JULIAN OF NORWICH

SHOWING OF LOVE,

PREFACE

TRANSLATED FROM THE BRITISH LIBRARY SLOANE 2499 MANUSCRIPT /S/

AND COLLATED WITH

THE WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL MANUSCRIPT /W/, THE

PARIS, BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, ANGLAIS 40 MANUSCRIPT,

/P/ AND THE BRITISH LIBRARY AMHERST

MANUSCRIPT /A/

I. On Julian of Norwich

ooks written by Julian of Norwich and by Margery

Kempe of Lynn, who knew each other, open windows into their

medieval world. It was a world which embraced East Anglia's

Norwich and Lynn, and, with Margery of Lynn, also Rome,

Gdansk, Bergen, Cologne, Compostela, Jerusalem and Bethlehem,

indeed all Christendom and beyond. A world in which women

could be writers of theology or at least recognized for their

holiness, such women as Hildegard of Bingen and Marguerite

Porete, Angela of Foligno and Catherine of Siena, Birgitta of

Sweden and Mary of Oignies. When the two East Anglian women

conversed with each other, Julian repeated to Margery that God

sits in our soul as a fair city. Sigmund Freud, in Civilization

and Its Discontent, gave as metaphor for the mind, the

city of Rome, as it once was, as it is now, as it will be, all

palimpsested, all layered, one upon the other. Then dismissed

the image as nonsense. But we shall find Julian's hermitage

within her city, though a paradox, to make profound sense, her

book to be of soul-healing. She makes of Norwich, Nazareth,

Bethlehem, Jerusalem, palimpsesting the Bible upon England.

Her city is every city, Mary its queen, Christ its king. Even

her text goes through version upon version which we show here

similarly palimpsested one with the other.

We learn, in Julian's text and elsewhere, of her anchorhold in the graveyard of St Julian's Church, nestled against the thatched roof of that church, the rain pouring down its eaves, and also of the herring, that would have been shipped up the River Wensum, at the bottom of her street of St Julian's Alley. For she compares the commonplace raindrops and herring of Norwich to the flowing out from God of Christ's redeeming blood. Today the area about her cell is bombed out, its church re-built. But once this was a bustling community of great learning and England's second largest city. We know she had women, named Alice and Sara, who lived with her and shopped for her, for they were left money in Wills. We can imagine them borrowing books for her from the Augustinians by the River, shopping for parchment for her in Parmenter Street. To one side, on its knoll, is Norwich Castle, to the other, beside river meadows, is the Cathedral of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, whose Benedictine monks had oversight over Carrow Priory with St Julian's Church and its Anchorhold. I've seen Adam Easton's schoolboy drawings in a Cambridge University Library manuscript of both Castle and Cathedral in Norwich and how to measure them by trignometry.

Julian's writings and their preservation reveal strong links with Benedictinism. She quotes from Gregory's Dialogues giving the miracle of St Benedict in prayer where the whole world becomes reduced to a single beam of light, it being explained that in the presence of the Creator all that is created 'seems full little'. Examining the manuscripts once possessed by the brilliant Norwich Benedictine, Adam Easton, who taught Hebrew at Oxford, who in 1381 became Cardinal of England, his titular church being Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, and who knew John Whiterig and Thomas Brinton in England, and William Flete, Alfonso of Jaén, Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena in Italy, one finds that Julian's writings reflect those of Adam Easton himself and likewise of the books in his library, for she, too, knew Hebrew and the Victorine edition of the mystical writings of Pseudo-Dionysius, John Whiterig's Meditationes, William Flete's Remedies against Sin, the Dialogo of Catherine of Siena and the Revelationes of Birgitta of Sweden, edited by Alfonso of Jaén. In one of Adam Easton's manuscripts, on Canon Law, he makes notes about a deformed, crippled woman. She writes about her great pain, both physical and mental, and of her 'wanting of will' (a true definition of depression), her desire to die when young. Adam Easton and Julian of Norwich together write on the Hebrew meanings of the name 'Adam', as meaning 'Everyman', 'Everywoman', and 'clay' and 'red'. In the Life of Christina of Markyate we learn that Benedictines initiated conversation with the one saying 'Benedicite,' the other replying 'Dominus'. Julian several times says this in her text, 'Benedicite, Dominus'. The title Margery gives to her, 'Dame Julian', is that of a Benedictine nun. Her manuscripts were to be secretly preserved from persecution in Brigittine and Benedictine convents in England and in exile, both Orders associated with Adam Easton.

A brilliant crippled woman in medieval Norwich could have been useful to Benedictine Carrow Priory, which supported itself with boarding young girls and educating them, some among them named 'Julian', several of these in turn becoming their nuns. Julian's autobiographical writings speak of her 'service in youth' to God, and also of considerable illnesses, these being so burdensome that she desires to die early, stressing this in all three versions of her Showing of Love. Her desire was partly granted, a devastating illness afflicting her on 8 or 13 May 1373 (one manuscript has 'viii', the other 'xiii'), when she was just past thirty, and under her family's roof. But she lives to tell its tale, twice over, at fifty, in 1393, and at seventy, in 1413. Her autobiography becomes like Tolstoy's 'Death of Ivan Ilych', like Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy, like Augustine's Confessions, like the Books of Job and of Jonah. But it also swirls about medieval Norwich. In her dessicating, hallucinating fever, immediately after the 'religious person' (which means a Benedictine monk), has visited her, she has a horrific vision of the fiend, who comes with hair like red unscored rust, his skin freckled with black spots, like burnt tile stones, clutching her by the throat, while she still believes in God. A similar tale was told in Norwich, recorded in a Lambeth Palace Syon Abbey manuscript, of such a vision in 1350 to a man who had earlier seen written in a book of the need to pray to the Virgin, and who then does so when being throttled by the devil. Who therefore has to release him. Julian's vision recalls another, had by St Birgitta, concerning evil Cardinals as like freckled, burnt tile stones and rust, Birgitta being told they may not preside at the altar, while they are in sin. Pope John Paul II, for whom 13 May is also significant, specifically cited this vision by Birgitta when proclaiming her Patron, Co-Patroness, of Europe.

It is likely that Julian, unable for health and social reasons to become fully a choir nun at Carrow, earned her keep teaching, both before and after her illness, until Archbishop Chancellor Arundel's 1407-1409 Constitutions would forbid her doing so. Her writings throughout centre most of all in the themes of learning and teaching, and twice she mentions theology as like an ABC. The medieval tradition has St Anne teach the Virgin to read, then St Mary teach Jesus his letters, his prayers. Women, especially Anchoresses, taught boys in Dame schools their ABC and their beginning Latin, from which foundation men could then enter the Church as monks and as priests, even becoming scholars, bishops, cardinals, popes. It is also possible that Julian once journeyed as a pilgrim to Rome and saw there the Veronica Veil, the Vernicle, which she describes so movingly in her vision of Christ. This relic, kept in St Peter's and written about also by Dante and Petrarch, is now lost, the Holy Year of 2000 substituting for it the Holy Shroud of Turin. Had she visited Rome she would likely, from her Benedictine associations, have stayed with the Benedictine nuns at St Cecilia in Trastevere, for this was Adam Easton's titular church in Rome as Cardinal and where his retinue, including many from Norwich, lodged, conveniently across the Tiber (Tras-tevere) close to the Vatican.

The 'religious person', which means 'Benedictine

monk', who laughed at her bedside, then became serious about

her vision in 1373, and who is mentioned in the Paris, Sloane

and Amherst Manuscripts, could have been Adam Easton. He could

also have been 'the man of holy Church', by 1381 England's

Cardinal of St Cecilia in Trastevere, who told her of St

Cecilia and of the martyr's three wounds with a sword,

mentioned in the 1413 Amherst Manuscript. Adam Easton was

likely in England at the date of Julian's vision in May, 1373,

and were she his sister and thought to be dying, having been

sent away, a failure, from Carrow Priory, he could have

visited her under their mother's roof. His brilliant career at

Oxford, interrupted with several years of preaching very

effectively in Norwich against the Mendicants, had next taken

him to the Papal Curia in Avignon and Rome. He had been made

Cardinal in 1381 in exchange for his finely written book on

the power of the Pope, Defensorium ecclesiastice

potestatis, in which he displays his Hebrew and

Pseudo-Dionysian learning. In 1382 he arranged the Coronation

of King Richard II and Queen Anne of Bohemia, daughter of the

Emperor Charles, in Westminster Abbey, for which he helped

write the Liber Regalis.

A brilliant record, save for his rather underhand plotting against John Wyclif with the Pope. Meanwhile, Pope Urban VI was struggling to reform the Cardinals, who rebelled against him.

Then the Pope, in 1385, in a rage, threw six Cardinals in a dungeon and had them tortured. One of these was Adam Easton. The English Benedictine Congregation, Parliament, Oxford University and King Richard II all wrote impassioned letters pleading that Adam's life be spared and his benefices restored, comparing him to the wounded traveller in the Parable of the Good Samaritan, and begging that the Pope bind up his wounds with wine and oil. The other five Cardinals all met their deaths, Easton being the only one left alive to tell the tale. Adam Easton remained a prisoner from 1385 until Boniface IX restored him in 1389, at which point he returned home to Norwich to carry out his vow made to St Birgitta (who had died 21 July 1373 in Rome on her return from Jerusalem), in his dungeon that he would work for her canonization if she would spare his life. Recall St Birgitta's grim prohecy about corrupt Cardinals. I believe Cardinal Adam Easton then edited Julian's Long Text, inscribing its table of contents, its admiring chapter divisions, and its colophon, having been in Norwich with Birgitta's Revelationes and other books shipped from the Lowlands during the writing of the Long Text Showing of Love, while he himself was composing the canonization document validating Birgitta of Sweden's writing of similar visions to Europe. He then died in Rome in 1397 and is buried in St Cecilia in Trastevere, both the body of the Roman martyr saint and of the Norwich cardinal being later found incorrupt, perfectly preserved. Julian would have lost, at his death, her powerful patron.

Adam Easton and John Wyclif, both of Oxford University, had became deeply opposed to each other, Easton waging an intense campaign against Wyclif. Wyclif desired that the Church return to the Gospel, that it use the vernacular in the liturgy so that common men and women could understand the Bible, and that it cease from seeking wealth and power, its university-trained priests instead living learned simple lives amidst their parishes, caring for and educating their flock. Easton, on the other hand, from his readings of Pseudo-Dionysius, and from his Benedictine heritage, supported the hierarchy of the Pope and the Church and the right of Benedictine monasteries to own rich possessions. He instigated the persecution of the Wycliffites, also known as 'Lollards', having earlier preached against the Mendicant Orders present in Norwich. Several bishops became anti-Wycliffite, including Bishop Le Despenser of Norwich, and Bishop Thomas Brinton of Rochester, Easton's fellow monk at Norwich and fellow student at Oxford, and, following these men, the powerful Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor of England, Thomas Arundel, who cracked down on Wycliffite Lollards, for political reasons, as both heretics and traitors, by forbidding lay people the Bible or the liturgy or theological writings in English, and being particularly draconian against learning in women, 1407-1409. Already, the first Lollard to be burnt in chains at the stake at Smithfield, as both heretic and traitor, in 1401, was William Sawtre, Margery Kempe's curate at St Margaret's in Lynn, who had been hounded by both Despenser of Norwich and Arundel of Canterbury for saying he worshipped Christ more than the cross of wood upon which he was hung.

It was at this period that Julian would have lost her support system of teaching young boys their ABC, their Catechism, their Bible, their Latin. And that loss of support is reflected in the flurry of Wills in 1394, 1404, 1415, and 1416, leaving money for her survival as Anchoress of St Julian's Church in Norwich. The final Will leaving funds for Julian was written by the Countess of Suffolk, Isabella Ufford, and had as its executor, Sir Miles Stapleton, whose daughter, Lady Emma Stapleton, in turn became the Anchoress to the Carmelites in Norwich and for whom it is possible that the Amherst Manuscript was first assembled. Julian would also have had to dramatically revise her life work, the Showing of Love. Every page had translated passages from the Bible into English, and this was now strictly forbidden, upon pain of burning at the stake as a Lollard. The great sadness is that Adam Easton had translated the Bible from Hebrew into Latin, correcting Jerome's errors; then his Bible was stolen from him. He had criticized Wyclif for being unscholarly and for translating Jerome's Latin errors into English, rather than going directly to the Hebrew. Julian miraculously is translating from the Hebrew, not into Latin, but into English, centuries before the King James Bible. Her 'All shall be well' translates the Hebrew 'Shalom'. The Vulgate and the Wyclif Bibles give this merely as 'recte' and 'right'. She and the King James Bible's translators get it right.

Perhaps we do not know her real name, for she may have taken the name of the male saint of St Julian's Church. There is a manuscript speaking of the similar visions of one Mary Westwick, spelling this name 'Oestwyck', while Adam Easton spelled his 'Oeston', the Westwick area near the Castle having been Norwich's Jewry from 1144-1290, before their expulsion by King John. This Jewry had funded the building of Norwich Cathedral. A remnant, perhaps as converts married into Christian Norwich families, could have survived. Julian and Adam may have shared the heritage of the Carmelites Teresa of Avila and Edith Stein.

II. On Her Showing of Love

![]() he

manuscripts of the Showing of Love have internal

indications as to the dates when she wrote their original

versions. The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript /W/, copied out

later, but having the date '1368' on the first folio, could

indeed have originally been written then, before the 1373

vision, since it presents her theology, speaking of her desire

to die young, and God agreeing. She would then have been 25.

Other contemplative women have been similarly prococious. One

thinks of Catherine of Siena and Thérèse of Lisieux. It

contains in its abbreviated form Julian's essential theology,

Mary contemplating her yet unborn Child with the 'O Sapientia'

Advent Antiphon, the hazel nut in the palm of her hand, Jesus

as our Mother, her desire to die young, her wanting a vision

of the Crucifix. 1368 is the year of Birgitta's vision of the

Crucifix which spoke to her in the Lateran. The Westminster

Manuscript significantly lacks the death-bed visions and the

Parable Showing of the Lord and the Servant.

he

manuscripts of the Showing of Love have internal

indications as to the dates when she wrote their original

versions. The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript /W/, copied out

later, but having the date '1368' on the first folio, could

indeed have originally been written then, before the 1373

vision, since it presents her theology, speaking of her desire

to die young, and God agreeing. She would then have been 25.

Other contemplative women have been similarly prococious. One

thinks of Catherine of Siena and Thérèse of Lisieux. It

contains in its abbreviated form Julian's essential theology,

Mary contemplating her yet unborn Child with the 'O Sapientia'

Advent Antiphon, the hazel nut in the palm of her hand, Jesus

as our Mother, her desire to die young, her wanting a vision

of the Crucifix. 1368 is the year of Birgitta's vision of the

Crucifix which spoke to her in the Lateran. The Westminster

Manuscript significantly lacks the death-bed visions and the

Parable Showing of the Lord and the Servant.

The Sloane /S/ and Paris /P/ Manuscripts contain the Long Text of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love. Within this form of the text, she explains that her death-bed vision took place in May of 1373, and that she then contemplated upon it for from fifteen /S/ (1388) to twenty years /P/ (1393), performing this Book of her Showing of Love, finishing its final version when she was fifty. These Manuscripts contain all of the Westminster version of her text, boiler-plating on to its theology the series of visions as narrative frame that she had when she and those with her thought she was dying. She was inclined to doubt the validity of these visions, but mentioned to 'a religious person' that she had seen the Crucifix 'bleed fast'. He, who had been laughing, possibly the Norwich Benedictine, Adam Easton, immediately took her seriously, about which she was in anguish.

Julian thus begins writing the Long Text while Adam Easton is still a prisoner of his Pope. She completes it when Cardinal Adam Easton is finally able to return to Norwich, bringing books with him, and where he settles down to write his Defence of Birgitta of Sweden, the Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae, 1389-1391. In his dungeon, while under torture, he had prayed to Birgitta of Sweden that if his life were spared he would effect her canonization. Birgitta had spent a lifetime, from forty to seventy, writing a massive tome in many books, about her visions, some of which she had had as a child in Sweden, had travelled to Italy, lived in Rome, then pilgrimaged to Jerusalem and Bethlehem in the last year of her life. Her Revelationes had first been brought to England and likely Norwich, in 1348, where Adam Easton as a young monk of eighteen could have first seen it, when she sought to end the Hundred Years War between the Kings of France and England. Adam Easton now returned to Norwich, 1389, with a fine copy of Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes from which he culled the argument for her Canonization, collating this with that already written by Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Jaén which is filled with cross-references, like those in Julian's Showing, and where the chapters have similar headings as do those in the Sloane Manuscripts of Julian's Showing.

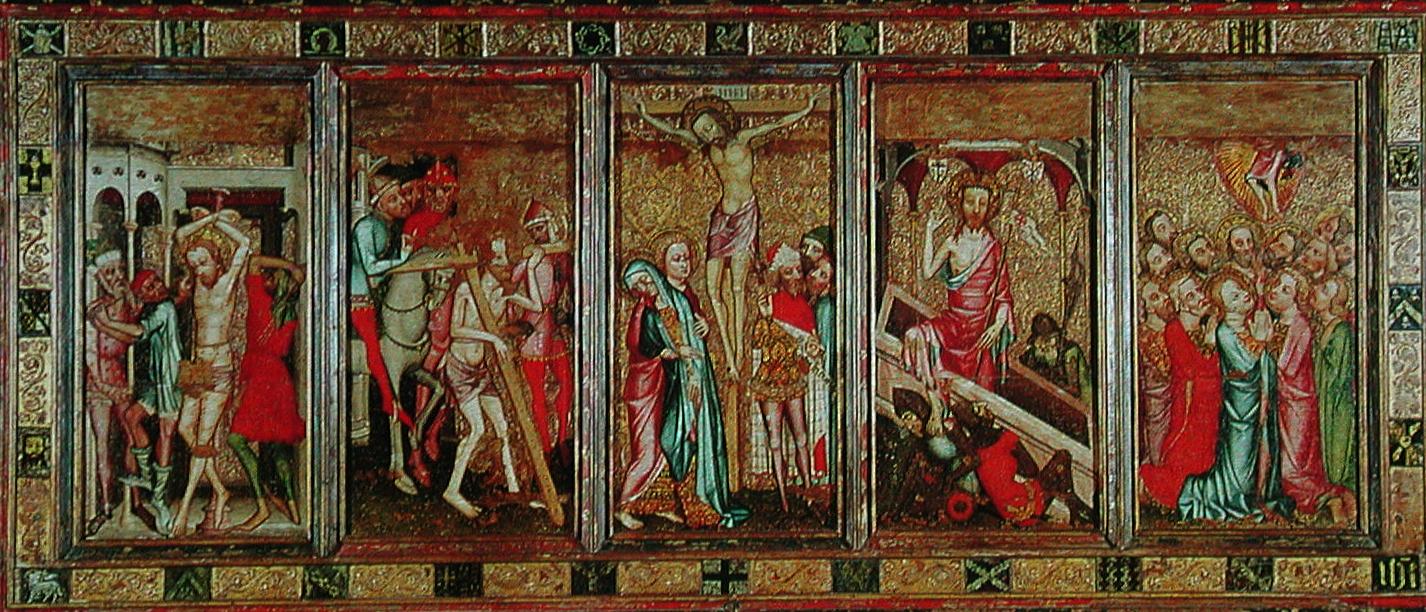

These chapter headings in the Showing of Love are not written by Julian but by her editor who admires her. He may well be Adam Easton who is attempting to have her write a similar book as had Birgitta of Sweden. There are direct echoes of the Revelationes in the Showing, but more of these are to be found in the Sloane chapter headings than in the Sloane and Paris text. Moreover, Julian constructs the Parable of the Lord and the Servant in such a way that it evokes the Coronation pageantry of the Liber Regalis, and the punishing of Adam Easton with the dungeon imprisonment and torture by his Pope. Adam Easton's own Defensorium Ecclesiastice Potestatis had emphasized the mirroring between earth and heaven, between kings, emperors, bishops and popes, and God. Julian seems cognizant of all these works and likewise of the letters sent pleading for the life of Adam Easton and the restoration of his benefices citing the Parable of the Good Samaritan. Nor was the treatment of Adam Easton the only atrocity of which Julian would have known. She likely witnessed the drawing along the cobbled streets of flint of Norwich of malfactors, before their being hung and quartered. She describes in her hallucinatory Crucifix vision the effects of such drawing and hanging as palimpsested upon the face and body of Christ. John Litester, the 'King of the Commons', during the Peasants' Revolt was so executed by Julian's Bishop of Norwich, Le Despenser, who commemorated it with a gift to the Cathedral of the Despenser Retable, showing Christ's Crucifixion.

(Recall Gay's Beggar's Opera making a similar analogy between the Tyburn execution and Christ.) In part, Julian's text is therapy for trauma syndrome. Like Viktor Frankl, Holocaust survivor, she is a doctor for troubled souls. Having healed her own soul through writing her own book, her Showing of Love can and does heal others.

Her Book of the Showing of Love, with its Parable of the Lord and the Servant, reflecting his own trauma and restoration, was one in which Adam Easton could take pride. But in 1413 everything had changed. Cardinal Adam Easton had died and been buried in the Basilica of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere in Rome in 1397. Archbishop Chancellor Arundel, for political, more than for religious, reasons, was forbidding upon pain of death so much of what was contained in the earlier Showing of Love, the Bible and theology in the vernacular, teaching by a woman, the concentrating on Christ rather than upon sculpted wooden painted crosses. Piers Plowman during this period had to be revised in a censored and shorter version to survive at all. Julian at seventy, with the help of a Carmelite scribe, similarly revises her Showing of Love and it appears in abbreviated form in a manuscript forming a gathering of contemplative texts for such a person as Lady Emma Stapleton, Anchoress to the Carmelites of Norwich. The Amherst Manuscript /A/ also contains Marguerite Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls, Jan van Ruusbroec's Sparkling Stone, as well as fragments from Henry Suso's Horologium Sapientiae and from Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes, all of these writers associated with the 'Friends of God' circle, as if this manuscript were representing Julian's own contemplative library. This version lacks 'Jesus as Mother', the Parable of the Lord and the Servant, and much of the material translating the Bible. Yet it crystallizes Julian's mature thought and exemplifies her courage. For using the Lollard term, her 'even-Christians', Julian courts burning by Arundel. She ends this text so, bravely adding 'Amen', knowing its Hebrew meaning as being that which is said, which is spoken, which is done, which is created. We, as the Royal Priesthood, say and live this word when we receive the Host.

III. On Her Theology

ulian as a lay woman could only have received that

Host fifteen times a year, but would daily, as an Anchoress,

have witnessed and worshiped it through her window that looked

onto the altar at St Julian's Church. She shapes her text upon

the Word as far as a woman can, remembering that Mary was

present at the birth and at the death of Jesus, and that she

thought upon all these things in her heart, having 'mind' of

his death, his birth. Daily, Julian would have contemplated

the Bible, its Hebrew Scriptures, its Gospel, Acts and

Epistles. Then, in lectio divina, with her Book, she

mirrors herself and ourselves into that mirroring, that

'compassion' with the Incarnation and the Passion.

George Eliot in Middlemarch wrote

'How will you know the pitch of that great bellJulian's visionary parable of the Lord and the servant is the parable of the entire Bible, from Adam to Christ, and of the Incarnation and Resurrection. Her text centres on the Incarnation, beginning with the Annunciation to Mary, her pregnancy with Christ, her contemplation, in lectio divina, of her coming Child, as mirroring Julian's conception, then birth, of her Book of the Showing of Love. That image she takes from Marguerite Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls. Many current studies of Julian of Norwich dive deep into obscure waters of 'soteriology'. Julian, instead, knew how to use simple words to present profound concepts clearly, to be like George Eliot's silver flute in harmony with the great bell. She knew her Bible, including its Isaiah on the Suffering Servant, inside out and sideways. Julian of Norwich and Birgitta of Sweden both had access to scholars of Hebrew, likewise Elizabeth Barrett Browning and George Eliot brought their brilliance to women's books, casting them in the mould of theology, writing them for all. Julian, as we have said, probably taught small children their alphabet and their catechism. A manuscript survives in Norwich Castle which is not the Showing of Love, but a translation into Middle English of the Letter Jerome (actually Pelagius) wrote to 'The Maid Demetriade who had vowed virginity' and catechetical works which may have been written by her for its hand matches the corrections to the Amherst 1413 Manuscript. (Indeed, Julian is included in The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 313.) This Norwich Castle Manuscript includes a fine discussion of the Hebrew meanings of 'Amen'. Julian likely also knew some of the most brilliant men in England and certainly receives the admiration of one of them who is editing her text with comments to each chapter. She is simple and she is profound. And she is the more profound for presenting this Magnificat, balancing Christ's Beatitudes, as a woman, thus sharing Mary's gender and joy and desolation and glory.

Too large for you to stir? Let but a flute

Play 'neath the fine-mixed metal: listen close

Till the right note flows forth, a silvery rill:

Then shall the huge bell tremble - then the mass

With myriad waves concurrent shall respond

In low soft unison'.

She speaks of Christ our brother and of 'Master Jesus'. (Adam Easton's Oxford career was interrupted with his return to Norwich several times to preach, on the order of his Prior, so he never completed his doctorate in theology, remaining always 'Master Adam', unlike his fellow student, Thomas Brinton. They only relinquished these titles to be Cardinal and Bishop.) Julian combines Adam and Christ. She then blends Mary and Christ, having Christ be our mother into whom we are all born, reflecting the Gospel of John's discourse of Christ with Nicodemus. (Her first editor into print, Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., went even further and called her 'Mother Julian'.) Yet her language is pre-Women's Liberation, insisting that masculine forms, as they do in Latin and other Mediterranean languages, include the feminine. For example:

For in our Mother Christ we profit and increase, and in mercy he reforms and restores us, and by the virtue of his Passion and his death and Uprising, ones us to our substance. Thus works our Mother in mercy to all his children who are pliant and obedient.She explains this by saying 'Adam' means not just the single Adam, but all men and all women, as is true of its Hebrew meaning. And that where she says 'we', she means again all men and women. And that Christ Jesus is Holy Mother Church. St Joan of Arc would say the same to Norwich's Bishop at her trial. In Julian's day, one could only be Christian in Christendom, Jews having been banished from England on pain of death, so to describe her relation with 'mankind', she speaks of our 'even-Christian', that we are all one, all his brothers, his sisters, his mothers, as Christ said of us. In Christ's Parable of the Good Samaritan one's 'even-Christian' is all humanity.

In the Parable of the Lord and the Servant Julian

sees God as seated on the ground and dressed in blue. That was

the iconography of the Virgin in her Humility, begun at

Avignon by Simone Martini for the Cardinal Stefaneschi,

showing the Virgin as seated on the earth, in a Wilderness,

and dressed in blue, showing the Cardinal himself in his

scarlet robes as kneeling before her, present within the scene

as donor. That iconography is echoed in the Wilton Diptych

showing Richard II, Julian's king, kneeling as donor, in a

Wilderness, with his patron saints, before the blue-clad

Virgin and Child who are surrounded by angels.

For Julian and for Adam this blueness also reflects the Letter, Epistola LXXVII, Jerome wrote to Fabiola at her request explaining to her the garb of the High Priest Aaron, Exodus 28.31, stressing his hyacinthine blue robes, a document Adam used in his Defensorium Ecclesiastice Potestatis. Mary and Christ our High Priest palimpsest one upon the other, in compassion of the Passion. And so do we join them, 'oneing' ourselves into this mystery. Julian likewise centres on the Trinity, noting that wherever she speaks of one Person, all three are signified and contained. Norwich's Cathedral is dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. Adam Easton as Benedictine in the Cathedral Priory of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Norwich would have preached often throughout Norwich on this topic.

In her day the Church taught that Jews were damned unless converts. Julian bravely says she cannot see this in her vision. Perhaps Julian's own family had roots in Norwich's Jewry. Certainly her text uses parts of the Jewish Shema, 'Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord, And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might'), over and over again, going on to teach this to us as the Shema itself bids us do. Another prayer, the first a Jewish child, like Jesus, would be taught is 'Into your hands I commend my spirit'. Mary, who taught it to him when he was a child, then heard him repeat her words as she stood beneath him while he was dying on the Cross. Julian fills her text with images of God's hands, which becomes her own holding the hazel nut which is all God's Creation. In Hebrew the letter yod, i, also means hand and ten and is the smallest letter of the Hebrew alphabet and begins God's name, and Julian's.

The sweet gracious hands of our Mother be ready and diligent about us. For he in all this working uses the office of a natural nurse and has nought else to do but to attend to the salvation of her Child.Her Showing of Love shows awareness of the original Hebrew of the Bible in several places, not least the 'All shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well' which translates 'shalom' better than does the Jerome Bible's 'recte' and the Wyclif Bible's 'right'. The Hebrew word for peace, Maria Boulding tells us, means far more than a truce amidst war, which is the sense of the Greek 'irene', the fleeting rainbow amidst storms, 'shalom' being instead a totalizing of wellness, goodness, oneness, Creation and Creator in harmony, universal peace.

One of the extant manuscripts which Adam Easton once owned is Rabbi David Kimhi's Sepher Miklol. Kimhi wrote 'Jerome your translator erred in corrupting the text, "The Lord said to my Lord, Sit at my right hand", of Psalm 110.1. Adam Easton explained that the phrase does not mean 'right hand' literally, but as 'honoured'. Likewise does the Cloud of Unknowing author say this. And Julian's text concurs. Earlier, Marguerite Porete had been burned at the stake in Paris, 1 June 1310 for proclaiming in The Mirror of Simple Souls sentences similar to those Julian would write. Later, Elizabeth Barton, who read books of Birgitta of Sweden and Catherine of Siena and, perhaps, Julian of Norwich, at Syon Abbey, and was made to write a great Book of Revelations modelled on theirs, when questioned whether the Son sat at the 'right hand' of God the Father, replied, 'Nay it was not so, but One was before Any Other and One in Neither'. For which she was drawn, hanged and beheaded in London, 20 April 1534.

A young Russian woman scholar, translating Julian into Cyrillic, queried why Julian speaks of our time and God's time becoming one time. I sent an e-mail back to Moscow, explaining that in the Middle Ages time is seen like a clock face, we, on the outside, just having a part of it, God, at the centre, being all time, no past, no future, for all these are present at one and the same time. When we attain the centre we are in that 'oneness' of time with God, which is eternity. This is stated in Augustine's Confessions XI and in Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy. In Judaism time is linear; in Hellenism it was believed the world was eternal and always would exist, not being created in time, not ending in Apocalypse. Christianity blended the two time systems into this image of the circle and the centre. Julian sees God in a point. Sometimes I think Julian's great secret that God will do at the end of time will be to have time go backward, back to Adam, before the Fall, thus saving God's Word in all things, undoing all sin, as he tells her he will do. Julian also uses again and again the expression of God's knowing as 'without beginning', as from 'before any time', as knowing what shall be from before beginning, being there with grace and mercy in our prayer before we pray. Both she and Adam Easton speak of 'presciencia' and of the need not to lose time, God's gift to us, the Cloud author saying God gives us one time, not two, and that we must use it well. While Julian, the Pearl Poet and the Gospel Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard also explain that one day's prayer, or prayer in one's youth, may be enough to save one's soul.

Julian uses the word 'kind' to mean nature, what is natural. And, as is true in medieval theology, Nature is of God, while sin is to act against nature. To be cruel and selfish and competitive, to be 'red in tooth and claw', is to be against nature, unnatural. Somewhere, between Julian's fourteenth century and our twenty-first, nature has conceptually been barbarized, mechanized and violated. Indeed, Julian's text looks back to far earlier texts, from the dawn of time, of history, from Babylon, from Egypt, from Rome, from before Christianity, which all speak of the need to defend the weak against the strong, to be 'kind', natural, nurturing, to others, rather than to one's self, as the mark of civilization, of humankind, of the survival of the whole. Julian speaks of man and woman created in God's nurturing image. In this Julian's most obvious model is Hildegard of Bingen, whose final text, in a finely illuminated manuscript preserved in Lucca, the Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis, speaks of the need for Mankind to reverence Nature as of God, not violating her, for health and wholeness, for the shalom of the Creation. Julian's more modern and far more despairing counterpart is Mary Shelley who wrote Frankenstein, which is the Showing of Love reversed and turned inside out, man de-natured, de-humanized, mechanized, a world of lonely abusive cruelty.

IV. On The Book of Margery Kempe and The Book of the Showing of Love, the Oral Text

When the learned humble Julian was old and in her Norwich anchorhold, around 1413-1415, at the time the Amherst Manuscript Showing of Love said it was being written, she was visited by another would-be anchoress, this one illiterate, traumatized, having books read to her, such as about Marie de Oignies and by Birgitta of Sweden, who had both been married. Margery was the mother of many children, only one of whom seemed to have survived, and whose son and daughter-in-law, for her therapy, had her dictate her Book of Margery Kempe. Reading Margery's Book is like having a tape recorder in medieval Norwich, brought from medieval Lynn, and then replayed in Lynn, years later. For this reason, in this section, we present the original surviving texts diplomatically, rather than translating them, to give the readers of this translation as closely as possible the sense of Julian's spoken voice, of her dialect. (The references are to the manuscripts' foliation as given in the definitive edition by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway, of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love, SISMEL, Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2001.)

Margery in The Book of Margery Kempe has her scribes explain to us (M, folio 21)

Margery and Julian's conversation continues

Julian cites Saints Paul and Jerome to Margery:

In this passage has Julian intended not 'city' but 'seat', or has Margery misheard the word? But perhaps Julian deliberately plays upon the likeness of the two words. She may be using the concept expressed throughout Luke 14 where guests need to exercise humility to enter the Kingdom of God, a kingdom that is within us.

Apart from the Hilton and Julian texts in the Westminster Manuscript making this same point are other texts associated with Julian. Among them, Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 78v:

. . . iusti sedes est sapiencie. ffor as seith holy write the soule of the ry3tful man or womman is the see & dwelling of endeles wisdom that is goddis sone swete ihe If we been besy & doon our deuer to fulfille the wil of god & his pleasaunce thanne loue we hym wit al our my3te.Likewise, John Whiterig, fellow student with Adam Easton at Oxford, then Hermit on Farne Island, who deeply influenced Julian's text, uses this passage,'Anima iusti sedes est sapiencie', in Contemplating the Crucifixion, deriving it from Proverbs 10.25b (Gregory, Hom. XXXVIII in Evang. PL 76, 1282).

Julian's theology presents this marvelously wise image of the city in the soul, Christ its King. Margery's text had emphasized the City of Norwich with its inspired and inspiring anchoress:

& than sche was bodyn be owyr lord. for to gon to anIn Julian's day Norwich was the second largest city in England, its cathedral being rebuilt during her lifetime in Gothic style. We see it imaged as Constantinople in the Luttrell Psalter. Spiritually, it was inspiring magnificent church art and architecture - and Julian's Showing. Let us leap forward to George Eliot writing on Coventry and the Reform Act in her Middlemarch, reflecting back to Plato and his Republic:

ankres in the same Cyte which hyte Dame Jelyan'.

1st. Gent. An ancient land in ancient oraclesInterestingly, this phrasing concerning the soul as a city is closer to that of the Sixteenth Showing in the 1393/1580 Paris Manuscript (P143v-145v) and the 1413/1450s Amherst Manuscript (A112), which both give vestiges of the Lord and the Servant Parable, than it is to the earlier version, the Fourteenth Showing, present in the Westminster and Paris(P116-119) Manuscripts (W101-102v; P116-119).

Is call 'law-thirsty:' all the struggle there

Was after order and a perfect rule.

Pray, where lie such lands now?

2nd Gent. Why, where they lay of old - in human souls.

liance therwith: It behouyth

to seke into oure lord god

in

whom it is enclosyd. And an=

nentis oure substance it may

ryghtfully be called our

soule.

and anentis our sensualite

it

may ryghtfull be called our

soule. and that is by the

onyng

that it hath in god. That

wur=

shypfull cite that our lord

ihesu

syttith in. it is our

sensualite.

in whiche he is enclosed.

and

our kyndely substance is

beclo=

syd in ihesu criste. with

the blessed

soule of criste syttyng in

reste

in the godhed. And I sawe

ful

surely that it behouyth

nedis

that we shall be in longynge

and in penance. into the

tyme

that we be led so depe in to god

that we may verely &

truely

know oure owne soule. And

sothly I saw that in to thys

high depenes oure lorde hym

selfe ledith vs in the same

loue

that he made vs. and in the

same

loue that he bought vs. bi

his

mercy & grace through

vertue

of his blessed passion. And

not withstondyng all this we

may neuer comme to the full

knowyng of god. tyll we

first

know clerely oure owne

soule.

ffor into the tyme that it

be in the

ffull myghtis we may not be

all full holy. and that is

that oure

sensualite. by the vertue of

cristis

passion be brought up into

the

substance with all the

profitis of

oure tribulacion that oure

lorde

shall make vs to gete by

mercy

& grace.

Julian continues:

IV. On The Showing's Manuscripts

![]() idespread

destruction of Julian's manuscripts of the Showing of Love

would have occurred first under this persecution of the

Lollards, which had brutally executed Margery's curate,

William Sawtre, and had almost swept up Margery herself into a

heretics' pyre. Then even more such manuscripts and printed

books would have been destroyed under the persecution of the

Catholics. Because of the Reformation, all but one, the

Amherst Manuscript /A/, of Julian's surviving manuscripts of the Showing

of Love came to be outside of England. Today only one

remains abroad, the Paris Manuscript /P/. There may

still be unfound Julian manuscripts in Flemish or Dutch

libraries, which were the exemplars to Sloane and to Paris. It

would be splendid if these could be discovered. That all these

Julian of Norwich Showing of Love manuscripts have

Brigittine or Benedictine connections argues for the patronage

of her work by the Norwich Benedictine Adam Easton, the

Cardinal who effected Birgitta of Sweden's canonization in

1391, following Birgitta's death in June, 1373.

idespread

destruction of Julian's manuscripts of the Showing of Love

would have occurred first under this persecution of the

Lollards, which had brutally executed Margery's curate,

William Sawtre, and had almost swept up Margery herself into a

heretics' pyre. Then even more such manuscripts and printed

books would have been destroyed under the persecution of the

Catholics. Because of the Reformation, all but one, the

Amherst Manuscript /A/, of Julian's surviving manuscripts of the Showing

of Love came to be outside of England. Today only one

remains abroad, the Paris Manuscript /P/. There may

still be unfound Julian manuscripts in Flemish or Dutch

libraries, which were the exemplars to Sloane and to Paris. It

would be splendid if these could be discovered. That all these

Julian of Norwich Showing of Love manuscripts have

Brigittine or Benedictine connections argues for the patronage

of her work by the Norwich Benedictine Adam Easton, the

Cardinal who effected Birgitta of Sweden's canonization in

1391, following Birgitta's death in June, 1373.

The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript /W/

The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript was, according to its dialect and script, written out at the Brigittine Syon Abbey by a Brigittine nun there, around 1450. She had access to other manuscripts of the Showing of Love and likewise did other readers of the text for it is carefully corrected against them. The manuscript begins with works from Walter Hilton, two Psalm commentaries, and excerpts from The Ladder of Perfection, a work he originally wrote to guide an Anchoress's contemplation. At the bottom of the manuscript's first folio is written '1368', though the manuscript is clearly later than that date, seeming to indicate that its original exemplar was written in 1368. It appears to desire to preserve what would have been the version of the Showing of Love that Julian could have written when she was twenty-five years of age and five years before the seeming 'death-bed' visions of 1373, for it contains none of these. It is written on parchment in a beautiful hand, within rulings on the small folios, and the texts begin with initial capitals in blue with red penwork, that of Julian using the 'O' of the 'Great O Antiphon', said by the Virgin to her yet un-born Child in Advent, 'O Sapientia'. In doing so, Julian's text imitates and recalls the image used by Marguerite Porete, of her Book, The Mirror of Simple Souls, as an engendering within her by God, for which Marguerite's book had first been burned at Valenciennes by the Bishop of Cambrai in her presence, and then Marguerite herself, condemned by twenty-one doctors of theology, including Victorines, Augustinians, Cistercians, Benedictines, and Franciscans, of the University of Paris, was burned at the stake in 1310. The Amherst Manuscript with Julian's Short Text Showing of Love gives the complete text of Marguerite Porete's Mirror of Simple Souls, translated into Middle English at its folios 137-225, anonymously.

Syon Abbey had to go into exile under first Henry VIII, then again under Elizabeth I. At the Dissolution some of its nuns were forced to marry. On the final folio of the Westminster Manuscript are pen trials giving the names of members of the Lowe family, who also had owned a Syon Abbey Psalter now in Edinburgh in which the birth of a daughter, 'Elinor Mounse Lowe', is recorded on the Feast of the Holy Innocents' Vigil, with a prayer that God make her a good woman. Syon Abbey was first in exile in the Low Countries, then at Rouen, finally making its way to Lisbon. There, Sister Rose Lowe saved the community from extinction and it was possibly she who gave this manuscript to Bishop James Bramston, who had studied theology at the English College in Lisbon, in 1821, for it has his bookplate and his annotations concerning the manuscript's age, and was rebound at that time with the date '1368' stamped on the spine.

The Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Anglais 40, Manuscript /P/

Today this is the only known manuscript of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love that is still outside of England. Of her manuscripts all had once been abroad in exile, with the single exception of the Amherst Manuscript /A/. The Paris Manuscript gives the complete Long Text of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love written out circa 1580 on Flemish paper by a Brigittine nun in exile there. It is copying a now-lost Tudor manuscript prepared for printing by Syon Abbey just prior to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The majority of Julian manuscripts present Christ's words to her in larger letters than the rest of the text, copying the practice one sees in Adam Easton's manuscript in Hebrew of Rabbi David Kimhi's Sepher Miklol. But this would have been a printer's headache, and here the scribe uses, instead, rubrication of the chapter headings, the paragraph signs and Christ's words to Julian. This translation replicates these from /P/.

Syon Abbey went into exile twice, first under Henry VIII, then under Elizabeth I. During the second exile, the poverty of the nuns became so great that they sent several of the younger Sisters in disguise back to England to raise funds and to seek to have books printed for the English Mission, one of these being Walter Hilton's Ladder of Perfection and another, perhaps, Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love. These Sisters braved imprisonment and death. Under Henry VIII several Syon Sisters had continued to live their life of contemplative prayer in the house of a member of one of their families, the damp, moated Lyford Grange. These Sisters returned there, then fled when several of the Recusants were imprisoned from the Grange, including members of the Lowe family which owned /W/. Several had already died in Reading Prison. One Sister, Elizabeth Saunders, was captured, and her books with her, at Alton and inquisitioned by the Anglican Bishop of Winchester, who then imprisoned her in Winchester Castle, seizing the 'certaine lewde and forbidden bokes' from her, likely the Tudor exemplar of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love among them. Another Sister, Marie Champney, died of tuberculosis in London, on her deathbed seeking the printing of books, including Walter Hilton's Ladder of Perfection.

While these Sisters were in England, Syon Abbey

itself moved from the dangers of the Low Countries to similar

dangers in Rouen, France, eventually making their way from

there to Lisbon in Portugal by ship with their possessions in

five crates and a cask. They brought with them the marble

gatepost of Syon Abbey, sculpted with the Instruments of the

Passion, on which part of St Richard Reynolds's quartered body

had been exposed. Which they have still, now in their chapel

in Devon.

Syon Abbey Gatepost with Instruments

of the Passion

Syon Abbey Gatepost with Instruments

of the Passion

But they had to leave behind this Manuscript of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love. It instead entered the great library of the Bigot family in Rouen, which was eventually purchased for the King's Library in Paris, arriving there too late for consultation by Serenus Cressy for his 1670 edition of the Revelations of Divine Love. He must have used either this manuscript's Tudor exemplar or its Elizabethan twin copy.

The British Library Sloane Manuscripts 3701 and 2499 /S/

There are two further manuscripts of the Long Text of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love. The first of these, Sloane 3701, was copied out from a now lost exemplar written, likely, in the hand of Julian herself, and which was in her Norwich dialect, the copy being made at Cambrai, circa 1650, on Flemish paper by English Benedictine nuns in exile there. Sloane 3701 modernizes the text. The English Benedictines at Cambrai had had Dom Augustine Baker, O.S.B., as spiritual director who had encouraged them in their reading and preserving of medieval contemplative texts, such as Walter Hilton and the Cloud Author and Julian of Norwich. Then jealousy arose, the monks desiring to confiscate and prohibit the nuns' now extensive contemplative library. So Cambrai Abbey, in a burst of copying, created an insurance library and even founded a daughter house especially for it, in 1651, sending some of their nuns with these precious copies, at least two, perhaps more, of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love amongst them, to Paris. In that burst of copying, Dame Clementia Cary returned to the exemplar for Sloane 3701 and now exactly copied its medieval dialect, preserving its forms. In the seventeenth century, she was meticulously editing a fourteenth-century work. Her manuscript is the hastily-written Sloane 2499. Her ecstatic comments, made during her initial reading of the text, are found in the margins of Sloane 3701, which clearly preceeded Sloane 2499 also in the dating of its watermarks. Dom Serenus Cressy, O.S.B., the chaplain to the Paris daughter house, then had printed the first edition of Julian of Norwich's Revelations of Divine Love, in 1670, using as base text the twin or exemplar of /P/, and giving marginal collations derived from these fine /S/ manuscripts.

The /S/ manuscripts differ from /P/ in having chapter headings, from their wording clearly written by an editor during Julian's lifetime, which /P/ lacks. They also have a colophon which echoes that to the Marguerite Porete, Mirror of Simple Souls, manuscripts in Middle English (of which there are three, one of these being with Julian's Showing of Love in the Amherst Manuscript), and those to the Cloud of Unknowing author's works. Two other Benedictine nuns, Dame Barbara Constable of Cambrai in the Upholland Manuscript /U/ and Dame Bridget More (descendant of Thomas More) of Paris in the Dame Margaret Gascoigne Manuscript /G/ copied out excerpts from Julian's Showing.

The Amherst Manuscript, British Library Additional 37,790 /A/

1st Gent. Our deeds are fetters that we forge ourselvesIn the Long Text Julian states that she yearns to perform her Book differently, as if she rebelled against the pigeonholing of XV Showings and chapters and interminable cross-references and elitist colophons. Already the Paris Manuscript had ignored the editorializing chapter descriptions and colophon. When Julian is seventy, in 1413, she rewrites the text, as the Amherst Manuscript's Short Text, as if witnessing and writing a legal document rather than a theological treatise, now omitting swathes and swathes of her Biblical translation and adaptation into English, while keeping and even expanding on the physical details of the 'death bed' vision, now so very many years before. Under life-threatening constraints she crystallizes her text, her theology. Her scribe, by his dialect, is from Lincolnshire, a Carmelite, and responsible also for other fine manuscripts for women contemplatives. He is the only male scribe of all seven extant Julian of Norwich Showing of Love manuscripts. Like Westminster and Paris, the manuscript uses capitals in blue, ornamented with red quill work, dividing the text into sections which do not correspond to the Long Text's now abandoned structure of XVI Showings. It is these capital letters, rather than numbers, that Julian prefers for her memory system for her manuscripts. Moreover, in Amherst, our earliest surviving manuscript and written, it notes, during Julian's lifetime, another hand than the scribe has restored eye-skipped lines the scribe has omitted. It is a hand that reminds one of that in the Norwich Castle Manuscript, square and Tudor-like though written at the opening of the fifteenth-century, during Julian's liftetime and evocative of the hand of the late Adam Easton. It is possible these two manuscript contain Julian's own hand-writing.

2nd Gent. Ay, truly: but I think it is the world

That brings the iron.George Eliot, Middlemarch

V. On This Translation

ost modern

editions and translations transform a manuscript text into

something new and strange, like seeing a black and white

photograph of what once was in reds and blues and with gold leaf

upon purple, reducing it from its former glory and memorability

into something ordinary and easy to forget. This translation,

based on the definitive edition by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds,

C:P: and Julia Bolton Holloway, published by SISMEL, Edizioni

del Galluzzo, Florence, 2001, ISBN

88-8450-095-8 (which also gives the substantiating

sources for the historical material in this preface), instead

seeks to replicate as far as possible that original glory of

Julian's manuscripts. The rubrication is that in the Paris

Manuscript (a convenient way then to save parchment and now to

save paper and screen space); the pagination is that in the

Sloane Manuscript; the punctuation follows the clues given in

the various manuscripts, as these demonstrate Julian's cadenced

English; Julian, and/or her scribes,

capitalized temporal titles, such as Church (but not its

adjective, holy), King, Lord, etc., but usually not spiritual

ones, 'god, father, brother, maiden, mother'; the

variants are given throughout incorporating all the versions of

Julian's text and using /WSPAGU/ to signify the texts of the Westminster,

Sloane, Paris, Amherst, Gascoigne and Upholland Manuscripts.

Donald Frame once so edited Montaigne's Essays, showing the layers of text and their accretions through time as the Essays went into printing upon printing. Augustine's Confessions and Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape similarly are self-consciously aware of the stages of the author's life enfolded into the author's text. The same may be seen here. Let us hypoithesize that the Westminster Cathedral /W/ Manuscript attempted to show what Julian's original text might have been in 1368, when she was twenty-five, before her 'death bed' vision, that the Sloane /S/ and Paris /P/ Manuscripts give her 1373 vision at thirty as frame to her 1368 theology and as initially written down in 1388-93, when she was fifty, and the Amherst /A/ Manuscript written by a scribe whom she perhaps corrects, in 1413, when she was seventy, in the face of Arundel's draconian censorship which forbade the translating of the Bible into English, forbade theological teaching by the laity, forbade either of these especially by women, her Amherst text nevertheless crystallizing her teaching on prayer for all her even-Christians, men and women both. All three versions importantly include the vision of the hazel nut, of all that is, in Julian's hand and in ours, of the God's city in Julian's and our soul, and of her desire to die young to be soon with God, as the heart of Julian's contemplation. Jesus as Mother is in Westminster, Sloane and Paris /WSP/ but censored from Amherst /A/. The Lord and the Servant Parable, possibly allegorically about Benedictine Cardinal Adam Easton's torture and dungeon imprisonment by Pope Urban VI, is only present in the Sloane and Paris /SP/ Long Texts. The 'death bed' vision of 1373 is given in Sloane, Paris and Amherst /SPA/, in this last being given greater detail, as if for a witnessed legal document, justifying her writing in the face of Arundel's death-dealing censorship.

To these collations are also added the fragments written out in Cambrai in the Margaret Gascoigne/Bridget More Manuscript /G/ and the Barbara Constable Upholland Manuscript /U/. The letters /M/ and /N/ refer to passages found also in the Book of Margery Kempe Manuscript and the Norwich Castle Manuscript.

I have sought in this translation to remain as faithful to Julian's English as is possible. Both T.S. Eliot and Thomas Merton have highly praised her writing. The manuscripts represent different dialects, Sloane being that of Julian's own Norwich, Amherst that of the neighbouring Lincoln, Westminster and Paris being the London dialect. I have regularized these to modern standard English. Grammar has shifted between her day and ours. Verbs and their agreement with nouns in Julian's text can differ from our practices. The eighteenth century, on the model of Logic, abolished the double negative as positive, requiring either one or the other, but not both. Consequently these are pruned to modern usage. In order to preserve the nature of Julian's original text, words are translated usually into modern equivalents where they are no longer current coin, but sometimes the original word is employed to teach us what it was. We have one word for 'truly', while Julian has three, 'sothly, verily, truly'. Usually, I give our modern word, 'truly', but at times I employ her medieval words. I have retained her 'holy Ghost' and 'ghostly' for 'Spirit' and 'spiritual'. Her admiring male editor, who writes the Table of Contents, the chapter headings and the elitist colophon, likes Latin words, such as 'Revelations', while Julian prefers Anglo-Saxon ones, like 'Showing'. The manuscripts give 'blissful, blessedful' as interchangeable one with the other.

This list gives words this translation sometimes changes, sometimes retains: abide=wait, stay; anon=soon; as farforth=as much as; Asseth=satisfaction, reparation, assay; attemyd=humbled; avisement, attention; be=by; behove= need; beseek=pray, beseech; bliss=bless; bolned=swollen; buxom=pliant, obedient, humble; cheer=expression, mood; creature=a being created by God; demed=judged; depart=separate; example=parable; full=most; Ghost=Spirit; grevid=pregnant; hende=gracious; homely=friendly, familiar; kind=nature; largesse=generosity; learning=teaching; leve=believe (similar to Middle English words for leave and live); let=stop, hinder; like=please, delight; meddled=mixed; mede=reward; mind=think, contemplate, memory; nought=nothing; onde=wind, breath; one=unite; particular=special; privy=secret; reward=regard; rood=cross, securely=surely; Showing=Revelation, skillful=expert, wise; sothly=truly, speed=help, assist, benefit; stint=cease, stop; suffer=allow, permit; swemful=grief; swithe=sudden; that=who; the, thou=you; Uprising=Resurrection; verily=truly, wax=grow; wele=weal, wellness, well being; wened=believed, thought; willfully=willingly; wist=knew; wonyng=home, dwelling; worship=honour, reverence; wroth=to be angry, wrathful.

Though this glossary alphabetically ends with that

word, Julian tells us that in God there is no wrath. Yet her Showing

of Love elicited much wrath and was censored and hidden

for centuries. In her writing she seeks to reconcile the

theologies of Easton and Wyclif; today she would seek to

reconcile men and women, Ireland and England, Rome and

Canterbury, Judaism and Christianity. We need her Apocalypse,

her Revelation, her Showing of Love, more than ever.

Reading her words, let us give thanks for the centuries of

women and men in exile, in prison, awaiting execution, from

burning at the stake, drawing, hanging and quartering, and

guillotining, who, in prayer to God, preserved the Showing

of Love for us. A story of courage and consolation.

Reminding us that God is Father and Mother both, of Might, of

Wisdom, of Love, cherishing and nourishing all, despising

nothing he has made. That he is in smallness as in greatness,

in women as in men, in children as in the grown, in seeds and

their genetic codes, in atoms and their molecular structures,

present as the sacred ABC in all things, 'that all manner of

thing shall be well'. For this Showing of Love you now

have is her Book and his Book, mirroring Eve (whom Julian

never names), and Adam, Mary and Jesus, in whom we all are.

St Agnes' Feast

Florence, 2002

Indices to

Umiltà Website's Essays on Julian:

Preface

Influences

on Julian

Her

Self

Her

Contemporaries

Her

Manuscript Texts ♫ with recorded readings of them

About

Her Manuscript Texts

After

Julian, Her Editors

Julian

in our Day

Publications related to Julian:

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

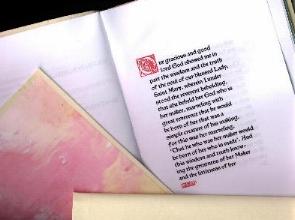

To see an example of a page inside with

parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants

and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a page inside with

parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants

and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway.

Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click

on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search

box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi

8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see

inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's

in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

To see

inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's

in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of

Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton

Holloway. Collegeville:

Liturgical Press;

London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon

ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

To view sample copies, actual

size, click here.

'Colections'

by an English Nun in Exile: Bibliothèque Mazarine 1202.

Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta

Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le

Blévec. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of

Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualität

Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und

Amerikanistik Universität Salzburg, 2008. ISBN

978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A

Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface,

Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10:

0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan

Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Thee: Divine Love in Julian

of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon,

2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among

the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59

Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13)

978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of

Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di

Maria:Antologie di

Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.

Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo

Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta

Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualität Heute und Gestern.

Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik

Universität Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix

+ 484 pp.

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione:'s

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |

JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE

AND ITS CONTEXTS ©1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY

|| JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF

LOVE || HER TEXTS ||

HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN

|| BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER|| CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS

) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY || © Liturgical Press, U.S.A.,

Darton, Longman and Todd, U.K.