Tunc vero Antonius pro foribus corruens, usque ad sextam et eo amplius horam aditum precabatur dicens: Qui sim, unde, cur venerim, nosti. Scio me non mereri conspectum tuum, tamen nisi videro, non recedam. Qui bestias sucipis, hominem cur repellis? Quaesivi et inveni, pulso ut aperiatur. Quod si non impetro, hic, hic moriar ante postes tuos. Certe sepelies vel cadaver. Talia perstabat memorans. fixusque manebat. Ad quem responsum paucis ita reddidit heros: Nemo sic petit ut minetur, nemo cum lacrimis calumniam fecit. Et miraris si non recipiam, cum moriturus adveneris? Sic adridens patefecit ingressum. Quo apertop dum in mutuos miscentur amplexus, propriis se salutavere nominibus: gratiae Domino in comune referuntur.

Et post sanctum osculum residens Paulus cum Antonio ita exorsus est: En quem tanto labore quaesisti, putridis senectute membris operit inculta canities. En vides hominem, pulverem mox futurum. Verum quia charitas omnia sustentat, narra mihi, quaeso, quomodo habeat humanum genus. An in antiquis urbibus nova tecta consurgant; quo mundus regatur imperio; an supersint aliqui, qui daemonum errore rapiantur. Inter has sermocinationes suspiciunt alitem corvum in ramo arboris consedisse, qui inde leniter subvolabat et integrum panem ante ora mirantium ora deposuit; post ejus abscessum: Eia, inquit Paulus, Dominus nobis prandium misit, vere pius, vere misericors. Sexaginta jam anni sunt quod dimidii semper panis fragmentum accipio, verum ad adventum tuum, militibus suis Christus duplicavit annonam.

Igitur in Deum gratiarum actione celebrata super vitrei marginem fontis uterque consedit. Hic vero, quis frangeret panem, oborta contentio, pene diem duxit in vesperam. Paulus more cogebat hospitii, Antonius jure refellebat aetatis.

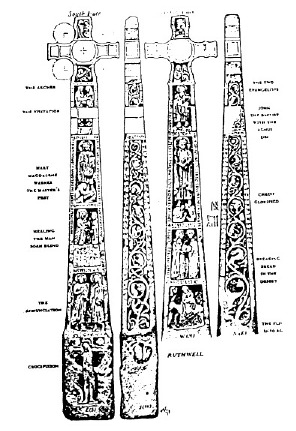

Ruthwell

Cross, Scotland

Ruthwell

Cross, ScotlandAnthony and Paul are breaking bread in the third face, second from the bottom, which is the Flight into Egypt, and below Christ in the Desert.

Tandem consilium fuit, ut apprehenso e regione pane, dum ad se quisque nititur, pars sua remaneret in manibus. Dehinc paululum aquae in fonte prono ore libarerunt, et immolantes Deo sacrificium laudis noctem transegere vigiliis. Cumque iam esset terrae redditus dies, beatus Paulus ad Antonium sic locutus est: Olim te, frater, in istis regionibus habitare sciebam, olim te conservum meum mihi promiserat Deus; sed quia jam dormitionis meae tempus advenit, et quod semper cupiebam dissolvi, et esse cum Christo, peracto cursu superest mihi corona justitiae; tu missus es a Domino, qui humo corpusculum meum tegas, immo terram terrae reddas.

His Antonius auditis flens et gemens, ne se desereret atque ut comitem talis itineris acciperet, precabatur. Ac ille: Non debes, inquit, quaerere quae tua sunt, sed quae aliena. Expedit quidem tibi sarcina carnis abiecta Agnum sequi. Sed et caeteris expedit fratribus, ut tuo adhuc instituantur exemplo. Quamobrem, perge, quaeso, nisi molestum est, et pallium quod tibi Athanasius episcopus dedit, ad obvoluendum corpusculum meum defer. Hoc autem Paulus rogavit non quod magnopere curaret, utrum tectum putresceret cadaver an nudum (quippe qui tanti temporis spatio contextis palmarum foliis vestiebatur), sed ut a se recedenti moeror suae mortis levaretur. Stupefactus ergo Antonius, quod de Athanasio et pallio eius audierat, quasi Christum in Paulo videns et in pectore eius Deum venerans ultra respondere nihi ausus est, sed cum silentio lacrimans exosculis eius oculis manibusque ad monasterium, quod postea a Saracenis occupatum est, regrediebatur. Neque vero gressus sequebantur animum, sed cum corpus inane ieiuniis seniles etiam anni frangerent, animo vincebat aetatem.

Tandem defatigatus et anhelus ad habitaculum suum confecto itinere pervenit. Cui cum duo discipuli, qui et iam longaevo ministrare coeperant, occurrissent dicentes: Ubi tamdiu moratus es, pater?, respondit: 'Vae mihi peccatori, qui falsum monachi nomen fero. Vidi Eliam, vidi Ioannem in deserto, et vere in paradiso Paulum vidi. Ac sic ore compresso et manu verberans pectus ex cella pallium protulit. Rogantibusque discipulis ut plenius quidnam rei esset exponeret ait: Tempus tacendi et tempus loquendi.

Tunc egressus foras et ne modicum quidem cibi sumens per viam qua venerat regrediebatur, illum sitiens, illum videre desiderans, illum oculis ac mente complectens. Timebat enim, quod et evenit, ne se absente debitum Christo spiritum redderet. Cumque jam dies inluxisset alia et trium horarum spatio iter remaneret, vidit inter angelorum catervas, inter prophetarum et apostolorum choros, niveo Paulum candore fulgentem in sublime conscendere. Et statim in faciem suam procidens sabulum capiti superiacierbat, plorans atque eiulans: Cur me, Paule, dimittis? Cur abis insalutatus? Tam tarde notus tam cibo recedis?

Referebat postea beatus Antonius tanta se velocitate quod reliquam erat viae concurrisse, ut ad instar avis pervolaret. Nec immerito, nam introgressus speluncam videt genibus complicatis, erecta cervice, extensisque in altum manibus corpus exanime. Ac primo et ipse vivere eum credens pariter orabat. Postquam vero nulla, ut solebat, suspiria precantis audivit, in flebile osculum ruens intellexit quod etiam cadaver sancti Deum, cui omnia vivunt, officio gestus precaretur.

Igitur obvoluto et prolato foras corpore, psalmis quoque ex Christiana traditione cantatis, contristabatur Antonius quod sarculum, quo terram foderet, non habebat, fluctuans vario mentis aestu et secum multa reputans: Si ad monasterium revertar, quatridui iter es; si hic maneam, nihil ultra proficiam. Moriar ergo, ut dignum est, et iuxta bellatorem tuum, Christe, ruens extremum halitum fundam. Talia eo animo voluente ecce duo leonies ex interioris eremi parte currentes volantibus per colla iubis ferebantur. Quibus aspectis primo exhorruit. Rursusque ad Deum mentem referens, quasi columbas videret, mansit intrepidus. Et illi quidem directo cursu ad cadaver beati senis substiterunt, adulantibusque caudis circa eius pedes accubuere, fremitu ingenti rugientes, prorsus ut intellegeres eos plangere quo modo poterant. Deinde haud procul coeperunt humum pedibus scalpere, harenamque certatim egerentes unius hominis capacem locum effodere. Ac statim quasi mercedem pro opere postulaturi, cum motu aurium cervice dejecta ad Antonium perrexerunt, manus eius pedesque lingentes, ut ille animavertit benedictionam eos a se deprecari. Nec mora, et in laudationem Christi effusus, quod muta quoque animalia Deum esse sentirent, ait: Domine, sine cuius nutu nec folium arboris defluit nec unus passerum ad terram cadit, da illis sicut tu scis. Et manu annuens eis ut abirent imperavit. Cumque illu recessissent, sancti corporis onere seniles curvavit humeros, et deposito eo effossam desuper humum congregans tumulum ex more conposuit. Postquan autem dies inluxerat alia, ne quid pius heres ex intestati bonis non possideret, tunicam sibi eius vindicavit, quam in sportarum modum de palmae foliis ipse sibi texuerat. Ac sic ad monasterium reversus discipulis ex ordine cuncta replicavit; diebusque solemnibus Paschae vel Pentecostes semper Pauli tunica vestitus est.

Libet in fine opusculi interrogate eos, qui patrimonia sua ingorant, qui domos marmoribus vestiunt, qui uno lino villarum insuunt pretia: huic seni nudo quid umquam defuit? Vos gemma bibitis, ille concavis manibus naturae satisfecit. Vos in tunicis aurum texitis, ille ne vilissimi quidem mancipii vestri indumentum habuit. Sed e contrario illi pauperculo paradisus patet, vos auratos gehenna suscipiet. Ille Christi vestem, nudus licet, servavit; vos vestiti sericis indumentum Christi perdidistis. Paulus vilissimo pulvere coopertus iacet resurrecturus in gloriam, vos operosa saxis sepulcra premunt cum vestris opibus arsuros.

. . .

Obsecro, quicumque haec legis, ut Hieronymi peccatoris memineris; cui si Dominus optionem daret, multo magis eligeret tunicam Pauli cum meritis ejus, quam regum purpuras cum poenis suis.

HERE is a great deal of uncertainty

abroad as to which monk it was who first came to live in

the desert. Some, questing back to a remoter age, would

trace the beginnings from the Blessed Elias and from

John: yet of these Elias seems to us to have been rather

a prophet than a monk: and John to have begun to

prophesy before ever he was born. Some on the other hand

(and these have the crowd with them) insist that Antony

was the founder of this way of living, which in one

sense is ture: not so much that he was before all

others, as that it was by him their passion was wakened.

Yet Amathas, who buried the body of his master, and

Macarius, both of them Antony's discip0les, now affirm

that a certain Paul of Thebes was the first to enter on

the road. This is my own judgment, not so much from the

facts as from conviction. Some tattle this and that, as

the fancy takes them, a man in an underground cavern

with hair to his heels, and the like fantastic

inventions which it were idle to track down. A lie that

is impudent needs no refuting.

HERE is a great deal of uncertainty

abroad as to which monk it was who first came to live in

the desert. Some, questing back to a remoter age, would

trace the beginnings from the Blessed Elias and from

John: yet of these Elias seems to us to have been rather

a prophet than a monk: and John to have begun to

prophesy before ever he was born. Some on the other hand

(and these have the crowd with them) insist that Antony

was the founder of this way of living, which in one

sense is ture: not so much that he was before all

others, as that it was by him their passion was wakened.

Yet Amathas, who buried the body of his master, and

Macarius, both of them Antony's discip0les, now affirm

that a certain Paul of Thebes was the first to enter on

the road. This is my own judgment, not so much from the

facts as from conviction. Some tattle this and that, as

the fancy takes them, a man in an underground cavern

with hair to his heels, and the like fantastic

inventions which it were idle to track down. A lie that

is impudent needs no refuting.So then, sincere there is a full tradition as regards Antony, both in the Greek and Roman tongue, I have determined to write a little of Paul's beginning and his end; rather because the story has been passed over, than confident of any talent of mine. But what was his manner of life in middle age, or what wiles of Satan he resisted, has been discovered to none of mankind.

THE LIFE

During the reign of Decius and Valerian, the persecutors, about the time when Cornelius at Rome, Cyprian at Carthage, spilt their glorious blood, a fierce tempest made havoc of many churches in Egypt and the Thebaid. It was the Christian's prayer in those days that he might, for Christ's sake, die by the sword. But their crafty enemy sought out torments wheren death came slowly: desiring rather to slaughter the soul than the body. And as Cyprian wrote, who was himself to suffer: They long for death, and dying is denied them . . .

Now at this very time, while such deeds as these were being done, the death of both parents left Paul heir to great wealth in the lower Thebaid: his sister was already married. He was then about fifteen years of age, excellently versed alike in Greek and Egyptia letters, of a gentle spirit, and a strong lover of God. When the storm of persecution began its thunder, he betook himself to a farm in the country, for the sake of its remoteness and secrecy. But 'What wilt thou not drive mortal hearts to do, / O thou dread thirst for gold?' His sister's husband began to meditate the betrayal of the lad whom it was his duty to conceal. Neither the tears of his wife, nor the bond of blood, nor God looking down upon it all from on high, could call him back from the crime, spurred on by a cruelty that seemed to ape religion.

The boy, far-sioghted as he was, had the wit to discern it, and took flight to the mountains, there to wait while the persecution ran its course. What had been his necessity became his free choice. Little by little he made his way, sometimes turning back and again returning, till at length he came upon a rocky mountain, and at its foot, at no great distance, a huge cave, its mouth closed by a stone. Thre is a thirst in men to pry into the unknown: he moved the sone, and eagerly exploring came within on a spacious courtyard open to the sky, roofed by the wide-spreading branches of an ancient palm, and with a spring of clear shining water: a stream ran hasting from it and was soon drunk again, through a narrow opening, by the same earth that had given its waters birth. There were, moreover, not a few dwelling-places in that hollow mountain, where one might see chisels and anvils and hammers for the minting of coin. Egyptian records declare that the place was a mint for coining false money, at the time that Antony was joined to Cleopatra.

So then, in this beloved habitation, offered to him as it were by God himself, he lived his life through in prayer and solitutude: the palm-tree provided him with food and clothing. And lest this should seem impossible to any, I call Jesus to witness and His holyt angles, that I myself, in that part of the desert which marches with Syria and the Saracens, have seen monks, one of whom lived a recluse for thirty years, on barley bread and muddy water; another in an ancient well (which in the heathen speach of Syria is called a quba) kept himself in life on five dry figs a day. These things will seem incredible to those who believe not that all things are possible to him that believeth.

But to return to that place from which I have wandered; for a hundred and thirteen years the Blessed Paul lived the life of heaven upon earth, while in another part of the desert Antony abode, an old man of ninety years. And as Antony himself would tell, there came suddenly into his mind the thought that no better monk than he had his dwelling in the desert. But as he lay quiet that night it was revealed to him that there was deep in the desert another better by far than he, and that he must make haste to visit him. And straightway as day was breaking the venerable old man set out, supporting his feeble limbs on his staff, to go he knew not whither. And now came burning noon, the scorching sun overhead, yet would he no flinch from the journey begun, saying 'I believe in my God that He will shew me His servant as he said'. Hardly had he spoken when he espied a man that was part horse, whom the imagination of the poets has called the Hippocentaur. At sight of him the saint di arm his forehead with the holy sign. 'Ho there', said he, 'in what part of the country hath this servant of God his abode?' The creature gnashed out some kind of barbarous speech, and rather grinding his words than speaking them, sought with his bristling jaws to utter as gentle discourse as might be: holding out his right hand he pointed out the way, and so made swiftly off across the open plains and vanished from the saint's wondering eyes. And indeed whether the devil had assumed this shape to terrify him, or whether (as might well be) the desert that breeds monstrous beasts begat this creature also, we have no certain knowledge.

So then Antony, in great amaze and turning over in his mind the thing that he had seen, continued on his way. Nor was it long till in a rocky valley he saw a dwarfish figure of no great size, its nostrils joined together, and its forehead bristling with horns: the lower part of its body ended in goat's feet. Unshaken by the sight, Antony, like a good soldier, caught up the shield of faith and the buckler of hope. The creature thus described, however, made to offer him dates as tokens of peace: and perceiving this, Antony hastened his set, and asking him who he might be, had this reply: 'Mortal am I, and one of the dwellers in the desert, whom the heathen worship, astray in diverse error, calling us Fauns, and Satyrs, and Incubi. I come on an embassy from my tribe. We pray thee that though wouldst entreat for us our common God who did come, we know, for the world's salvation, and His sound hath goen forth over all the earth'. Hearing him speak thus, the old wayfarer let his tears run down, tears that sprang from the mighty joy that was in his heart. For he rejoiced for Christ's glory and the fall of Satan: marvelling that he could understand his discourse, and striking the ground with his staff, 'Woe to thee, Alexandria', he cried, 'who does worship monsters in room of God. Woe to thee harlot city, in whom the demons of all the earth have flowed together. What hast thou now to say? The beasts speak Christ and thou dost worship monsters in room of God'. He had not yet left speaking, when the frisky creature made off as it on wings. And this, lest any hesitation should stir in the incredulous, is maintained by universal witness during the reign of Cosntantius. For a man of this type was brought alive to Alexandria, and was made a great show for the people: and his lifeless corpse was thereafter preserved with salt, lest it should disintegrate in the heat of summer, and brought to Antioch, to be seen by the Emperor.

But to return to my purpose: Antony continued to travel through the region he had entered upon, now gazing at the tracks of wild beasts, and now at the vastness of the broad desert: what he should do, whither he should turn, he knew not. The second day had ebbed to its close: one still remained, if her were not to think that Christ had left him. All night long he spent the darkness in prayer, and in the doubtful light of dawn he saw a she-wolf, panting in a frenzy of thirst, steal into the foot of the mountain. He followed her with his eyes, and coming up to the cave into which she had disappeared, began to peer within: but his curiosity availed him nothing, the darkness repelled his sight. Yet perfect love, as the Scripture saith, casteth out fear: holding his breath and stepping cautiously the wary explorer went in.

Advancing little by little, and often standing still, his ear caught a sound. Afar off, in the dread blindness of the dark he saw a light; hurrying too eagerly, he struck his foot against a stone, and raised a din. At the sound the Blessed Paul shut the door which had been open, and bolted it. Then did Antony fall upon the goround outside the door and beyond it. 'Who I am', he said, 'and whence, and why I have come, thou knowest. I know that I am not worthy to behold thee, nevertheless, unless I see thee, I go not hence. Thou who receivest beasts, why dost thou turn away men? I have sought, and I have found: I knock, that it may be opened to me. But if I prevail not, here shall I die before thy door. Assuredly thou wilt bury my corpse'.

'No man pleads thus, who comes to threaten: no man comes to injure, who comes in tears: and dost thou marvel that I receive thee not, if it is a dying man that comes?' And so jesting, Paul set open the door. And the two embraced each other and greeted one another by their names, and together returned thanks to God. And after the holy kiss, Paul sat down beside Antony, and began to speak. 'Behold him whom thou hast sought with so much labour, a shaggy white head and limbs worn out with age. Behold, thou looked on a man that is soon to be dust. Yet because love endureth all things, tell me, I pray thee, how fares the human race: if new roofs be risen in the ancient cities, whose empire is it that now sways the world; and if any still survive, snared in the error of the demons'.

And as they talked they perceived that a crow had settled on a branch of the tree, and softly flying down deposited a whole loaf before their wondering eyes. And when he had withdrawn, 'Behold', said Paul, 'God hath sent us our dinner, God the merciful, God the compassionate. It is now sixty years since I have had each day a half loaf of bred: but at thy coming, Christ hath doubled His soldiers' rations'. And when they had given thanks to God, they sat down beside the margin of the crystal spring. But now sprang up a contention between them as to who should break the bread, that brought the day wellnigh to evening, Paul insisting on the right of the guest, Antony countering by right of seniority. At length they agreed that each should take hold of the loaf and pull toward himself, and let each take what remained in his hands. Then they drank a little water, holding their mouths to the spring: and offering to God the sacrifice of praise, they passed the night in vigil.

But as day returned to the earth, the Blessed Paul spoke to Antony. 'From old time, my brother, I have known that thou wert a dweller in these parts: from old time God has promised that thou, my fellow-servant, wouldst come to me. But since the time has come for sleeping, and (for I have ever desired to be dissolved and to be with Christ) the race is run, there remainether for me a crown of righteousness; that hast been sent by God to shelter this poor body in the ground, returning earth to earth'.

At this Antony, weeping and groaning, began pleading with him not to leave him but take him with him as a fellow-traveller on that journey.

'Thou must not', sai9d the other, 'seek thine own, but another's good. It were good for thee, the burden of the flesh flung down, to follow the Lamb: but it is good for the other brethren that they should have thine example for their grounding. Wherefore, I pray thee, unless it be too great a trouble, god and bring the cloak which Athanasius the Bishop gave thee, to wrap around my body'. This indeed the blessed Paul asked, not because he much cared whether his dead body should rot covered or naked, for indeed he had been clothed for so long time in woven palm leaves: but he would have Antony far from him, that he might spare him the pain of his dying.

Then Antony, amazed that Paul should have known of Athanasius and the cloak, dared make no answer: it seemed to him that he saw Christ in Paul, and he worshipped God in Paul's heart: silently weeping, he kissed his eyes and his hands, and set out on the return journey to the monastery, the same which in aftertime was captured by the Saracens. His steps indeed could not keep pace with his spirit: yet though length of days had broken a body worn out with fasting, his mind triumphed over his years. Exhausted and panting, he reached his dwelling, the journey ended. Two disciples who of long time had ministered to him, ran to meet him, saying, 'Where hast thou so long tarried, Master?'

'Woe is me', he made answer, 'that do falsely bear the name of monk. I have seen Elias, I have seen John in the desert, yea, I have seen Paul in paradise'. And so, with tight-pressed lips and his hand beating his breast, he carried the cloak from his cell. To his disciples eager to know more of what was toward, he answered, 'There is a time to speak and there is a time to be silent'. And leaving the house, and not even taking some small provision for the journey, he again took the road by which he had come; athirst for him, longing for the sight of him, eyes and mind intent. For he feared as indeed befell, that in his absence, Paul might have rendered back to Christ the spirit that he owed Him.

And now the second day dawned upon him, and for three hours he had been on the way, which he saw amid a host of angels and amid the companies of prophets and apostles, Paul climbing the steeps of heaven, and shining white as snow. And straightway falling on his face he threw sand upon his head and wept saying: 'Paul, why didst thou send me away? Why dost thou go with no leavetaking? So tardy to be known, art thou so swift to go!'

In aftertime the Blessed Antony would tell how speedily he covered the rest of the road, as it might be a bird flying. Nor was it without cause. Entering the cave, he saw on its bent knees, the head erect and the hands stretched out to heaven, the lifeless body: yet first, thinking he yet lived, he knelt and prayerd beside him. Yet no accustomed sigh of prayer came to him: he kissed him, weeping, and then knew that the dead body of the holy man still knelt and prayed to God, to whom all things live.

So then he wrapped the body round and carried it outside, chanting the hymns and pslams of Christian tradition. But sadness came on Antony, because he had no spade to dig the ground. His mind was shaken, turning this way and that. For if I should go back to the monastery, he said, it is a three days' journey. If I stay here there is no more that I can do. Let me die, therefore, as is meet: and falling beside thy soldier, Christ, let me draw my last breath'.

But even as he pondered, behold two lions came coursing, their manes flying, from the inner desert, and made towards him. At sight of them, he was at first in dread: then, turning his mind to God, he waited undismayed, as though he looked on doves. They came straight to the body of the holy dead, and halted by it, wagging their tails, then couched themselves at his feet,roaring mightily; and Antony well knew they were lamenting him, as best they could. There, going a little way off, they began to scratch up the ground with their paws, vying with one another in throwing up the sand, till they had dug a grave roomy enough for a man: and thereupon, as though to ask for the reward of their work, they came up to Antony, with drooping ears and down-bent heads, licking his hands and his feet. HJe sw that they were begging for his blessing; and pouring out his soul in praise to Christ for that even the dumb beasts feel that there is God, 'Lord', he said, 'without which no leaf lights from the tree, nor a single sparrow falls upion the ground, give unto these even as Thou knowest'.

Then, motioning with his hand, he signed to them to depart. And when they had gone away, he bowed his aged shoulders under the weight of the holy body: and lahying it in the grave, he gathered the earth above it, and made the wonted mound. Another day broke: and then, lest the pious heir should receive non of the goods of the intestate, he claimed for himself the tunic which the saint had woven out of palm-leaves as one weaves baskets. And so returning to the monastery, he told the whole story to his disciples in order as it befell: and on the solemn feasts of Easter and Pentecost, he wore the tunic of Paul.

. . . I pray you, whoever ye be who read this, that ye be mindful of Jerome the sinner: who, if the Lord gave him his choice, would rather have the tunic of Paul with his merits, than the purple of Kings with their thrones.

IV.

ANY

years ago now John Wyatt and Richard McKeon asked me to teach

medieval Latin in their intensive Latin course at the University

of Chicago. A course in which I myself had been a

student of John's at the University of California at Berkeley,

some years before that. To explain the tensions between pagan

Latin and the Christian monasticism which preserving it I

assembled the following texts:

ANY

years ago now John Wyatt and Richard McKeon asked me to teach

medieval Latin in their intensive Latin course at the University

of Chicago. A course in which I myself had been a

student of John's at the University of California at Berkeley,

some years before that. To explain the tensions between pagan

Latin and the Christian monasticism which preserving it I

assembled the following texts: AULUS

autem, cum Athenis eos exspectaret, incitabatur spiritus eius in

ipso videns idololatriae deditam civitatem . . . Quidam autem

Epicurei et Stoci philosophi disserebant cum eo, et quidam

dicebant: Quid vult seminiverbius his dicere? Alii vero: Novorum

daemoniorum videtur adnuntiator esse; quia Iesum et

resurrectionem adnuntiabat eis. Et apprehensum sum ad Areopagum

duxerunt dicentes: Possumus scire quae est haec nova, quae a te

dicitur, doctrina? . . . Stans autem Paulus in medio Areopagi

ait: Viri Athenienses, per omnia quasi superstitiosiores vos

video. Praeteriens enim et videns simulacra vestra, inveni et

aram, in qua scriptum erat: IGNOTO DEO. Quod ergo ingorantes

colitis, hoc ego annuntio vobis. Deus, qui fecit mundum et omnia

quae in eo sunt, hic, caeli et terra cum sit Dominus, non in

manufactis templis habitat, nec manibus humanis colitur indigens

aliquo, cum ipse det omnibus vitam et inspirationem et omnia . .

.In ipso enim vivimus et movemur et sumus; sicut et quidam

vestrorum poetarum dixerunt: 'Ipsius enim et genus sumus.' Genus

ergo cum simus Dei, non debemus aestimare auro aut argento aut

lapidi sculpturae artis et cogitationis hominis divinum esse

simile. Et tempora quidem huius ignorantiae despiciens Deus nunc

adnuntiat hominibus, ut omnes ubique paenitentiam agant . .

.

AULUS

autem, cum Athenis eos exspectaret, incitabatur spiritus eius in

ipso videns idololatriae deditam civitatem . . . Quidam autem

Epicurei et Stoci philosophi disserebant cum eo, et quidam

dicebant: Quid vult seminiverbius his dicere? Alii vero: Novorum

daemoniorum videtur adnuntiator esse; quia Iesum et

resurrectionem adnuntiabat eis. Et apprehensum sum ad Areopagum

duxerunt dicentes: Possumus scire quae est haec nova, quae a te

dicitur, doctrina? . . . Stans autem Paulus in medio Areopagi

ait: Viri Athenienses, per omnia quasi superstitiosiores vos

video. Praeteriens enim et videns simulacra vestra, inveni et

aram, in qua scriptum erat: IGNOTO DEO. Quod ergo ingorantes

colitis, hoc ego annuntio vobis. Deus, qui fecit mundum et omnia

quae in eo sunt, hic, caeli et terra cum sit Dominus, non in

manufactis templis habitat, nec manibus humanis colitur indigens

aliquo, cum ipse det omnibus vitam et inspirationem et omnia . .

.In ipso enim vivimus et movemur et sumus; sicut et quidam

vestrorum poetarum dixerunt: 'Ipsius enim et genus sumus.' Genus

ergo cum simus Dei, non debemus aestimare auro aut argento aut

lapidi sculpturae artis et cogitationis hominis divinum esse

simile. Et tempora quidem huius ignorantiae despiciens Deus nunc

adnuntiat hominibus, ut omnes ubique paenitentiam agant . .

.  ICUT

enim Aegyptii non tantum idola habebant et onera gravia, quae

populos Israhel destestaretur et fugaret, sed etiam vasa atque

ornamenta de auro et argento et vestem, quae ille populus exiens

de Aegypto sibi potius tamquam ad usum meliorem clanculo

vindicavit, non auctoritate propria, sed praecepto dei ipsis

Aegyptiis nescientur commodantibus ea, quibus non bene

utebantur, sic doctrinae omnes gentilium non solum simulata et

superstitiosa figmenta gravesque sarcinas supervacanei laboris

habent, quae unusquisque nostrum duce Christo de societate

gentilium exiens debet abominari atque vitare, sed etiam

liberales disciplinas usui veritatis aptiores et quaedam morum

praecepta utilissima continent deque ipso uno deo colendo

nonnulla vera inveniuntur apud eos, quod eorum tamquam aurum et

argentum, quod non ipsi instituerunt, sed de quibusdam quasi

metallis divinae providentiae, quae ubique infusa est, eruerunt

et, quo perverse atque iniuriose ad obsequia daemonum abutuntur,

cum ab eorum misera societate sese animo separat, debet ab eis

auferre christianus ad usum iustum praedicandi evangeli.

ICUT

enim Aegyptii non tantum idola habebant et onera gravia, quae

populos Israhel destestaretur et fugaret, sed etiam vasa atque

ornamenta de auro et argento et vestem, quae ille populus exiens

de Aegypto sibi potius tamquam ad usum meliorem clanculo

vindicavit, non auctoritate propria, sed praecepto dei ipsis

Aegyptiis nescientur commodantibus ea, quibus non bene

utebantur, sic doctrinae omnes gentilium non solum simulata et

superstitiosa figmenta gravesque sarcinas supervacanei laboris

habent, quae unusquisque nostrum duce Christo de societate

gentilium exiens debet abominari atque vitare, sed etiam

liberales disciplinas usui veritatis aptiores et quaedam morum

praecepta utilissima continent deque ipso uno deo colendo

nonnulla vera inveniuntur apud eos, quod eorum tamquam aurum et

argentum, quod non ipsi instituerunt, sed de quibusdam quasi

metallis divinae providentiae, quae ubique infusa est, eruerunt

et, quo perverse atque iniuriose ad obsequia daemonum abutuntur,

cum ab eorum misera societate sese animo separat, debet ab eis

auferre christianus ad usum iustum praedicandi evangeli. nter

multos saepe dubitatum est, a quo potissimum Monachorum eremus

habitari coepta sit. Quidam enim altius repetentes a beato Elia

et Ioanne principia sumpserunt. Quorum et Elias plus nobis

videtur fuisse quam monachus et Ioannes ante prophetare coepisse

quam natus sit. Alii autem, in quam opinionem omne vulgus

consentit, adserunt Antonium huius propositi caput, quod ex

parte verum est. Non enim tam ipse ante omnes fuit, quam ab eo

omnium incitata sunt studia. Amatas vero et Macarius, discipuli

Antonii, e quibus superior magistri corpus sepeliuit, etiam nunc

adfirmant Paulum quemdam Thebaeum principem rei istius fuisse,

non nominis, quam opinionem nos quoque probamus. Nonnulli et

haec et alia prout voluntas tulit iactitant: subterraneo specu

crinitum calcaneo tenus hominem, et multa quae persequi otiosum

est incredibilia fingentes. Quorum quia impudens mandacium fuit,

ne refellenda quidem sententia videtur. Igitur quia de Antonio

tam Graeco quam Romano stilo diligenter memoriae traditum est,

pauca de Pauli principio et fine scribere disposui, magis quia

res omissa erat quam fretus ingenio. Quomodo autem in media

aetate vixerit aut quas Satanae pertulerit insidias, nulli

hominum compertum habetur.

nter

multos saepe dubitatum est, a quo potissimum Monachorum eremus

habitari coepta sit. Quidam enim altius repetentes a beato Elia

et Ioanne principia sumpserunt. Quorum et Elias plus nobis

videtur fuisse quam monachus et Ioannes ante prophetare coepisse

quam natus sit. Alii autem, in quam opinionem omne vulgus

consentit, adserunt Antonium huius propositi caput, quod ex

parte verum est. Non enim tam ipse ante omnes fuit, quam ab eo

omnium incitata sunt studia. Amatas vero et Macarius, discipuli

Antonii, e quibus superior magistri corpus sepeliuit, etiam nunc

adfirmant Paulum quemdam Thebaeum principem rei istius fuisse,

non nominis, quam opinionem nos quoque probamus. Nonnulli et

haec et alia prout voluntas tulit iactitant: subterraneo specu

crinitum calcaneo tenus hominem, et multa quae persequi otiosum

est incredibilia fingentes. Quorum quia impudens mandacium fuit,

ne refellenda quidem sententia videtur. Igitur quia de Antonio

tam Graeco quam Romano stilo diligenter memoriae traditum est,

pauca de Pauli principio et fine scribere disposui, magis quia

res omissa erat quam fretus ingenio. Quomodo autem in media

aetate vixerit aut quas Satanae pertulerit insidias, nulli

hominum compertum habetur.