangled, ill-cared-for garden. Her embarrassment

when she could not hear the teacher's instructions because

of her war-deafened ears. Her fumbling and stumbling,

perspiring, cold and clammy in her black short silk practice

frock. 'Must I go, Mummy? I hate it'.

It was when the war was over that her

mother decided to take her to London for an audition. She

was to miss school for that day. Had she practiced her

dances? A large bouquet of flowers was gathered from the

country garden and taken with them on the tedious train

journey. Their scent filled the closed carriage. The dingy

London streets. A ride in a red bus. The square of Convent

Garden filled with flowers and vegetable stalls and hawkers.

Dank concrete stairway. Asking information of where to go

from a cross-looking man. Being ushered onto a vast stage.

Something about it being a quarter of a mile lone.

Ghost-like hanging scenery, a greyness over everything.

Workers shifting pieces endlessly. Staring into the curtain

behind which, that night, would be countless faces, staring,

talking, fluttering, waiting for it to lift.

Miss Ashburn, the director, came up.

Graciously accepted the flowers, talked to the mother, while

the daughter stared at another girl, self-assured, jolly,

waiting with her mother for their turn. 'Now show me what

you can do, dear'. The girl startled, turned back and

mumbled something about a waltz. 'All right, show me your

waltz'. She started to waltz stiffly across the stage away

from the figures of her mother and the director. 'Wait! Come

back here! You'll get lost, dear'. She came back feeling

silly. 'Now show me your basic steps'. She fumbled through

them. At the ballet school her pupil teacher rarely taught

her because she could never hear her instruction and so was

left to stare into the ruined garden for an hour and then

return home. Miss Ashburn looked worried. Then she examined

the girl's feet, making her stand against a great theatrical

bed of blues and golds to be used on one of the sets that

night. She turned to the mother and told her the child

should continue to go to the local school, come back later

when had made some improvements, thanked them again for the

flowers. The other mother and her daughter smiled as they

made their way towards the exit.

Outside Julia begged her mother to let

them stay and see the ballet that was being given that

night. Her mother became angry. They had spent enough money

as it was, she said, and they had to catch the train. The

girl's hands reeked from having held the flowers so long.

They were empty and displeasing to her. Her mother did not

smile and for days she remained cold and distant towards the

girl.

April 6

To my Icarian Uncle

Spitfire pilot of the R.A.F.,

Tortured mind.

I haven't forgotten how you once

described

The land falling upwards to your

plane,

In a sickening landslide reversed.

My brother won't forget how you

Cried when he shot his toy gun at you.

You

Were the first adult he had ever seen

cry.

You had been his hero.

He won't forget either the day you

killed the dog,

Breaking its back, and had tried to

set the house

On fire, merely because we had told

you what

We saw the day when they shot

The German plane down in the field by

our house.

We were going to show you as a

curiosity

The hole it had made. We told you how

the pilot had

Died, screaming in flames, the

twisting of metal in heat.

And so the sea-darkness of nameless

emotion had risen

With a deadly lurch, slapped violently

against your

Identity, and you had drowned in

lunacy.

Children are callous.

April 8

Psychology, literature, history, all

were to be studied in an attempt to plumb human personality.

In psychology a great deal of time was given to Pavlov's

salivating dogs and also to tests which attempted to reduce

personality to a matter of numbered statistics, but beyond

the theoretical formula that personality = heredity x

environment, that field of study proved unprofitable. The

wrong direction had been taken and it led nowhere.

Literature was of more value. I found that the writing of

man mirrored man. I read interminably. But I was seeing a

reflection, a shadow of the real thing. History disappointed

me because it failed to tell of the people involved within

the great historical actions. It is not equipped to do that.

It has a falseness like that of the analogy to the human

body that Bacon makes out to be the commonwealth. The

working of the historian tends to depict those human traits

that are at the bestial end of the scale rather than the

angelic or even humane. Its spirit is the spirit of the mob.

And I wanted to believe in free will. Neither psychology nor

history gave me rein for this. Literature could. I read

Milton, Milton who believed wholly and entirely in the Free

Will of Man. Milton who wrote of English flower-filled

meadows, whose words to me became truth.

In college we had a friend, a bearded

Sicilian who majored in philosophy. He had formulated a

theory of determinism and he would walk with us for blocks

working his theory out verbally. With words and concepts he

built a fantastic, invisible structure which had,

nevertheless, its own reality. There was only one argument

with which I could attack it. And that argument I purloined

from Milton.

His theory refuted predestination. The

past can not be changed at all nor by any means. The past is

irrevocable. But the present, determined by the past, is

also the agent of future determinism. And so, in a sense,

having the power to determine, although determined, it is,

paradoxically free. A person living on the narrow thread of

the present whose personality is supposedly determined by

what has gone before yet has the power and the freedom of

being himself the agent for determining the act, who makes

the choice. For all acts are based on the choice of the

individual even when it is the choice of not choosing; of

letting events continue without acting is also a choice. And

the future does not exist. Only the present with the past

behind it, the influence of the past on it, is real and has

power. Each individual is the agent of determinism. Each

individual has the choice of how he will determine the

future. He is the determining agent himself and therefore he

is free. He is, as the existentialists say, chained to

freedom.

For many hours we listened as this

argument was unfolded by my philosopher friend, walking in

the streets, watching his sensitive face while we heard his

words, walking in sunlight and starlight, beneath trees and

clouds. The 'professor' as he was called by us, would take

us by the power of his words beyond thoughts of things

around us. We would live in an intellectual kingdom divorced

from the petty reality of physical things. We were beyond

Plato's cave and in the spiritual sunlight of which that

great philosopher speaks. And then we would have to return

home.

Of what is a human? I am yet too young

to know. I tried to find the answer in the poor deceptive

mirror of the printed page. I should have gone out into the

streets and found him there. I went out to look. But I found

not people but a mask on the face of every man. Each seemed

to say, ˜This is what I wish you to think I am. The real

'I', I do not wish to show. It is not what I think you would

care to see. Or if you cared to see it and did, you might

harm me. Therefore to protect myself and live I wear this

mask'.

I was intent on breaking the mask. But

I never could. I knocked on the doors of homes and was shown

the front room which was clean and garnered but the back

room with all its delights and individuality was not shown

me. Until I fell headlong in love.

California is six thousand miles away

from Sussex. It is dry and dusty and has a different beauty.

There I knew the longing to find primroses and to hear the

cuckoo song of spring and watch the trees burst into leaf

and be April with its showers and blossom. Once, twice,

three times I knew this and I thought my heart would break.

But in the third spring someone would come and say, ˜Let's

go and have coffee'. Over cups of coffee and the cadence of

juke-box music I knew that he knew that which was in my

heart. So I learned to know a person. The world became a

thing of fruitfulness, of completeness.

I had not known before that it was

this that opened the door, that allowed one to pass beyond

the anteroom. I had laughed at love. All the poetry of the

world until this has been as valueless fool's gold when it

spoke of the power of love. But now I could no longer laugh.

I, too, belonged to the confraternity of lovesick poets.

Although these poems I hide. Only he has read them.

April 9

Ferdinand/Miranda

Game and play

Of love and

Chess

Castles overthrown, queen captured,

Upon the motley board

Alone.

The martial red awaits the move.

Let me kiss you.

Do

you mind?

Do you enjoy

Cherries

from off the laden boughs of summer?

Do but bid me get them.

Ah,

I forgot your pawn.

And now it is your move.

Miranda, though art most lovely,

See, the sun makes rainbows of your

hair.

It glints like the light on

New

minted pennies.

Let me give you cherries.

But see how

The

black rook advances.

Ah, my king.

So,

it's checkmate

Alas.

But

do come gather cherries

Before they fall and fade.

April 10

Paestum

We had quarrelled. No, we had not

quarrelled. And that had made it all the worse. The anger

had not broken surface, had had no outlet. I was full of it.

The sun was too hot for our child so

my father stayed with him, took care of him at the

wine-shaded albergo where we had lunch. My husband had not

been eager to see Paestum. Indeed, in a sulk, he had caused

us to miss the bus the day before. Now we were here. An

extra night in southern Italy. My father did not reproach us

for our absurd anger and the added expense. I apologised. My

husband did not.

The anger and the heat grew worse. We

walked in the blinding sunlight towards the entrance. The

plain now only had ruins, a handful of habitations, the

sparkling bay and expanses of infertile and dry weeds, wheat

and rye mutated back to wildness. The wealth of Paestum was

obliterated by disease, its population long gone, its

livelihood lost. Even its roses famous in antiquity were now

wild, the simple petaled tudor form one sees in English

hedgerows, cultivation barbarized.

Between squat, powerful columns we

walked. But we could not walk in harmony. Rage filled me.

The last thing I wanted was to be close to him. No enjoyment

of classic Greek could come in his presence. While he stood

gazing, I slipped away. And as I left the anger left me. Had

it come from him, then, and not from within myself?

I was free. I no longer cared where he

was, what he felt. I saw a butterfly, golden, tawny, flit

among the stones. Towards the Temple of Neptune I went, like

a child, wandering at the dawn of time. The rosy shafts

gathered me to their epicentre, and there I stood, gazing at

the alternations of warmth, sunned stone, tawny tawdry grain

and sea water glimpsed briefly.

Temple of Neptune, Paestum

Temple of Neptune, Paestum

Then I tried to populate the vast old

city, calling up those crowds of merchants, haggling over

their shipments, Bassanios, Gratianos. They refused to come.

Had the city always been dead, ruined since time began? But

the columns lived, their tension spoke of power and warmth.

Architecture beyond ornamentation, the marriage of art and

science, with its own meaning, its own life.

A lizard then suddenly scuttered up

one side of a column right before me. I had touched its

sandstone, sun-warm surface. The lizard stopped scuttering

and hung there, its eyelid blinking slowly.

Then I knew the ruins lived. When the

temples were newly built, unruined, lizards such as these

had climbed their shafts to hang and bask in the golden

light. Paestum became alive. A bridge was made in time, life

and stone co-mingled.

Then I saw my husband come towards me.

I had forgotten the emotions of the morning and now all

their power was gone. He, too, had forgotten. And he smiled.

All the way home he could not stop

talking of Paestum.

April 11

Prospero/ Miranda

Julia's father, John Robert Glorney

Bolton, was the son of an Irish painter and portraitist,

John Nun Bolton. Julia scarcely knew him. The war separated

Julia and Richard from their parents, its aftermath brought

work habits that kept Glorney in London and the children in

the country. Julia's father was mostly a stranger to her.

But there were moments together. One

in particular, a remembrance of October sunlight, the

wallflowers growing against the brick in warm golds and

brown's and Julia's father putting a book in her lap. She

was to read. The print was eighteenth century and at first

she stumbled over, then mastered, the long s's like f's. The

binding was luxuriant old leather and the pages, turning,

made the sound of subdued waves of the sea. It was a volume

of Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

She remembers, too, on a winter's day,

his reading to her Plato's tale of the death of Socrates.

Then she understood death, the extinction of intellect, the

finis of

identity. Socrates had a way in her young mind of getting

mixed up with Gandiji. And Glorney Bolton was one of

Gandhi's biographers. Julia's father could not paint, but

yet he had not denied his father's calling. After Oxford he

became a biographer and journalist, the portrait painter

whose palette held words for pigments.

April 12

Sometimes, perhaps, you have seen a

dragonfly born, its metamorphosis. It drops its last sheath

and like a prism or diamond cut glass takes on the myriad

colours of refracted light, but above all it is blue. It

alights on some rock or leaf and there in the sunlight

unfolds itself and takes on strength and life from the sun.

The dappled light of the pool flickers around it, and its

wings stretch and tremble and it waits for full strength to

come.

John, as he watched her, thought that

Irena was like a beautiful insect, her character unfolding,

continually unsheathing itself. He should, perhaps, have not

married an actress. She made him feel clumsy, like a

lumbering bear, or like a heavy bumblebee around a delicate

flower. Even now he felt a blush rising, the heat of shame.

As a child he had felt remorse at touching the weak

dragonflies' wings and crippling them before they attained

their full strength.

She was watching him, standing there

and behind her the firelight flickered. It was a coal fire

and amongst the orange flames was one blue one, that

suddenly flared up from time to time. She stood there, tall

with her hands on her thin, lithe waist. She raised herself

as if she would, in stretching, reach so high that she would

finally take off in flight.

She wore vivid blue chiffon that

draped and fell away from her new forming wings, growing and

yet not fully strong. Her hair was lustrous and dark like a

bird's wing and smoothed back over her head without a

parting. The smoothness accumulated in the shining coils of

a braided coronet. The firelight glinted in the dark mass

and caught red-gold lights. Her pale neck reminded one of a

swan's, its fairytale, exotic quality.

Irena Whitecastle, besides being

beautiful, was also an actress of genius. She sighed. The

sound was like water rippling over a quiet country pond

which glinted in exotic and alien colours. She made even the

elegant French style room of creams and golds seem but a

foil to her brightness. 'John', she whispered. John

Whitecastle was captivated, he was eternally captivated.

'John, say goodnight to the children for me. I'm too tired,

and don't stay to tell them stories. Come back soon'.

John Whitecastle kissed his wife and

did as she bade him. Until he was out of the room he felt

like a clumsy oaf. But John Whitecastle's colleagues felt

differently. They knew him for an outstanding surgeon. Away

from Irena and under the great chaste lights of the

operating rooms his hands were as sure and as deft as the

movements of a dancer. It was only with Irena that he felt

this sense of inadequacy, of clumsiness and a lack of

graciousness.

John Whitecastle went to the

children's room. Little John and Elizabeth were asleep.

Their faces rested on fair pillows in complete innocence.

John wished they were awake. He worried because they were

pale and longed to take them to the countryside. He wished

to give them more the feeling of a family. But his hours

were very long. And his wife was an actress. Irena acted so

many roles that she seemed to forget her own. John did not

know what she really was like. He had never known. She

seemed to have no past, no being, only an exquisite exterior

and personalities that she assumed and discarded as she did

her theatrical costumes and make-up. The directors would

shout at her when she explained that she needed time off

when she was carrying little John and then Elizabeth. She

did not like child bearing. He should be grateful that she

conceded so much. Little John's face was sensitive and thin.

Elizabeth got her way by screaming and crying. Neither child

really knew how to laugh. They were taken care of by a hired

nursemaid who took them for walks in dreary city parks and

by a governess who prepared them for boarding school. John

Whitecastle felt suddenly weary.

When he went back to the room with the

flickering firelight he started to tell his wife about an

idea he had. But Irena was telling him something at the same

time. He stopped to listen to her, but in his weariness he

heard only her voice and did not follow the sense of her

words. As Irena talked she glided around the room, her

chiffon drapery floating around creating endless patterns

against the pale gold wall behind. She captivated him. Once

when he was a child he had read a story by Anatole France of

a monk who had renounced all evil, but who, when he was in

prison for his goodness, was released and led into the

fields of day by a being so beauteous that he fell down and

worshipped. And the being was Satan. Irena was like that

beauteous being, John though, but without the evil, only the

good. All through time man has coupled beauty with the good.

Her movements were liquid music. They

were studied and yet effortless. Everything she touched and

did and saw became a work of art. And always she reminded

him of beauty remembered from childhood of the new born

wings of dragonflies, of the hypnotic gaze of an exotic

snake amongst the bracken, of the jewel eyes of a toad and

sometimes of the purity of falling drops of water catching

sunlight from a lone angler's rod cast amongst the osier

reeds.

Irena's words came floating to John

Whitecastle's ears. They were beautifully modulated, they

came as the sounds of summer come drifting over fields of

golden wheat. Irena was an exotic poppy, gypsy red and

scarlet velvet amidst the golden sheaves. John Whitecastle

spoke also, forgetting what his wife was saying, not having

heard her words.

'Irena, come here by my side'. She

came and he could smell the perfume she wore. It was warm,

vibrant, expensive. She curled around his feet like a feline

creature, a magnificent princely cat with all the elegance

and superiority of that animal.

'John!' she laughed like rippling

water. 'I am sure you did not hear a word I said'. She

propped her chin on her hand, her elbow resting on the pale

carpet. Her eyes looked at him. The position she assumed was

one that children like, but then again she was far from

being a child.

John went on talking into her eyes.

'Irena, the children need to go to the country. We can go to

my parents' place. Do you remember how I put cherries over

your ears? They will be ripe soon and I can get a holiday.

Garth, you know, who was at medical school with me, can take

over the practice for a week or two weeks perhaps. Can you

get away from your theatre? It would the children so much

good'.

There had been the time he had taken

her there. She was like an exotic plant in his parents'

Georgian house amidst the castle ruins. The cherries were

ripe on the trees that were trained to the old walls. He had

hung the red fruit over her ears. They looked well on her,

better than the jewels he gave her. But she disputed that

point. She loved rubies and emeralds and diamonds. And she

loved large, even vulgar stones. John's mother had been

distressed when Irena scorned the old- fashioned Whitecastle

tiara and the heirloom necklaces and brooches. She had, it

is true, had some of these reset and these she seemed to

like better. A visit to Cartier went to her head like wine.

She never liked the country or simple pleasures. Her eyes

were blind to the loveliness of dappled light on water and

the harvest gold accented with the scarlet of poppies. John,

who had a good seat on a horse, was surprised to find that

Irena could not ride well. Elegant as she was, she could not

ride a trotting horse with grace. She disliked horses. John

would be disappointed. But she did love the exotic peaches

brought in from the sunny south wall where they were grown

so carefully. She only liked expensive, exotic things.

'I know Garth will take over for me',

John Whitecastle found himself saying. John had gone up to

the cold north to medical school. Edinburgh had the finest

medical school in the world. And both Garth and he competed

for the top honours. They were the most brilliant students

of their year, it was said. They competed in a friendly way.

On the surface there was friendship but underneath each

desired to do better than the other. Now both were

celebrated Harley Street surgeons. They had exchanged the

Edinburgh of delicate Gothic pinnacles for the London of

iron railing and fog, the Thames at low tide and nursemaids

wheeling perambulators in parks where the very trees were

covered with soot.

Garth was a Scot. He was tall,

dark-haired with intense blue eyes. He had gone through

medical school entirely on bursars because his parents were

too poor to pay for it. John Whitecastle was also dark, a

Norman. His eyes were hazel. His family had estates in the

south and he grew up amidst the fields and meadows where

sheep were shorn of their wool and where golden wheat was

reaped and harvested. Skylarks soared and sang. The sea was

not far away. In the summer they would swim out in the great

rollers and in the winter the sea mists would come inland.

During the holidays, as a student, he would ask Garth to

stay with him. They would follow hounds, a sport which the

Whitecastles introduced to Garth. John's father, a stern

country Justice of the Peace, had also been Master of the

Fox Hounds for years. In the summer John and Garth would

swim in the sea, rejoicing in their prowess.

Irena answered. John suddenly felt

again that she acted. Her attitude changed. Always she

changed. Her companions in the theatre world were like her

in that way, too. Of all the roles they played he never knew

which one was their real self, by which one he could judge

their real attitude toward things. Likewise he had never

known, he felt, who the real Irena was. His eyes followed

her. She stood up elegantly. How could she get up from that

position and still be graceful, he marvelled. As she spoke

in reply she lighted a cigarette in her long holder. John

realized that again he had blundered. He should have lit it

for her. Once he had laughed at her because he though the

affectation of a cigarette holder was absurd. The next day

she had bought a jewelled one, one that was very expensive.

'John, darling', she said. ˜I wish you

had been listening earlier. Peacock, you know, the young

playwright with the auburn hair, has just written a play for

me. We start rehearsals Monday. I

can't possibly leave, at least not for some months. You

know, it's a terribly beautiful play. Peacock writes lines

that are poetry. And he wrote the main part with me in mind.

I have the script over there. You must read it, John'.

'I wish Peacock and his stupid play

were at the bottom of the sea. Listen, the children need to

feel a family around them. It isn't fair'. John knew she was

angry, knew it was no use. The light from the coal fire was

dying down. Irena stood there. He knew he could never have

his way with her. The play would be perfect, like some fine

rare gem, because of her acting. Her acting was like the

brilliance of an enduring diamond and yet it constantly

changed, like the unsheathing of a dragonfly. Never was it

quite the same.

John would go backstage to his wife's

dressing room, the star's dressing room, to tell her how

wonderful he thought she was. But so many people would be

there whom he did not know, all of them crowding around

while she removed her make-up with blobs of smearing cold

cream, yet managing to look beautiful all the while. She

would talk to them, her manner changing with each person.

She introduced them to John, Mr So-and-So, the Director,

So-and-So, the critic, So-and-So, of the cast, and yet some

other vague personality. John did not belong to their crowd.

But she reigned over them all. John wondered whether she was

sincere, whether she could ever cease acting with them or

with him. After all, the word 'hypocrite' came from the

Greek for actor.

John Whitecastle thought of his

children. 'Very well then, Irena', he heard his voice saying

into the silence of the room. 'I shall take the children to

the country. I shall go down for only three days but shall

leave them for as long as they like it. My mother will love

to have them'.

The next weekend John left London

taking with him Elizabeth and little John. The two children

seemed so forlorn to him as they stood there by his side,

amidst the swarming railway station crowd, beneath the steel

girders of Edwardian functional architecture and surrounded

by the noise of raucous loudspeakers and the shunting and

letting off of steam of the engines. They were afraid to go

near the great engines and talk with the driver as he would

have done in the hope of a ride on the footplate. But they

had fun those three days. John tried to teach them to swim

in the sea. They took walks together in the countryside. He

left instructions that they be given riding lessons. They

went fishing all three. And John Whitecastle even heard his

children laugh.

His mother organized a tennis party

and John played several sets. Garth and he had played a lot

together. When he did not play he sat with Elizabeth. One

day she, too, would play tennis dressed in white linen. One

day, too, he would see Elizabeth's daughter. After they, at

last, released him from the asylum where he had been placed

on a charge of insanity. One of the evenings they got into a

discussion of Peacock's plays.

It was with a light heart that John

Whitecastle returned to London. The country had done him

good. His children were happy. He felt relaxed and full of

new vigour. He longed to see Irena again. It would be good,

too, to get back to the dramatic moments in the operating

theatre under the harsh white lights, where he could feel

his skill as a surgeon assert itself.

He mounted the stairs to their flat.

It had been late evening when his train got in and he had

taken a taxi so as not to lose time. He knew Irena would be

home from rehearsals. Perhaps she would be in the French

drawing room arranging a bouquet of expensive flowers in a

vase. His mother had had sweet smelling sweetpeas in every

room when he was there. He liked to see women arrange

flowers.

He unlocked the door of their flat

with his latchkey and walked down the corridor. It was then

that he heard the voices. Irena's and another's. Was it

Garth's or young Peacock's?

Something within his head gave way. It

was like blinding light and yet it was darkness. One side of

him was perfectly aware of the turmoil of the other, of the

wildness of the action, but lacked control, had not even

desire to control, but stood aside, apart, as an onlooker.

It was aware that the other part of him picked up the gun

kept in the bureau drawer and walked over to the bedroom

door, opened it and shot him. The whole thing seemed to be

perfectly and coldly rational. What was abnormal was that

the action was devoid of any emotion. With the explosion was

a scream of Irena's and then nothing for a long time except

the glinting, prismatic light on the unfolding of a

dragonfly's wings, strengthening itself in the dappled

sunlight that flickered over the ripples of a country pond.

April 13

A Poem for my Son

You were born when the golden

Wheat dancing in waves to the wind

Fell to the sickles of farmer folk

And stacked in shocks sunned goldenly

˜Til the wagons came and garnered them

Into storehouse and barn.

And when the rose red apples like your

Silken plump cheeks were harvested

And garnered into winter attics.

And the onions were festooned from the

rafters

And the lavender stripped and

Laid between fair linen in cupboards.

And as winter came you learned to

smile

And the stars smiled and trembled in

the

Sky above vast lands of snow. You and

I

Went fishing for stars.

We hung them round your cradle in an

endless

Sparkling chain and laughed and smiled

together

Until you squalled for food and shook

the chains with anger

And I gave you milk. You suckled my

breast

Lustily and grew strong and

Satiated drew you head away

Looking up and crowing with

Pleasure.

With the spring

We went out into the fields, you and

I,

You tried so hard to say words in our

language.

We gathered flowers.

You grabbed them and my hair.

Do you remember the daffodils growing

wild in the

Woods and the bluebells, the

primroses, the gorse,

The vetch, the violets,

The daisy chain chaplets we wove for

you,

King of your dark eyes, your auburn

hair

And your apple red cheeks?

And the hawthorn blossom falling

speckled the grass

And you laughed.

And in the summer

When along the hedgerows the wild

roses and

The ivy tendrils wove white and dark

green

Canopies of shade

You became sun gold.

You took your first few faltering

steps

And laughed when you tumbled.

We dined then on strawberries, clotted

cream,

With never a care in the world.

April 14

A book, that is the thread Ariadne

gave to Theseus, the unappreciative Theseus, that he might

follow through all the passageways and corridors that were

the maze of her life and so understand her. A portrait, a

map, a journal. Different moods, different facets. All that

she might write, of what she might be. Uneven, textured,

varied, coloured. Sketches, a writer's notebook.

An environment of the past, Sussex and

England. Also Italy. The present tense of California. The

theme of alienation and exile.

She at the hub of a spider's web,

fraught in relationships to poles, daughter to father and

mother, sister and brother, wife to husband, mother and

sons.

The symbol of the sun clock, the

placement of action within a geographic area and in a social

era that determines and rules all unaware. And which is but

the backdrop, the chart upon which to plot the ship's

course.

April 15

Italian Interludes

I. Praiano

I listen, Though my ears are deaf. I

listen with my eyes and to the moiety of sound. I follow the

words, the looks. Beautiful strangers they are, of another

world. They sit at tables, consuming sacramental food. The

cleanliness of fish and fine sea wine. The conversation is

in diverse tongues and yet I follow, tasting the words like

kisses from lip to lip while the sense explodes like

fireworks upon the brain. I smile. And sip more wine.

The sea at our side slaps against the

rock. Waking this morning I had seen it rise up window with

Homeric hue. The wind-spewn, wine-dark water, puissant with

being, two prows against it whose shape belonged to Bayeux

art, to the paintings of Greek vases. I like it too well. I

speak of this, of the cleanliness of the sun, of the

simplicity of the food, the humanity of the people.

Today I sit with my father and his

friends, listening while they talk. Tomorrow, my husband

will come. I wonder how they will blend, how they will react

to one another. And I am a little afraid. Afraid of the

unknown. The world of tonight is one I know. Its language is

mine. I have been away so long but it is a homecoming. I

understand the mannerisms, the differing tongues, the

relationships. They are the script of a play I know by

heart. Everything is predetermined. But my husband will be

the unknown factor.

The fishing boats are leaving one by

one into the darkness, their lamps tied to each prow. They

diminish into the unknown horizon of night.

II. Siena

We lodge for the night in Siena at a

place my father knows. It is the home of an elderly lady.

She is aristocratic, impoverished and dying. The dolls of

her childhood are arrayed on the couch in the hall. They are

without life, infinitely old. Their faces are cracked and

their china eyeballs stare at us without comprehension;

their painted lips are laughing at some forgotten pleasantry

and their clothes are grey with dust.

We pass through the hall and the

dolls' heads do not turn to watch us go. We follow the

servant as she shows us to our rooms. She opens a door for

the signora and her child. I carry in my sleeping son and

lay him down on the bed from which the red damask cover has

been turned back. The damask is tattered and the lace-edged

linens do not have that whiteness I have become so used to

in Italy. But the room is palatial. The same red silk hangs

on the walls. The ceiling is frescoed with Venus' children.

At the louvred window swings a long mirror which catches and

flings back the shifting light of the street. A ewer and

basin stand on the marble wash stand. I find on the door the

tacked notice, required by the Italian government, stating

the price of the rooms and the class of the lodging, both

lowly.

Robin was asleep when I carried him

in. I changed him for the night and he awoke. Together we

lay and looked up at the painted ceiling. 'Bambino,

bambini', I exlain. 'Bimbo!' his soft voice replies. And

then he begins his nightly chant of words, of all the words

he knows, words like lalle,

(for latte,

milk), Mama, cane, cattivo. The

litany becomes softer, dwindles away and then he sleeps once

more. I undress quietly, leave the light burning and lie

down beside him. The children of the ceiling peer out from

behind the clouds and mock me.

I lie there, and with approaching

weariness dream Alice-in-Wonderland dreams, reliving the

day. Setting off in the tourist bus that morning from Monte

Mario with my father and his friend, listening forever to

the voice of the guide chanting of Etruscans, Tuscans,

watching the male and female cypress both pass and diminish

into Giotto landscapes. The cleanliness of Aquapendente

where we lunched in a trattoria of gleaming parquet and blue

and white tiled walls, more Dutch than Italian. And the

terror of San Gimignano, its tall towers and lightning

bolts, rain, sharp ozone, electric madness and hellish din.

And now Siena in the weariness of night, its streets washed

clean by rain.

A ceiling cupid laughs at me. Like

Robin he is eighteen months old, chubby, can toddle, laugh,

play but not yet speak. My child's most complicated

communication to date is 'Mama, da mi la!' Together we play

in the roman squares and parks with the wolf fountains and

stone lions. 'Guarda, leone!' Nearer and nearer goes the hand to

the lion's jaws. Nearer, nearer. Then

quick, snatch it away, growl, laughter. Robin plays with the

Italian children. A little girl at San Giovanni lets him use

her skipping rope. But he can't jump yet. He smiles while

she tries to teach him. His hair falls on his forehead, his

arms and legs are short and plump. I can't keep his shoes as

white as can the Roman matrons and I despair. Although his

shoes are not the whitest, I know him a princely child.

Another boy is aiming his bow at me.

There's no arrow in its taut string.

III. Sessa Aurunca

The Via Appia, tree-shrouded,

unravelled itself beneath the wheels of the bus. We

travelled swiftly, outrageously. The bullock carts, the

laden, paniered donkeys proceeded along the same plane but

in a dimension that differed from ours in speed, in era. One

held one's breath yet somehow it all worked, it harmonized

without violation. The bus lurched to pass, the passengers

would lean, sway, then resume their balance. The horn would

blast out its musical scale in mockery. Once in front and

now behind us would be the hay-laden cart, the clopping

horse, the peasant woman sitting atop the load with her

child. Sense emerged from impossibility. No collision, speed

maintained.

My father and his friends left their

seats and conferred with the driver. The bus came to a stop.

Surely we were yet far from the city of Naples, our

destination? We all got out and the bus drove off in a

triumphant swirl of dust and noise. There we stood, facing

the road in an orderly line. My father and his friend were

smiling. They had planned a surprise for me. The child I

held in my arms was half asleep with noonday drowsiness.

They turned and walked along the side of the road. They gave

no explanation and I asked for none, only waited to see what

would unfold. Though this was not Naples, but countryside.

We turned up a lane and a farm dog ran to us barking,

followed by Amalia in her blue dress patched and patched

again with light and dark blue slivers of cloth, her

friendly lined face framed by a yellow kerchief. Maria, her

daughter, came too. Then Antonio, the idiot son. And last

Vito.

Vito greeted us. So did they all in

their dialect. A chicken was caught and in the cavernous

darkness of the kitchen it was slaughtered. Amalia cut the

cock's throat with a dinner knife and let the blood flow

into the plate that Maria held. Robin watched all this

curiously. My eyes adjusted to the darkness of the room.

Food was kept in a kneading trough of wood. Dishes dried on

an upside down basket frame. Wheat was stored in burlap

sacks. Onions swung from the rafters. In the corner stood an

earthenware amphora full of cool water. Antonio and Vito

came in often to lift it and take a drink from its lip. A

fire was lit in the corner on the floor beneath the chimney

and the cock was fried. Zucchini squash was prepared also

and a salad of lettuce and olive oil. Maria took Robin with

her to her parents' bedroom. They went up an outside

staircase and Maria let Robin unlock the door with a huge

iron key. She brought down crude white plates, crystal

glasses, a loaf of bread, snowy napkins.

We ate at a rough-hewn table under a

shady vine. The chickens came and pecked our legs. The wine

we drank Vito had made himself. His grapevines swung from

fruit tree to fruit tree. His wheat was ripening and in its

midst were olive trees. Beneath the fruit trees grew squash,

onions, potatoes. Ancient eruptions of Versuvius made his

soil rich and fertile.

My father's friend and Vito talked in

dialect. They were cousins. From time to time Amato would

tell me things of the family in his broken English. They had

two hectares of good land, two daughters who were married,

two sons who had jobs elsewhere. Antonio was their eldest,

conceived out of wedlock and an idiot. But a good farmer. A

stupid, hard-working child. Antonio grinned at me, hearing

his name and knowing he was being spoken of, his blue eyes

laughed. He was stunted and smelly, but nice. He was

twenty-five years old and would inherit the farm. Maria, the

unmarried daughter, was fourteen. She held Robin on her lap

and made him eat. Her mother was, one by one, teaching her

the tasks of running a household. Last year Maria learned

how to launder clothes snowy white, this year to cook, next

year she could bake bread. Amalia was teaching her slowly,

completely, as she herself had been taught. Maria's formal

education was long ago dropped. But when we left she was

reading a Roman newspaper Amato had brought from cover to

cover.

The house, the farm was devoid of any

modern touch. It had remained an unspoiled piece of life

from the Golden Age. One concession alone was made to the

twentieth century, a radio from Germany that worked on

batteries and had good tone. Vito bought it to listen to

opera and to concerts. That day its battery was almost worn

down and the family listened with their ears to the set.

They had no money to buy a new one. Their crops they

bartered for seed and cloth. Coin was something they almost

never used.

After the meal Robin was taken up to

the large bedroom to sleep. He was too restless. Amalia told

me to lie with him. The bed was huge, far off the brick

floor. Faded banners hung on the rough wall above its head.

The board was inlaid with mother of pearl. A dark locked

press from which had come the plates and crystal stood in

the corner. The window had no glass but closed with wooden

shutters. The marble washstand had hanging from linen damask

towels with hand knotted fringes. They had come with

Amalia's dowry. We slept.

In the evening after coffee we left to

catch the bus to Naples. We flagged one down, standing in

the road, the Appian Way, and progressed on our journey.

April 18

A Song of Rye Sixpences

O Rye Town's a fair town

Of cobbled streets and Dolphin

Taverns.

Beyond lies Sussex, Kent,

All England stretching

Into Wales and over

Rippling sea to Ireland.

Marshes surround Rye Town

Where lambs can skip and ewes do

bleat.

Beyond are primrose woods and mossy

banks

And bluebell carpets magical.

Nightingales and cuckoos sing

Terue, terue, jug, jug, cuckoo,

And hawthorn blossoms on the hedge.

For England in April is Shakespeare

And England in May is Milton,

With a hey, nonny, nonny, ney,

Under the Greenwood tree,

Come hither, come hither, come

You with your princelike name,

There are sixpences and cobbled

streets

In Rye.

April 19

The two walked hand in hand in a world

of one. The women saw them from inside their shambled

cottages and cursed and went back to their work with

emptiness in their souls.

One old man sitting in the sun saw

them and slapped his knee and laughed. His daughter came out

to see what had happened. She saw the couple and spat on the

ground. The old man went on laughing, his face mahogany

coloured with the effort of it. His daughter slapped him

hard on the face. He stopped and smiled to himself an idiot

smile. His daughter went inside the cottage, wiping her

hands on her faded print apron.

The women remembered the night of the

storm and stared at the clothes they were darning, the dough

they were kneading, with emptiness. The rockets had flared

up and their men had gone out. Their husbands, their sons,

their lovers, had gone. The lifeboat had perished and day

after day the news would come and the women would be sent

for to identify the bodies washed up on the shore. Some of

the bodies they never did find. And they were alone in this

village of old men and children, of death and crying gulls.

Alone, where the waves of the sea slapped up against the

landwall and where the river Rother emptied itself in

rivulets and currents into the Channel, where the waves

danced and where the wind of the sea tempests howled.

May looked into Matt's face and

smiled. Matt pressed her thin hand. They walked slowly down

to the rotting dock and looked out to the sea where their

fathers had gone. Matt put his arm around May and pulled her

close to him.

The sailing yachts were coming down

the river. About six or seven of them were being towed

along. In the first one sat a fat woman, laughing at the man

above her who was towing the yacht. When they reached the

estuary the towers boarded the yachts and paddled them out

into the wind. The wind caught the sails and filled them.

The crews leaned this way and that, often right over the

water, with a wary eye on the cracking boom. The line of

sails floated away, skimming the water with the crying gulls

circling around them. The fat woman went on laughing at the

waves.

They watched the yachts, gazing at the

sea with its white crests of waves and the gulls balancing

on them. Matt kicked at some of the wood lying around. It

caved in like matchwood, and under them an eel slipped out,

disturbed, and swam away. May took a piece of stale, hard

bread out of her pocket and threw some crumbs of it on the

ground. The sea gulls came wheeling down on them. She held

some out in her hand and one perched on it and took it. She

laughed at Matt and he smiled back at her.

Then he took her hand and led her away

from the rotting boats and the rotting dock that had been

their fathers'.

She was slight in her thin print

dress. Her eyes were big and she looked scared when she

didn't smile. She put her head on his shoulder and Matt

looked down wonderingly.

They walked along the high river

embankment, lost in themselves. A small motor boat came

chugging softly down the river. The man at the wheel waved

to them cheerily. He chuckled to himself and went on.

They shied away from the town road to

Rye and wandered beside the marsh edge. May would stop and

pick marshcups and blue speedwell. She put them into Matt's

hands. He held them clumsily and dropped them along the road

as they walked together.

They went back over the Marshes in the

sunlight, wandering over the sheep runs that look so like

footpaths, crossing the little dike bridges that laced the

land with water. They were forever retracing their steps.

Matt had to wade over a dike that had no bridge. He carried

May in his arms and placed her on the bank. They smiled at

each other.

And May looked into his eyes that were

above her. The water in the dike gurgled along, drawn back

to the sea with the tides. The sheep nibbled the marsh

grass. May saw deep, deep into his eyes and knew fear. But

she smiled though she was afraid, though her heart was

beating in fear. She smiled and the corners of her mouth

trembled as she smiled, lying there on the grassy dike bank.

Matt looked down at her. He smiled,

too. He had held her as he walked through the water in his

fisherman's boots, had felt the water and mud squelching

around his feet. She was so close to him as she lay there.

The sheep bleated and the sea waves slapped against the dike

wall. The water gurgled, running through the many channels

that laced the land to the sea.

They were like sailors cast up on the

beach with a shipwreck and their ears were like two

seashells with the sounds of the waves murmuring and

clashing within them. May softly put her hand to Matt's hair

and smoothed it, with fear and wonder in her eyes. The water

in the channel went on its way down to the sea and back with

the movements of never-ending tides.

Then the mist came and they looked up

in fear. The Marshes were dangerous to cross even in

daylight. They ran blindly together, sometimes holding

hands, so they would not lose each other and sometimes Matt

carrying May.

They came home in the damp night with

the mist swirling around their face, May shivering in Matt's

coat over her thin shoulders, and their hair glistening with

particles of moisture.

The women in Matt's house stared at

him and the women in May's house were spiteful to her. But

her grandfather laughed over the fire and slapped his knee

in merriment as his idiot laughter filled the house and the

flames of the fire seemed to flare up in answer.

They walked together day after day.

May fed the seagulls and picked marshcups and Matt would

look at her. They walked in the Marshes often among the

sheep and the baaing lambs and the water of the land dikes.

In the distance would be the sound of the sea breaking

endlessly and the mewing of the gulls.

Then Matt went into the Service. He

came and stood before May in his khaki. She looked into his

eyes and did not tell him all she knew.

They sent him to the East, across the

ocean, and he didn't come back. May walked around the

cottage doing the chores with the women's spiteful eyes

watching her.

Her time came and she brought forth

the fruits of her body with labour. She brought forth a man

child to the village of death and the women forgot their

hatred and fondled the child with delight.

April 20

Life is a pilgrimage. But we wear the

cockle shells in our hats too timidly. We are afraid. We

dare not ponder on the destination. The old glory of faith

is gone. And we travel through alien territory alone in our

emptiness. Of, for the old courage and companionship! The

friendly sound of ambling palfries and the gay crowd that

told stories as they travelled, where are they gone? The old

yews under which they passed still stand on the Canterbury

roads. I walked under them in my childhood but the gay

tabards and the many-coloured cloaks were then only to be

worn by stage actors and clowns. People dressed in the

monotone of modern military camouflage, or civilian tweeds

and faded cottons. Companionship occurred with the uneasy

jest and the hollow laughter in the underground shelters

during air raids. We lived under the threat of death and

slavery, death or slavery.

April

21

Dear Ann Holland,

It is ten years since I have seen you.

You still live in Rye? To you it must seem an ordinary

place, full of the daily little things of life. You must

smile when I ask you to tell me about it, about the sunlight

on the old houses. You have always lived there and to you